Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

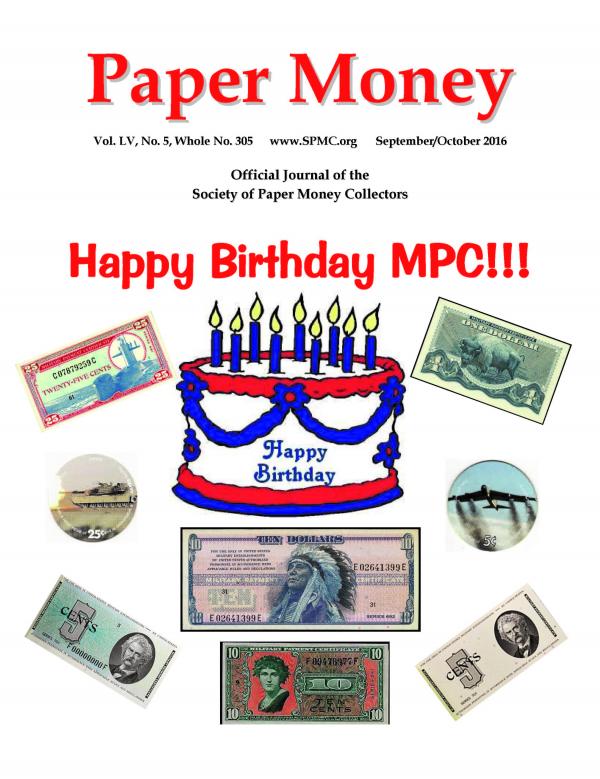

Happy Birthday MPC--Joe Boling & Fred Schwan ............................................ 315

Stack’s Paymaster Auction Report--Fred Schwan............................................. 324

Populations of MPC Known in Collector’s Hands--Carlson Chambliss............. 328

AAFES Pogs--William Myers ............................................................................. 337

Fractional MPC--Benny Bolin ............................................................................. 340

3rd Example of Postage Currency Used as Postage--Rick Melamed ................. 345

Chester Krause ................................................................................................. 346

Post-Date Back Series of 1882 & 1902 NBN--Peter Huntoon ............................ 348

Series of 1886 Silver Dollar Back $5 Silver Certificates--Lee Lofthus ................ 352

Small Notes—Jamie Yakes .............................................................................. 360

Rise & Fall of John Parkman—Charles Derby ................................................... 365

Corp. of Richmond, VA Currency Notes—Josh Kelly ........................................ 381

Isaac Young and the Bank of St. Croix—Shawn Hewitt .................................... 379

Obsolete Corner—Robert Gill .......................................................................... 386

Interesting Mining Notes—David Schenkman ................................................ 388

President’s Message ......................................................................................... 391

Editor Sez .......................................................................................................... 392

Chump Change—Loren Gatch ........................................................................ 393

New Members ................................................................................................... 394