A Theatrical Note About Burlesque

Introduction

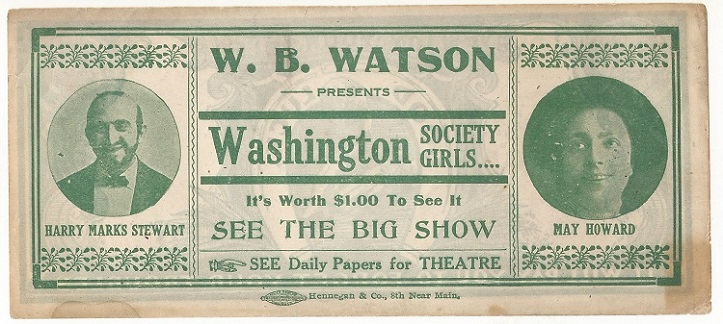

A MAN SAUNTERING down some urban sidewalk in early 20th century America might have been handed this currency-like handbill by a tout loitering outside a theater. Inside, a number of acts were readying for their evening performances. “W. B. Watson presents Washington Society Girls”, with “May Howard” and “Harry Marks Stewart”. “SEE THE BIG SHOW”, exhorts the handbill. Who were these performers? What were their acts, and when did this event take place? Though the handbill itself bears the printer’s imprint of Hennegan & Co., a Cincinnati firm, it could’ve been handed out in any city where these acts were playing. Answering the questions this note raises requires a brief look at a long-defunct form of American popular entertainment, the burlesque show, and at the practitioners whose names and pictures grace this theatrical handbill.

Burlesque in American Culture

In the history of this form of popular American entertainment, burlesque is commonly associated with striptease acts, and with raunchiness in general. While it's true that striptease became increasingly the focus of burlesque shows by the 1920s, arguably this marked the decline of the long-running entertainment form. That said, at the core of the burlesque tradition was always an explicit focus on displays of the female body in sexually-suggestive ways. This feature distinguished burlesque from the broader, more wholesome currents of vaudeville and other, more upscale and respectable forms of theater. Burlesque was always a bawdier and more risqué pastime, one that appealed to a mostly male, working-class audience and which, in the process, periodically provoked the ire of puritanical public authorities.

Histories of burlesque theater date its emergence in the United States to the arrival in 1868, from Great Britain, of Lydia Thompson and her Imported British Blondes. The sensation and controversy that this theater troupe unleashed in New York and elsewhere in the country centered upon the sheer presence of women on stage whose roles and appearance invited the audience to appraise them as sexual beings. Though the performers of the time were fully clothed, by the prevailing standards of middle-class modesty and morality this was in itself a shocking premise. Perhaps even more controversial than the limited amount of flesh the performers displayed was the manner in which the girls behaved. Female performers not only upended gender expectations by playing male roles, but acted in sexually-aggressive ways that scandalized Victorian sensibilities.

Lydia Thompson’s formula was quickly adapted for American audiences by entrepreneurs like M. B. “Mike” Leavitt, creator of the Rentz-Santley Novelty & Burlesque Co. and one of the pioneers of American burlesque. Borrowing from the tradition and structure of American minstrelsy that dated from the 1840s, burlesque quickly evolved into a female-centered performance spectacle that typically contained a number of common elements: a revue of girls, costumed in ways considered racy for the period; musical numbers; short musical farces (“burlettas”) often featuring punning humor and suggestive or ribald dialogue; and any number of comedic or other variety acts. A miscellany of such acts comprised what was called the “olio” portion of a burlesque show.

Borrowing in particular the three-part structure of minstrel shows, burlesque theater quickly adopted a basic formula that, within many versions, became standard after the 1870s. For about forty years until the 1910s, burlesque companies toured the countryside, taking advantage of the rapidly developing national railroad network. As performers developed their acts, managers of burlesque companies combined and recombined them into franchises that, from year to year, offered some variant of the previous season’s shows, using more or less fresh material. Over the years, individual performers with longer careers developed their own reputations, and might tour in any number of shows. As a national entertainment business, by the turn of the 20th century burlesque companies circulated across the country along different circuits, or “Wheels”, each of which were known for different styles and content.

W.B. Watson, The Washington Society Girls, May Howard, Harry Marks Stewart--these were all personalities and acts traveling on burlesque circuits during these years. Newspaper notices and advertisements, particularly those in entertainment publications like Variety and the New York Clipper, report this precise combination of acts together between 1908 and 1910, playing in theatres across the country. At least one or another pair of these featured performers collaborated on burlesque stages for most of the first decade of the century.

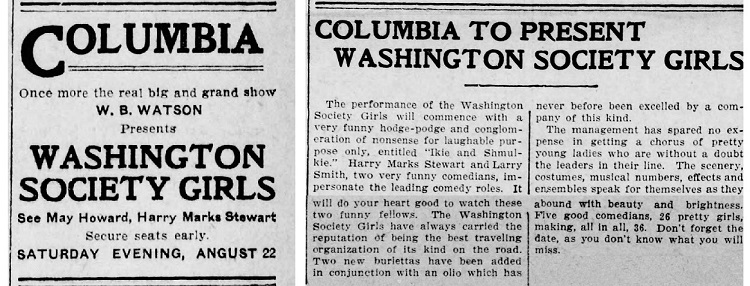

Notices for the Washington Society Girls (The Scranton Republican, August 16 and 21,1908).

W.B. “Billy” Watson

Born Isaac Levie (Levy) on New York’s lower east side, Billy Watson (1866-1945) began as a singer, adopting that moniker in 1881 after taking over for another performer of that name who happened one evening to fall sick. Watson developed his skills as a “Dutch” (from “Deutsch”) comedian, meaning he played thickly-accented, stock Germanic characters to humorous effect. Staples of his comedic repertoire were skits like “Life in Japan” and “Krausemeyer’s Alley” (the spelling varies), the latter becoming a fixture of burlesque and vaudeville shows for decades. In this act, a pair of cantankerous neighbors, played as two stereotypically German and Irish fathers, are at war with each other until a romance between the son of one and the daughter of the other brings about a reconciliation. As he became professionally successful, Watson moved into managing shows like the Washington Society Girls, which he ran with his brother Lew. Ultimately Watson grew wealthy as an investor and theater owner in his own right, retiring as a millionaire.

W.B. Billy "Beef Trust" Watson (New York Public Library)

Of the shows Billy Watson managed, he was perhaps best known for his “Beef Trust.” Created in 1909, this was a troupe of women chosen for their plumpness. The name of course was a tongue-in-cheek reference to the muckraking journalism of Upton Sinclair, whose 1906 exposé The Jungle, describing horrific conditions in the Chicago meatpacking industry, popularized the term Beef Trust to describe its corporate malefactors. Though heavier than even the ample standards of the time, the thirty or so women that made up Billy Watson’s Beef Trust were hardly objects of ridicule. Their spectacle merely exaggerated the prevailing standard of beauty, though with a bluntness that would be unacceptable today. Advertisements for the show (like the poster illustrated here) highlighted the cumulative weight of the performers, and theaters held contests that gave out prizes to the patrons who came closest to guessing what that collective weight was.

"Beef Trust" poster reprinted from Betz (2015); photo from the Ohio State University.

The Washington Society Girls

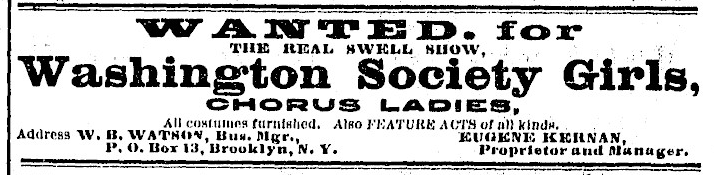

Ironically, of all the acts advertised on this handbill, the central feature of the evening’s entertainment, the Washington Society Girls, is the element about which the least is known. All burlesque shows consisted of revues of girls that went by dozens of different titles, and around which were built the evening’s performances by adding comedy routines, burlettas, and the variety routines that made up the olio. Seldom however, were the individual chorus girls identified by their names unless circumstances and talent enabled them to break out into their own careers. In the mass, their cumulative feminine charms represented the central visual element, and audience draw, of the burlesque show. In newspapers of the time, notices of the Washington Society Girls began to appear in August 1905, with Eugene Kernan the proprietor and manager and Billy Watson as their business manager. For the next few years, Kernan & Watson’s company traveled on the Western (also known as the Empire) Wheel, the circuit with the racier reputation. Numbering between 25 and 30, one local newspaper described the performers as “peach blossom girls, bewitching and attractive.”

Advertisement in the entertainment weekly the New York Clipper, July 22 1905.

Although a core element of the burlesque experience, these all-girl shows had a short shelf life and were treated as relatively interchangeable. After four years, by 1909 the trade publication Variety would write about the Washington Society Girls, “the show lacks novelty or freshness, the greater part of the material being used last season, but nonetheless there is plenty to laugh at, even when the comedians are not dealing with double-meaning dialog or suggestive business.” In May 1911, Variety reported that Billy Watson had relinquished control of the Washington Society Girls to another manager (by this time, Watson was also busy with his “Beef Trust”). The show continued to receive notices until the end of 1912, after which the name simply disappeared, after the fate of many other such shows.

May Howard, the “Queen of Burlesque”

Of the three people named on the handbill, May Howard figures most prominently in the history of burlesque. Born Mary Jean Havill in Paris, Ontario, around 1843, Howard escaped an early marriage and moved to Chicago, apparently following her older brother, George B. Havill, (some accounts describe him as her father, or her uncle) who went on to have a colorful criminal career in his own right under the name of Joseph Cook. In Chicago, she appeared on stage by 1868-69 before decamping to New York, where she joined the Rentz-Santley show and quickly developed a standout reputation. By 1888 she established her own, eponymous, company, with her husband, Harry Morris (who had his own career as a comedian).

May Howard, portrait and in full form (University of Washington/ Wikimedia Commons; New York Daily News 1922).

Known as the “Queen of Burlesque” (although there were others), May Howard and her company became one of the leading acts in the business—in her words, “a leg show pure and simple.” Though she had both singing and comedic talent, Howard’s singular stage asset was a voluptuous body that fully expressed the prevailing 19th century standard for feminine pulchritude. Stuffed into corsets and sequined tights, the effect of her body on male audiences was sensational. In the words of playwright and critic Bernard Sobel, “She was a handsome young woman with a figure whose every line was destined to be known to millions of eyes over the footlights and through photographic reproduction.”

Three Theatrical Beauties: Adrienne Ancion, Saharet, and May Howard (New York Clipper 1898)

Like Billy Watson’s “Beef Trust”, May Howard’s act specialized in women of ample proportions. She was famous for declaring that she would hire for her acts no girl who weighed less than 150 pounds. With her divorce and later death of her husband by 1905, Howard continued on her own, late in her career but still big enough of a star to share the billing with W.B. Watson’s Washington Society Girls in 1908. As late as 1914 she was still active in the business, managing a show called “Girls of All Nations.” By 1921 she retired to Chicago.

May Howard's later years are obscure in an intriguing way because of her older brother’s (father’s? uncle’s?) circumstances. Having avoided serious contact with the law in Chicago, George B. Havill had moved east in 1879 to work with, among others, the forger Charles O. Brockway, and honed his criminal skills along those lines. After spending much of the 1880s in jail, Havill returned to Chicago, reuniting with his wife Teresa Kinzig and their daughter Cora; thereafter, Havill transformed himself into a legitimate and successful businessman in real estate and owner of race horses, even naming one of them “Cora Havill.” Apparently May Howard remained in touch with her older sibling. A newspaper report from 1895 noted how she helped her brother avoid criminal prosecution by attesting to his whereabouts, thus giving him an alibi. Moreover, in 1904, May Howard’s Musical Extravaganza Co. playing in Dodge City, Kansas, listed a “Cora Havill” as one of the chorus girls.

May Howard's The Ladies Alimony Club (Library of Congress).

With his death in 1913, George Havill left behind a sizeable estate worth some $325,000 that precipitated a fight between the widow Kinzig and a pair claiming to be Havill’s real son and daughter. While Kinzig won the fight over his estate, the second daughter was reported not only to have given her name as May Howard, but also to have had her own career in theater and film! Thereafter, newspaper references to May Howard tended to blur the identities of these two individuals. For example, in 1935, short obituary notices of the death of the former “queen of burlesque” gave her age as only 65. This cannot be correct, as it implies she would have been still a child at the time she embarked on her burlesque career with Rentz-Santley! Even if this were the right May Howard with only an incorrect age, assuming her birth year (1843) was accurate, this would have made her 92 years old, which simply seems improbable given that she was reported to be active in theater into the 1920s. Some accounts give her year of death as 1925, which seems more likely, yet there seem to be no public notices of that event. Thus remains a little mystery that a real historian of the theater needs to sort out.

Harry Marks Stewart, “Hebrew” Comedian

Less well-known perhaps than Watson or Howard was Henry (“Harry”) Marks Stewart (1870-1943). A comedian who worked the burlesque circuits for most of his career, Stewart did manage in the 1920s to move up into mainstream theater with his role in the romantic comedy “Abie’s Irish Rose”. Though sniffed at by critics, the play was successful enough to have a run in London by the end of the decade.

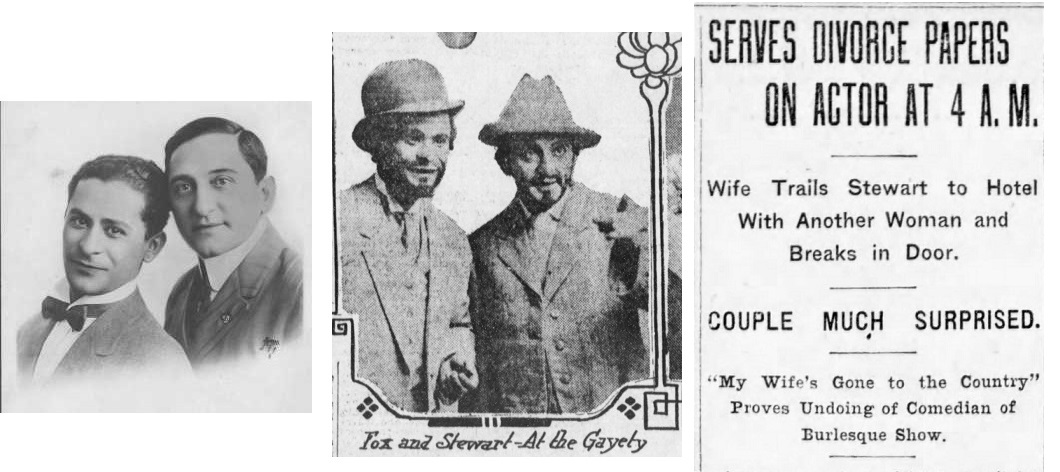

Will Fox (L) and Harry Marks Stewart (R), Al Reeves publicity photo; in costume (the Omaha Bee 1913); caught in the act (Brooklyn Daily Eagle 1910).

In the burlesque formula as it developed by the end of the 19th century, comedy acts like Stewart’s or Watson’s often served as humorous interludes between the larger song-and-dance performances by the female choruses, or contributed to the miscellany that comprised the olio section of the show. Comedy of the time in burlesque and vaudeville typically evoked racial and ethnic stereotypes after the well-established tradition, going back to the 1840s, of blackface minstrelsy. Just as Billy Watson specialized in ethnic German caricatures, Stewart’s own humor exploited Jewish stereotypes--newspapers would refer to performers like Stewart as “Hebrew” comedians—to a degree that got laughs from contemporary audiences but would probably be considered crude and even offensive by present-day standards.

Stewart’s name begins appearing in advertisements and trade publications at the turn of the century. During the second half of that decade he worked off and on with the Washington Society Girls. It was during that period in June 1910 that Stewart, a married man, had the misfortune of being caught in bed with one of the chorus girls. His wife, Mrs. Lulu Stewart, employed a detective to follow the comedian back to his hotel, where she served divorce papers on him in flagrante delicto.

Like Watson, Stewart had a signature ethnic act, “Ikey and Schmulkey”, which he performed year in and year out while traveling with different shows. His most enduring professional association was with another “Hebrew” comedian, Will Fox. For a good part of the decade after working with the Washington Society Girls, Stewart along with Fox played as a comedy team with Al Reeve’s Big Beauty Show, performing in acts like “Playing the Ponies”, “The Gay New Yorkers”, and “Madame Who Are You?” and as the stock ethnic characters Plonsky and Pincus in “The World of Pleasure”. The play "Abie's Irish Rose", which vaulted him into mainstream theatre, was in fact quite derivative of the premise of "Krausemeyer's Alley", the ethnic collision now being between Jews and Irish, rather than Germans (the World War had rendered Germans an unpopular ethnicity in American culture).

The Rise and Fall of Burlesque

According to the cultural historian Robert Allen, burlesque and its distinctive combination of music, humor, and feminine charms reached its high point in American popular culture within a few years of the performances advertised on this handbill. By 1912, some seventy different traveling burlesque companies were performing on one “wheel” or another, appearing in about a hundred different theaters across the country in a given year, mostly in the larger cities of the East and Midwest. As a business, burlesque was roughly a quarter of the size of vaudeville. Burlesque largely avoided the more culturally conservative South. Although as an entertainment form burlesque overlapped with its larger and more respectable vaudeville cousin, burlesque shows tended to play in designated burlesque theaters that catered to a rougher, working-class clientele.

Beginning in the 1920s, the dwindling of burlesque into the less savory niche we remember it by happened for several reasons. First and foremost were the disruptive transformations wrought by the advent of radio and especially movies, both of which contributed to the demise of vaudeville as well. The essence of burlesque was always the exploitation of female sexuality (what was called the “leg business”). This was easiest to pull off when prevailing social standards were stricter and prudish. In the late 19th century, it took little more than women stuffed into flesh-colored tights to get a rise out of an audience. As women’s fashions transitioned out of a Victorian era of layers and bustles, simpler and more revealing clothing styles meant that burlesque had to compete with what men could simply see on an everyday city sidewalk. As one female performer observed in 1895, “when a man can go out in Central Park and see a dozen pairs of well-shaped legs and tight-fitting knickerbockers for nothing, he won’t pay to go to the theater unless he can see a great deal more.”

Changes in the Ideals of female bodily beauty accompanied these shifts in fashion. While the fleshy voluptuousness of May Howard (and especially of the women in Watson’s “Beef Trust”) may have been exaggerated even for their time, a cultural valorization of the slim female form as epitomized by revues like Ziegfeld’s Follies (beginning in 1907) increasingly rendered the burlesque of May Howard’s heyday as obsolete and even grotesque.

As those standards for female display changed and loosened, burlesque had to up its game by incorporating sexually suggestive dance routines into its repertoires. Thus, the “cooch” craze starting in the 1890s (stimulated notably by scandalizing performances at the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893) gave way to the “shimmy” in the 1910s, leading to the beginnings of striptease by the 1920s. As burlesque became more unsparingly focused on the female body, this narrowing of its gaze contributed to the genre’s marginalization as a niche and somewhat disreputable form of entertainment. The culmination and, in some ways, the downfall of this trend came with the rise of the Minsky Brothers, whose New York theaters pushed the envelope on nudity until they were finally shut down by city authorities in 1937.

By this time, though, burlesque had come a long way from the ladies-in-tights titillation of the previous century. Already by 1932, a reviewer in the New York Times claimed that burlesque “has become another musty daguerreotype of a vanished age,” stressing how unfamiliar its original sensibility had become to popular culture:

As the gentle reader gazes appalled at the generous anatomy of burlesque’s belles of another day he must puzzle over the unpredictable changes in man’s conception of feminine beauty. Why these ponderous legs like Pillars of Hercules? Why these massive bosoms like bulwarks supporting great broad shoulders, the blacksmith arms held aggressively akimbo on billowing hips? And all these tremendous foundations surmounted by the strong, sturdy features of good-natured amazons who feared neither man nor devil? Is it not possible that these beautiful belles of burlesque symbolized America’s age of expansion, the generous fruitful proportions of a new country in the making; and, above all, the energetic rôle that women were beginning to play in America—the pioneer woman turned Amazon and beginning to battle men on their own ground? Verily, the rise of the Titaness was surely reflected in burlesque.

..........

REFERENCES

Allen, Robert C., Horrible Prettiness: Burlesque and American Culture (University of North Carolina Press 1991).

Betz, Frederick, “’Krausmeyer’s Alley’: Slapstick Burlesque in Mencken’s Christmas Story” Menckeniana 210 (Summer 2015), pp. 11-19.

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 20, 1910.

Chicago Examiner, January 13, 1916.

Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, NY), March 21, 1895,

Noble, Hollister, “Queens of Burlesque”, New York Times, January 24, 1932.

New York Clipper (various dates).

Professional Criminals of America—REVISED (Revised biographies based on NYPD Chief Thomas Byrnes 1886 book, Professional Criminals of America), #15 Joseph Cook.

https://criminalsrevised.blog/2018/05/08/15-joseph-cook/

St. Louis Globe-Democrat, December 30, 1897.

Sobel, Bernard, A Pictorial History of Burlesque (NY: G.P. Putnam’s Sons 1956), quote p. 45.

The Globe-Republican (Dodge City, KS), April 21, 1904.

The Independent (Kansas City, MO), December 24, 1910.

The Scranton Republican, August 16, 1908,

Toll, Robert C., On With the Show: The First Century of Show Business in America (Oxford University Press 1976), quote p. 225.

Variety, December 4, 1909, p. 31.

Washington Post, September 2, 1906; November 11, 1909.

Zeidman, Irving, The American Burlesque Show (NY: Hawthorn Books, 1967).