Politics and Paper Money

LBJ, Inflation, and "Great Society Funny Money"

CONGRESSIONAL MIDTERM ELECTIONS in the United States usually deliver some sort of rebuke to the party in power. The situation facing the current Biden Administration in 2022 is no different. Indeed, the Democrats face a stiff electoral headwind in the form of surging consumer prices, with the annual rate of inflation reaching levels not seen since the 1970s. Emerging from a swirl of pandemic related supply-chain disruptions, government stimulus spending, easy Fed money, labor shortages, and now Ukraine-related shocks to world commodity prices, a strong whiff of inflation is certain to concentrate the minds of the voting public this November.

Much like 2022, the Democrats braced for a similar storm in the late 1960s. Then, the Administration of Lyndon Baines Johnson faced the possibility that the conflicting demands of Vietnam-related military spending and Great Society welfare programs might ignite an uncontrollable wage-price spiral. Recognizing an electoral opportunity, during the months before the 1966 midterm elections Republicans stressed the damage that higher prices would inflict upon consumer pocketbooks.

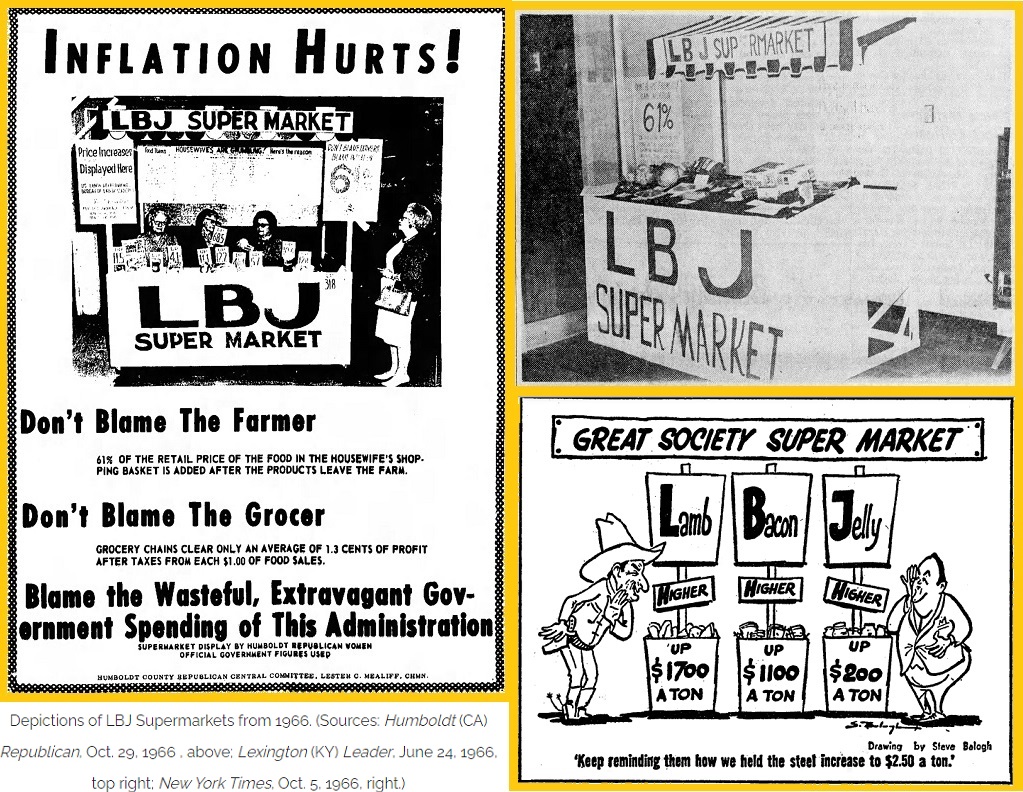

In an astute twist, Republican politicians argued that, for all of President Johnson’s attempts to address poverty through greater social welfare spending, inflation itself impoverished consumers by reducing the purchasing power of their paychecks. To dramatize this possibility, Republicans set up across the country thousands of displays they called “LBJ Supermarkets” that illustrated the price hikes which had beset a range of consumer goods.

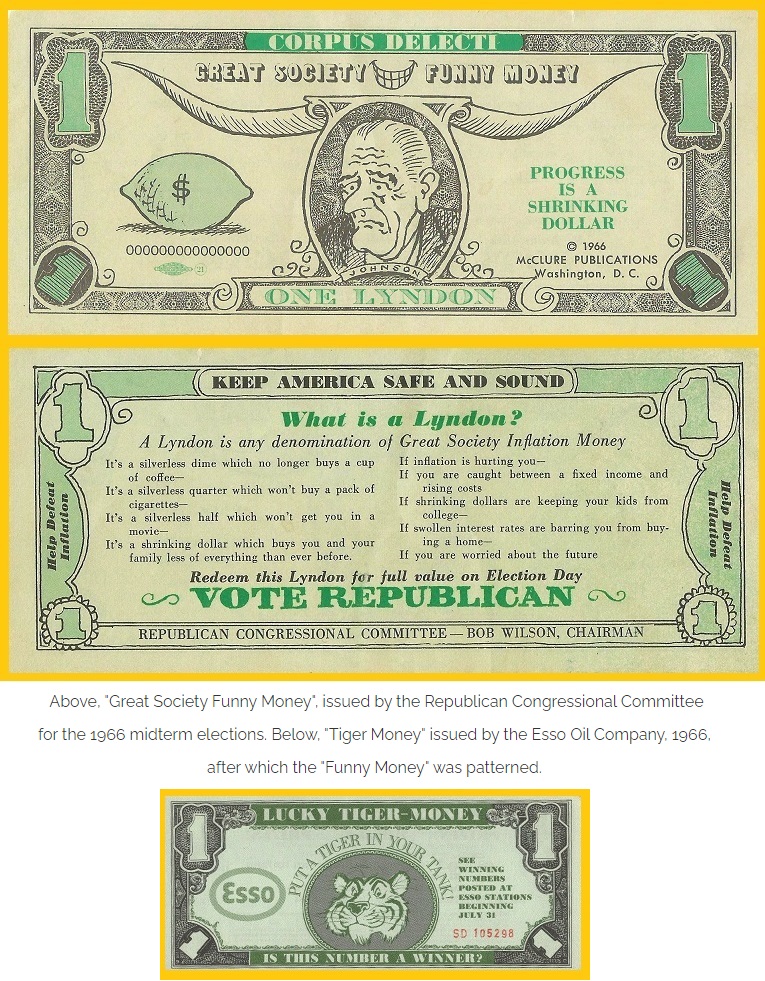

In addition to these displays, Republicans disseminated by the many thousands pieces of political scrip they called “Great Society Funny Money,” denominated in “Lyndons,” to underscore the connection between the high levels of government spending required by the Democrats’ social welfare agenda and rising prices. While the two issues were not necessarily related, the scrip also linked Great Society spending to the post-1964 disappearance of silver from the nation’s small change and its replacement by clad-copper coinage.

As this minor bit of satire entered political circulation in late 1966, a characteristically uptight Secret Service did its part to draw attention to the scrip by temporarily suspending its production, on the grounds that someone might mistake a “Lyndon” for a real (albeit depreciated) American dollar.

Guns vs. Butter in the Great Society: LBJ Supermarkets

The “Great Society” refers generally to the gamut of government programs—ranging across a variety of policy areas such as education, transportation, the environment, but especially social welfare—that were put into place by Lyndon Johnson and a Democratic Congress between 1964 and 1968. Taken together, these programs represented the largest intervention by the national government in American society since the New Deal of the 1930s. Core legislative components of the Great Society were written into law by the 89th Congress (1965-1967). At the same time that Johnson pushed this domestic agenda, he also made the fateful decision in July 1965 to escalate the military conflict in Vietnam. These parallel initiatives, combined with the stimulative effect of the 1964 tax cuts, ignited a wage price-spiral that took nearly twenty years to get under control.

Ever since the Korean War, inflation had been a minimal factor in the American economy, running at an annual average of just 1 ½ % between 1952 and 1965. But, as price increases ticked up in 1965, Republicans were quick to notice this and exploit these increases for political gain. Unlike civil rights or the Vietnam conflict, inflation was a valence issue around which the voting public could easily unify: What consumer would be in favor of rising prices? Cleverly, Republicans framed the inflation problem in the language of the Great Society itself. Since inflation impoverished consumers, fighting against it was just as reasonable for fighting for Great Society anti-poverty programs.

President Johnson was not unaware of the inflation threat; his own experts in the Council of Economic Advisers were telling him in December 1965 that a tax increase would be necessary to tamp down on excessive demand. Much to Johnson’s annoyance, the Federal Reserve itself had raised interest rates that same month, and for the same reason. Johnson resisted doing anything because he sensed that, were he to acknowledge inflation as a constraint, it would force him to be explicit about a tradeoff between fighting in Vietnam and building the Great Society—between guns and butter—that he sought to avoid.

The Republican campaign against inflation began as early as August 1965, when two female Representatives, Florence P. Dwyer (R-NJ) and Charlotte T. Reid (R-IL) created a television spot for the Republican National Committee depicting an “LBJ Supermarket” whose higher prices were contrasted with those prevailing a year before. Pushed by the Committee’s chairman, Ray C. Bliss, by late 1966 some 3,500 versions of these ‘pop-up’ LBJ Supermarkets appeared in various locales around the country. In September Michigan Senator Robert P. Griffin launched what he called “Operation Price Tag”, an effort to mobilize housewives to distribute questionnaires encouraging shoppers’ awareness of higher prices at supermarkets throughout the state.

Great Society Funny Money

Along with these efforts came the distribution of several hundred thousand pieces of satirical scrip dubbed “Great Society Funny Money”. A product of the Republican Congressional Campaign Committee, the plan was to make available supplies of the scrip to Republican candidates across the country at a cost of $15 dollars per thousand, and $20 per 10 thousand. A Republican-affiliated media company, McClure Publications, was reported to have ordered one million pieces of the scrip to be printed by the Doyle Printing and Offset Co., of Washington, D.C.

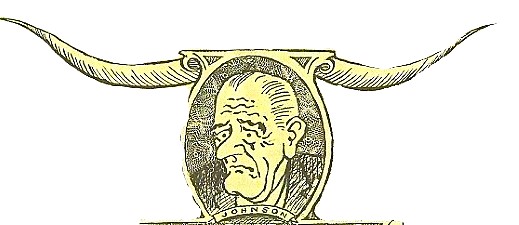

The Republicans’ “Funny Money” is simple in appearance. A spokeswoman for McClure, Barbara Peet, explained that the note’s design was inspired by a premium coupon being circulated at the time by the Esso Oil Company called “Tiger Money.” Printed and shaded in green, the front sports a rather morose depiction of President Johnson, his portrait framed by a pair of Texas longhorns, to its left a large lemon. At the top appears a (slightly misspelled) Latin phrase, “Corpus Delecti [sic]”, suggesting that the bill’s very existence was evidence of a crime. The back of the bill addresses “What is a Lyndon?” in the form of a catechism that makes references to the disappearance of silver from small change as evidence for the inflationary harm inflicted by the Great Society: “It’s a silverless dime which no longer buys a cup of coffee / It’s a silverless quarter which won’t buy a pack of cigarettes / It’s a silverless half which won’t get you in a movie—” Voting that November for Republicans would, the note exhorts, “redeem this Lyndon for full value on Election Day.”

Around this time, as guardians of the U. S. dollar the Secret Service had a veto over depictions of currency, satirical or otherwise, that in retrospect seems excessively severe. Given who it depicted, “Great Society Funny Money” seemed hardly likely to fool anybody. At first the Secret Service signed off on the production of “Lyndons”, insisting only that the notes be a little bit larger than real money so as not to trick the automatic change-making machines of the time. Then, for some reason, the Secret Service changed its own mind and referred the note to the U.S. Attorney’s office for a second opinion. An official there, Alfred Hantmann, pronounced the notes “scurrilous.” This temporarily stopped the presses. McClure’s Barbara Peet accused the Administration of trying to quash “Lyndons” for political reasons. Newspapers around the country picked up the story, giving the Republicans’ stunt valuable publicity. Production quickly recommenced and the Republican Campaign Committee was soon shipping the notes out to interested candidates.

The Republican-leaning Chicago Tribune speculated archly about what would happen if “Lyndons” proved to be superior to a devalued U.S. dollar: “Gresham’s Law will then drive the Lyndon out of circulation … If the time comes when $1 will buy only one Lyndon, we suppose the grocer will start demanding payment in Lyndons instead of dollars … France will begin using gold to buy Lyndons, and the treasury department will face a difficult choice: to start printing counterfeit Lyndons, or to devalue the dollar.”

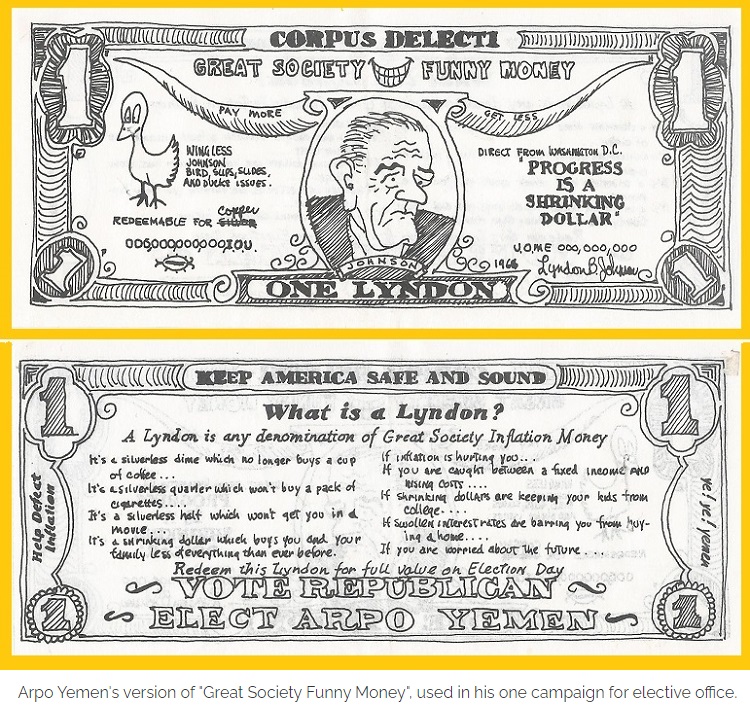

Another version of “Great Society Funny Money” showed up in one very specific Congressional contest during the 1966 election cycle. Michigan’s 15th district saw a Republican challenger, Arpo Yemen, running against the Democratic incumbent William D. Ford. As a campaign handout, Yemen made use of a piece of scrip that was clearly derivative of the national Republican product but different in obvious ways. It is printed, black-and-white, in a whimsical-looking free hand style. The same, gloomy visage of Johnson looks to the right, rather than to the left. Instead of a large lemon, to the left of the portrait is a “wingless Johnson bird [that] slips, slides, and ducks issues.” On the reverse, the text is essentially the same as the first version, save for the addition of “Elect Arpo Yemen” at the bottom.

Arpo Yemen, whose full last name was Yemenijian (or Yemenidjian), was a minor figure in Michigan’s Republican politics. An Armenian refugee whose family escaped both the Turks and the Nazis via Vienna before ending up in postwar United States, Yemen landed in Detroit in 1950. There, he earned degrees in civil engineering and the law at Wayne State University, after which he set up a practice focusing on immigration and worker’s compensation. A supporter of Governor George Romney in 1962, Yemen organized an “Armenians for Romney Club”, a curiosity that gained him the Governor’s attention, who rewarded Yemen with appointments to the state’s Labor Mediation Commission and the Workmen’s Compensation Appeal Board. Yemen later served as a District Court Judge for Dearborn Heights. In 1966 Romney recruited Yemen for his one venture into electoral politics during the congressional midterms, in which he was trounced by the Democrat, William D. Ford (no relation to famous Fords) even though Republicans as a whole did very well in that state.

LBJ and the Politics of Inflation

The Republicans’ anti-inflation campaign, including the proliferation of “LBJ Supermarkets” and the printing of “Great Society Funny Money,” contributed to Republican successes in the 1966 midterm elections, where they gained 47 House seats and picked up three in the Senate. Wary that his own standing might be tarnished by an electoral debacle, LBJ kept his distance from the contest and did not actively campaign for Democratic candidates. While these Republican gains were not enough to wrest control of Congress, the results did put a big dent in the Democrats’ commanding majorities. They also ensured that Johnson would be unable to get major legislation through the 90th Congress, effectively stalling any extension of his vision for the Great Society.

The conventional view of Lyndon Johnson’s dilemma describes it as a tradeoff between guns and butter. Unwilling to make the hard choice between funding the Great Society and paying for the escalating Vietnam War, Johnson introduced the twin viruses of deficit spending and inflation into the nation’s political economy. Key here was his refusal to consider his economic advisers’ recommendations throughout 1966 to accept the need for a tax increase that would dampen surging domestic demand. Johnson also disliked the prospect of imposing wage and price controls, since those invariably smacked of wartime expedients. Thus, as the historian Doris Kearns put it, “in the absence of either wage and price controls or a tax increase, the Great Society became the sacrificial lamb of a rising inflation.”

While there is much truth in this, it doesn’t entirely characterize the contingent and dynamic qualities of the situation Johnson and the Democrats faced. Johnson regarded his party’s crushing defeat of Goldwater and the Republicans in 1964 as a mandate for creating the Great Society, but he knew that he had to get his agenda through a closing legislative window. Johnson had an incentive to push early for vast programmatic commitments and then to defend their funding later. In doing this, Johnson was also driven by a long-running and very personal rivalry with the Kennedy family and Bobby Kennedy in particular, who regarded Johnson as an illegitimate usurper of his slain brother’s legacy. Pursuing the Great Society enabled Johnson both to claim stewardship of this legacy and yet go beyond it by defining his own contributions to American life.

Johnson's campaign against Goldwater required him to stress his anti-communist bona fides by being muscular with respect to Vietnam. Towards this end, creating a pretext for and engineering the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in August 1964 served a domestic electoral purpose that year at the price of boxing in his domestic agenda later. As the magnitude of America’s Vietnam involvement became apparent, pursuing it entailed sacrifices that Johnson had an incentive to downplay and postpone. In the words of his assistant, Joseph Califano, Johnson “was riding two horses at the same time.” An honest discussion of the fiscal burdens of the Vietnam War, the President feared, would only provide opponents of his Great Society achievements with the pretext for reversing them. Johnson thus dissembled about the mounting military bill, hoping that the conflict could be brought to some kind of closure by 1967.

As a result, by the time Johnson came around to publicly accepting the need for, and inevitability, of a tax increase, neither Republicans nor Democrats were willing to go along with him. Because he had hid the impending cost of the war, the public was not primed to accept tax increases in any spirit of shared sacrifice. Indeed, for their own reasons both conservatives and liberals could unite to oppose Johnson’s proposals for a tax surcharge, but for different reasons. Conservative were against any tax increases because they preferred to push funding cuts for Great Society programs. Liberals were against tax hikes because they sought to force Johnson to disengage from Vietnam.

Ultimately, Johnson was able to sign a temporary tax surcharge bill in August of 1968, at which point the nation faced a gaping budget and trade deficits, as well as dwindling gold reserves. The rising price of silver had not only driven coinage from circulation but forced the retirement of silver certificates. When Congress finally passed legislation in June 1967 allowing the Treasury to end the certificates’ redemption in silver, this only confirmed for Republicans that Johnson was pursuing “funny money” policies. Later that year, when the International Monetary Fund agreed to create a new form of liquidity called Special Drawing Rights, the hard-money editorialists at the Chicago Tribune groused that “in light of the legerdemain, the IMF might appropriately transpose its initials to IFM, standing for international funny money.”

By 1971, the U.S. dollar was no longer redeemable in gold, either. “Funny Money” was no longer a partisan epithet, but a description of basic monetary reality. For the politics of inflation in the United States, ignited during the Johnson Administration, this was only the beginning.

..........

REFERENCES

Califano, Joseph A., Jr. The Triumph & Tragedy of Lyndon Johnson: The White House Years (New York: Simon and Shuster 1991), p. 120.

Chicago Tribune, October 9, 1966; October 4, 1967.

Courier-News (Bridgewater, NJ), August 6, 1965.

Dallek, Robert, Flawed Giant: Lyndon Johnson and His Times, 1961-1973 (Oxford University Press 1998), pp. 303-311, 335-339, 392-399.

Detroit Free Press, October 28, 1966 [profile of Arpo Yemen].

Kearns, Doris, Lyndon Johnson and the American Dream (New York: Harper & Row 1976).

Michelmore, Molly C. Tax and Spend: The Welfare State, Tax Politics, and the Limits of American Liberalism. University of Pennsylvania Press 2012., ch. 3

Washington Post, September 25, 1966 [on "Funny Money". Many versions of this story appeared at this time around the country].