Politics and Paper Money

Jane Byrne’s Rage Against the Machine

WHEN MAYOR RICHARD J. DALEY DIED a few days short of Christmas 1976, a crucial piece had failed in the workings of Chicago’s fabled political machine. While Daley himself had not created Chicago’s distinctive system of governance, he fine-tuned its operation during his decades in office in a way that both admirers and critics alike agreed made it a marvel of urban politics in the United States. Yet, just over two years after his passing, Chicago was upended by the insurgent candidacy of Jane Byrne, who was elected to be Chicago’s first female mayor in April 1979. A protégée of Daley herself, Byrne nonetheless ran as an anti-machine candidate, exploiting the weakened discipline of post-Daley politics (plus some uncommonly bad weather) to best Daley’s anointed successor, Michael Bilandic, in a narrow primary election victory. Yet the same circumstances that enabled her improbable rise also heightened the risks of her possible fall, which indeed came about in the next primary contest four years later.

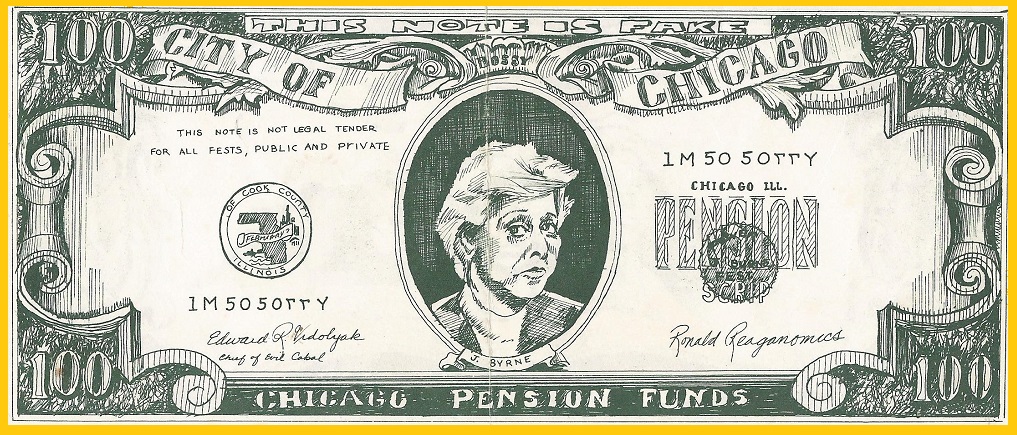

The artistically well-executed piece of anti-Byrne political scrip depicted here bears no date. Nor, unfortunately, are the identities of its designer or printer known. Most likely it circulated in late 1982 or early 1983, at the time of the Democratic Party primary campaign featuring a three-way race between Byrne, Harold Washington, and the elder Daley’s son, Richard M. Daley. Unpacking the note’s references goes some way towards framing Mayor Byrne’s significance and legacy for the broader scope of modern Chicago politics.

The Machine Logic of Chicago Politics

By the time Richard J. Daley assumed the mayor’s office in 1955, Chicago had already been controlled by Democrats for nearly a quarter century. While corruption and patronage had been a constant in Chicago under Republicans and Democrats alike, Daley created an enlightened form of the spoils system that stood out in mid-twentieth century America. Key to Daley’s success was the discipline he imposed upon players in the system, from the precinct level up. Two features in particular of Daley’s career contributed to this success. The first was his mastery of the machine, achieved through his occupying both the mayor’s office and the chairmanship of the Cook County Democratic Party. The second feature was Daley’s own personal value system. Chicago’s politics had, as a bipartisan matter, always operated on the patronage principle; it was assumed, and taken for granted, that participants’ motives were venal. Yet Daley himself was not a particularly corrupt individual in the material sense, being content with amassing and wielding power itself.

The result, for over two decades, was a particularly efficient form of urban politics. Daley presided over a triangular arrangement that balanced the patronage needs of local precinct workers and ward committeemen (the “machine” in its strict sense) with those of private economic interests (in finance, manufacturing, and construction). Those interests wanted a predictable, pro-business environment (and high municipal bond ratings) and accepted in exchange tolerable levels of corruption.

The third element was centered upon City Hall itself, where public policy in a conventional sense was made. This node of the arrangement was dominated by Daley himself. Uninterested in personal enrichment, Daley instead created a professional public administration and centralized control of the city’s budget in the mayor’s office. This enabled Daley and his party to deliver quality public services on a level that assured enduring electoral support for the Democrats, even as foot soldiers at the ward level and below were kept happy with city or county employment. For their part, all those soldiers had to do in order to keep their jobs was turn out voters on Election Day.

Taken together, these elements of Daley’s rule ensured unbroken Democratic dominance—at least as long as Daley was around. Not only did the machine consign Republicans to vestigial opposition, but any rebellions within the Democratic Party’s ranks could be quickly tamped down and neutralized. Some parts of Chicago did remain beyond machine control—notably those “lakefront liberal” wards that elected independent aldermen—but they were never powerful enough to challenge the Democratic regulars on the City Council, and Daley’s domination of that body.

As formidable as it was, Daley’s version of urban politics was beset with headwinds that became more serious as the years progressed. First and foremost, the Chicago machine was fundamentally a racist construct. Its ward politics was organized along white ethnic neighborhoods that were capable of virulent racial hostility. Consequently, the machine accommodated only with great reluctance the rising black population that came with the Great Migration. Since the 1930s blacks had been voting Democratic as part of the New Deal coalition, but in Chicago the machine gave them and their elected representatives an ungenerous piece of the action. For the most part, Chicago neighborhoods remained unabashedly segregated. Yet as the black population increased, its political representation and power in city politics did not grow in tandem. Blacks might not actually vote for a Republican, but their increasing numbers portended their importance as electoral kingmakers, if not their ability at some point to put one of their own in the mayor’s office.

A second headwind for the machine came from those interlocking trends of deindustrialization and suburbanization that had beset other American cities. As the factory jobs that black and white workers once fought over began to disappear, whites decamped to the suburbs (often to escape integrating neighborhoods) and transitioned to service-sector employment, either as commuters back into an urban core or (increasingly) within the suburbs themselves. As a result, both the economic and demographic bases of the urban machine were being eroded.

Finally, the viability of machine politics of whatever partisan sort was tested by the nationalization of American politics itself. One distinctive premise of Chicago politics was that what took place in City Hall was more important than whatever might happen in Springfield (the Illinois state capital) or, for that matter, in Washington, D.C. Yet, with the permanent expansion of the post-New Deal national government, a purely local politics became harder to sustain. If, in some fundamental sense, politics was about the control of material resources, the autonomy of local politics was threatened to the extent that national programs and their grants-in-aid supplanted the authority of municipal governments to determine the allocation of resources, whether done corruptly or not. Thus, in Daley’s world, national initiatives like Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society did promise massive benefits to cities like Chicago. But these benefits did the machine no good if their allocation were not under its control.

Jane Byrne: In, But not Of, the Machine

In the system built by Daley, Jane Margaret Byrne (1933-2014) was an anomalous figure. Her entry into public life was accidental. Widowed at a young age and with a toddler daughter, Byrne traded a probable life of mid-century domesticity for a public career, first dabbling in politics as a volunteer for John Kennedy’s 1960 campaign. This led to her acquaintance with Daley, who mentored her subsequent career, appointing her to increasingly important posts within city government that culminated in her position atop the city’s Department of Consumer Sales, Weights and Measures by 1968. Although an Irish-Catholic like Daley, Byrne hailed from the lace-curtain Sauganash neighborhood on Chicago’s north side, rather than Daley’s working-class redoubt of Bridgeport. A protégée of Daley, Byrne was nonetheless an outsider to the machine in the sense that she had not paid her dues by rising up through the electoral apparatus of ward politics.

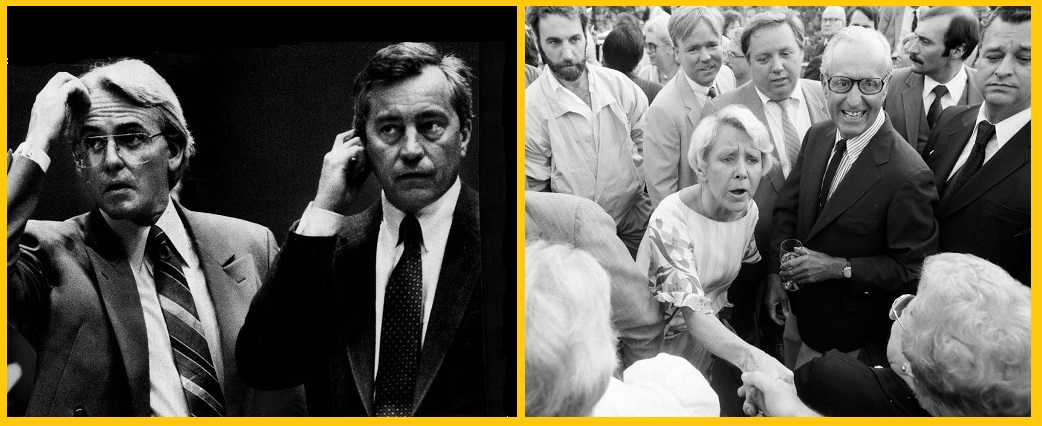

Left: Jane Byrne and Richard J. Daley. Right: Jane Byrne celebrating her 1979 Democratic primary victory. (Image sources: Crain's Chicago Business; Digital Resource Library of Illinois History.)

Byrne’s years in government prior to her mayoralty represented a genuine, and increasingly highly-paid, career. Nonetheless, Consumer Sales was basically a backwater niche within the city’s administration, and Daley’s placement of her there was fundamentally an act of tokenism, facts which would condition her later political fortunes. Responding to the political and cultural turbulence of the 1960s, Daley sought to diversify the electoral appeal of the machine to reach female voters. Byrne herself was not only a visible symbol of this effort, but she was also put in charge of organizing women within the Cook County Democratic organization, as well as representing a younger and more modern face of the Chicago machine to the national Democratic Party. That said, as Commissioner of Consumer Sales Jane Byrne was widely regarded as a hard-working and honest administrator and earned the praise of machine critics who, at least at that point in her career, saw her as a reform figure. With Daley’s approval she worked to diminish the corruption and bribe solicitation that was rife among city inspectors of grocery scales, abuses which were particularly resented in black communities.

Along with being unabashedly racist, Chicago politics of the time was also openly sexist, if not misogynist, in its values. Upon his election in 1955, Daley was exalted as “the dog with the big nuts.” The straightforward sense that politics was a man’s world was still prevalent during the Byrne era. Some of the nicknames she acquired as she rose to prominence in public life—“Calamity Jane”, “Attila the Hen”—shaded into other, more vicious, sobriquets.

The 1979 Democratic Primary Election

Byrne’s career in elective politics began as a defensive reaction to Mayor Daley’s death. With her mentor gone, Byrne’s position became precarious. Despite her high profile, Byrne had no power base or constituency within the machine, which resented her presence, disapproved of her media-friendly persona, and looked for reasons to get rid of her. After losing her position with the Cook County Democrat organization, Byrne was then fired from Consumer Sales in April 1977 by Daley’s machine-anointed successor, Michael Bilandic, in retaliation for her public opposition to a taxi fare increase. Thus cast out by the machine, Byrne turned on it as a matter of her very survival as a public figure. Her announcement in August 1977 that she would run in the next Democratic primary as an anti-machine candidate was not taken seriously.

Byrne’s triumph over Bilandic and the machine in the February 1979 primary was the great upset of modern Chicago politics. Most accounts of this episode stress the Bilandic administration’s horribly inept response to the epic snowstorm of that January, which paralyzed the city, as the decisive factor in Byrne’s victory. In addition, though, the Democratic regulars around Bilandic made serious tactical errors. Underestimating Byrne’s insurgent candidacy, they neglected to take the elementary precaution of encouraging additional, non-machine primary candidates who would split the vote to Bilandic’s advantage. Instead, Byrne was able to position herself in a two-person race as a reform candidate who would challenge what she called the “cabal of evil men” running city government.

Black voters who had already been antagonized that one of their own, alderman Wilson Frost and President pro tem of the Chicago City Council, was not chosen as interim Mayor, were then enraged at how the city’s public transport policies during the January blizzard shortchanged black neighborhoods. Some whites in northside wards, miffed that leadership positions went to southside politicians, cast their lots with Byrne as punishment (Bilandic himself had been alderman of the 11th Ward, which included Daley's Bridgeport neighborhood). Finally, Republican voters, sensing an opportunity to stick it to the machine, crossed over to cast ballots in the Democratic primary. The result, in February 1979, was a narrow but shocking (51-49%) primary victory for Byrne, a margin of some 17,000 out of 800,000 votes cast. Being a Democratic city, Chicago then gave her a thumping 82% majority in the general election, making her the first female mayor of Chicago, indeed of any major American metropolis.

Hopes that Jane Byrne would govern as a reform mayor who would take Chicago out of the machine era were quickly dashed. Much to the chagrin of the independents who supported her candidacy, Byrne quickly reconciled with her former opponents. In particular, she allied with two notable figures— the aldermen Edward Burke and Edward (“fast Eddie”) Vrdolyak—who epitomized the very “evil cabal” that she had inveighed against during her campaign. Byrne’s pact with Vrdolyak (whose pretend signature appears on the front of the anti-Byrne note) was especially galling to reformers. Not only had Vrdolyak represented the interests of the taxi companies whose fare increase plans got Byrne fired in the first place, he had also served as Bilandic’s campaign manager during the Democratic primary. Now that she was Mayor, Byrne turned to Vrdolyak to manage the City Council on her behalf. In her defense (or at least by way of explanation), it was unrealistic to expect that the electoral coalition that put her in office—blacks, independents, disaffected northside whites—would be the same coalition that would enable her to govern once in office. The Chicago political machine had been chastened and weakened by her victory, but it was still there as a fact of life. Once in office herself, Byrne had to accommodate the machine and its priorities, even as she sought to impose her will upon it.

Left: The two Edwards, Burke (l) and Vrdolyak (r). Right: Jane Byrne with her husband, Jay McMullen. (Image sources: michaelklonsky.blogspot.com; Chicago History Museum.)

Other problems facing Mayor Byrne were more of the self-inflicted variety. The same aggressive media style that worked well during her campaign did not translate easily into governance. Critics attributed some of the problem to the Svengali-like influence of her second husband, Jay McMullen, a newspaperman whom she had married in 1978 and who served as her adviser. Likewise, having run against the machine yet trying to govern with it contributed to high personnel turnover in the mayor’s office. By one count, in her first year alone Mayor Byrne went through two deputy mayors, three press secretaries, and four police superintendents. A recurring theme of this turmoil was her questioning of the loyalty of administrative holdovers from the Daley/Bilandic era. Unlike Daley, Byrne was never able to assemble a team of top administrators whom she felt she could trust. The cumulative effect of this ambivalence, after four years, was exhausting for her supporters and opponents alike.

Even a figure with a steadier hand than Byrne would have found governing Chicago in the late 1970s a daunting experience. Mayor Byrne inherited a parlous fiscal situation that resulted from years of accumulated cronyism in municipal finance. ‘Handshake’ agreements typical of the Daley era had been enough to secure peace with the city’s labor unions. With Daley gone, that cronyism was replaced by a much more arms-length and contentious relationship between Chicago and its workers. The more inflationary conditions of the late 1970s also revealed how unsustainable some of those wage agreements had become. Byrne gained credibility as a fiscal conservative by facing down strikes by teachers, sanitation workers, and firefighters. Her administration also stabilized the city’s finances and shored up its all-important bond rating. The appearance of “Ronald Reaganomics” on the scrip note’s front may be an oblique gesture to her stance on budget issues.

Byrne’s mayoralty acquired a more positive gloss through her civic boosterism and promotion of the arts. Although it was begun under Bilandic, Byrne became identified with a musical extravaganza known as ChicagoFest. Her administration promoted it and other knock-off events (Jazz Fest, Blues Fest), as well as Taste of Chicago, all of which Byrne claimed would enhance civic life—or, according to her critics, would beguile the voters with bread and circuses. The scrip note’s claim to being “not legal tender for all fests, public and private” is a swipe at Byrne’s patronage of these events [Full authorial disclosure: as a college student in Chicago at the time, I benefited from Byrne’s policies by attending an Alice Cooper concert in 1980 at Navy Pier, a performance that included Cooper tossing dismembered baby dolls into the audience]. Byrne’s sense of public flair also included welcoming film makers to use her city as a set, with one notable result being The Blues Brothers (1980), much of which was filmed in and around Chicago in the summer and fall of 1979.

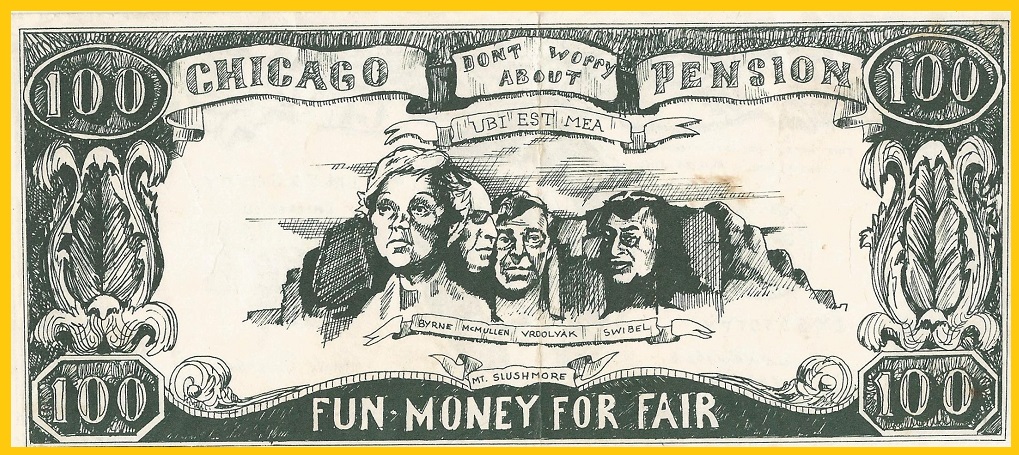

As Jane Byrne geared up to run for a second term in 1983, the accumulating grievances concerning her chaotic governing style assured a competitive Democratic primary. Most of the case against Byrne’s re-election is developed on the back of the scrip note, which stresses themes of corruption. Above a caricatured rendition of “Mount Slushmore” is a banner with the phrase “Ubi Est Mea”. This bit of faux Latin, meant to translate as “Where’s Mine”, was coined back in a 1967 newspaper column by the longtime Chicago journalist Mike Royko. Something of a professional cynic, Royko proposed this phrase as a substitute for Chicago’s official motto, “Urbs in Horto” (City in a Garden), in recognition of the prevalence of graft in city government.

Beneath that banner, the three busts alongside of Byrne represent the malign influences that critics alleged had spoiled city government. Next to Byrne is her husband Jay McMullen, then Edward Vrdolyak, and finally Charles Swibel, a prominent property developer and longtime head of the Chicago Housing Authority until he was forced to step down in 1982 over corruption charges. Through Swibel’s friendship with McMullen he became close to Byrne, serving as an advisor and her campaign fundraiser for the 1983 election. While it would now seem like an unremarkable aspect of electoral politics, Byrne’s opponents (and particularly her mentor’s son, Richard M. Daley) took her to task for the sheer size of her campaign war chest. A holdover from the Daley era, Swibel stood for everything that reformers found bad about Chicago politics. His dubious reputation did damage to Byrne’s public image.

An editorial cartoon from 1983 by Jack Higgins of the Chicago Sun-Times attacking her fundraising record.

The most sustained attack made on the back of the scrip note is also the most obscure. The references on both sides of the note to “Chicago Pension” as well as the phrase “Fun Money for Fair” on the back relate not to any of the various festivals that Byrne was sponsoring, but to Chicago’s ill-starred application to host the 1992 World’s Fair. Pitched as a celebration of the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s voyage to the Western Hemisphere, siting the World’s Fair in Chicago would have entailed a massive transformation of its lakefront. In keeping with her belief that the city benefited from the infrastructure and real estate development catalyzed by such public events, Byrne boosted Chicago’s application to host a World’s Fair (later, in her memoir My Chicago, Byrne wrote fondly about Chicago being the venue for both the Columbian Exposition of 1893 and the 1933 World’s Fair).

Byrne’s aspirations for a Chicago World’s Fair did not last much beyond her mayoralty, as her successor Harold Washington took a dim view of its developmental priorities. In the 1983 election, pending plans for a World Fair became a line of political attack against Byrne when it was alleged that she planned to raid the pension funds of city workers in order to finance land purchases that the World’s Fair would have necessitated (hence the text on the note). While no evidence ever emerged for this allegation, it did come at a time when reforms were being considered that would have consolidated the management of Chicago’s four municipal pension under one authority. At that time, Illinois state law had recently loosened the legal restrictions imposed upon the funds’ management. In addition, further proposals endorsed by a Byrne-appointed commission envisioned a portion of the pension funds’ resources being allocated for venture capital and housing investments. In this setting, fears of political interference in pension investment decisions fell upon receptive ears.

The End of the Brief Byrne Era

Whatever the shortcomings of her administration, Mayor Jane Byrne’s electoral loss can be seen as a straightforward consequence of the shift in the black vote towards one of their own, Harold Washington. In 1983’s three-way primary race, Byrne came in second, with Richard M. Daley a close third. Had Byrne maintained better relations with black voters she would have likely served a second term. However, the same loosening of the machine’s control that enabled her 1979 candidacy also empowered African Americans to finally flex their political muscle. Another way of looking at that 1983 contest was that, if the younger Daley hadn’t entered the race as a spoiler, Byrne’s incumbency advantage might have ensured her re-election. While Byrne disappointed many and created strong negative feelings in others, her political nemesis had always been Richard M. Daley who, upon achieving the mayoralty later himself, went on to treat Byrne’s legacy in a vindictive and shabby way.

That Byrne’s first victory was no fluke was shown in the 1987 primary when, despite losing again, she nonetheless put in a credible performance against Harold Washington in a two-way race. Even more than in 1983, African Americans voted in a bloc for Washington. However, by the 1991 primary it was clear that her chances (and her campaign fundraising powers) had dwindled, making that contest her last attempt at public office in her political career.

..........

REFERENCES

Byrne, Jane. My Chicago (New York: W. W. Norton 1992).

Chicago Tribune, January 11, 1983; January 23, 1983; March 9, 1983.

Gale, Neil. "The Biography of Jane Byrne, Chicago's First Female Mayor" Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal (February 28, 2019). https://drloihjournal.blogspot.com/2019/02/the-biography-of-jane-byrne-chicagos-first-and-only-female-mayor.html

Granger, Lori and Bill. Fighting Jane: Mayor Jane Byrne and the Chicago Machine (New York: The Dial Press 1980), esp. ch. 22.

Holli, Melvin G. "Jane M. Byrne: To Think the Unthinkable and Do the Undoable" in The Mayors: The Chicago Political Tradition. Edited by Paul M. Green and Melvin G. Holli, 3rd ed. (Southern Illinois University Press 2005), pp. 168-178.

Rakove, Milton. "Jane Byrne and the New Chicago Politics" in After Daley: Chicago Politics in Transition. Edited by Samuel K. Gove and Louis H. Masotti (University of Illinois Press 1982). pp. 217-235.