Bringing Vignettes to Life

Gladys

NAMED AFTER the widow of a stockholder of the railroad whose track-building gave birth to the town, Van Alstyne, Texas was first settled in 1873 and incorporated in 1890. By the turn of the century, this town straddling the border between Grayson and Collin counties hosted two national banks: the First National Bank of Van Alstyne (charter 4289), founded 1890, and the Farmers National Bank of Van Alstyne (charter 7106), founded 1903. The latter bank was organized by Charles Clinton Walsh (1867-1943) and George W. Hay (1862-1933), two brothers-in-law from Illinois who had married the sisters Emma and Ann Farnsworth, respectively. Trained in the law, C. C. Walsh later became a prominent banker as well as a business and civic leader in West Texas, eventually securing appointments as the Reserve Agent, Director, and Chairman of the Board of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

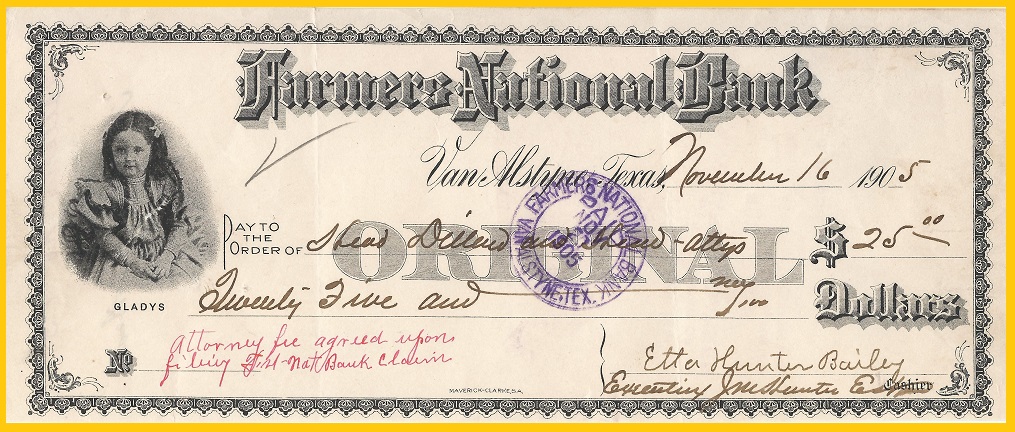

The vignette of this 1905 check written on the Farmers National Bank of Van Alstyne depicts a beribboned young girl in a dress with leg-of-mutton sleeves, a fashion style favored in the antebellum years but which came back briefly in the 1890s. “Gladys” was Gladys Alida Walsh, the daughter of Charles Clinton and Emma Farnsworth Walsh.

Born 1895 in Gonzales, Texas, Gladys was the couple’s only surviving daughter (a second child, Claire, died in infancy in 1899). Her father, C. C. Walsh, was originally from Kirkwood, Illinois. After finishing high school he taught in the state’s public schools for four years. In 1890 he married Emma Farnsworth of Milmine, Illinois. Emma’s older sister Ann had married George Hay, a grain dealer in Milmine. Walsh then attended law school at the University of Michigan, receiving his degree in 1893. Marrying Emma had linked his future to Texas because his deceased father-in-law Enos Farnsworth, a Forty-Niner who struck it rich during the Gold Rush, had reinvested his California windfall in extensive, undeveloped land holdings in Gonzales County, Texas, leaving his young widow Susan the beneficiary of real estate that needed management. Accordingly, after finishing his studies, Walsh and his wife, along with George Hay, his wife Ann, and Susan Farnsworth all relocated to the South Texas city of Gonzales, the county seat. There, C. C. Walsh practiced law before moving north to Van Alstyne, where he and Hay organized four banks: The Farmers National Bank in 1903 (of which Walsh was the President and Hays the Cashier) followed by three smaller, state institutions in 1906, located in Tom Bean (Grayson county), Allen, and Melissa (both Collin county).

Due to Hay’s failing health, the two sold their banking interests in 1907 and moved again to the West Texas town of San Angelo, where Walsh put down roots and thereafter played a significant role in the economic development of that sheep and cattle raising region. He quickly resumed his banking career by founding the San Angelo Bank & Trust Co. in October 1907, its large $250k capital accumulated through subscriptions that Walsh solicited from area ranchers by commandeering what was the only automobile in San Angelo at the time to travel to their remote spreads.

With the founding of the Federal Reserve System, Walsh converted this institution to a federal charter in December 1914 as the Central National Bank (charter 10664) This later absorbed the Western National Bank (charter 6807) in 1919. The consolidation doubled the capital stock of the Central National, making it a major financer of the region’s economy.

As an adjunct to his banking concerns, Walsh was the moving force behind the Wool Growers Central Storage Company, a rancher-owned marketing and finance operation which he chartered in February 1909. Essentially this operated as a cooperative warehouse that enabled ranchers to pool their wool and mohair production, allowing them to better control how it was marketed and assuring them more favorable prices. It also facilitated their borrowing against the collateral of their stored supplies, for which Walsh’s Central National Bank was a convenient source of funding. More broadly, Walsh assumed a leadership role in the business community by organizing the West Texas Chamber of Commerce and serving as its president in 1923-24. He was also instrumental in bringing the new Southern Methodist University to Dallas and served as a trustee of that institution from 1912 to 1925.

Gladys, on the check (left); Gladys with her grandmother, Susan Farnsworth (center); Gladys, portrait from 1912 (right). Photo source: Ancestry.com.

As her father became influential in business and civic life, Gladys’s name began to appear in the society pages of the local newspaper. After graduating from high school in San Angelo in 1912, she was sent off for a year to Bryn Mawr College, presumably for some finishing. Upon returning she matriculated at the State University in Austin, graduating with her B.A. in 1918. Like her father, Gladys took up teaching for a time, giving instruction in science in the Austin public schools and serving as a vocational guidance director. In May 1919 she married Mark Rhey Woodward, also from San Angelo and a lieutenant in the air service of the U.S. Army.

A career officer, Woodward’s duties took them around the United States as well as to Japan, China, and Southeast Asia. Their postings included an eighteen-month stint at Fort Stotsenburg in Angeles City, Philippines, where the couple lived in a certain colonial opulence, tended by a retinue of cheap servants whose native backgrounds Gladys found pleasingly exotic. She cultivated a collector’s interest in the handicrafts of the cultures to which she was exposed, and by the time she returned home she had accumulated a trove of ceramics, embroidery, rugs, carved gemstones and the like that became the basis of a lifelong, and eventually professional, connoisseurship.

C. C. Walsh, also a collector, developed instead an enthusiasm for Texana and the cowboy culture of the American Southwest. However, unlike his daughter in her travels to exotic Asian locales, the father went completely native. Though a Texas transplant who grew up in Illinois and only arrived in the Lonestar State as an adult, Walsh became a passionate student and aficionado of the fast-disappearing folkways of the western range. Walsh had a capacity and flair for writing. Once at home in West Texas, he devoted his literary talents to producing large amounts of cowboy poetry, a highly sentimental form of verse, celebrating life on the range, that was composed in what was alleged to be the vernacular of its denizens. Prominent among Walsh’s creative output was a 1917 volume of poetry, Early Days on the Range, which featured couplets that, describing living conditions for instance, ran thus: “Thair palus wuz a blam’d ole shack / To shelter frum th’ cold / But mostly tha’ slept on th’ ground / In saddle blankets roll’d.”

Far from being considered cloying or stereotypical, such verse was prized at the time for its ethnographic exactitude. Albert Shaw’s The American Review of Reviews, a national arbiter of middle-class progressive taste, commended Walsh’s poetry as “freshly phrased melodious verse” whose “humor and pathos mingle in the lyrics together with a philosophy in which loyalty is the prime essential.” Closer to home, Walsh distributed autographed copies of the book to all of his friends, and The Texas Bankers Record assured its readers that “the book will be a lasting contribution to the literature dealing with the frontier days and the most romantic period of the great history of Texas.” As a mark of the local esteem in which he was held, at some point Walsh acquired the honorific “Colonel”, a title which he used for the rest of his life.

Walsh’s daughter Gladys had married a genuine, not an honorific, military officer, and the obligations of Lieutenant (later Major) Mark Woodward’s service took them to a number of posts during the first twenty years of their marriage. By 1925 Gladys and Mark were living in Boston, where he served as an instructor in military science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In June of that year, just as Gladys was giving birth to the first of two children, her father made yet another life transition of his own by accepting the posts of Reserve Agent and Class “C” Director at the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. At this point C. C. Walsh sold out of all his interests in San Angelo and relocated to Dallas. Walsh served in these positions and as Chairman of the Board of the bank until he retired in 1937. He died in 1943.

C.C. Walsh, mid 1920s (left); C.C. Walsh with President Calvin Coolidge and members of the West Texas Chamber of Commerce, 1926 (right).

Photo sources: Texas Bankers' Record; Library of Congress.

In his last assignment, Major Mark Woodward was the Commandant in charge of the senior cadet training school at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas. By 1938 Woodward had retired from military service and he and Gladys took up residence in nearby Gonzales, the city of her birth, tending to some of her family’s original property holdings. With a more stable residence, Gladys became involved in typical club woman activities. During World War II she was active in home-front efforts of the Texas Federation of Music Clubs.

In 1951 the couple moved to Dallas where Gladys embarked on her own career as an expert in, and legal appraiser, of art objects and antiques. The taste for collecting that she had first acquired during her early time in the Philippines developed to such a degree that, upon her death in 1970, Gladys Walsh Woodward’s estate was described by the Dallas consignment house that disposed of it in a multi-day sale as “one of the Southwest’s largest and most discriminating collections” containing “an unbelievable number of rare oriental porcelains [and] carved gemstones.”

REFERENCES

American Review of Reviews, July 1918, p. 106.

Fort Worth Star-Telegram, July 19, 1907; February 27, 1909; March 13, 1971.

San Angelo [Texas] Daily Standard, June 1, 1919; August 17, 1924 (account of Gladys’s sojourn in The Philippines).

San Angelo [Texas] Standard Times, December 21, 1943 (C.C. Walsh obit); July 5, 1953 (Emma Farnsworth Walsh obit); August 10, 1970 (Gladys Walsh Woodward obit).

San Angelo [Texas] Weekly Standard, October 17, 1919

San Angelo [Texas] Morning Times, April 5, 1933.

Texas Bankers Record, October 1917, p. 32; July 1925, p. 28.

Walsh, C. C. Early Days on the Western Range: A Pastoral Narrative (Boston: Sherman, French & Co. 1917), p. 12.

Who’s Who in Finance, Banking and Insurance: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporaries 1925-1926 (Philadelphia, PA: Julian B. Slevin Co., Inc. 1926), p. 950.

Who’s Who in the Central States 1929 (Washington, D.C.: The Mayflower Publishing Co. 1929), pp. 1021-22.