Bringing Vignettes to Life

JG Cocking’s Tea Check

An Introduction to the Tea Check

As a vehicle for premium marketing, the “tea check” has been overshadowed by the more extensive coupon and certificate circulations issued in the early 20th century by outfits like the United Cigar Stores and the Mutual-Profit Coupon Corporation. Unlike those latter circulations, tea checks were relatively simple affairs. Used by specialty retail merchants to promote the sale of coffee, spices, flavorings, extracts, and (of course) tea, these checks did not resemble currency in the ways other premium certificates might. Typically, tea checks were much smaller in size, lacked any denominational range, and were printed without elaborate ornamentation. Nonetheless, as with other premium schemes, shoppers were encouraged to accumulate tea checks which they could redeem in varying quantities for a selection of gifts (crockery was a typical favorite) either advertised in a premium catalog or simply made available at the shoppers’ stores.

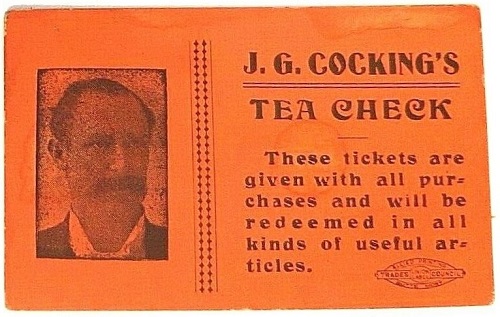

J.G. Cocking’s Tea Check, pictured here with considerable enlargement, is itself an even more minimal version of that humble coupon. Like other coupons of this kind, it measured only 1 ½” by 2 ½.” Other than a slightly-glowering portrait of the proprietor, along with the brief promise that “these tickets are given with all purchases and will redeemed in all kinds of useful articles,” the tea check lacked any further advice or identifying information on either front or back, other than a union bug sourcing it to Butte, Montana. Whoever received such a tea check knew who J.G. Cocking was and needed no instructions about how to redeem it

.

Tea check issued by James Goldsworthy Cocking of Butte, Montana, between 1908 and 1917 (Source: eBay).

Origins of the Tea Check

While the use of the “tea check” in these ways had its origins in British retail trade, the earliest American example appears to have been those issued by John W. Macfarlane, owner of the Chicago Tea Company, in the early 1870s. Macfarlane, a Scottish immigrant, employed tea checks as a marketing tool as he expanded his stores across that city. Another example was King's Tea Stores of Detroit, which offered premiums by tea check redemption in 1879. The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company, which was beginning to develop a national chain during this decade, was also an early adopter.

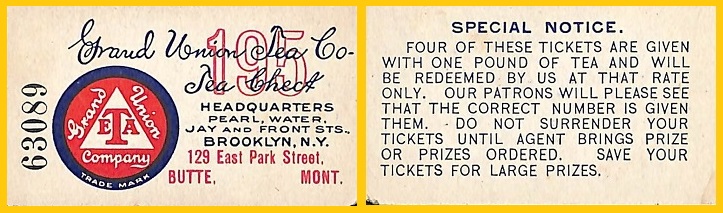

However, by far the most common kind of tea checks in circulation were those issued by the Grand Union Tea Company. Like Great Atlantic and Pacific, Grand Union began as a specialty retailer that developed into a more general-purpose grocery chain by the early 20th century. Founded by three brothers in Scranton, Pennsylvania in 1872, Grand Union relocated to Brooklyn, New York by the end of the century, where it established an immense warehouse to serve the national market. Initially, Grand Union marketed its products directly to customers door-to-door, bypassing established merchants. As it built out its own chain of specialty stores, first in Scranton and then nationally, Grand Union expanded first by hiring agents in new areas to handle its product lines; then, if local demand warranted it, the company would open up a more permanent storefront under its direct management. As the company expanded, so did the use of tea checks as premium coupons, often printed with the names of the local stores that issued them. This was how the company came to establish its presence in Butte, Montana.

Tea check issued by the Grand Union Tea Company Store in Butte, Montana, sometime after 1908. When Grand Union opened the store, J.G. Cocking resigned his agency, setting up his own tea business.

Hocking & Cocking: Tea Merchants of Butte, Montana

Francis (Frank) William Hocking (1859-1918) and James Goldsworthy Cocking (1866-1941) both came to the United States in the same immigrant stream that brought settlers from Cornwall County, England during the late 19th century. With the collapse of the Cornish copper mining industry in the 1860s, migrants sought similar employment in extractive industries in the United States and elsewhere. Hocking, born in Camborne, England, arrived in the United States as a child and grew up in Nevadaville, Colorado, where he worked as a miner like his father. Cocking, born in Truro, emigrated in 1884 after the death of his father, first spending a few years in California before moving to Butte, Montana in 1889, where he lived with his mother and two sisters (other relatives of Cocking, and at least a third sister, found their way to the Copper Belt in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, another center of Cornish migration). While at that time Butte was world famous for its copper production, there is no evidence that Cocking himself never worked in the mines, although another unrelated namesake, James Cocking, was both a miner and active in the labor movement there. Instead, in the early 1890s Cocking pursued a commercial course of study at Butte’s newly established Newill Academy (later renamed Silver Bow College).

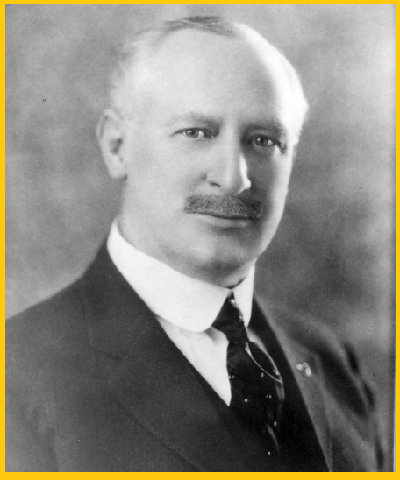

A formal portrait of James. G. Cocking, probably dating from his time as Mayor of Butte (Source: Butte-Silver Bow Public Archives).

Frank Hocking's and James Cocking’s tea collaboration—there were no signs of a formal partnership, nor was it clear which one was in charge of the business—came about shortly after Frank married one of James’s sisters, Emma, in 1896. Early the next year “Hocking & Cocking” placed newspaper advertising to hire agents on behalf of the Grand Union Tea Company. Henceforth both men were mentioned in Butte newspapers and listed in city directories as being in the tea business and being associated with Grand Union; each man operated out of nearly adjacent home addresses on Colorado Street. After his mother died in 1901, Cocking kept the family residence for the rest of his life.

In addition to the tea business, thanks to some astute real estate speculation, James Cocking prospered. By 1908 Grand Union decided to open a store in Butte, but under outside management. Turning down an offer to become a salaried employee of the new store, Cocking instead maintained his own tea business which he continued to run out of his residence between 1908 and 1917, years when J.G. Cocking’s Tea Checks would have made their appearance. For his part, James’s brother-in-law Frank bought an existing grocery concern in 1913, becoming his own proprietor. The next year, at the age of 48, Cocking married a recent divorcée, May Mendenhall (née Dalton); together they had one daughter.

J. G. Cocking in Public Life, and Mayor of Butte

Thanks in part to the fleet of delivery wagons with which he conducted his trade, the name of James G. Cocking became familiar to Butte residents. In addition, Cocking was active in fraternal orders, in particular Silver Bow Lodge 48 of the A.F. & A.M. He was also a 33rd Degree Mason under the Scottish Rite. Outside of that world, however, he took a more diffident approach to public service. Part of the reason may well have been his political affiliation. Cocking was a lifelong Republican in a heavily Democratic and Socialist-inflected city. In addition, he was a consistent proponent of temperance and a foe of gambling, two positions that might not have endeared him to the broader population of that rough mining town.

Cocking’s first attempt at public office came in 1916, when he ran unsuccessfully to be alderman of Butte’s Eighth Ward. In 1918 Frank Hocking succumbed to the influenza wave of that year. Some time after the death of his brother-in-law, Cocking retired permanently from the retail trade and could devote himself more to public life. His political fortunes improved considerably in April 1921, when he beat the incumbent Republican mayor in his party’s primary (coincidently, the sitting mayor also hailed from Cornwall) and went on to win the general election the next month.

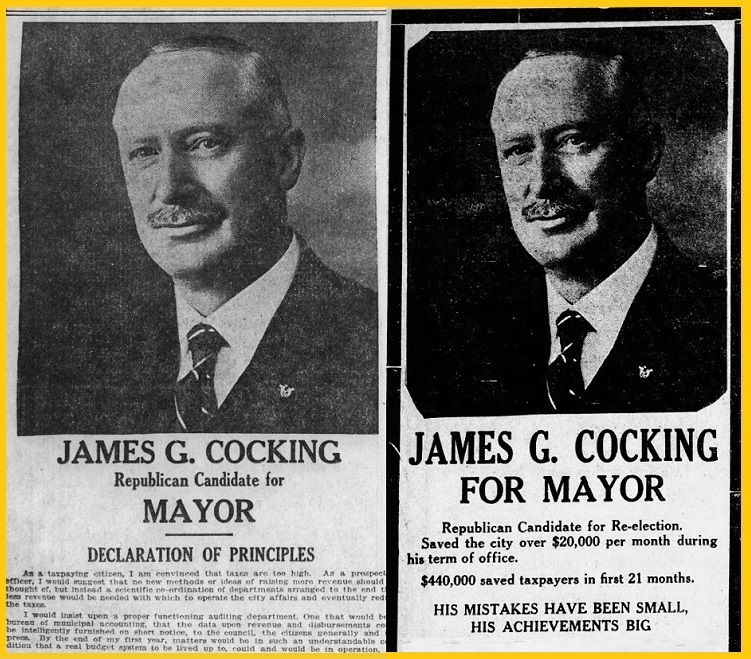

Despite some last-minute, and very improbable, insinuations by a local newspaper that Cocking had made a secret deal for support from the local branch of the Wobblies to fill city hall with “swarms of loafers and parasites,” Cocking conducted his administration in a conventionally Republican fashion. Indeed, Cocking’s rhetoric not only stressed the typical businessman’s preference for lower taxes but reflected the earnest Progressive (in the early 20th century sense) conviction that government could and should be run on a scientific basis. Cocking’s somewhat verbose list of “principles” (truncated in the image below) encapsulated the prevailing ‘good-government’ orthodoxy, including his belief that the city’s aldermanic system should be eliminated, Butte City and Silver Bow County governments be consolidated, and the very office he was running for—mayor—should be abolished (all of Cocking’s wishes were eventually granted, very posthumously, in 1977).

Campaign advertisements published by James G. Cocking's mayoral campaign, 1921, left, and 1923, right. (Source: The Butte Miner, March 6 1921; March 18, 1923).

If Cocking’s ideas about institutional reform were a bit utopian for the time, his governing style was much more concrete. Not only did Cocking issue platitudes about efficiency, economy and businesslike practices, he actually carried out his promises through salary and staff reduction measures, targeting especially law enforcement. Cocking’s ‘defund the police’ approach to fiscal retrenchment generated some pushback by those employees affected, many of whom were Irish. In November 1921, Mayor Cocking further antagonized that constituency by using an anti-loitering ordinance to break up a Fenian picketing and boycott campaign directed at a local grocery chain, Luteys Stores, for its refusal to buy Irish Bonds or to refrain from selling English goods (including tea, the newspapers pointed out) Although this firm stance against Irish Catholics attracted approving notice from Cocking’s national Scottish Rite Masonic organization, which generally viewed them as a papist pestilence, it was risky from a local political point of view. National prohibition, which had gone into effect the previous year, was also enforced locally under Cocking’s administration. Likewise, Cocking launched campaigns against gambling, cracking down on “Chinese lottery” machines (a form of Keno), card games, and baseball pools, the last being a popular pastime among Butte residents. Cocking pursued public uplift basically by hectoring Butte’s long-serving police chief, Jere Murphy, through press releases demanding that Murphy enforce the existing laws on the books, helpfully citing and quoting extensively from those statutes for Murphy’s benefit.

From a fiscal standpoint at least, Cocking’s mayoralty was a clear success. The savings he wrung out of public payrolls enabled the city to issue bonds that cleaned up the arrears which had made its warrants cashable only at a considerable discount. This enabled city government to once again operate on a cash basis. In his 1923 re-election campaign, Cocking claimed savings of $440,000 in city expenditures. Alas, this record and the claim it inspired— “His mistakes have been small, his achievements big,” which sounded more like a tombstone epitaph than a campaign slogan—were not enough to keep the public from turning him out in favor of his Democratic opponent.

Cocking made one more unsuccessful attempt at the mayor’s office in the 1925 race, promising if elected to “exercise economy” and “protect the youth from debauchery, shame and crime.” Whatever the public understood by those words, it was not what they wanted. Thereafter James G. Cocking retired from public life as well as from business, devoting himself to the affairs of various fraternal orders affiliated with Freemasonry, achieving the distinguished rank of Past Master in several of them. He passed away in December 1941 in the same family residence at 501 Colorado Street at the age of 75.

..........

REFERENCES

Ancestry.com, for sundry and relevant census records, marriage and death certificates, and city directories.

Andreas, Alfred Theodore, History of Chicago, Vol III (Chicago, IL: A. T. Andreas Co., 1886), p. 350.

The Anaconda (Montana) Standard, October 14, 1892; February 28, 1897; May 14, 1901; March 5, 1916; December 1, 1918; April 3, April 10 [profile of JGC], June 12, 1921; June 16, 1922; February 21, 1925.

The Butte (Montana) Miner, March 11, 1908; September 6, 1913; March 6, April 5, May 6, May 25, 1921; June 20, 1922; March 18, April 21, 1923.

Daily Inter Mountain (Butte, MT), May 9, 1899.

Detroit Free Press, September 21, 1879.

The (Butte) Montana Standard, December 24, 1941 [JGC obituary].

Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Stephan Thernstrom, Ann Orlov, and Oscar Handlin, eds. (Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press 1980), pp. 243-245.

The New Age Magazine (Washington, D.C.), January 1922, pp. 31-33.

Scranton (Pennsylvania) Tribune, December 8, 1883.