Bringing Vignettes to Life

Joseph D. Clapp, Lucien B. Caswell, and Early Banking in Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin

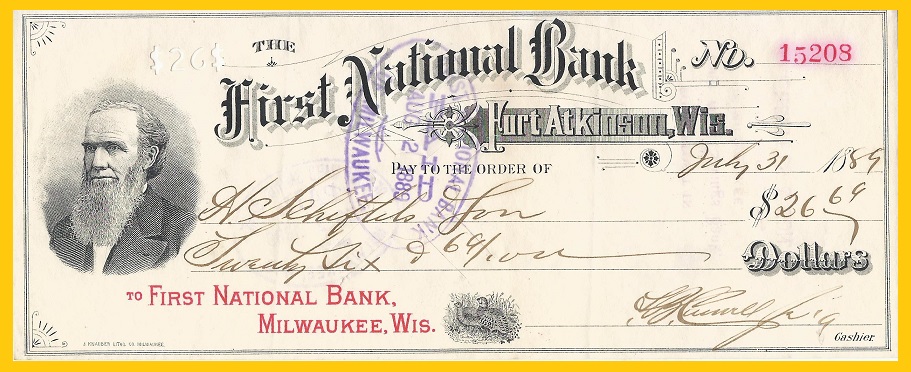

WHEN JOSEPH D. CLAPP'S PORTRAIT began appearing in the late 1880s on drafts drawn on the First National Bank of Fort Atkinson, he had been President of that Wisconsin institution for nearly twenty-five years since its founding in 1864. While not the first national bank to open its doors in Wisconsin, it was one of the earliest to take advantage of the new federal banking law and represented one of several astute business moves taken by Clapp and his long-time partner, Lucien B. Caswell. Both transplants from Vermont, Clapp and Caswell developed a relationship characterized by entwined business and family connections that would extend through the end of the century. Honoring Clapp in this way not only acknowledged his long service to the bank but also his status as one of the original settlers of Jefferson County, Wisconsin.

A Draft on the FNB of Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin (Charter 157), signed by Lucien B. Caswell Jr., Assistant Cashier. (Image source: author's collection)

Joseph Dorr Clapp (1811-1900) was born in Westminster, Vermont. He lived there and in Boston until 1839 when, upon the death of his father, Joseph and his older brother Mark moved to the newly-formed Jefferson County in Wisconsin Territory, part of a migration of New England settlers into that portion of the original lands of the Northwest Ordinance. The two brothers settled on land in what later became the town of Milford and farmed there for the next 18 years. In 1841 Joseph married Zida Ann May, daughter of Chester May of Fort Atkinson. It is doubtful if they had any biological children. In a mysterious 1845 petition to the territorial legislature, Clapp did claim parentage of an illegitimate child, Edward Livingston Clapp, for whom he unsuccessfully sought legislative dispensation to make his legal heir. Listed as a part of the Clapp household with his birthplace as Vermont in the Census of 1850, the young man died in 1859 of typhoid fever. By that time, Joseph Clapp had retired from farming and moved to Fort Atkinson, where at middle age he turned to a variety of non-farming pursuits, most notably banking.

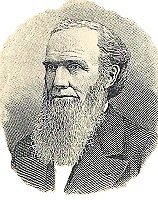

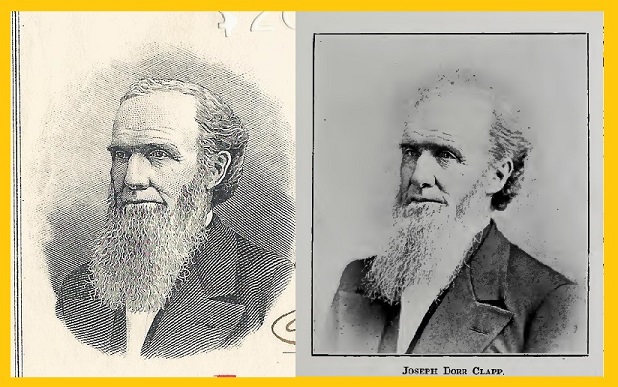

J.D. Clapp's image on the bank draft, and from Biographical Sketches (1899)

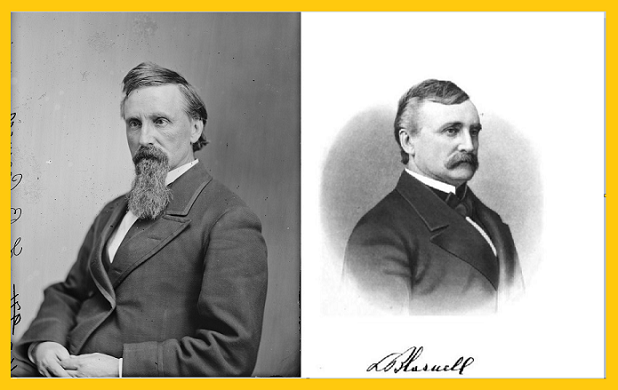

This second stage of Clapp’s life was marked by an enduring personal and business relationship with a younger colleague, Lucien Beal (or Bonaparte) Caswell (1827-1919). Caswell was born in Swanton, Vermont and relocated with his family to Rock County, Wisconsin in 1837. After some college education and reading of the law, Caswell gained admission to the bar in 1851 and moved to Fort Atkinson the following year, where he began his legal practice. By 1854 Caswell was serving as District Attorney of Jefferson County and soon embarked upon a long career in politics. At about this time he also assumed a lifelong tenure on a local school board, which occasioned his acquaintance with Chester May’s other daughter, Elizabeth Hannah, who happened to be a teacher. Lucien and Elizabeth married in 1855. This union made Joseph Clapp and Lucien Caswell brothers-in-law, a connection that became the basis for a number of business ventures which, over the decades, linked the fortunes of Clapp with the Caswell and May families.

Lucien Beal (or Bonaparte) Caswell, as a young man (left), and as a older and stouter politician (right). (Image sources: Library of Congress; Usher (1914).

The Brief, Unhappy Life of the Koshkonong Bank

The first of Clapp’s and Caswell’s ventures was the establishment of the Koshkonong Bank. Fort Atkinson’s first financial institution, the bank was founded in early 1859 with Clapp as President and Caswell as Cashier, the two men contributing equal shares of the bank’s $25,000 capital. The Koshkonong Bank was a relative latecomer in the flood of institutions uncorked by Wisconsin’s free banking law of 1852. More permissive in its regulation than other free-banking states at the time, Wisconsin allowed banks to issue currency up to 100% of the par value of bonds deposited as collateral with the state Comptroller (up until 1858, riskier railroad securities could be part of this collateral). In lieu of (and as a substitute for) specie reserves, stockholders were also required to give, as an additional security, their personal bonds to the amount of 25% of their banks’ note circulations.

Prior to 1852, banking had simply been illegal in Wisconsin, so the subsequent, spectacular growth in the number of banks and their circulation started from a minimal base. Nonetheless, between 1856 and 1859 alone, the number of banks in the state more than tripled, and their banknote circulations grew fourfold. Notable in this growth was the establishment of institutions in remote areas of northern Wisconsin with no population; these were the notorious “wildcat” banks that did little loan or discount business, existing instead simply to puff their notes into circulation at great distances and with great difficulty of specie redemption.

The Panic of 1857 shook Wisconsin banking, but did not bring about a general collapse of its institutions. Far more threatening, however, were the gathering clouds of the Civil War. Wisconsin’s free-banking law required deposited bonds to bear a minimum of six percent interest, which had the effect of encouraging bankers to load up on the dodgier paper of southern states, which by 1860 comprised some two-thirds of Wisconsin currency’s bond backing. Yet the growing threat of secession would soon send the price of these bonds spiraling downward, throwing the state’s financial system into disarray.

Luckily for Clapp and Caswell, shortly after opening the Koshkonong bank the two partners were able to sell their stakes in December 1859, before the bottom dropped out of the bond market. The purchaser of their bank was Abraham H. Van Norstrand, a physician with a practice in the nearby city of Jefferson, the seat of the eponymous county. A native of Poughkeepsie, New York who had moved to Wisconsin in 1847, Dr. Van Norstrand coincidently had his own connection with Vermont—he had taken his medical training there. A restless man with a taste for more wealth than ministering to the sick could provide, Van Norstrand first whetted his financial appetite with a successful speculation on the depressed bonds of the Wisconsin Marine and Fire Insurance Company. In 1851 he entered politics by winning a seat in the State Assembly as a Democrat, where he was a supporter of Wisconsin’s free banking law. After losing re-election in 1856 (a year that Caswell was also an unsuccessful candidate), Van Norstrand dabbled in mercantile and insurance pursuits and, when the Bank of Jefferson opened its doors in November 1858, became its first Cashier.

Located just a few miles north of Fort Atkinson, the Bank of Jefferson was a natural competitor to the Koshkonong Bank. Neither institution really fit the stereotype of the “wildcat” bank operating at some remote location so as to avoid redeeming its banknotes. Yet the relatively easy terms of Wisconsin’s free banking law—especially those pertaining to bond backing—rendered the entire structure of the state’s banking system vulnerable in the face of the approaching storm.

The generous returns to banking in early Wisconsin made it attractive to anyone with a taste for risk. Speculators could buy the requisite 6% bonds of some southern state at a hefty discount (reflecting their uncertain character), yet receive 100% of the par value of the bonds in the form of crisp Wisconsin banknotes. This new currency, which might trade at a smaller rate of discount in New York than did the underlying bond collateral itself, could then be used to purchase a new round of bonds, and the process repeated. Alternately, the fresh supplies of currency could simply be disbursed as loans in the community, with the financier being doubly rewarded: first by clipping the coupons on his bond collateral, and second by receiving the interest paid on his loan of currency. Either way, banking on those terms seemed like a lucrative proposition, and Dr. Van Norstrand took the bait. Now owner of his own bank, Van Norstrand quit his relationship with the Bank of Jefferson and hired his father-in-law, George Hebard, to be the Koshkonong Bank’s Cashier.

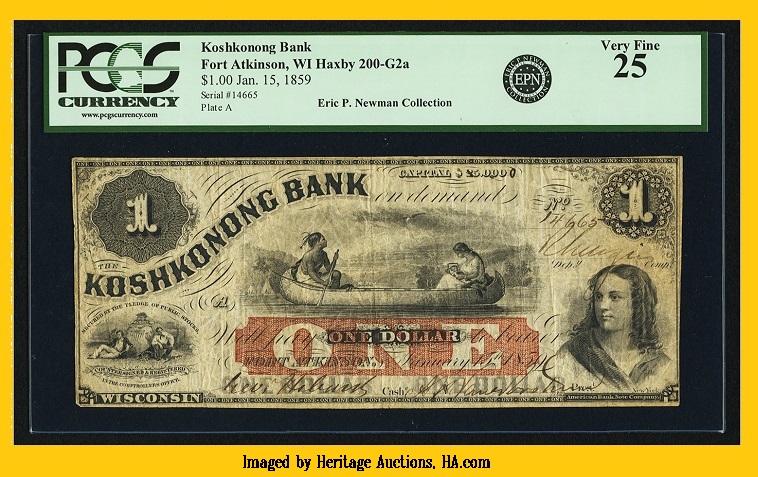

A $1 note on the Koshkonong Bank, signed by George Hebard, Cashier, and Abraham Van Norstand, President (Image source: Heritage Auctions).

The change in ownership of the Koshkonong Bank in late 1859 reflected, in a single transaction, two basic wagers on the political direction of the country. Though a Democrat, Joseph Clapp’s opposition to slavery put him in the “war” faction of his party. Lucien Caswell had also begun his political career as a Democrat, but switched his allegiance after losing his election to the State Assembly in 1856, a move that was politically astute but undoubtedly sincere, as he went on to serve as a stalwart Republican for the rest of his public career. Both men saw a war of secession as increasingly likely, and sought to trim their financial exposure to it.

In contrast, Van Norstrand, also a Democrat but a supporter of Stephen A. Douglas, was of a more optimistic mien. He viewed the acquisition of the Koshkonong Bank as his opportunity to get into the game at a good price. As Caswell recalled later of this episode, “Dr. Van Norstrand wanted our bank, and we wanted he should have it, so we sold it to him.” Indeed, the bank’s new owner promptly doubled the amount of bonds on deposit with the State Comptroller, with an eye to increasing the bank’s note circulation.

The single largest portion of the Koshkonong Bank’s note collateral consisted of Missouri 6’s (not South Carolina bonds, as Caswell’s memoir has it) and this state’s paper also comprised the single largest holding of all the southern securities that made up the bulk of Wisconsin banks’ bond deposits. The year 1860 brought a sustained erosion in the price of these securities, especially as it became likely that Lincoln would win the Presidency and southern states would secede. Towards the end of that year the Comptroller imposed two deficiency levies on the state banks in response to the declining value of their collateral; an impending third call in February 1861 was delayed by the Assembly out of fear that most Wisconsin banks would fail if it were imposed.

Van Norstrand sweated out his investment in the Koshkonong Bank in the face of falling bond prices and deficiency levies through most of 1860. By early November 1860, as the election of Abraham Lincoln made secession well-nigh inevitable, his Wisconsin namesake sought a way out of the financial trap with an ethically-dubious plan. Van Norstrand notified the Comptroller that he was looking to sell his bank, and at the end of the month presented a willing but naïve buyer by the name of Isaac Savage, a local farmer. Van Norstrand contrived to transfer legal title to the bank over to Savage so that Van Norstrand could swap out his personal bond on file with the Comptroller’s office with Savage’s own (this was the bond, required by law, that made him personally responsible for a quarter of the value of the bank’s circulation). This switch of bonds was filed on December 7, 1860. In this way Van Norstrand sought to apply the Hippocratic Oath to his own dwindling personal net worth. That Savage was actually a straw man was apparent by the fact that Van Norstrand continued to run the bank himself. Indeed, in February 1861 he secured permission from the State Assembly to relocate the bank to Jefferson, where he operated it with his father-in-law out of his own medical offices. By late March, the bank’s situation had deteriorated sufficiently that newspaper reports began advising the public against accepting notes of the bank.

When newspapers got wind of the ownership change, the cry arose that Savage was an irresponsible bondsman merely fronting for Van Norstrand. An investigatory committee of the Wisconsin Senate demanded an explanation from the Comptroller as to how he could have approved of such a switch. The Comptroller countered that there was no reason to think that Van Norstrand’s sale to Savage wasn’t legitimate, and that the law allowed the withdrawal of one bond and the substitution of the other. In any case, Savage had reported a sufficient net worth to make his bond acceptable.

In the end this gambit did not spare Van Norstrand from the financial consequences of his ill-timed investment. Running out of specie to meet banknote redemptions, the Koshkonong Bank suspended payments on April 2, 1861. The next month, its bond collateral was auctioned off per the law by the Comptroller at fire sale prices, netting just 54 ¾ cents for every paper dollar of the bank outstanding. This coincided with a slump in the quoted price of Missouri 6’s, which fell in just a month from 60 to under 40. The Koshkonong Bank was no more.

Decades later, the demise of the Koshkonong Bank would gain a bit of historical notoriety in the hands of financial pundits like Charles Conant, who cited the bank’s experiences in editions of his book on American banking as being emblematic of the evils of “wildcat” era. Again, this characterization was not entirely fair. For one, there were banks wound up whose collateral sales produced even worse results than the Koshkonong’s. In terms of both bank capitalization and note circulation per capita, Jefferson County was hardly overbanked, compared to other parts of the state. Unlike the truly fraudulent institutions, the Koshkonong Bank was doing a genuine business, albeit under an imprudent regulatory regime.

In any event, Van Norstrand and the Koshkonong Bank were swept away even before the worst of the storm hit Wisconsin banking. Despite legislative opposition, the Comptroller issued a third call for a depreciation levy in April 1861, which was widely ignored by the state’s banks. Under the law, the Comptroller was required to auction off the collateral of the noncompliant banks, but this would have only accelerated the collapse in bond prices and imploded the entire banking system. At this point the legislature stepped in to suspend the requirement of specie payments, giving the banks breathing space long enough that a plan could be crafted whereby the impaired southern bond backing could be replaced by better securities.

This restructuring was hardly a painless, or even a peaceful, process. Between January 1861 and early 1862 Wisconsin’s banknote circulation contracted by over half; bank capital per capita shriveled by a similar proportion. Fifty banks in the state went out of existence. Their wages paid with suddenly discredited banknotes, aggrieved workingmen in Milwaukee went on a rampage through the city’s financial district in late June 1861, ransacking the offices of Alexander Mitchell, the dean of Wisconsin banking. Yet throughout all this, bankers and public authorities worked towards a solution that substituted a better bond backing than the discredited southern securities, and by October 1861 the banks managed to return to a specie basis.

Ironically, the Koshkonong Bank might have survived had it remained solvent just a few days longer so as to benefit from the legislature’s suspension of specie payments. Van Norstrand’s attempt to evade his bond requirements through a sham ownership transfer was later blocked in 1866 by the state’s Supreme Court. Thus, in addition to losing his investment in the bank, he ultimately remained on the hook for his share of the bank’s useless currency. In the meantime, though, the good doctor mustered into the Union army, where he served as a surgeon attached to Wisconsin regiments. This being a land of second chances, Dr. Abraham H. Van Norstrand returned from the war to assume a prominent (if controversial) position as head of the Wisconsin State Hospital for the Insane.

The First National Bank of Fort Atkinson and Beyond

In unloading the Koshkonong Bank when they did, Joseph Clapp and Lucien Caswell dodged a bullet. Their next move was to be among the earliest investors in Wisconsin to organize a national bank under the new federal legislation. Leading a group of twenty Fort Atkinson residents that included members of their wives’ family, Clapp and Caswell incorporated the First National Bank of Fort Atkinson (Charter 157) on October 27, 1863 and opened for business in January 1864. For a brief period of time Caswell functioned as both President and Cashier of the new bank, even as he served in Janesville as Commissioner of the Board of Enrollment that was responsible for organizing the state’s military manpower contributions. For his part, Clapp had been elected to the state Senate for a two-year term (where his brother Mark also served) and was thus away in Madison. As a result, the new bank at first did business only from 9am to 11am each day. Later in 1864, however, Clapp was installed as President of the institution, with Caswell relegated to Cashier, an arrangement that served both well and prevailed for the next quarter century.

Even as a young man, Caswell asserted a leadership role in the community. In 1859, Caswell cemented that status by successfully negotiating with New York interests to resuscitate a bankrupt rail venture that would link Fort Atkinson with the outside world. In addition to his banking interests Caswell was intimately connected with the economic growth of Jefferson County. After a fire destroyed a furniture company in nearly Hebron, Caswell convinced its owner to relocate to Fort Atkinson. Caswell and another local doctor, Horace B. Willard, led an investor group that recapitalized the company, which reopened in 1866 as a producer of furniture and farm implements. In 1879, after a merger with a buggy maker the concern was renamed the Northwestern Manufacturing Company. Both Caswell and Clapp served on the Board of Directors, while Caswell was also an officer of the company. Caswell was quick to develop what would now be called side hustles. The year after co-founding that company, Caswell found time to start the Fort Atkinson Tannery with another brother-in-law, operate a mill, and create a family partnership by the name of May, Clapp, and Caswell to buy and sell farm products.

Joseph Clapp’s brief tenure in the Wisconsin Senate (1863-64) seems to have been his last stint of public service. Previously, he had played a number of local roles, such as Treasurer of the Town of Aztalan (1848) and representative for Milford on the Jefferson County Board of Supervisors (1852). Additionally, both Clapp and Caswell stood as candidates for city posts in Fort Atkinson in 1860. After taking the helm of the First National in 1864, Clapp occupied himself with tending to his various business interests, and was otherwise content with local, honorific roles like being Treasurer of the Fort Atkinson Anti-Horse Thief Society.

As the younger of the two, Lucien Caswell had the time and the energy to pursue a more ambitious political career that ultimately took him beyond the Badger State. Also, unlike his brother-in-law, Caswell produced a rather substantial family of four sons and two daughters, all of whom ended up residing in the Fort Atkinson area. As the children grew to adulthood, the four sons (Lucien Jr., Charles, Chester, and Harlow) all became involved in one way or another with their father’s and uncle’s enterprises.

Caswell was first elected to serve in the State Assembly in 1863, then in 1872 and 1874. A delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1868, Caswell entered political life more fully as a member of that party and steadfast supporter of General Ulysses S. Grant. After his terms in state politics, Caswell successfully ran to represent Wisconsin’s Second District in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1875 to 1883 (45th – 47th Congresses), and then again from 1885 to 1891 (49th – 51st Congresses). Throughout these years Caswell retained the title of Cashier at the First National Bank, but clearly he could not have been engaged in its day-to-day operations. For instance, the banknote illustrated below, issued sometime after 1874, bears the signature not of Caswell, but of Henry Ogden penned in his capacity as Assistant Cashier. As a young man, Ogden worked at the bank for a time (his occupation is given in the Census of 1870 as a “bank teller”) before attending medical school and becoming a doctor.

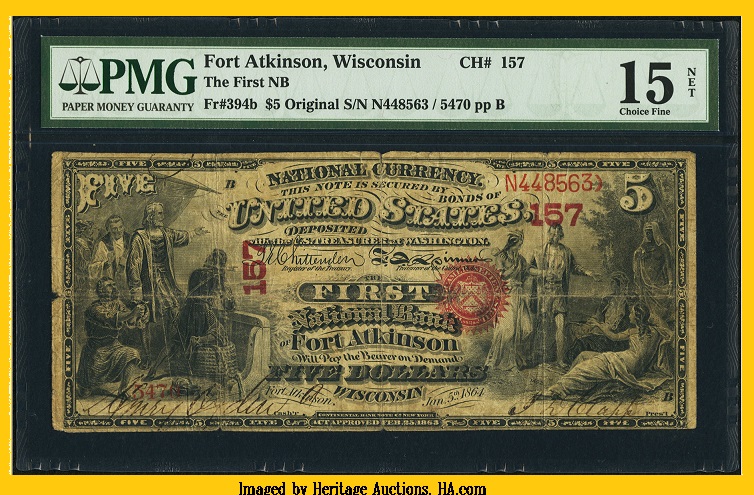

A $5 note on the FNB of Fort Atkinson, signed by Henry Ogden, Assistant Cashier, and Joseph D. Clapp, President. (Image source: Heritage Auctions)

As his sons grew older, Caswell brought them into his business interests. In the interlude between his two stints in the U.S. Congress, Caswell found time in July 1884 to organize yet another financial institution in Fort Atkinson, the Citizen’s State Bank. As with his other ventures, this was a family affair. Most of the bank’s stock was held by the Caswell family, though Joseph Clapp was a minor shareholder and served as a Director. While the elder Caswell also confined his role to a directorship, his oldest son Chester, who had trained up as a lawyer and was in partnership with his father since 1877, now assumed the post of Cashier. In 1878 Chester had married Julia Willard, daughter of Horace Willard, his father’s co-investor in the manufacturing business. In the new bank, Chester thus found himself working alongside his father-in-law, who was named Vice President.

Just about from its very beginnings, the First National Bank of Fort Atkinson had been run by Clapp as President and Caswell as Cashier, although as noted above it is doubtful that Caswell’s burgeoning political career allowed him much time to actually fulfill that position. Around 1880, Caswell’s second son, Lucien Jr., who was three years younger than Chester, joined the First National Bank as Assistant Cashier (the son also had a post at Northwestern Manufacturing). Unlike Henry Ogden, Lucien Jr. entered into a lifelong association with the First National. By 1891, he took the father’s place as Cashier (Lucien Sr. moving to Vice President) and the son would stay in that position for a full forty-five years more until his death in 1936. Likewise, Chester remained associated the Citizen’s State Bank for his entire career, becoming President before passing in 1931. The third son, George, started at Northwestern Manufacturing as a bookkeeper and later served as treasurer of the company until it closed down in the 1920s. Only the youngest son Harlow, a late child, pursued a career largely beyond the orbit of his father’s business interests. Born in 1874, Harlow was eighteen years younger than Chester. He studied medicine and later set up his practice in Fort Atkinson. Still, he is listed as serving as Vice President of the First National sometime in the 1910s.

As Representative of Wisconsin’s Second District for fourteen years, Caswell the politician was lauded in contemporary biographical sketches not for his rhetorical flamboyance but for his steady and measured pursuit of national and local interests. As he later opined in his memoirs about public service, “true greatness consists in unselfishness. A man of medium ability, who loses sign of his own personality in the work he is performing, but gives untiring devotion to the object of his employment, deserves the highest credit that can be given to man.” While he was referring to President Grant in this passage, Caswell might well have considered this an ideal which, as a loyal foot soldier for Republican administrations, he sought to live up to himself.

Caswell’s congressional career was a productive one. Included among the measures he was given credit for (or at least had a hand in) while in office were: the expansion of free mail delivery to smaller cities, as well as a decrease in the price of stamps from 3 to 2 cents; creation of a new appeals court; and starting the construction of the Library of Congress. In addition, Representative Caswell was involved in the tortuous reorganization of the Northern Pacific Railway, and enjoyed the particular honor of accompanying President Grant to the driving of the golden spike for that transcontinental line in 1883.

After failing to get re-nominated in 1890, Caswell retired from politics and returned to private life, soon embarking upon some extended travel to Europe. With their interests in Fort Atkinson’s only two financial institutions on top of their other business investments, Joseph D. Clapp and Lucien B. Caswell represented important figures in the economic growth and development of Fort Atkinson, and Jefferson County. They lived long lives. Each outlasted their spouses by many years (in Caswell’s case, two spouses). After Clapp passed away in 1900, Caswell assumed the Presidency of the First National Bank, with Lucien Jr. continuing as Cashier. The elder Caswell remained at that position until his own death in 1919.

As his generation dwindled in number, Caswell tended to his legacy in the form of his memoirs, which he composed with the assistance of his two daughters, Elizabeth and Isabel who, because of divorce and spousal death, had moved back home as their father’s caretakers. While entertaining enough in its accounts of a young boy growing up in territorial Wisconsin, the resulting manuscript is not terribly illuminating about the various events of the day in which Caswell participated as an elected official, or even about his various business ventures.

In those later years when Caswell was putting his memories to paper, Europeans were flooding America’s shores in search of a better life. Those Americans trickling in the other direction sought, variously, education, cultural sophistication, or sheer respite from the stifling commercialism and materialism of the New World. In the manuscript’s sections devoted to his own European travels, Caswell expressed appropriate awe for the splendors of the Old World. Yet he also evinced a Yankee’s prickly sensitivity to any signs of aristocratic snobbery in the places he visited. A tour of St. Peter’s Basilica provoked his disgust at the costs its opulence must have imposed upon the finances of the piously gullible common folk. Farms in Europe were too small; peasant women were worked too hard; and people everywhere were too resigned to their squalid lot. Arriving back in New York City after his first trip, Caswell enjoyed nothing more than indulging in some hearty American cuisine and venturing uptown to visit the tomb of his beloved General Grant. One senses, in Lucien B. Caswell’s case, that he arrived back home from his travels more of an American than when he left.

..........

REFERENCES

Ancestry.com, for minor biographical details including census records.

Aikens, Andrew J. and Lewis A. Proctor, Men of Progress. Wisconsin (Milwaukee: The Evening Wisconsin Co. 1897).

Biographical Sketches of Old Settlers and Prominent People in Wisconsin Vol I (Waterloo, WI: Huffman & Hyer, Publishers 1899).

Caswell, Lucien B. “Autobiography of Lucien B. Caswell” mimeographed typescript dated March 7. 1914, bound with cover letter from American Heritage Publishing Co. dated August 30, 1971. Caswell quote p. 208 (manuscript in author’s possession).

Conant, Charles A., A History of Modern Banks of Issue 5th ed. (G. P. Putnam’s Sons 1915).

Daily Freeman [Waukesha, Wis.], July 17, 1883

Daily Gazette [Janesville, Wis.], March 26, 1861.

Daily State Journal [Madison, Wis.], November 17, 1858.

Democratic State Register [Watertown, Wis.], December 6, 1852.

Dougherty, Thomas, The Best Specimen of a Tyrant: The Ambitious Dr. Abraham Van Norstrand and the Wisconsin Insane Hospital (University of Iowa Press 2013), chs. 1-2. Caswell quote p. 44.

Fort Atkinson [Wis.] Standard, March 29, 1860.

History of Jefferson County, Wisconsin (Chicago: Western Historical Company 1879).

Krueger, Leonard Bayliss, History of Commercial Banking in Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Studies in the Social Sciences and History, Number 18 (Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin 1933), chs. IV-V.

Ott, John Henry, Jefferson County Wisconsin and its People Vol. I (Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co. 1917).

Usher, Ellis Baker, Wisconsin. Its Story and Biography, 1848-1913 Vol IV (Chicago and New York: The Lewis Publishing Co. 1914).

Watertown [Wis.] News, March 22, 1861; March 29; 1861; February 17, 1875; April 19, 1882; March 27, 1889; May 6, 1891.

Watertown [Wis.] Republican, April 19, 1882.

Watertown [Wis.] Chronicle, April 12, 1848; May 5, 1852.

Weekly Jeffersonian [Jefferson, Wis.], September 22, 1859.

Wisconsin, Annual Report of the Bank Comptroller of the State of Wisconsin for the Year 1858 (Madison, Wis.: Atwood & Rublee, Printers 1858).

Wisconsin, Journal of the House of Representatives of the Fourth Legislative Assembly of Wisconsin Territory (Madison, W.T.: Simeon Mills, Territorial Printer 1845), p. 196.

Wisconsin. Journal of the Senate of Wisconsin, Annual Session 1861 (Madison, Wis.: E. A. Calkins & Co. 1861), pp. 570-1

Wisconsin. Private and Local Laws Passed by the Legislature of Wisconsin in the Year Eighteen Hundred and Sixty-one (Madison, Wis.: Smith & Cullaton, State Printers 1861), ch. 4.

Wisconsin State Journal [Madison, Wis.], April 25, 1861.

Wisconsin State Register [Portage, Wis.], March 30, 1861.

Wolka, Wendell, “Wisconsin Free Banking: A Brush with Disaster” Parts 1-3 Paper Money XIX (January-February 1980), pp. 11-12; (March-April 1980), pp. 80-86; (May-June 1980), pp. 156-160.

.....