Politics and Paper Money

Ezeemunny, Dopey Dough, and California’s Ham and Eggs Movement

BY THE END OF THE 1930s, Americans had seen a lot of (and perhaps had enough of) scrip and other unofficial alternatives to the U.S. dollar. Even well into the decade, however, the state of California remained stubbornly receptive to monetary nostrums for economic recovery. Beginning with the Townsend movement in 1933 (which proposed old-age pension payments juiced with a money-velocity feature), followed by Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California plan of 1934 (state-issued scrip to finance agricultural and industrial production), the Ham and Eggs movement that emerged later in the decade pushed yet another old-age pension scheme, this time financed by statewide issues of self-liquidating stamp scrip. Officially named the Retirement Life Payments Act, the pension initiative operated under the slogan “Thirty Every Thursday” ($30 worth of scrip each week to eligible pensioners). Masterminded by a motley collection of money cranks and political grifters and opposed by almost every major economic interest in California, Ham and Eggs nonetheless came closer than the other monetary nostrum to being put into effect, falling short in a 1938 state ballot initiative by only a few percentage points of the popular vote.

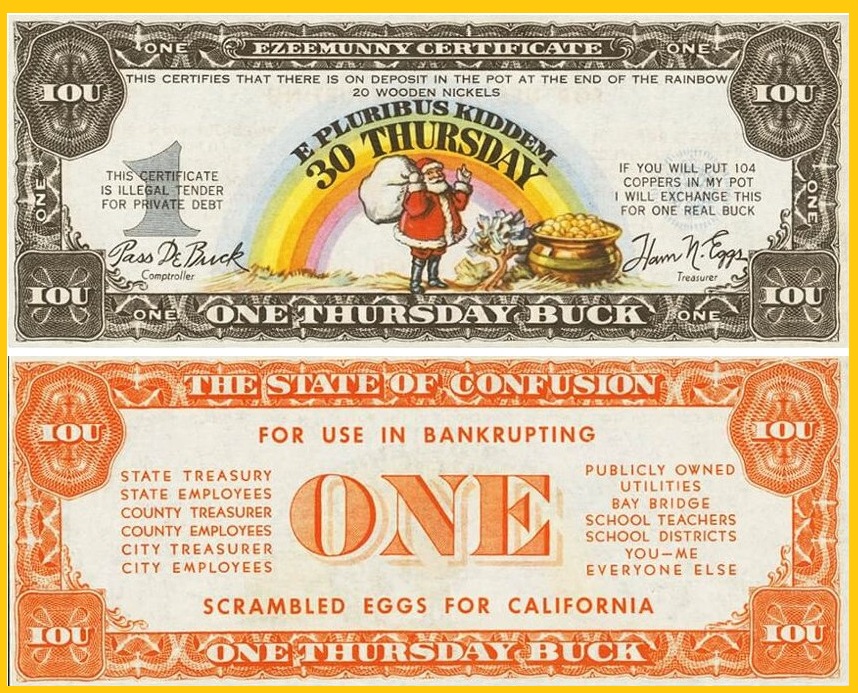

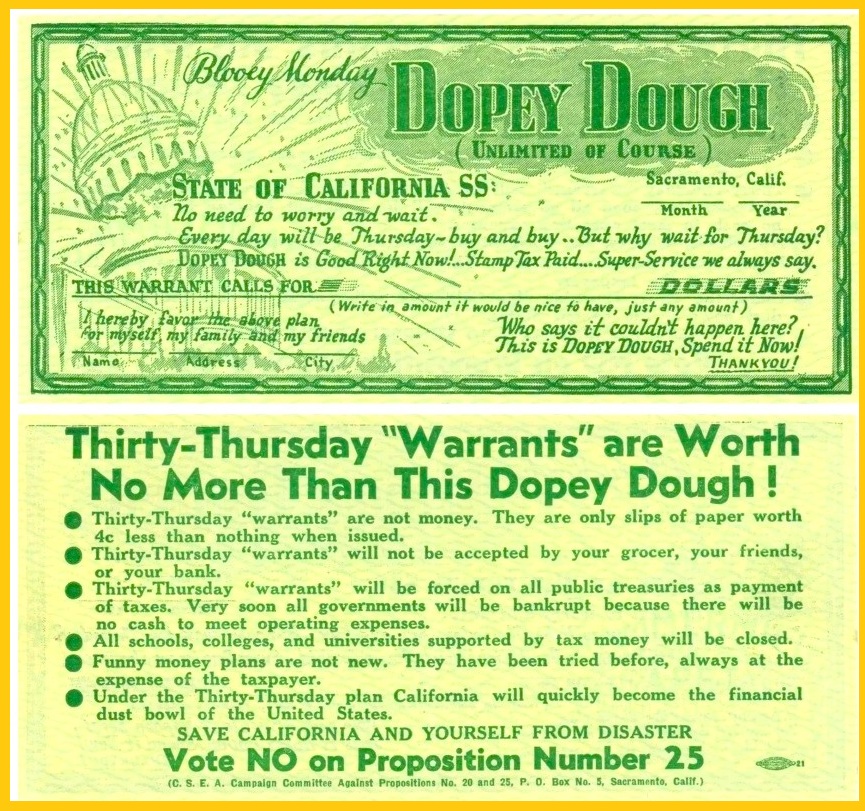

The two pieces of satirical currency depicted here, Dopey Dough and the Ezeemunny Certificate, were circulated in late 1938 by opponents of that Ham and Eggs plan.

Above: Front and back of an Ezeemunny Certificate issued by the California State Chamber of Commerce. Below: Front and back of a Dopey Dough warrant, issued by the California State Employees Association. Both appeared in early October 1938. (Image sources: Heritage Auctions, above; California State Archives, below).

How Ham and Eggs Got on the Menu

California in the 1930s was receptive to pension activism because of its large elderly population. Rising living standards and longer life expectancies had made possible the concept of retirement as a stage of life for larger numbers of older Americans, who flocked to California for its sunny and temperate climes. At a time before publicly funded old-age insurance programs provided a consistent safety net, elderly nonworking Americans depended upon a mix of family support, company pensions, and private savings to sustain themselves. Many of these resources shriveled with the onset of the Great Depression.

As the elderly fell into penury, they became receptive recruits for political entrepreneurs seeking a support base for various pension proposals. Beginning with Francis Townsend’s Old-Age Revolving Pension Plan of 1934, which grew to become a national phenomenon, pension activism generated numerous proposals that complicated political life in California and elsewhere. While the Social Security Act had been passed in 1935, this linchpin of the New Deal was not slated to begin making payments until the early 1940s, thus creating a political space that could be filled by rival alternatives. For conventional politicians of either a liberal or conservative bent, pension panaceas were vexing because, although their fiscal implications might be massive and unrealistic, their advocates and their followers certainly did not see themselves as nefarious interest groups pushing radical ideas. Indeed, pension advocates were adept at casting their arguments in terms of depression era economics: money velocity would quicken; increased purchasing power would stimulate the economy; youth employment would increase when the elderly could more easily retire, and so forth. Wanting to court the elderly vote but wary of offending organized business and financial interests, politicians vied to signal their sympathy for such pension proposals without actually making a firm commitment to implement them.

What later became known as the Ham and Eggs movement began with the efforts of a California radio personality, Robert Noble, to promote a version of Irving Fisher’s stamp scrip proposal as a mechanism for funding old-age payments. Noble, who had earlier dabbled in the Townsend movement and Upton Sinclair’s EPIC campaign, came upon an account of the eminent Yale professor’s plan to stimulate purchasing power and increase the velocity of currency circulation by issuing a form of paper money that required the application of a stamp at regular intervals. The idea behind the stamps was that purchasing (with U.S. money) and affixing them would build up the redemption fund that would eventually retire the scrip—hence the frequent description of stamp scrip as a “self-liquidating” currency.

Promoting the Fisher's plan on his radio broadcasts, Robert Noble soon built up a large following of elderly listeners who gladly contributed small monthly dues—one cent a day, or thirty cents a month—to be part of the burgeoning network of clubs that advocated for California pensions financed by a state issue of stamp scrip under the slogan “$25 every Monday.” The cash flow that Noble’s operation generated soon enticed two of his associates, the brothers Willis and Lawrence Allen, to take over the organization, force Noble out, and reorganize it as the Retirement Life Payments Association with a more alliterative slogan, “Thirty Every Thursday.” A sketchy pair, the Allens operated an advertising agency in Hollywood and soon replaced Noble’s broadcasts with their own radio content. Gaining legislative approval for the plan was not a possibility, so the goal of this agitation was to canvass enough signatures to place the plan before California voters as a ballot initiative. The resulting petition, which garnered nearly 800,000 names, ensured that what became Proposition 25 would be put on the ballot for early November 1938. Although the moniker was unofficial, “Ham and Eggs for California” soon became the shorthand name for this looming pension initiative.

Like the Townsend Plan, the basic features of the Ham and Eggs idea evolved over time. The proposal that went before the voters in 1938 provided for weekly payments of thirty dollars’ worth of state scrip (officially, “California Retirement Compensation Warrants”) that would require the weekly use of a 2 cent stamp to keep them valid until the fund accumulated that would retire the each note after a year’s circulation (2 cents times 52 weeks generated $1.04, the four cents going towards administrative costs). Any retired person over the age of 50 was eligible to receive a pension. Ham and Eggs scrip would be acceptable for state tax payments. Moreover, any transactions using the scrip (except gasoline) would be exempt from state sales taxes; likewise, earnings in scrip would be exempt from state income taxes. State employees would receive their pay half in the new stamp scrip, the other half in U.S. funds.

The plan’s campaign literature, notably a volume entitled Ham and Eggs for Californians (1938), hazily implied that there was widespread expert support for the scrip idea. This simply was not true. Irving Fisher himself spoke out against this appropriation of stamp scrip, which he had advocated only as local experiments in economic revival. Careful not to call this money, instead the campaign referred to the proposed emissions as “self-liquidating, non-interest bearing promissory notes or baby bonds.” It employed a mish-mash of arguments which borrowed from underconsumptionist ideas that were commonplace in the public discourse of the 1930s; it also gestured towards concerns about machines-replacing-humans that were a staple of Technocracy. The overall impression given by the tract was that, far from being a budget-busting giveaway to oldsters, Ham and Eggs represented genius social engineering. It promised to take from nobody and give to everybody. No organized social or economic interest could possibly be against the plan, since it a) restored consumer purchasing power, thus goosing the economy; b) was self-financing (no tax increases necessary!); c) was non-inflationary, because of the scrip’s self-liquidating feature; and d) promoted youth employment by encouraging the elderly to retire. In short, Ham and Eggs promised to shift not just California, but the nation itself, from an “economy of scarcity” to an “economy of abundance.”

This "Pension Plan locomotive" traveled the state, drumming up support for the Ham and Eggs campaign. Pictures of this vehicle appeared in California newspapers in early October 1938. (Image source: Alamy).

Ezeemunny and Dopey Dough

The problem with these arguments was their corollary: If you were not in favor of the Ham and Eggs idea even in the face of all its advantages, then you were either hopelessly stupid or intentionally malevolent. As business and financial groups lined up against the ballot initiative, the rhetoric of the Ham and Eggs campaign, which had affected an apolitical nonpartisanship, grew increasingly populist and conspiratorial in tone as election day neared, inveighing against “tory bankers and economic royalists” of the California business elite. The two notes illustrated here reflected the sharpening of the battle lines. Both were put into circulation by opponents of Ham and Eggs in early October of 1938. The Ezeemunny Certificate received by far the greater publicity. Although the note does not identify who issued them, they were widely attributed to the California State Chamber of Commerce, which produced and distributed them in large numbers and are commonly available today. Facsimiles appeared not just in newspapers across the country but in the foreign press as well.

As a piece of satire, the Ezeemunny Certificate was striking for its vibrant color and professional execution. Slightly smaller than a one dollar bill, the front features, somewhat incongruously, an image of Santa Claus with his sack of goodies juxtaposed against a rainbow anchored with the proverbial pot of gold which, in actuality, contains nothing but “wooden nickels.” The text to the right adds, “if you will put 104 coppers in my pot I will exchange this for one real buck,” alluding to the funding mechanism of Ham and Eggs. This imagery implied that Ham and Eggs supporters were beguiled by its illusory promise of prosperity and by the prospect of getting something for nothing. The back of the note makes more direct assertions about what would happen if the initiative passed. Rather than engaging with the Ham and Eggers’ nebulous economic declamations about underconsumption and technology, the text instead raises specific fears all related to public finance: bankruptcy for state, county, and municipal governments, thus resulting in “scrambled eggs for California.”

References to the Dopey Dough note also appeared in newspapers at about the same time. Styled as a burlesque on a municipal warrant, this note identified its source on the back as the “C.S.E.A. Campaign Committee Against Propositions 20 and 25.” This was the California State Employees Association, which was taking a position both against Proposition 25 (Ham and Eggs) and Proposition 20 (a proposal to phase out the state’s sales tax). Core to their opposition was the prospect of civil servants receiving up to half their pay in this untried and experimental currency. Once the California Bankers Association announced that its members would not accept the pension warrants on deposit, the hostility of state workers to Ham and Eggs became a foregone conclusion.

Larger and more crudely produced than the Ezeemunny Certificate, the front of the Dopey Dough note depicts the exploding dome of the California state capitol and invites its holder to fill in whatever “amount it would be nice to have, just any amount.” Much wordier than Eezymunny, the reverse details various fiscal calamities which will befall California, the gist being that Ham and Eggs warrants would not supplement existing money but drive it, Gresham’s Law style, from circulation. As a result, the note alleged, Ham and Eggs would turn California into the “financial dust bowl of the United States.”

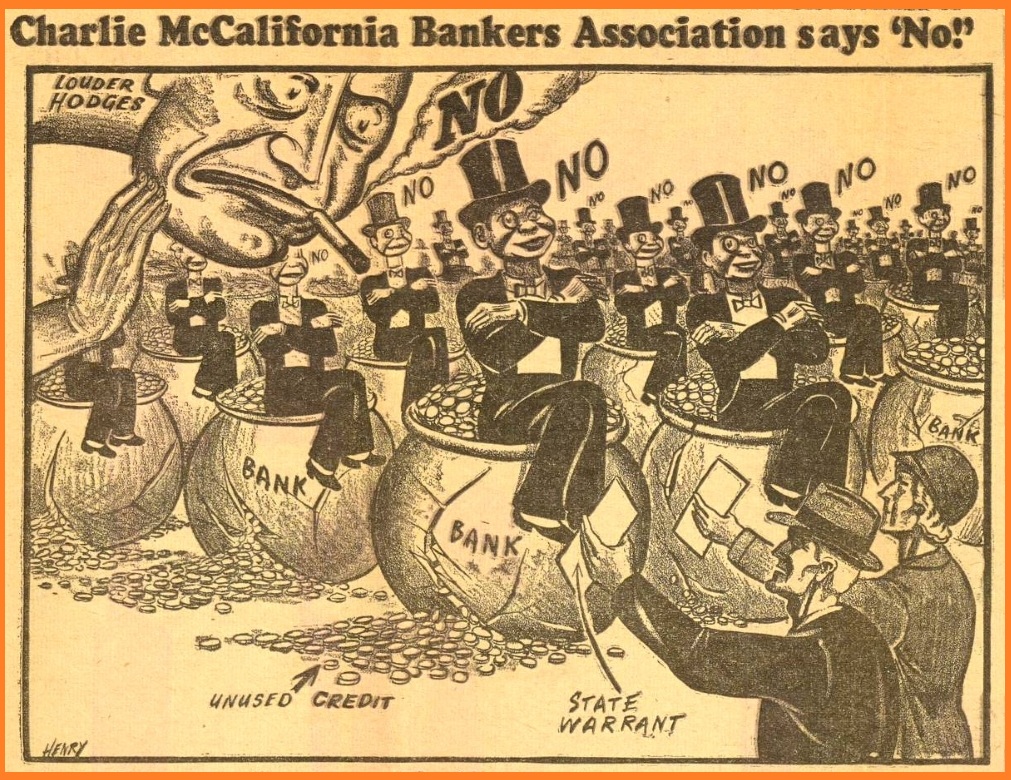

Key to the feasibility of Ham and Eggs was the negotiability of its pension warrants. The state bankers' refusal to accept them provoked this cartoon attack from Ham and Eggers. "Louder" [Lauder] Hodges was executive manager of the California Bankers Association. (Image source: Ham and Eggs for Californians, September 24, 1938).

Ham and Eggs and American Politics

Although Proposition 25 fell to defeat in November 1938, the margin of loss was not great, which motivated its promoters to organize for a second initiative campaign. More importantly, the Retirement Life Payments Association was buoyed by the steady flow of small-money donations, which naturally the Allen brothers continued to funnel through their advertising agency. A second petition garnered even more signatures than the first one and a repeat vote on a revised version of Ham and Eggs was duly scheduled for November 1939. The new plan, which provided for a state bank to manage the warrants and a 3% income tax to finance the plan, put off more supporters than it gained, resulting in a more decisive defeat.

Although Ham and Eggs never made it to the ballot again, its effects upon California and national politics were longer lasting. Generally, it boosted Democratic candidates in 1938, since the Republican party had come out against the measure. Ham and Eggs helped Culbert Olson to become California’s first Democratic governor in over 40 years, while Sheridan Downey, whose support for Ham and Eggs was more explicit, bested Senator William Gibbs McAdoo in a primary election despite President Roosevelt’s opposition. Leery of offending older voters, politicians waffled on Ham and Eggs if they could. The elderly represented a powerful voting bloc, although their salience would later decline as California’s demographics skewed younger after the Second World War. Ironically, the Ham and Eggs movement was more influential as long as it didn’t become too identified with party politics. Once it took partisan sides, it invariably split the base upon which it relied for support.

.....

REFERENCES

Gatch, Loren, “A Satirical Note on the ‘Ham and Eggs’ California Scrip Pension Initiatives of 1938-9” Paper Money (November/December 2008): 459-461.

Ham and Eggs for Californians. Life Begins at Fifty. $30 a Week for Life (Hollywood, CA: Petition Campaign Committee,1938).

Ham and Eggs for Californians, Vol. I, No. 1, September 24, 1938 (this shares the name of the campaign tract but appeared as a separate newspaper).

Los Angeles Times, September 20, 1938.

Mitchell, Daniel J. B., “The Lessons of Ham and Eggs: California’s 1938 and 1939 Pension Ballot Initiatives” Southern California Quarterly (Summer 2000): 112-132.

Moore, Winston, and Marian Moore, Out of the Frying Pan (Los Angeles, CA: DeVorss & Co., 1939).