Bringing Vignettes to Life

J. Proctor Knott, Jr.

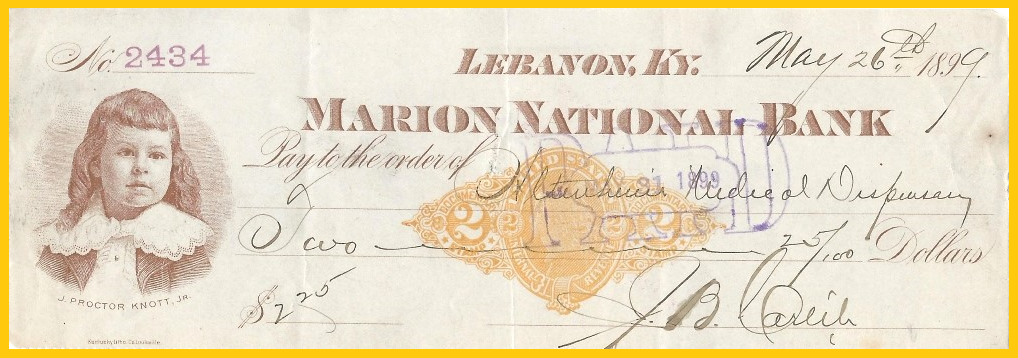

WHEN FRANCES HODGDON BURNETT'S sentimental rags-to-riches story, Little Lord Fauntleroy, was published in 1886, it ignited a craze among middle-class mothers across the United States to dress their sons up in the same confection of velvet and lace that adorned Burnett’s plucky protagonist. The vignette that appears on this check on the Marion National Bank of Lebanon, Kentucky from 1899 represents a particularly faithful example of the Fauntleroy style, down to the ringlets in the child’s long, flowing hair which, as described originally in Burnett’s book, “waved over his forehead and fell in charming love-locks on his shoulders.” In this way was the impassive adolescent visage of “J. Proctor Knott Jr.” preserved for posterity.

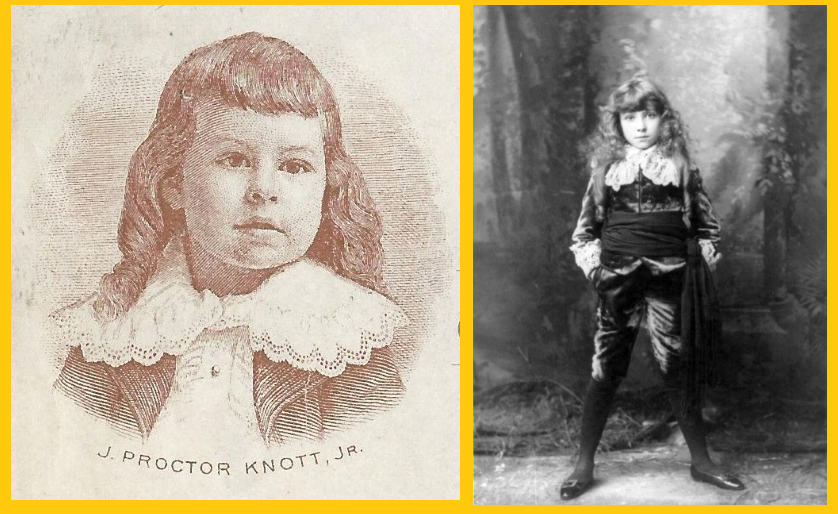

ABOVE: Joseph Proctor Knott immortalized in ruffled lace. BELOW: Joseph's portrait enlarged, contrasted with a photograph of Elsie Leslie from the 1888 Broadway adaptation of Little Lord Fauntleroy (Image sources: Author's collection; Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress).

Born in Lebanon, Kentucky, Joseph Proctor Knott (1890-1960) was the middle child of Joseph McElroy and Mattie Rubel Knott. J. M. Knott served for some twenty years as Cashier and briefly as President of the Marion National Bank (charter 2150). This bank first came to life in 1856 when the Kentucky General Assembly approved a charter for the Deposit Bank of Lebanon. By 1860, it had changed into a branch of the Commercial Bank of Kentucky and operated that way until 1874 when its President at that time, Rutherford Harrison Rountree, reorganized the bank under a national charter. J. M. Knott was the second Cashier of the bank, taking over the position from Nicholas S. Ray after the latter’s sudden death in 1885. Knott then remained at that post for the next twenty years, before assuming the Presidency for one year. In 1907 he retired from the bank to operate the Knott Lumber Company along with his oldest son, Walter.

LEFT: A $5 1882 Brown Back on the Marion National Bank of Lebanon, Kentucky, signed by J. M. Knott (Cashier) and John B. Carlisle (Vice President). RIGHT: James McElroy Knott (Image sources: Heritage Auctions; 100th Anniversary of Marion National Bank of Lebanon, Kentucky, 1956).

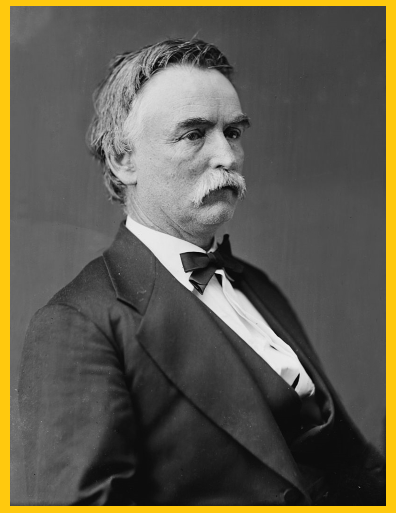

As the younger son, the “Jr.” affixed to the name of this erstwhile Fauntleroy was a bit of a conceit. Joe Proctor Knott was so designated as a nod to his great-uncle, James Proctor Knott, a prominent Kentucky politician whose career included a stint in the U.S. Congress and later service as Governor of Kentucky (1883-1887). A lawyer of considerable erudition and a celebrated raconteur who later taught at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, and established a law program there, Knott is now remembered mostly for a speech he gave before the U.S. House of Representatives in 1871. Now given the title The Untold Delights of Duluth, Knott’s oration lampooned with delirious exaggeration a proposal to give federal support to railroad construction in what were then unpopulated regions of the upper Midwest. Knott’s speech, which since been recognized as a classic of oratorical satire, earned him a great deal of good-natured notoriety, including the honor of having a city in Minnesota named after him.

Governor James Proctor Knott was only the most well-known member of what was an academically accomplished family. Governor Knott’s brother, William Thomas Knott, was a teacher and historian who wrote a history of Marion County and was later honored with a doctoral degree by Centre College. William Knott had two sons, James McElroy Knott (the banker) and William S. Knott. The latter read the law under the supervision of his famous uncle, J. Proctor Knott, and practiced law in Lebanon until moving permanently to Los Angeles in 1887.

Though Governor Knott was married twice, his first wife and their first child died in childbirth. He then took as his second wife a cousin and they did not have children. Coincidently, William S. Knott’s son, born 1886, was also named James Proctor Knott and arguably should have warranted the designation “Jr.” that was bestowed upon his cousin. However, William Knott’s departure to the west removed that branch of the family from Kentucky and the honorific went to Joseph, instead. After his term as Governor ended, J. Proctor Knott returned to his law practice and, by the early 1890s, associated himself with Centre College. He also served on the Board of Directors of the Marion National Bank from 1900 to his death in 1911. Given the ex-Governor’s connection with his nephew’s bank, for James McElroy Knott to install his son Joseph’s portrait on a check was not just a gesture of fatherly affection and family pride but probably good publicity for the bank as well.

Hon. James Proctor Knott, U.S. Congressman and 29th Governor of Kentucky. Knott was also a director of the Marion National Bank from 1900 to 1911 (Image source: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress).

Born around the time that his great-uncle began teaching at Centre College, Joe Proctor Knott had a precocious mind and shared his namesake’s taste for books. For example, in 1904 he placed an ad in the New York Times, seeking to purchase the works of the early American gothic writer Charles Brockden Brown and the German romantic E. T. W. Hoffman. Like the fictional Fauntleroy, young Joe Proctor Knott was soon sent away from his home in Lebanon, not to claim some aristocratic inheritance but to pursue a classical education. Knott studied at the Mercersburg [Pennsylvania] Academy, graduating from there as Valedictorian for the class of 1909, as well as earning awards for oratory. Thereafter he matriculated at Princeton University, graduating Magna Cum Laude and 10th out of 312 in the class of ’13 (on a visit to Washington, D.C. chaperoned by Kentucky politicians, Knott got his degree certificate autographed by a fellow Princetonian, Woodrow Wilson).

Joseph Knott spent the next twenty years as an academic nomad. After earning a Masters degree at Princeton in 1916, he took a job as instructor in Romance languages at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois. Knott stayed there through 1920, the year his brother Walter, a lumber dealer in Lebanon, died unexpectedly of heart disease (their father’s death came four years later). The following year Joseph traveled to France, where he continued his studies at the University of Montpelier. In 1922 he returned to take another instructor position, this time at the College of Wooster, in Wooster, Ohio. Knott’s position at Wooster ended in 1926, apparently because of a scandal that erupted involving another faculty member. In April 1924, Joseph Knott secretly married Florence Wallace, an instructor in Latin at Wooster. The existence of the marriage came to light only in September 1926 during divorce proceedings in which Knott was charged with having relations with other female students. The story was picked up by a number of newspapers. In the most lurid version, Knott was painted by his wife and mother-in-law as an advocate of “free love” who served as a “sweet daddy” to multiple coeds.

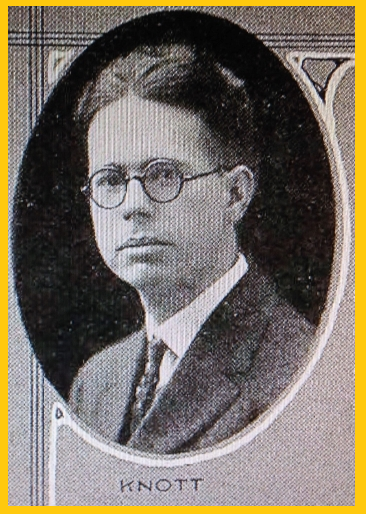

Joseph Proctor Knott in the early 1920s (Image source: Ancestry.com / Wooster College Catalog).

The weight of these accusations resulted in Knott’s termination from Wooster but did not prevent him from securing yet another post later that September as temporary head of the department of foreign languages at the Washington State College (now University) in Pullman, Washington. This lasted until 1930, when he took a position teaching French at the University of Wisconsin. At this time Knott also began working on his doctorate, which he earned in May 1933 with a dissertation entitled “The Legal Character in French Drama.” In that work, Knott explored the ways that different figures in the French legal profession-- notaires, avoués, avocats, magistrats, etc.—were portrayed across four centuries of French theatre. For the most part a formalistic and descriptive study, Knott did venture some generalizations about the evolving treatment of characters from legal officialdom. Whereas earlier French playwrights stressed the personal failings of such characters, typically falling back on caricature and stereotype, Knott contended that, by the 19th century, these portraits became infused with a greater realism. Later dramatists also proved more willing to situate legal characters and their motivations within a broader social context that explained their shortcomings as reflecting defects of law itself in its structural and systemic senses. In this way, Knott averred, French theatre reflected the changing significance of law in French society as a whole.

Acquiring the credential of a PhD promised to put Joseph Knott’s prospects for academic employment on a more even keel. Just before he completed it, however, an incident occurred that threated to upend his career. After spending the 1933 New Year’s holiday in Chicago, Knott found himself the target of what newspapers at the time called a “Badger Game.” While in Chicago Knott had been alone with another man in a hotel room. Two other men claiming to be police officers burst in and threatened Knott with exposure for allegedly engaging in sexual activity. Evidently panicked, Knott delivered to the men a check for $2,500 dollars. When the extortionists increased their demand by another $1,000, Knott summoned the courage to go to the police in Madison, who then set up a sting that resulted in the arrest one of the Chicago men when he traveled to Madison to pick up the second payment. Knott denied the very premise of the blackmail attempt and emerged from the situation with his reputation unscathed. Whether it was a matter of the authorities simply believing his story that the men’s allegation was a calumny, or perhaps a more relaxed attitude towards homosexuality in the 1930s, cannot be known. At the very least, the episode suggests a different interpretation of Knott’s brief and mysterious marriage a few years ago than what was put forth publicly in court by his estranged wife.

By then in his early forties but with his doctoral degree finally in hand, Knott quickly found a new position in the summer of 1933 in the department of Romance languages at Centre College in Danville, Kentucky, the same institution where his great uncle had held sway when Joseph was still a child. In returning to Kentucky, Joseph Proctor Knott finally found a home by moving back home. His long spell as an itinerant academic had come to an end. Knott again resided in his place of birth, Lebanon, which was some thirty miles away from Danville, living with his mother and his younger sister, Katherine, who was a music teacher in a local school. This arrangement continued after Mattie Rubel Knott’s death in 1940.

Joseph lived very much in the shadow of Governor J. Proctor Knott’s legacy. Not only was Lebanon the place where Governor Knott lived and was buried, Joseph, his mother, and sister actually resided at an address on Proctor Knott Avenue. As was noted later in his obituary, Joseph was also the steward of his namesake’s library, which amounted to some 7,000 volumes and was described as the largest private library in Kentucky. Otherwise, the Governor’s descendants in this branch of the family eschewed the example of their famous relative’s politics. In 1903, James McElroy Knott parried an attempt by local citizens to draft him as a candidate for the Kentucky senate. As a student of dramatic representations of the legal profession, Joseph ventured some tentative insights in his doctoral thesis about the relationship between the legal profession and moral character. “Sometimes it is the desire for political power which possesses [the man of the law] and his dramatists seem to suggest that there is something about politics that weakens a man’s moral fiber and renders him less resistant to temptation.” While Knott was writing about the theatre, he seems to have wanted to extend this remark beyond those confines: “one can not but speculate as to whether there is something about the practice of law—at least in the modern world—which predisposes a man to passionate weakness.”

Joseph Proctor Knott, later in life (Image source: Ancestry.com / Centre College Catalog).

If his great-uncle’s legacy was anything of a burden, it was evident that, over the next quarter century, Joseph Proctor Knott Jr. finally found his academic niche at Centre College and thrived there. A public figure active in the cultural life of his community, at the time of his unexpected death on New Year’s Day 1960 Knott was head of Centre College’s Romance languages department. Knott was widely respected for his erudition and esteemed as a teacher who upheld high standards and who also, as the local paper’s obituary put it, “had a few of the eccentricities of manner which are expected in college professors.” When Katherine Knott died in 1976, her will provided for a scholarship fund in her brother’s name that Centre College still maintains. Meanwhile, the other James Proctor Knott, Joseph’s cousin whose family had moved west before Joseph was born, experienced something of a parallel life. Initially a minister in the Church of the Nazarene, the California J. Proctor Knott later became a professor of history at Pasadena College and enjoyed an academic career that lasted about as long as his Kentucky counterpart’s.

REFERENCES

100th Anniversary, Marion National Bank of Lebanon, Kentucky, Catherine Hamilton, ed. (Transylvania Printing Co., 1956).

The (Danville, KY) Advocate-Messenger, July 26, 1933 (JPK hired at Centre College); January 3, 1960 (JPK obituary, with quote).

Burnett, Frances Hodgdon, Little Lord Fauntleroy (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1886), quote pp. 7-8.

The Capital Times (Madison, WI), January 24, 1933 (Blackmail attempt against JPK).

Chillicothe (OH) Gazette, September 11, 1922 (JPK begins teaching at Wooster College).

The (Louisville, KY) Courier-Journal, June 13, 1913 (JPK meets President Wilson).

Knott, Joseph Proctor, “The Legal Character in French Drama”, PhD diss. (University of Wisconsin, 1933)., quotes pp. 212, 214.

The Lebanon (KY) Enterprise, December 16, 1976 (Katherine Knott’s will creates scholarship fund).

The Mercersburg (PA) Journal, June 18, 1909 (JPK’s awards).

New York Times, May 28, 1904 (JPK’s classified advertisement); September 3, 1926 (JPK’s divorce case).

Princeton Alumni Weekly, April 22, 1960 (Obituary for JPK).

The (Waynesboro, PA) Record-Herald, April 7, 1909 (JPK as class Valedictorian).

The (Madison) Wisconsin State Journal, January 24, 1933 (Blackmail attempt against JPK).