Cartography and Currency – II

Mapping the Group of Twenty

WHILE IT DID WELL at the box office internationally, Greta Gerwig’s film Barbie (2023) created a cartographic kerfuffle with its incidental depiction of Barbie’s fantasy map of the world (pictured above) that includes an unmistakable version of China’s “Nine-Dash Line.” Not recognized by any other sovereign nation or international tribunal, the Nine-Dash Line asserts China’s conceit to control all the waters and the bits of territory in the South China Sea at the expense of its neighbors’ claims. Countries in southeast Asia took umbrage at Hollywood’s latest attempt to pander to Chinese nationalist sensibilities, with Vietnam going so far as to actually ban Barbie from its theaters.

The field of cartography is notorious for such dust-ups. Making maps is an intrinsically political enterprise. Over the years, Israel and its opponents regularly traded insults by producing maps that alternately erased the Jewish state or a putative Palestine. Turkey objected to maps depicting a hypothetical Kurdistan, even as President Erdogan’s neo-Ottoman ambitions have generated their own cartographic fantasies. Dua Lipa, the British pop star of Albanian extraction (and who incidentally plays a Barbie in the new movie), created a stir in 2020 by tweeting a map of a “Greater Albania” that had gobbled up Kosovo. About a decade ago, China printed a map in its passports that not only depicted the Nine-Dash Line but asserted its sovereignty over Taiwan as well as those parts of Jammu and Kashmir whose control it has disputed with India. China’s travel document provoked the ire of countries across Asia, with immigration officials in (again) Vietnam simply refusing to place visa stamps on the relevant passport pages.

Sometimes, the cartographic offense is unintentional but unavoidable, as occurred in 2020 when Saudi Arabia issued a commemorative banknote commemorating its hosting of the international Group of Twenty meeting.

2020: Saudi Arabia and its Commemorative 20-Riyal Note

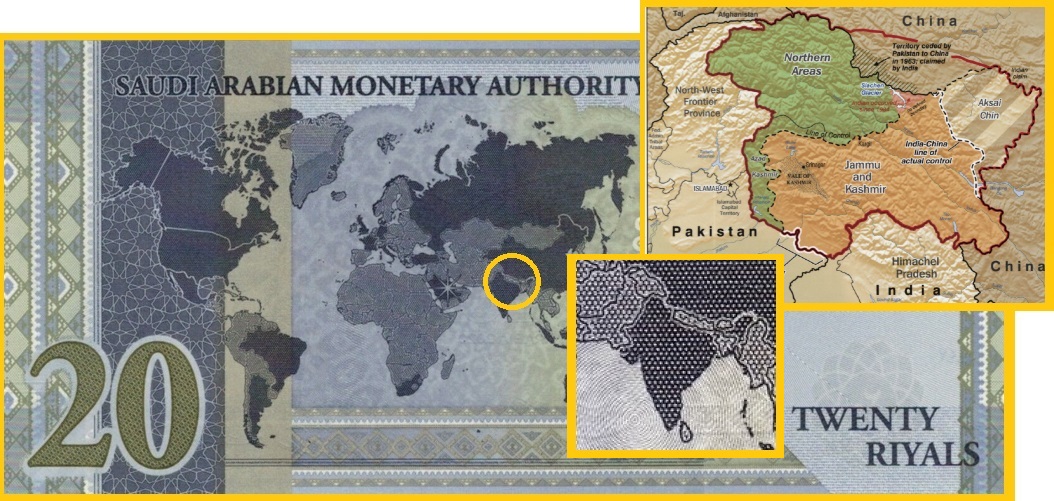

Front and bank of Saudi Arabia's 20 riyal note, issued to commemorate its hosting of the Group of Twenty summitt in 2020 (Image source: Numista).

First convened in 1999, the Group of Twenty (G20) is an organization of the world’s twenty largest economies whose leaders meet yearly to discuss issues relating to global economic and financial governance. The Presidency of the G20 rotates on a yearly schedule among its members, and while that status is mostly ceremonial, it is nonetheless a prestigious event for the host nation to sponsor. Saudi Arabia’s turn to do so for the fifteenth G20 Summit in November 2020 came at a time when the country’s reputation was still suffering from the murder of the journalist Jamal Khashoggi; hosting the G20 offered its de facto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammad Bin Salman, a safe and high-profile opportunity to burnish the country’s image, even if the Covid epidemic confined the summit to an online experience. To mark the occasion, in October the Saudis issued a commemorative 20-riyal banknote featuring MBS’s father, King Salman, on the front and a map of the world on the back, with the G20 countries identified with a darker color shade.

While the issuance of a numismatic memento was an unremarkable gesture, unfortunately for the Saudis the banknote’s representation of the world was hardly uncontroversial. Both India and Pakistan took issue with the way it depicted the geographical regions known as Jammu, Kashmir, and Ladakh as separate entities, rather than as bits of India or Pakistan. India was particularly incensed, as the Hindu nationalist government of Narendra Modi had only the year before managed to strip Muslim-populated Jammu and Kashmir of their special status under the Indian constitution. Likewise, the sparsely-settled Ladakh, home of the notorious Siachen Glacier over which Indian and Pakistani troops freeze to death, was also annexed as Indian union territory. Less vociferous in its reaction, Pakistan complained that the Saudi banknote’s depiction of an independent Kashmir included the part of Kashmir it controlled, as well as the Gilgit-Baltistan area. China, with its own territorial claims in Aksai Chin (disputed with India) but a big customer of Saudi oil, prudently kept its mouth shut.

Back of the Saudi note, with an enlarged inset of its depiction of India's border regions. Second inset depicts regional border claims (Image source: CIA).

While it required a decent magnifying glass for anybody to fully appreciate the offensiveness of the banknote’s map, India threatened for that reason to boycott an important international meeting. Only after Saudi Arabia promised to retire the controversial banknote did Indian Prime Minster Modi agree to participate. When India’s turn came to host the G20 summit in 2023, the tables were turned. Although it didn’t issue its own commemorative banknote, India insisted upon holding preliminary working group sessions concerning tourism in, of all places, Kashmir. Asserting that it would not participate in meetings in “disputed territory”, China refrained from attending those sessions, as did the Saudis, who were mindful of the optics of countenancing militarized Hindu rule over a Muslim Kashmiri population. Officials from other Muslim-majority countries like Turkey and Egypt also stayed away.

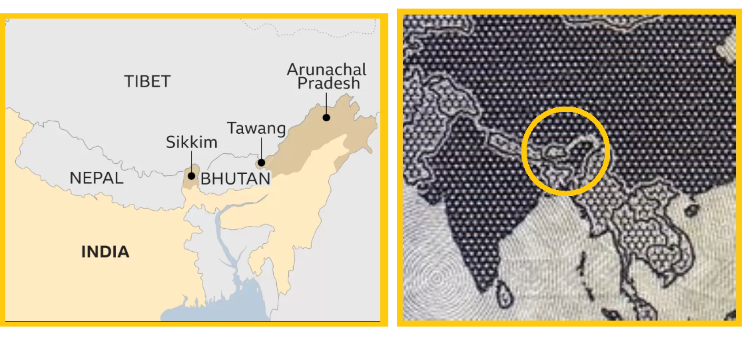

A short while later, just as G20 leaders were about to convene their eighteenth summit in New Delhi in early September 2023, it was China’s turn to poke its own cartographic stick, this time issuing a revised version of its national map that reprised its existing territorial claims in the South China Sea and those with respect to India and Pakistan. The new map was duly condemned by all the affected governments. India in particular took issue with the representation of its easternmost state, Arunachal Pradesh, which China’s map annexed as its own territory under the designation “South Tibet.” Once known as the North-East Frontier Agency Region, the area had been briefly occupied by the Chinese during the Sino-Indian War of 1962. By 1987, India had renamed the area Arunachal Pradesh and upraded its status from a union territory to a state. Unlike Jammu and Kashmir, the status of Arunachal Pradesh was not an issue for the Saudi Arabian 20 riyal note, as its representation of India’s eastern extent was ambiguous enough to warrant objections from neither India nor China.

India's easternmost State of Arunachal Pradesh, alongside an elargement of how it appears on the Saudi banknote (Image Source: BBC).

If India appeared as the injured party across these two episodes, the shoe has also been on the other foot. In November 2019, India issued an updated official map of its own that angered Nepal by including the disputed Kalapani border area as part of India. While Kalapani is geographically far too small to be detectable on the Saudi banknote, the dispute over it nonetheless worsened relations between India and Nepal (which has been drifting into China’s orbit), giving rise to a “cartographic war” the following year as Nepal countered with a map asserting its own territorial interests.

It would be tempting to minimize the significance of these dueling maps as merely mirroring the underlying disputes and power rivalries. And they are indeed that. However, the nationalist passions inflamed by these ostensibly symbolic gestures have consequences. In the wake of the Indian uproar over China’s cartographic provocation, Chinese President Xi Jinping snubbed the 2023 G20 summit, sending Premier Li Qiang to India in his place. While this may also have been reflective of China’s more general disillusionment with the G20 as a vehicle for its interests, it still put a dent into a major forum for international cooperation.

A map not only describes a status quo, it also affirms the status quo. When there is no agreement about that status quo even is, maps become radically indeterminate artifacts in that there can be no one map describes a view of reality that everybody shares. In that circumstance, all maps are necessarily distortions in one way or another. By implication, there was no possible map of the world that the Saudis could have put on their banknote that would have been suitable to all the aggrieved parties.

.....

REFERENCES

https://www.dawn.com/news/1587850

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/may/22/china-saudi-arabia-boycott-g20-meeting-india-kashmir

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-66669341

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-53062484

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-52967452

https://thediplomat.com/2019/11/indias-updated-political-map-sparks-controversy-in-nepal/