Politics and Paper Money

The Buck Stops Here: Anti-Truman Scrip of 1952

Introduction

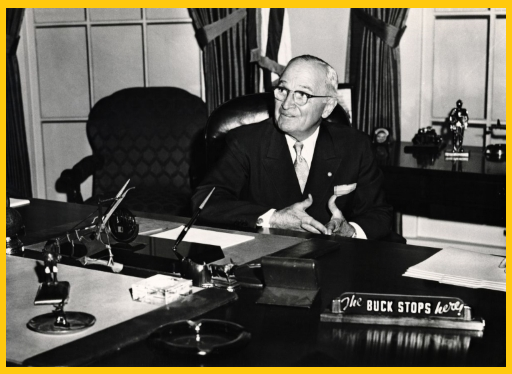

After some seventy-five years, the residues of President Harry S. Truman’s public image include his scrappy, underdog win in the 1948 election against Dewey and his reputation as a bluff and no-nonsense leader, epitomized by the sign that once sat on his Oval Office desk, “The Buck Stops Here.” This later reputation was belied, however, by the circumstances in which Truman left office, and public life, in 1952. Beset by a series of scandals that tarnished his administration after the 1948 election, Truman declined partly for those reasons to run for a second term. Instead, Dwight D. Eisenhower and Richard M. Nixon won a decisive victory over Adlai Stevenson and John Sparkman, returning the Republicans to the White House after a twenty-year absence.

Truman poses with his "The Buck Stops Here" sign at a replica of his White House desk in the Truman Library, 1959 (Image source: Truman Library)

In basic ways, Truman’s Presidency resembled Lyndon B. Johnson’s fifteen years later. As the running mates of more inspirational and charismatic figures, both Truman and Johnson took office after the death of a sitting President. Although vastly different in temperament and personal morals, as political professionals both men were products of their highly transactional political environments—for Truman, the machine politics of Kansas City during the era of boss Tom Pendergast; in Johnson’s case, the corrupt, vote-stealing politics of Texas. As Presidents, both Truman and Johnson incurred the wrath of the Southern wing of the Democratic party by pushing for civil rights measures. Moreover, Truman and Johnson both dealt with wars (Korea, Vietnam) that grew as political liabilities the longer those conflicts lasted. Related to these conflicts was the economic problem of inflation, which became a cudgel that the Republicans wielded both against Truman in 1948 and against Johnson after 1964.

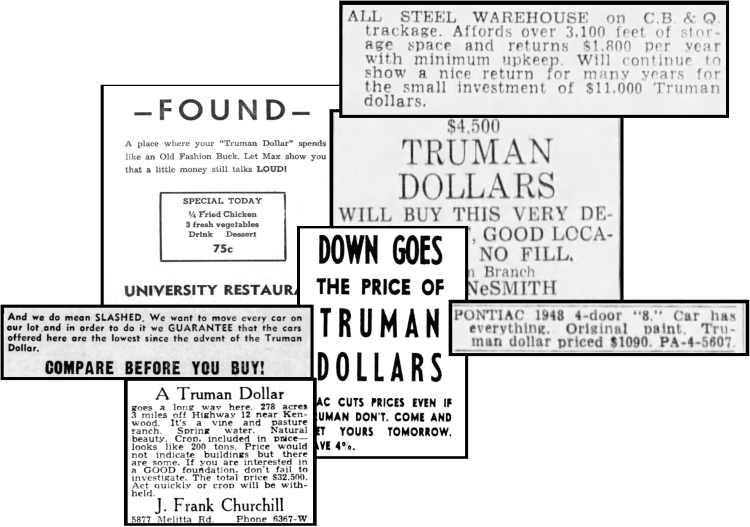

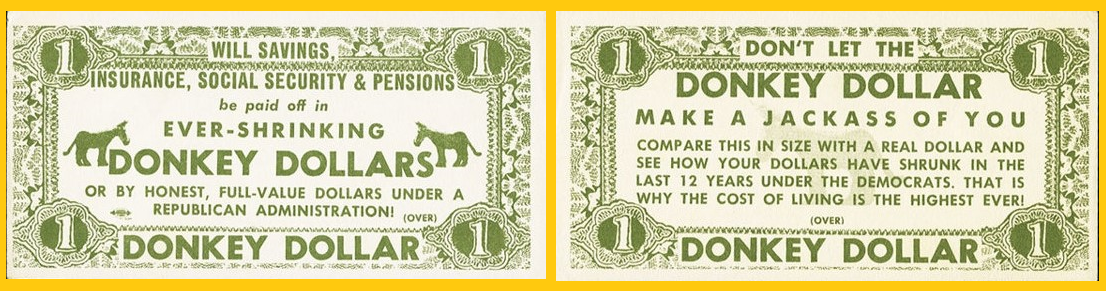

Finally, both Presidents were dogged by accusations of corruption, hardly novel charges in the world of politics. In Johnson's case, his accumulation of ethical baggage long predated his entrance into the White House. For Truman, the problem was more the people who worked under him. Like Johnson fifteen years later, Truman and his ethical travails were the focus of political scrip that made hay of his predicaments. The first two considered here are the “Truman Dollar”, put out in late September 1952 by the Women’s Brigade for Eisenhower, and the “Inflation Certificate” issued earlier that March by two Texans, Jack Fulshear and E. J. Mantooth. By the time both of these pieces were in circulation, Truman had announced his decision not to seek re-election. Instead, the Democrats chose Adlai Stevenson as their candidate at their July convention. Inevitably, though, the record of the Truman Administration became the focus of Republican campaign attacks. In particular, the theme of inflation was stressed by Eisenhower in whistle-stop speeches in which he used as a prop a third example of scrip examined here, the “Donkey Dollar”, to ridicule the Democrats’ handling of prices.

The “Truman Dollar”

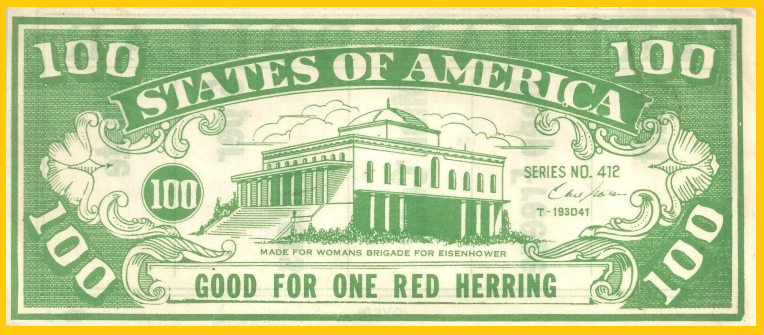

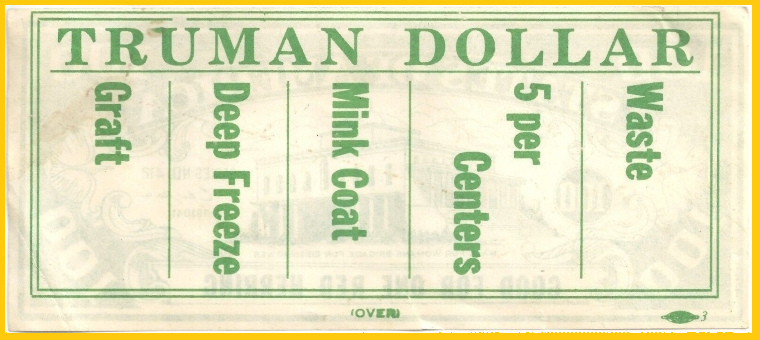

Of the three pieces of scrip, the “Truman Dollar” is the most enigmatic note. The front features a rather ungainly building that may be a rendering of the proposed Truman presidential library. Despite featuring the denomination “100”, the note is labeled “Good for One Red Herring,” a reference to Truman’s dismissive reaction, in 1948, to the House Un-American Activities Committee investigation into communist influence in the government, which he termed a “red herring” meant to distract the American public from congressional inaction on the President’s domestic priorities. Above that are the words, “Made for Womans [sic] Brigade for Eisenhower.”

Front and back of the "Truman Dollar." The series and serial numbers are the same on all examples. The printed signature is unidentified (Image Source: Heritage Auctions).

The Women’s Brigade for Eisenhower and Nixon was formed by a number of Hollywood personalities in late September 1952, just after Richard Nixon delivered his famous “Checkers” speech, which cleared up any uncertainty about him being Eisenhower’s running mate. Led by the redoubtable gossip columnist Hedda Hopper and the MGM executive Ida Koverman, members included other, Republican-leaning, Hollywood figures like Irene Dunne, Lucille Ball, June Allyson, and Sazu Pitts. With not much more than a month to go before the November election, the Women’s brigade threw itself into campaigning for the Republican ticket, mostly by organizing motorcades of convertibles that traveled around to nearby towns in balmy southern California. At each stop, the caravans would perform skits and other bits of theater that highlighted one part or another of the Republicans’ campaign mantra, “Korea, Communism, and Corruption.” Although no newspaper account of these antics specifically mentions use of the “Truman Dollar”, it’s plausible that these slips of paper were dispensed to onlookers in the manner depicted in the picture below.

Antics of the motorcades sponsored by the Women's Brigade for Eisenhower (Image source: Los Angeles Times, October 1, 1952).

Despite suggestions to export the idea of a motorcade campaign to other cities, the Women’s Brigade for “Ike and Dick” remained a local organization that went dormant after the November election but which was revived for the 1956 contest.

On the reverse of the “Truman Dollar” appear three phrases—“5 per Centers”, “Mink Coat”, and “Deep Freeze”—that will be explained below.

Mantooth’s and Fulshear’s “Inflation Certificate”

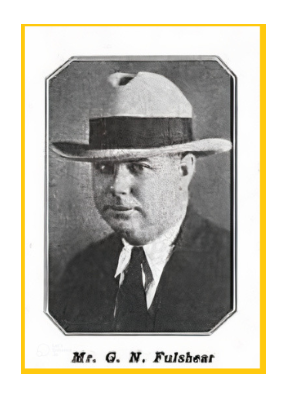

Dating from March of 1952, just around the time that Truman announced his intention not to run, the “Inflation Certificate” made something of a splash when it appeared, attracting newspaper commentary around the country and even some hostile scrutiny from the Secret Service, which objected to its anti-Truman parody of the U.S. dollar. Like their anti-LBJ product the “Bettor Deal Certificate” that would appear twelve years later, Edwin James Mantooth and Graves Nellis (“Jack”) Fulshear affected a yuk-yuk style of satirical humor that piled on reference after reference to Truman Administration peccadillos.

In their overall effect, their notes were quite similar to the novelty currency put out at the time by another Houstonian, Leo Urban “Luke” Kaiser, the owner of Premier Printing. An amateur magician and something of a jokester, Kaiser and his company produced a wide variety of gag money over the years, typically in exaggerated sizes, that made affectionate fun of their topics, notably the State of Texas. Unlike Mantooth and Fulshear, Kaiser steered clear of politics.

Little is known about E. J. Mantooth (1899-1978), other than that he was the nephew of a prominent Texas judge by the same name and spent his career working as a commercial artist for Houston newspapers. Thus, it is likely that Mantooth was responsible for the execution of the notes themselves. Jack Fulshear (1894-1980) began his career in advertising, first managing the art department for O. S. Lammers, a San Antonio concern that sold barber and shaving products. During the 1920s he resided in Austin, where he was on the advertising staff of the Austin Statesman newspaper, before getting involved in a couple of advertising agencies. By the next decade, Fulshear relocated to Houston to work in publicity and sales for the W. C. Munn department store and then later at the Houston Chronicle. Fulshear henceforth remained in that city, setting up his own firm, Direct Mail Services, during the 1940s. At the time he and Mantooth put out their satirical notes, Fulshear was the owner and operator of a printing concern, the Jack Fulshear Co. Of the two men, Fulshear was the one who spoke out publicly about their currency antics. Whenever their notes created controversy, it was always Fulshear who engaged with the press.

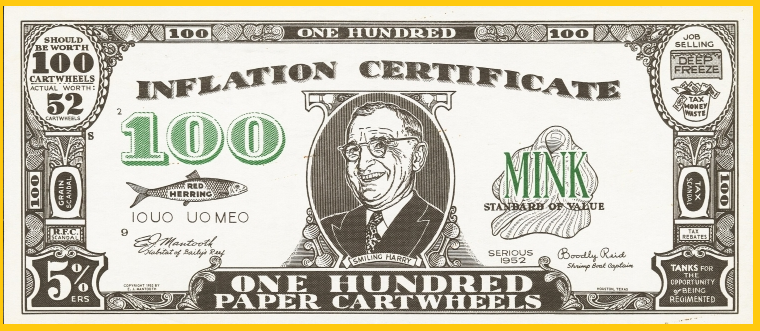

Mantooth’s and Fulshear’s “Inflation Certificate” appeared in two varieties. In the first version, the front features a medallion portrait of an ebullient Harry Truman whose grin comes off as a bit idiotic given the litany of scandals that surrounds him. To the left appears a visual reference to his “red herring” remark; to the right, a mink coat labeled “Mink Standard of Value.” That the note is styled as an “Inflation Certificate” that “should be worth 100 Cartwheels: Actual Worth, 52 Cartwheels” anticipated what would become a refrain of the 1952 campaign, namely that Democratic overspending was responsible for the inflationary debasement of the U.S. dollar, which by then had barely half of the purchase power it did in 1939.

The front of version one of the "Inflation Certificate." Examples of this version do vary slightly, with the signature of "Boodly Reid" replaced with "Jack Fulshear." (Image source: Heritage Auctions).

The first version of the “Inflation Certificate” appeared in late March 1952. It, along with one of Luke Kaiser’s novelty products, came to the attention of the Secret Service, which demanded changes in both notes so as to enhance the differences between them and standard U.S. currency (as if anyone would have ever confused them for the real thing). Kaiser was asked to replace the portrait of Washington on his note, which he obligingly did with one of the Texas founder, Stephen Austin.

The back of the "Inflation Certificate." Between the two versions of the note, this side differs only in the title of the musical score sitting on the piano.

The Mantooth-Fulshear product featured Truman, who of course appeared on no U.S. currency at all. Moreover, measuring nearly ten inches long, it would not have duped even the most careless handler of paper money. Nonetheless, the Secret Service objected to it on the grounds that it represented a “burlesque of the President, and of the currency,” and ordered the two Houstonians to stop printing their certificates. The partisan tone of this objection, and the harsher treatment meted out to them compared to Kaiser, invariably led to cries that Mantooth and Fulshear were being targeted for political reasons.

Just as would happen twelve years later with their “Bettor Deal Certificate”, reports of the government’s disapproval of the parody note appeared in newspapers across the country, creating a golden opportunity which Fulshear, with his advertising nous, was quick to jump on. Declaring his note “too hot for Harry”, Fulshear blustered about taking legal action against the government. By early April the Secret Service relented and “Inflation Certificates” went back into production, which Mantooth and Fulshear advertised and sold through mail-order. At some point Truman himself had apparently responded to the ruckus by labeling their note “Republican eye-wash” (in one press account, Fulshear described himself as a Democrat, albeit of the “Texas brand”). In short order they cranked out a second version of their product that replaced Truman’s portrait with a horseshoe-framed image of a morose donkey, one ear covered with a bandanna, next to a bottle labeled “eye wash.”

The front of version two of the "Inflation Certificate." This was issued after the Secret Service had given permission to resume printing, with changes to the portrait made that reflected President Truman's reported reaction to the first version (Image source: author's collection).

The backs of both versions of the "Inflation Certificate" are almost identical. At the center is an upright piano (Truman’s affection for that instrument was well known). Surrounding that is more, generically anti-big government phrasing.

5 Percenters, Deep Freeze, and Mink Coats

Like the scrip issued by Women’s Brigade for Eisenhower, the front of the Mantooth – Fulshear notes make reference to “5 Percenters,” “Deep Freeze,” and “Mink Coat.” These three elements common to both notes were gestures to scandals that came to light in Truman’s first full term in office:

“5 Percenters” was a slang term used at the time to refer to a certain kind of political operative in Washington D.C. whose connections enabled them to facilitate transactions or otherwise gain favors on behalf of clients, usually private businesses, who were seeking some benefit from the government. Such influence-peddling had become lucrative and, perhaps, unavoidable in a political environment where the vast expansion of government wartime purchasing, along with the imposition of a complicated rationing regime for scarce materiel, created incentives for private interests to engage fixers who, for a fee (a “percentage” of the value of the benefit sought), would use their inside knowledge and personal relationships to advocate for their clients.

The proliferation of so-called “5 Percenters” was widely decried as corruption. Indeed, Truman himself, when he was a Senator, burnished his national reputation after 1941 by chairing an investigative committee that looked into the very same activities in the area of military procurement. As President, however, Truman became vulnerable to the same charge through the conduct of his personal aide, Brigadier General Harry H. Vaughn, who had a habit of using his position to dispense favors to various individuals, including one particularly energetic grifter named John F. Maragon. An investigation undertaken by Senator Clyde R. Hoey (D-NC) in September of 1949 revealed the extent of Vaughn’s mischief over the years. Allegations against Truman’s aide included his efforts to secure scarce construction materials for a California race track and supplies of molasses for a politically-connected vendor. Such seemingly banal gestures took place in an economic context where wartime mobilization had imposed all manner of rationing and restrictions on access to everyday resources. Although Hoey’s subcommittee didn’t find much evidence that Vaughn personally benefitted from his advocacy, it cast the administration in a bad light.

Harry Vaughn testifying at congressional hearings on the "5 Percenter" controversy (Image source: Truman Library)

“Deep Freeze” referred to one aspect of the 5 Percenter investigation that did resonate with the wider public. Hoey’s hearings revealed a story from 1945 about how General Vaughn and other high-level Administration figures, including the President’s wife Bess, and been gifted deep freezers by wealthy friends with connections to an appliance manufacturer, one of the machines being delivered to the Truman residence in Independence, Missouri. Although a trivial incident in itself, the very ordinariness of those consumer appliances which were otherwise difficult to acquire during wartime struck a public nerve, as did Vaughn’s evasive attempt to explain the gifts away. “Deep Freeze” henceforth became a shorthand reference to influence-peddling in the Truman White House.

“Mink Coat” / “Mink Standard of Value.” For Homo americanus expenseaccountis of the early to mid-20th century, adorning a favored woman in the sewn pelts of small carnivores was a typical way of conferring both affection and status upon the female. On both these scrip notes, the references to mink coats were nods to a second scandal that vexed the Truman Administration, this time focused on the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). A storied federal agency, the RFC had been created by Herbert Hoover in 1932 to recapitalize vulnerable banks, insurance companies, and other corporations during the Great Depression; under Roosevelt, the agency continued to play major roles during the New Deal and World War II. By the late 1940s, however, the RFC had outlived its usefulness and was beset by allegations that its loan policies were subject to political influence (by 1953, the RFC would be repurposed as the Small Business Administration). Moreover, RFC staffers had acquired a habit of finding lucrative employment opportunities with the very companies to which the RFC had lent funds. All of this became grist for another congressional investigation, this time directed by Arkansas’s Senator J. William Fulbright, beginning in mid-1950.

The Fulbright committee’s scrutiny put Truman on the defensive, particularly as it shined a spotlight on another official close to the President, his Personnel Director Donald S. Dawson. Dawson, formerly with the RFC, was accused of exercising undue influence over its Board of Directors and its loan approvals. The issue of the mink coat emerged in February 1951, when Fulbright’s preliminary report revealed that a former loan examiner at the RFC named E. Merl Young had given a “natural royal pastel” mink coat to his wife, who at the time was working as a stenographer in the White House. The cost of the coat, which retailed at an eye-watering $9,500, had been charged to a lawyer whose corporate client (for whom Young by that time had just happened to be working) had a loan application pending before the RFC.

Thus, as with the “Deep Freeze”, “Mink Coat” became a second public symbol of the sleazy reputation of the Truman Presidency. To critics, the career of E. Merl Young in particular was emblematic of how influence operated in Washington. An unknown with no particular background, Young moved up and cashed in by glad-handing and ingratiating himself with others, even exploiting unfounded rumors that he was President Truman's nephew. The symbol of the "Mink Coat" also occasioned some clever Republican campaign slogans in the 1952 election, such as “No Pinks, No Minks” and “The only thing Democrats have to fear is—fur itself.” The mink coat controversy even figured in one of most famous rhetorical exercises in American political history, Richard Nixon’s “Checkers Speech” of September 23, 1952.

Chosen as Eisenhower’s running mate at the party’s July convention, Nixon later came under fire for the existence of a campaign slush fund that was threatening his position on the Republican ticket (it later turned out that other major politicians maintained similar kitties, including Adlai Stevenson himself). In a nationwide television address that was unprecedented for the time, Nixon declaimed, in maudlin detail, the financial particulars of his family’s modest lifestyle, including these now-memorable lines about his wife: “Pat doesn't have a mink coat. But she does have a respectable Republican cloth coat. And I always tell her she’d look good in anything.”

The “Grain Scandal” and “Tax Scandal”

Two further references to Truman Administration missteps appear on the Mantooth-Fulshear note, but not on the Women’s Brigade for Eisenhower note. The first, “Grain Scandal”, again involved General Vaughn and came to light during Senator Hoey’s five-percenter investigation. In this instance, Vaughn was accused of having interceded improperly with the Department of Agriculture on behalf of distillers, who were seeking to divert grain supplies from food channels into alcohol production.

The second reference to “Tax Scandal” touched on what became the most serious ethical problem facing Truman. This was the pattern of corruption that emerged at the Bureau of Internal Revenue (BIR), forerunner of the present-day IRS. As with government procurement and government-mandating rationing, the tax system during wartime expanded rapidly and far beyond the government’s capacity to collect revenues professionally. At the time, revenue collectors were still traditionally patronage appointments. Occupants of those offices were not civil servants and moreover were allowed to pursue simultaneously their private businesses. Reports of favoritism, bribery, and even outright theft in BIR offices cropped up across the country, prompting yet another congressional investigation throughout 1951, this time led by Rep. Cecil R. King (D-CA).

Unlike other scandals besetting the Truman Administration, this one was not only substantively more serious but led to resignations, firings, and even convictions for high-level officials. The damage spread from regional revenue collectors to include Administration figures like T. Lamar Caudle, Assistant Attorney General responsible for tax enforcement (fired, later convicted) and his counterpart in the BIR, Chief Counsel Charles Oliphant (resigned). Caudle’s testimony before King’s committee revealed, among other things, yet another mink coat incident, this time one purchased by Caudle for his wife with the help of a tax attorney who had business before Caudle’s office.

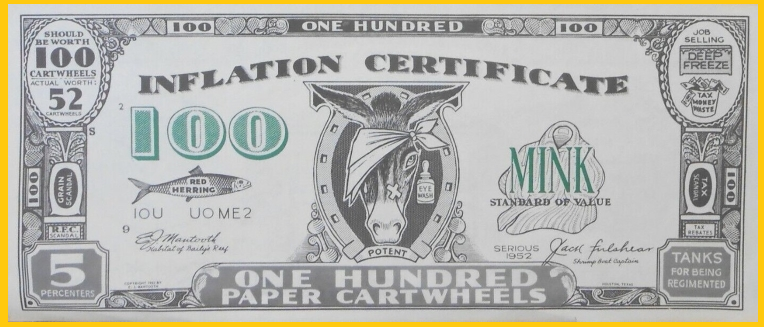

ABOVE: A political token expressed the contrasts that Truman's scandals allowed Republicans to make in their election campaign. BELOW: the Truman scandals on postcards. (Image sources: TAMS Journal; Ebay).

In the 5 percenter and RFC investigations, Truman was able to stiff-arm Congress in a way that kept his aides Harry Vaughn and Donald Dawson in their jobs. However, given the seriousness of the BIR scandal the Administration struggled to stay ahead of the spreading revelations, appearing to respond only when pressured by Congress. By early 1952, the Administration even botched a plan to appoint an independent investigator, which led to the forced resignation of Attorney General J. Howard McGrath in April. All of this took place as the Presidential election season was gearing up, which put the Democrats in the terrible position of defending themselves against what even their own Democratic candidate, Adlai Stevenson, seemed to acknowledge was the “mess in Washington.”

Price Inflation and the 1952 Election

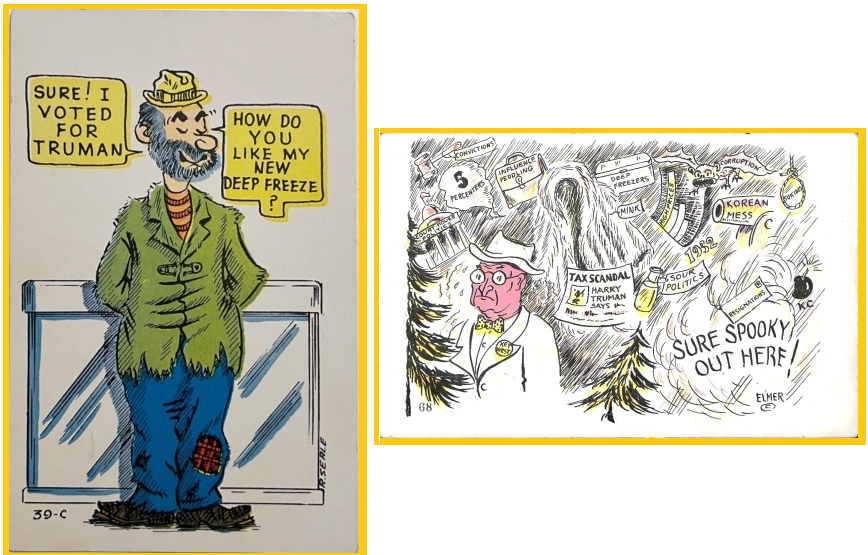

Although corruption became for these reasons a major theme of the November 1952 election, Eisenhower pounded the Democrats on the issue of inflation, as well. The name that the Women’s Brigade for Eisenhower had given to their scrip, “Truman Dollar”, had also become a more general shorthand to describe the price inflation that Americans had experienced in recent years. As with the Mantooth-Fulshear “Inflation Certificate” described above, the public discourse about inflation, common throughout the newspapers in 1952, reflected the reporting convention practiced by the U.S. government’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, which at that time had been calculating changes in the Consumer Price Index using January 1939 as the base year for comparison. According to the BLS, the purchasing power of the dollar between 1939 and 1952 had fallen by about fifty percent (i.e. prices had nearly doubled). Most of this decline reflected the inflation induced by World War II, and between 1948 and 1950 price increases seemed to have stabilized. However, with the onset of the Korean war inflationary pressures returned, creating a renewed headache for elected officials.

Throughout the years of conflict, the Federal Reserve had accommodated war financing by pegging interest rates at artificially low levels. With the Fed-Treasury Accord of March 1951, the central bank had only very recently re-asserted its independence. Under these circumstances, the public debate about inflation played out in a very different way than it would in the 21st century. Rather than focus on the Federal Reserve and its monetary policy as bearing any responsibility for inflation, the public ignored the central bank and instead placed the blame squarely upon the Truman Administration. Unfortunately for the Democrats, the term “Truman Dollar” became an epithet not just hurled by Republican politicians but put to use by ordinary Americans to express their frustrations with the eroding purchasing power of the currency.

Classified advertisements of 1952 suggest how widespread the use of the term "Truman Dollar" was. These ads appeared in newspapers from Akron, OH; Billings, MT; Columbus, OH; Chapel Hill, NC; Miller County, MO; Palm Beach, FL; and Santa Rosa, CA.

Ike’s “Donkey Dollar”

Seeking to appeal to these frustrations, Eisenhower incorporated the inflation issue into his stump speeches in a simple but effective way. Rounding the numbers somewhat, Ike repeatedly charged that, under the Democrats’ mismanagement, the value of the dollar had fallen by half between 1940 and 1952. He would illustrate this fact at podiums by waving a dollar folded in half at his audiences. In late September 1952, he embarked on a whistle-stop campaign across Illinois and Indiana, giving speeches during which he brandished a new prop, the “Donkey Dollar”, that refocused the inflation issue away from Truman specifically (who was not a candidate) and towards the Democratic Party as a whole. About half the size of a regular dollar bill, this note warned its recipients “don’t let the Donkey Dollar make a jackass out of you,” text which Eisenhower would recite to his listeners.

ABOVE: Candidate Eisenhower waving "Donkey Dollars" during a late September speech in Indiana. BELOW: the front and back of the "Donkey Dollar". (Image Sources: The Eugene [OR] Guard, September 17, 1952; Heritage Auctions).

Two versions of the “Donkey Dollar” were produced and distributed to voters, one a bit more currency-like than the other but both featuring the identical language. The context of Eisenhower’s remarks made clear what “12 years under the Democrats” referred to. Eisenhower meant the value of the dollar in 1940, relative to where it was in 1952, not in 1932, when FDR won his first term. Assuming the earlier date, these “Donkey Dollars” have sometimes been attributed mistakenly to the 1944 or 1948 elections. Newspaper accounts, though, clearly make reference to this scrip as an artifact of the 1952 contest.

Conclusion: Truman and the Legacy of Corruption

Given the stiff political headwinds facing the Democrats, the Nixon-Eisenhower ticket delivered them a thumping in 1952 and even returned Congress (albeit temporarily) to Republican control. Truman had inherited FDR’s policy agenda and sought to consolidate its achievements under his rubric of the “Fair Deal.” Yet after twenty years of Democrats in the White House, Americans simply wanted a change. Even without the Truman-era scandals, Eisenhower was appealing as a relatively non-partisan figure who kept daylight between himself and the more conservative Taft wing of the Republican party (indeed, Truman had unsuccessfully reached out to Ike to get him to run as a Democrat). Thus, a Democratic-leaning voter distressed with the Truman scandal record could switch to Eisenhower without worrying about the New Deal being eviscerated.

While Truman chose not to run in 1952, unlike Johnson in 1968 he did not exactly cede the field to his successors. Despite the “mess in Washington” being one theme of the election contest, Truman insisted on campaigning vigorously for Adlai Stevenson even though latter regarded the Truman White House as something to distance himself from. Although loyal to his party, Truman invariably saw the election as a referendum on his legacy which he sought to defend, even if that wasn’t in the best electoral interests of the ticket.

After the November outcome, the syndicated columnist Walter Winchell, the kind of newspaperman whom Truman despised, was unsparing in his judgment:

“Eisenhower’s sweep is as much a tribute to his personal popularity as it is a repudiation of the Truman Administration ….The American people just ran out of patience with an Administration that walked out on FDR’s ideals ….The crushing defeat of Trumanism is intensified by the fact that the trouncing happened during a time of national prosperity. Apparently, you cannot buy the support of Americans with Truman dollars. It must be earned with simple decency. Ironically, one of the prime factors that made possible the Republican triumph was the Truman record.”

In contrast to his original political mentor, Tom Pendergast, Truman himself professed high standards of personal rectitude. Later historians of his Presidency concur that he was an honest man. The same cannot be said of his subordinates. The problems of graft and corruption in the Truman Administration, conditioned as they were by the rapid expansion of federal government power since the 1930s, were fundamentally enabled by Truman’s own political upbringing. Given his origins as a machine politician, Truman accepted as a matter of course patronage as a principle of party organization. As a corollary to this, Truman prized loyalty and practiced it with his staff, particularly towards those whom he considered members of his ‘family.’ Somewhat speciously perhaps, Truman distinguished between patronage itself and the excesses of graft, fraud, and influence-peddling, as if the latter were not a predictable consequence of the former.

As a result, Truman showed forbearance towards wayward staff (Vaughn, Dawson, etc.) who ought to have been shown the door. Worse, Truman’s indulgent attitude towards patronage also led him to underestimate the seriousness of the most substantive scandal under his watch, that involving the Bureau of Internal Revenue. However, in the public eye, it remained the squalid ordinariness of the “deep freeze” and “mink coat” episodes that gave plausibility to the claim, printed on the back of Mantooth’s and Fulshear’s note, that “this certificate is no good unless you know someone in Washington.”

REFERENCES

Abels, Jules, The Truman Scandals (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1956), pp. 86-95, for sketch of E. Merl Young's activities.

Ancestry.com, for G. N. Fulshear’s WWI and II draft cards with his employment information.

Austin (TX) American, May 3, 1922; June 9, 1925; December 9, 1929, for references to Fulshear's employment.

Austin (TX) Statesman, June 6, 1925; September 26, 1926; November 20, 1929, for references to Fulshear's employment..

Dry Goods Merchants Trade Journal, November 1927, p. 41, for picture of Fulshear.

Dunar, Andrew J., The Truman Scandals and the Politics of Morality (University of Missouri Press, 1984), esp. chs. 3-6.

The Eugene (OR) Guard, September 17, 1952. The same story and picture appeared in multiple newspapers around the country around this time.

Los Angeles Times, September 25, 1952; October 1, 1952; October 18, 1952.

Lubbock (TX) Evening Journal, November 13, 1952, for Winchell’s column, which appeared in newspapers around the country.

Martin, Nick, “Scandals and Minks: Heads, Tails, and Politically Correct” TAMS Journal (February 2006), pp. 7-9.

Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, June 1, 1952, for a profile of the Kaiser and Mantooth-Fulshear currency parodies.

Pendergrass, John, “I Want a Mink Coat” The Keynoter (Winter 1986), p. 40.

Pendergrass, John, “The ‘Red Herring’ in American Politics” The Keynoter (Spring-Summer 1990), pp. 17-19.

Ross, Steven J., Hollywood Left and Right: How Movie Stars Shaped American Politics (Oxford University Press, 2011), p. 86.

Tyler (TX) Morning Telegraph, March 21, 1952, on the “Inflation Certificate.” Versions of this story appeared in multiple newspapers across the country.