Politics and Paper Money

Frank C. Hughes’s "New Deal Sound Mazuma"

FRANKLIN DELANO ROOSEVELT’S policy response to the economic collapse of the 1930s, the New Deal, was a complex affair that had many moving parts. Some elements, like the National Recovery Administration (NRA) or the various work-relief programs, were either struck down by the courts or did not last longer than the depression itself. Others, like farm support, deposit insurance, or old age pensions, became enduring features of the national political agenda.

Whether foolish or sensible individually, the collective impact of these New Deal measures was to reorient Americans’ attitudes towards the national government and to change their expectations about what that government should do for them. This transformation of government evoked a particularly visceral reaction from those who thought that the New Deal betrayed core American ideals of individualism and self-reliance. While Roosevelt’s re-election inf 1936 signaled broad support for the path he was taking, opposition nonetheless remained bitter. Indeed, as the President declared of his opponents on the eve of that election, “they are unanimous in their hate for me—and I welcome their hatred.”

One such Roosevelt antagonist was Frank C. Hughes, a resident of the summer community of Squirrel Island, Maine. A private citizen with no record in public office other than an early stint as a justice of the peace, Hughes was a minor but persistent critic of the New Deal who regularly sent his acerbic assessments to newspapers across the country.. An inveterate letter writer to both the press and to prominent public figures of the time, Hughes collected his observations (and some of the offended responses to his missives) into self-published pamphlets which he then endeavored to distribute. Hughes was also a fervent campaigner for agnosticism and atheism. In Hughes’s synthesis, the same human flaws and frailties that sustained organized religion were also those that made the New Deal possible. Both, in his view, were “rackets” that enabled self-interested elites to fleece the gullible.

A cantankerous individual, Hughes came off at times as either cranky or simply a crank. Although in his politics he remained resolutely Republican, by the 1940s and 1950s he proclaimed himself “Pope of the Bad Lands” and shifted his focus to the promotion of atheism and the separation of church and state, topics which he addressed with militant enthusiasm through both his writings and various legal actions.

In his crusade against the New Deal, Hughes was responsible for producing one of the more memorable pieces of anti-Roosevelt propaganda, the “New Deal Sound Mazuma” parody note of 1936.

Frank C. Hughes, New Deal Critic

Frank Charles Hughes (1882-1961) was born in Yankton, South Dakota, one of five children of Alexander Hughes, a prominent businessman and public figure in what was then the Dakota Territory. After attending public schools in Bismarck, North Dakota, Frank Hughes studied at the University of Minnesota, where he graduated in 1903 with a degree in mechanical engineering. The next year he moved to Glendive, Montana, a city situated on the Yellowstone River and adjacent to Montana’s Badlands. There, he worked for a company owned by his father, the Hughes Electric Company, which operated a string of electric utility and phone concerns across Montana and North Dakota. In 1905 he married Nell V. Ditman at Glendive. With the death of his father in 1907, Frank Hughes assumed control of the operations in Glendive, which he operated and expanded until selling out in 1918. He and Nell moved to Evanston, Illinois in 1919. There he worked as a manager with an electrical supply company run by one of his brothers. Several years later Nell fell sick and, despite treatment in Rochester, Minnesota, died in 1925. A second marriage ended quickly in divorce, while a third, to Gertrude Ballard on New Years Day 1931, proved enduring.

Frank and Gertrude Hughes, circa 1940 (Image source: photograph taped into copy of Hell and Amen).

At this point in life Frank Hughes, in his late forties, was independently wealthy, dabbling in stock speculation and tending to his remaining oil interests in Glendive, with whose residents he maintained strong ties and which he continued to visit regularly. Frank and Gertrude soon began dividing their time between Squirrel Island, Maine, a summer-only resort community in the Gulf of Maine, and Minneapolis during the winters. As the economic depression of the early 1930s persisted, Hughes began penning letters to the Glendive newspaper expressing his views about the darkening situation. It was the rise of Roosevelt as a candidate and his victory in the Presidential election of 1932 that really energized Frank Hughes’s writing career. Not only did he express a Republican’s conventional aversion to unbalanced budgets and big government, he also regarded the New Deal and its proliferating, bureaucratic “alphabetical catastrophes” as a threat to basic American values. To Hughes, the pros and cons of any specific policy were not up for debate. Rather, Hughes viewed the entire New Deal itself as a vast engine of corruption through which Democratic politicians (and FDR especially), bought the loyalty of voters by degrading their characters. As he put it a missive from May 1934, “destroy the initiative and ambition of our citizens and you will increase the percentage of weaklings who will vote the Democratic ticket, but you will completely destroy the nation.”

New Deal Sound Mazuma

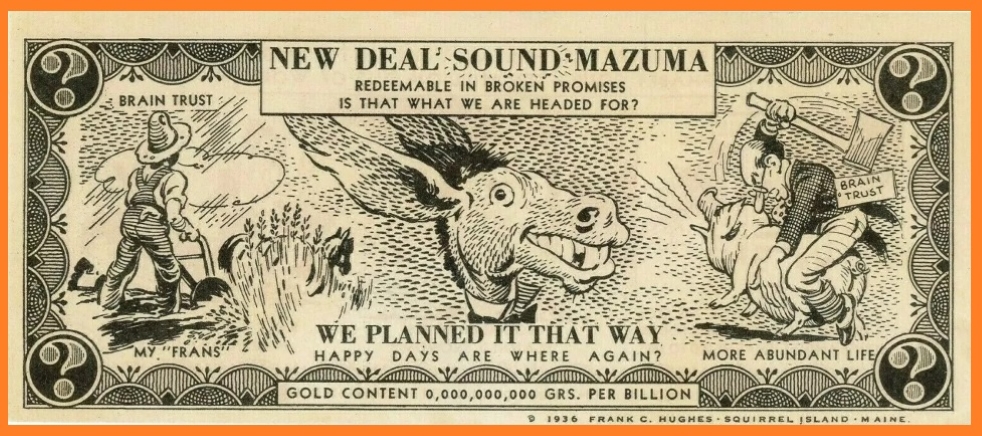

It was this loathing of what the New Deal stood for that motivated Hughes’s production of the “New Deal Sound Mazuma” note of 1936. A clever riff on various New Deal policies, the note measures 2 ¾ by 6 ¼ inches. On the front of the note, beneath the assurance that it is “redeemable in broken promises” appears a grinning, gap-toothed donkey, under which is the caption “WE PLANNED IT THAT WAY—Happy Days are Where Again”, the latter phrase a twist on the popular Ager and Yellen song title associated with FDR’s 1932 campaign. To the left and right of the donkey are depictions of two controversial aspects of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933: the plowing under of crops and the slaughter of farm animals, particularly pigs. Based on the premise that low farm prices were a consequence of overproduction, the AAA sought to reduce supplies of agricultural commodities, even as many Americans went hungry during the depression. The resulting contrast was deeply unintuitive, especially the prospect that, thanks to the AAA, farmers would be paid NOT to produce their crops. On the right, a professorial-looking axe wielder goes after a squealing pig, the label “brain trust” suggesting that only some intellectual from among Roosevelt’s policy circle could be so clueless as to propose that prosperity would ensue from destroying resources. On the left of the note under the vignette of a farmer plowing under his wheat appears the words, “My ‘Frans’” [friends], which was FDR’s characteristic way of addressing the American people, “Frans” being the way journalists in the 1930s commonly transcribed the twang of the President’s Mid-Atlantic accent.

Appearing at the bottom of both sides of the note is a reference to its zero-gold content, reflecting Roosevelt’s suspension of the gold standard in 1933.

Front (above) and back (below) of the New Deal Sound Mazuma note. These were reportedly handed out at the 1936 Republican National Convention. (Image source: author's collection)

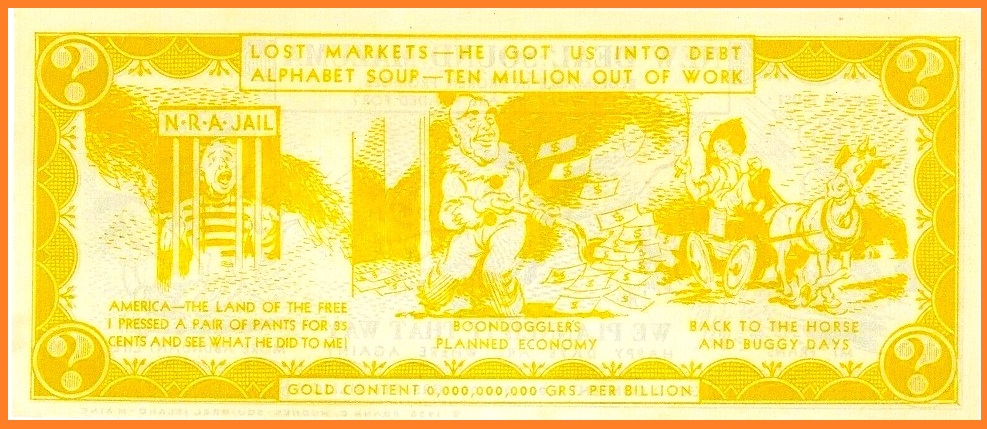

The reverse of the note takes further snipes at the New Deal, blaming the “alphabet soup” of its programs for perpetuating the slump, for mass unemployment, and for creating unsustainable debts. In the center, a man in a clown suit gleefully shovels money, while to the left another man bewails his imprisonment in an “NRA Jail” for having “pressed a pair of pants for 35 cents.” This vignette refers to an actual event in the history of the National Recovery Administration (NRA). Another basic element of the New Deal, the NRA shared with the AAA the dubious premise that low prices and wages could be remedied by limiting competition and administrative price-setting. This the NRA attempted to do by coordinating with the private sector to develop hundreds of different “industry codes” that sought to impose what the NRA defined as fair practices.

Although the federal NRA program was voluntary, some states wrote their own mandatory NRA codes into law. Thus, in April 1934 a Jersey City, New Jersey tailor named Jacob Maged was arrested, briefly jailed, and fined $100 for pressing a suit for 35 cents, rather than the state code-mandated 40 cents. The contrite tailor received a quick reprieve from his punishment when he promised to abide by the state code; however, the harsh treatment meted out to Maged, a law-abiding husband and father of four children, turned him into a potent symbol of New Deal overreach.

The final element on the reverse of the note, an old-timer preparing to leave the scene with his cart and nag over the caption “Back to the Horse and Buggy Days,” may represent Frank Hughes himself. In a number of his newspaper letters, Hughes referred in a nostalgic way to the “horse and buggy days” as that period in American life before the country was corrupted by big government.

Jacob Maged of Jersey City, NJ, NRA code victim and New Deal martyr (Image sources: Left: The Bridgerton (NJ) Evening News, April 25, 1934; Right: Getty Images).

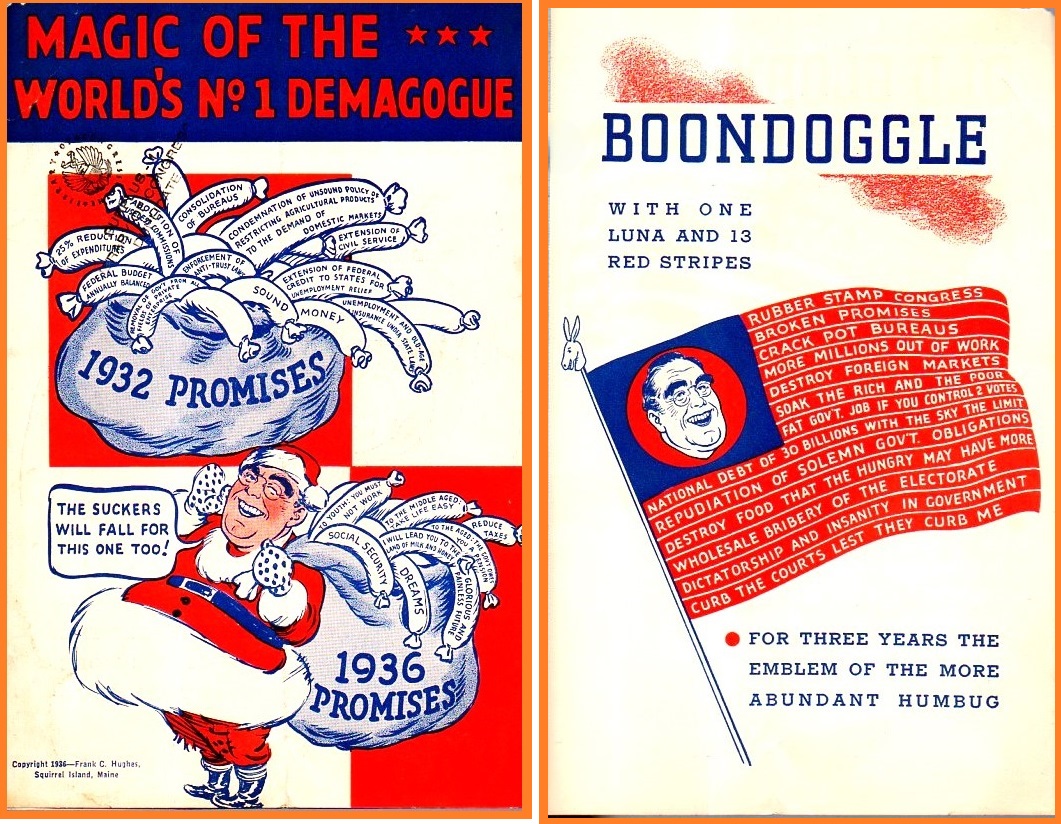

Who printed Hughes’s “New Deal Sound Mazuma” and how the notes were distributed remain unclear. Several newspaper reports in 1936 referenced the parody note, which suggests that Hughes was sending them out to Republican-friendly newspaper editors, who seemed to get a chuckle out of them. The notes also made an appearance at the Republican national convention in June 1936. As the anti-Roosevelt flyer below illustrates, the "New Deal Sound Mazuma" note was not the only piece of printing that he sponsored. Nonetheless, Hughes never seemed to have been involved in party politics or electioneering in any way, confining his activities to his letter campaigns.

Indeed, those letters that appeared in newspapers were only the tip of the Hughes literary iceberg. In 1940 he self-published a volume of some 250 pages titled Hell and Amen: The Voice of the Bad Lands, which served as a compendium of his output over the previous decade, both published and unpublished. The book made plain Hughes’s literary modus operandi. Following the appearance of a news item or in response to some other public event, Hughes regularly wrote letters to a range of public figures—President Roosevelt, his Attorney General, the Secretary of the Treasury, the Postmaster General, Charles Coughlin, the radio priest—as well as to private individuals whose names appeared in print. If his missives provoked any responses (as some recipients actually did, beyond pro forma acknowledgements), Hughes published those responses as well as his subsequent ripostes. Invariably, since nobody felt the need to continue corresponding with this unsolicited interlocuter, Hughes contrived to have the last word in any difference of opinion. He was, to use the language of the internet era, a troll seeking to get a rise out of his targets.

Front and back of an anti-Roosevelt flyer produced by Hughes the same year as his "New Deal Sound Mazuma" note (Image source: JF Ptak Science Books).

Frank C. Hughes, “Pope of the Bad Lands”

If Hughes’s initial focus in the early 1930s was the New Deal, a second strand of concern began to dominate his writings by the end of the decade, and that was religion. A devotee of the American freethinker Robert G. Ingersoll, Hughes poured his literary energy into attacking organized religion, particularly revealed religions that foregrounded beliefs in supernatural phenomena and in the possibility of divine intervention. Although Hughes did not express his beliefs in print before the 1930s, with the death of his first wife Nell in 1925, her obituary did report that the funeral ceremony was officiated by a representative of the Rationalist Society.

Although ostensibly a man of fact and science, Hughes did not seem to think that religious people could be reasonably persuaded to abandon their beliefs. Instead, Hughes evangelized for atheism by relentlessly mocking peoples’ faiths and demeaning their intelligence for subscribing to religious doctrines. Writing at a time when the cultural authority of mainline Protestantism was still ascendant in American life, Hughes took ecumenical aim at all religions, although he reserved a particular contempt for those variants of Christianity that adhered to literal interpretations of the Bible and its creation story, as well as for the Catholic Church’s embrace of saints and miracles. The practice of prayer he found patently ridiculous, particularly when it took the form of public blessings conferred by holy men.

Although during the 1930s Hughes tended to express his antipathies for the New Deal and for religion in separate letters, his critiques treated them as parallel phenomena. Both, he averred, reflected the credulity and intellectual incapacity of ordinary people to resist being scammed by self-interested elites. More particularly, Hughes linked Catholicism to the New Deal via the baleful influence of “dago and shanty Irish priests” upon the ethnic Catholic supporters of the Democratic party. As he wrote in 1940,

“all other religions have been exploited on the ‘you pay us’ plan, but New Dealism has reversed the order and substituted ‘we’ll pay you’ (out of the Federal Treasury) if you’ll join us. By its constant attacks on thrift and industry, this cult has been successful in keeping millions out of work and then it has made these sufferers believe, by Federal hand-outs, that the young God Roosevelt is their true friend.”

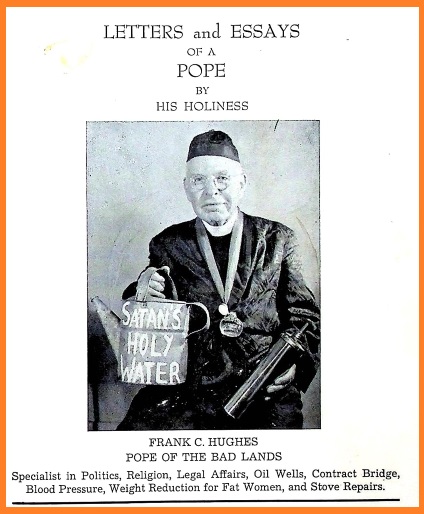

Beginning in 1941, Hughes adopted a literary persona in his crusade against religion, styling himself as the “Pope of the Bad Lands”. He continued with his letter-writing campaign, directing his missives towards newspaper editors, various public officials, and even specific private individuals whose names appeared in the news items that provoked Hughes’s responses. For example, he advised Senator Joseph McCarthy that, as long he was investigating communists, he might as well check out Pope Pius the XII, since “the fish-eaters are as obedient to his will as the Reds are to the Russian dictator.” To FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, he recommended the arrest of Satan on the grounds that putting him in jail would deprive holy men of the justification for their ministries. As with his letters from the 1930s, Hughes compiled his anti-religious missives (and any responses thereto) into a pamphlet entitled Letters and Essays of a Pope. Published in 1953, this volume featured on its cover a photograph, in remarkably bad taste, of Hughes himself dressed as a Catholic priest, wielding a watering can labeled “Satan’s Holy Water.

Frank C. Hughes, on the cover of his 1953 pamphlet, Letters and Essays of a Pope (Image source: author's collection).

Frank Hughes did not confine his disputatious energy to print but resorted to the law as well. In 1937 he took his own siblings to court, contesting their late mother’s will on the grounds that an older brother had exercised undue influence over her. When she died in 1935, Mrs. Alexander Hughes had left all her children a comfortable annuity thanks to her late husband’s fortune. Frank, however, sought to break the 1930 will, alleging that his brother Edmond had earlier contrived to place some of their mother’s assets in his own name. Making this case required Frank to prove the ugly contention that, for years, the family matriarch had actually been too senile to make responsible decisions. His three brothers and sister disagreed, and a jury found for them in a case that made national headlines.

During the same years, Frank Hughes tangled repeatedly with the Squirrel Island Village Corporation over its budgetary practices and the electric fees it charged residents. He also took aim at state-sponsored expressions of religiosity and even studied law at the University of Minnesota to sharpen his legal skills. Targets of his legal actions included: required Bible-reading in the public schools of Boothbay Harbor, Maine (1949); the use of University of Minnesota facilities for religious purposes (1951); and the paying of military chaplains by the federal government (1956). Pursued in an era before the Supreme Court had redefined church-state relations, Hughes’s legal antics went nowhere, mostly invoking editorial derision (Maine newspapers reported on his school bible-reading suit by repeatedly noting that Hughes himself was “childless”). When newspapers around the country took notice of his legal campaigns, the often made sport of the fact that he hailed from a place called "Squirrel Island", as if that unusual place name itself insinuated that there was something mentally amiss about the man. In late 1956 on the eve of the Republican national convention, Hughes’s campaign against publicly-sanctioned religious expression descended into self-parody when he announced to the newspapers his candidacy for the Presidency on the “Atheistic Ticket”, targeting “farm parity”, “foreign aid” and the “Presbyterian Church”, the last item probably a dig at Eisenhower, who several years earlier had converted to that faith.

With advancing age, Frank Hughes’s letter-writing campaign subsided by the late 1950s. While his hatred of the New Deal and his virulent anti-communism no doubt resonated with many conservative Americans, the admixture of his militant atheism rendered him an isolated figure in the broader field of American public opinion. At their best, his letters from the 1930s targeting the New Deal, particularly the ones he addressed to President Roosevelt himself, were capable of a satiric verve that compared favorably to the plain-spoken journalistic humor of Will Rogers. As Hughes’s “New Deal Sound Mazuma” note illustrated, there was indeed much about the New Deal—from the plowing under of wheat to the slaughtering of pigs to the imprisoning of people simply for having priced their services competitively—that seemed to escape common sense.

In contrast, Hughes’s many anti-religious screeds do not wear as well. Individually, his atheism-themed letters sometimes did hit their rhetorical mark. Taken together, however, the sheer repetitiveness of his derogatory diatribes, conjoined as they were with insults to the intelligence (and, often, ethnicities) of religious believers, rendered them mean-spirited, bigoted, and—worse—simply tiresome to read. Fixated as Hughes was on the incompatibility of science with faith, he placed no particular importance upon the ethical content of religious outlooks. Instead, he tended to view religions either as pathological manifestations of mass schizophrenia amongst their believers or as cynical scams to empty the wallets of the faithful into the collection plate.

One correspondence was particularly revealing of this ugly side of Hughes’s temperament. In 1946 he managed to provoke an exchange with Clare Boothe Luce, the accomplished writer, playwright, and politician who at the time was finishing up her second term in the House of Representatives. An antagonist of Roosevelt and a resolute anti-communist, Luce ought to have been just the sort of public figure that Frank Hughes would have championed. Yet, writing to her simply on the news of her conversion to Catholicism, a personal choice which had been the outgrowth of her grieving for the death of her adult daughter, Hughes’s letter was short and vicious: “I hear that the holy father has made an angel out of you,” he began. “What miracles these priests can perform . . . the churches do have pin-up girls and if you have ambitions to reach the top you must not forget that the Virgin Mary has the advantage of a publicity campaign extending over the last 1900 years . . . Balzac was right when he said, ‘After a woman gets too old to be attractive to man, she turns to God.’”

Luce had no need or reason to respond to an obscure hater like Hughes, but she did. “No doubt a letter like yours should be thrown in the wastepaper basket, where you would throw a letter written to you in a spirit as rude as your own. But you don’t sound like an altogether stupid man, in spite of the fact that it is generally stupid to be rude to people who have done you no harm . . . I don’t think you are funny at all. I think you are a very sad man really. Forgive me for not keeping quiet. ‘Out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh.’

With all best wishes, sincerely, Clare Boothe Luce.”

**********

REFERENCES

Carroll [Iowa] Daily Herald, September 1, 1936 (New Deal Sound Mazuma at the Republican convention).

Chicago Tribune, February 20, 1938 (dispute over Mrs. Alexander Hughes’s will)

The Dawson City [Glendive, Montana] Review, May 28, 1925 (death of Nell Hughes); June 8, 1931 (marriage to Gertrude Ballard); September 1, 1932 (“alphabetical catastrophes”); August 16, 1934; September 12, 1935; November 7, 1935; April 22, 1937; June 20, 1940.

The Gordon [Nebraska] Journal, October 17, 1956 (reporting on Hughes’s candidacy on the “Atheistic Ticket”)

Great Falls [Montana] Tribune, September 5, 1951 (Hughes action against Univ. of Minnesota); May 11, 1961 (Frank C. Hughes obituary).

Hughes, Frank C., Hell and Amen. The Voice of the Bad Lands (Squirrel Island, Maine, 1940).

Hughes, Frank C., Letters and Essays of a Pope by His Holiness Frank C. Hughes, Pope of the Bad Lands (Squirrel Island, Maine, 1953). Letter to J. Edgar Hoover, p. 28; letter to Joseph McCarthy, pp. 30-31; correspondence with Clare Boothe Luce, pp. 52-57.

Hughes, Frank C., “Sunday School Lessons and Bible Study. Should the Bible Be Read in Public Schools?” (East Detroit, Michigan: Michigan Liberal League, ND).

The Interlake [Kalispell, Montana], March 2, 1956 (Hughes lawsuit re military chaplains).

The Kennebec [Maine] Journal; November 15, 1937; September 16, 1939 (Hughes disputes with Squirrel Island Village Corp.)

Lewiston (Maine] Evening Journal, October 1, 1949 (Hughes lawsuit re Bible reading in schools).

The Portland [Maine] Sunday Telegram, May 7, 1961 (Frank C. Hughes obituary).

******