Mrs. Oliver Harriman’s Bet on the Lottery

Introduction

WHILE LOTTERIES SERVED important financial purposes in the early United States, by the second half of the 19th century their operation was increasingly restricted or suppressed by the American states. Public disapproval of lotteries peaked with federal action undertaken to shut down the Louisiana Lottery in 1890. This form of gambling would remain illegal in the United States for another seventy years.

By the 1930s, however, interest revived in lotteries as a revenue source in the United States and elsewhere. With the onset of the Great Depression, public attitudes towards gambling became more permissive, and legal restraints were relaxed on certain types of games of chance. Retail marketers also responded to the economic downturn by popularizing various kinds of “gift enterprises” that skirted legal prohibitions on gambling. Lotteries themselves were touted as revenue generators that might fund unemployment relief or finance the growing levels of public debt. The fact that several foreign governments (notably Ireland) ran lotteries whose tickets were widely sold in the United States provided an additional reason for creating home-grown alternatives.

During these years, a dozen different states considered laws to restore this form of gambling. Lottery advocates also pursued legislation at the federal level. One organization in particular, the National Conference on Legalizing Lotteries founded in 1934, sought to promote such political outcomes by sponsoring lottery-like contests that were tricked out as games of skill. Led by a strong-willed New York socialite, Mrs. Oliver Harriman, this advocacy group provoked clashes with the Post Office and other legal authorities in order to gain publicity for the cause of legalization. Challenging the prevailing moral disrepute in which lotteries languished, Harriman argued that, as a practical matter, lottery revenues would represent a resource for the poor, while benefiting the entire economy by keeping the purchasing power of lottery players from leaking out of the country into the coffers of foreign governments.

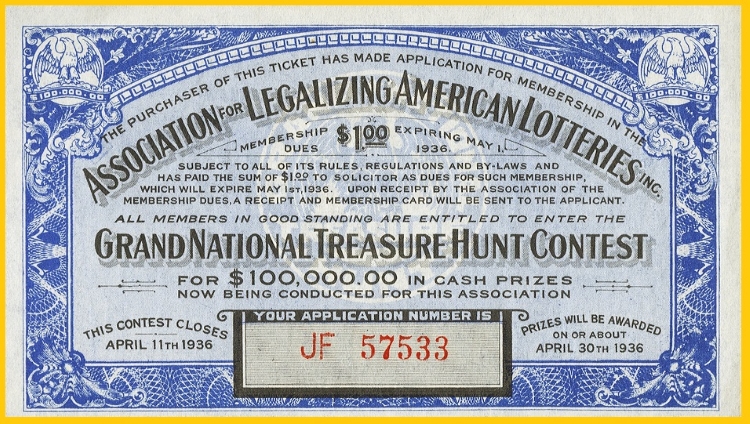

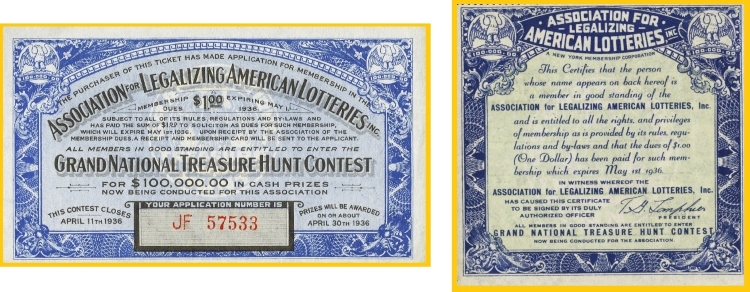

While initially successful in sponsoring contests that promoted the benefits of lotteries, the efforts of Harriman and her group were quickly spoiled by opportunists who, simply seeking profit rather than pro-lottery reform, imitated the strategy with their own, parallel contests. One figure in particular, the celebrity aviator Thomas G. Lanphier, Sr., had initially worked with Mrs. Harriman’s group before setting up his own, alternative lottery advocacy organization, the Association for Legalizing American Lotteries. Unlike Harriman’s group, these competitors went so far as to issue their own, thinly-disguised lottery tickets, an example of which is pictured below. All of this became too much for the Post Office, which at the time was the chief enforcer of federal anti-lottery laws by dint of its control over the mails. Even though it had given the green light to Mrs. Harriman’s original scheme, with the appearance of these more aggressive variants, the Post Office in early 1936 cracked down on all of them, including Mrs. Harriman’s. With this enforcement upheld by the courts in 1938, the movement to legalize lotteries quickly sputtered out.

An "application for membership" to the Association for Legalizing American Lotteries, 1936. This erstwhile lottery ticket sought to circumvent legal restrictions on lotteries. (Image Source: Heritage Auctions.)

The Lottery in American Life

As John Samuel Ezell documented in his classic study of the lottery in the United States, well into the early 19th century lotteries flourished not merely as a gambling pastime but as an alternative to taxation and as a means of capital formation. Even for private transactions involving big-ticket items (“merchandise raffles”), lotteries functioned to concentrate purchasing power in communities otherwise lacking in money and currency. Beginning with the scandal during the 1820s involving the Grand National Lottery in Washington D.C. , public attitudes turned against legal lotteries, and by the outbreak of the Civil War most states had banned them.

The campaign against lotteries in 19th century America peaked with the elimination of the notoriously corrupt Louisiana State Lottery. As other states banned lotteries, the persistence of this one became a notorious outlier, especially as other states resented the exodus of funds spent by their own citizens. Congress acted in 1890 to authorize the Post Office to ban the Louisiana Lottery’s material from the U.S. mails, and in 1895 to outlaw interstate trafficking of lottery materials as an exercise of its commerce powers.

As lotteries were legally restricted, law enforcement at all levels of government became increasingly concerned with the definition of a lottery, since many entrepreneurs offering gambling experiences sought to cloak their enterprises in order to avoid prosecution. An even broader array of commercial propositions that otherwise had nothing to do with gambling sought nonetheless to use lottery-like arrangements as marketing or advertising devices. Accordingly, law enforcement increasingly took aim at the proliferation of so-called “gift enterprises” which might be found illegal if their lottery character were too pronounced.

Under the well-developed jurisprudence of gambling, a contest was deemed a lottery if it contained three elements: chance, prize, and consideration. That is, individuals who (1) paid some entry fee or gave up something of value [the consideration] in order to (2) participate in a contest whose outcome did not depend upon any skill of the participants [chance] for the opportunity to (3) receive some benefit that was disproportionately large relative to the consideration [prize] were taking part in an illegal lottery, whether or not it was labeled as such.

After World War I, restrictions on gambling relaxed somewhat, both in the United States and elsewhere. While lotteries had never entirely disappeared in Europe, desperate fiscal circumstances in the wake of the War led to the reintroduction of public lotteries in Austria, Belgium, Germany, and Italy, especially in connection with the marketing of government debt (so-called “premium bonds”). In 1933, France established a national lottery to finance war pensions; Belgium adopted a lottery the year after. Although at this time Great Britain considered, but did not adopt, a lottery, the famous Irish Hospitals’ Sweepstakes, begun in 1930, quickly became a favorite of British punters, who comprised most of the lottery’s winners. The Irish lottery operated much to the annoyance of British lawmakers, who complained about the amount of money crossing the Irish Sea.

An Irish Hospitals' Sweepstake ticket from 1934. Winning tickets were determined by the results of several different horse races held in Great Britain each year. This particular ticket was based upon the Cambridgeshire Handicap run at Newmarket, England (Image Source: eBay).

After British authorities initiated a crackdown on ticket sales in 1934, promoters of the Sweepstakes focused their marketing on the United States, where its drawings and American winners received extensive popular media coverage, despite federal attempts to obstruct the flow of ticket sales and even restrict the dissemination of media reports about the lottery. The magnitude of the lottery-related money flows leaving the United States was not insignificant. One widely-cited figure from 1932, given by the Post Office, estimated the amount of money prevented from leaving the country through the interception of lottery tickets and other materials to be half a billion dollars.

In addition to the influence of these foreign examples, the onset of the Great Depression and the end of Prohibition contributed, in their ways, to the loosening of attitudes about a public lottery. In particular, the fiscal impact of the Great Depression stimulated interest in lotteries as revenue devices, as falling tax receipts encountered increased demands for expenditures on relief. As the Washington Post observed in early 1934, “outlawed liquor is back, and pari-mutuel betting—with its very sizable percentage to State governments—has been legalized in eight States in the last year. And now the lottery, with its magic multiplication of dollars, has seriously entered the ring as a means of balancing budgets and doing other odd jobs around city, State, and Federal Treasuries.”

Mrs. Oliver Harriman and the National Conference on Legalizing Lotteries

Agitation in the early 1930s for a relaxing of lottery laws was invariably associated with one single person: Mrs. Oliver Harriman, Jr. (1873-1950). Born Grace Carley in Louisville, Kentucky, she became a New York socialite by dint of her marriage to the stockbroker Oliver Harriman. Throughout her life Mrs. Harriman devoted herself to a number of charitable and philanthropic pursuits, including the Camp Fire Girls and victims of the Armenian genocide. In her telling, her interest in advocating for the lottery as a revenue source arose from a social encounter in 1934 with the Mayor of Dublin, who in some facetious way expressed to her his thanks to the American people for financing hospitals in his country through the purchase of Irish Hospitals’ Sweepstakes tickets.

A young Mrs. Oliver Harriman. Born Grace Carley, in Louisville, Kentucky, she married Oliver Harriman in 1891 and became a fixture of New York's social scene for decades. (Image Source: Library of Congress).

Of a pragmatic bent, Harriman approved of lotteries as a revenue source that would address the mounting social stress occasioned by the Depression, especially when declining receipts from conventional tax sources ran up against budget deficits. By providing a domestic alternative, a legal lottery would also stem the flow of funds which Americans directed towards the Irish Sweepstakes and other foreign lotteries. As with her attitude towards Prohibition, Harriman had little sympathy for the traditional moral arguments against gambling. Repeatedly pointing out that Americans had resorted in the past to lotteries in order to finance many worthy projects, Harriman contended that legalizing them again would only recognize people’s inherent propensity to play games of chance. As for the undeniable connections between gambling and organized crime, Harriman simply responded, “surely it is better to have hospitals and institutions receive money than a lot of racketeers.”

In July of 1934 Harriman and a number of other women in her social circle formed the National Conference on Legalizing Lotteries (NCLL) as their forum for promoting the decriminalization of lotteries. There were already signs that their cause enjoyed a favorable public headwind. Later that year New York City government, which was struggling to find additional funding for unemployment relief, itself looked into a municipal lottery even though this was explicitly prohibited by the state’s constitution. This official interest in games of chance did not prevent the authorities from attempting to uphold the law when it came to unauthorized forms of gambling. For example, in early 1935 the city experienced an outbreak of violence as criminal organizations struggled over control of the “numbers” game. Opponents of lotteries argued that the extent of this gambling underworld justified keeping all games of chance illegal, while proponents countered that the popularity of pastimes like “policy” would be diminished if the public had a legal alternative to them in the form of a public lottery. Mrs. Harriman and the NCLL claimed that the country lost a billion dollars a year to foreign lotteries, with another billion being siphoned off by purveyors of domestic policy games.

In her advocacy of legal lotteries, Mrs. Oliver Harriman found a kindred spirit in Washington D.C. in the person of Representative Edward A. Kenney, a Democrat from New Jersey. who proposed federal legislation to legalize lotteries in 1934 and 1935. Harriman and the NCLL also turned their attention to the New York State government in Albany, where similar moves were afoot to establish a state lottery, or at least to permit municipal ones. As these efforts were undertaken, news of the results of the Irish Hospital’s latest sweepstake drawings rippled through the press. Some 40% of the tickets were estimated to have been purchased by Americans, even as postal authorities cracked down by confiscating tickets and stubs discovered in the mails.

Although neither Kenney nor Harriman’s group made much headway in their efforts, the sheer fact that a serious debate about legalizing the lottery in New York and elsewhere could take place against the backdrop of vigorous anti-lottery enforcement at all levels of government underscored how public attitudes about gambling were in flux. A common comparison in the debate was made between alcohol consumption and gambling. If the practice of both were immutable human dispositions, then were not anti-gambling laws just as self-defeating as Prohibition had been? If the recent end to Prohibition promised to dry up the revenue stream of organized crime, then would not a legal lottery similarly provide a legitimate outlet for wagering that had previously been satisfied by playing the slots, “numbers”, “policy”, and other proscribed games of chance, especially when legal alternatives might offer their participants better odds? As one observer made the connection, “slot machines and policy games compare with honest gambling as the average bootleg whiskey of pre-repeal days compared with the present-day wet goods of a reputable (and high-priced) importer. It is honest gambling, unadulterated and aged in the wood, that is feeling the present stir in its favor.”

Mr. Harriman and the Grand National Treasure Hunt

Rebuffed by the failure of the New York legislature to approve a lottery, Harriman and the National Conference on Legalizing Lotteries turned to a broader focus on lottery advocacy that sought to promote the benefits of their legalization by, ironically, running their own lottery under the guise of the very sort of prize contest that the Post Office had under suspicion.

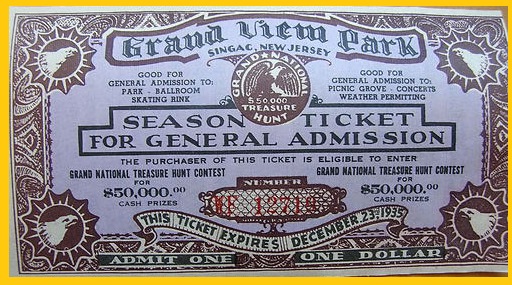

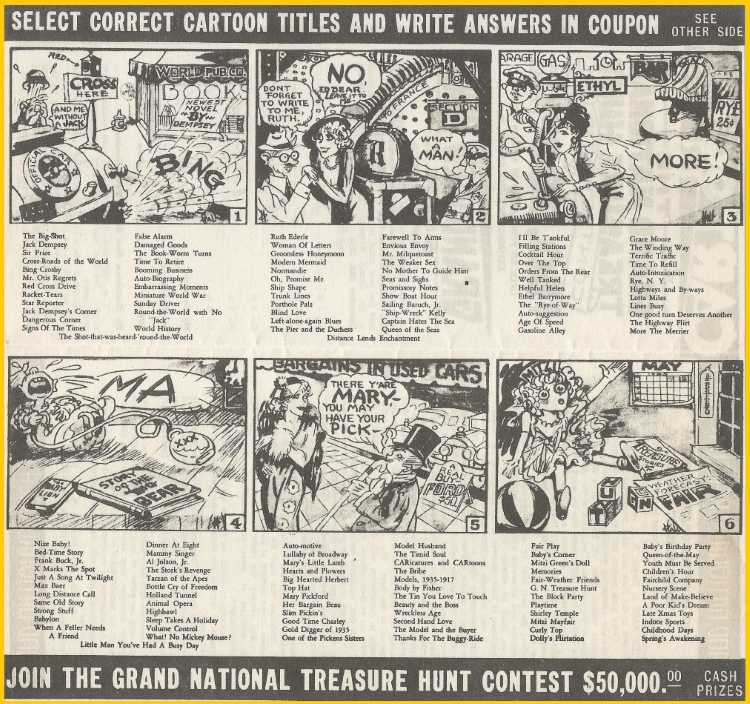

Inspiration for this came from a promotional contest called the Grand National Treasure Hunt, which was heavily advertised in New York and New Jersey newspapers beginning in late April 1935. Conducted by the Cartoon Advertising Corp. of New York City, this contest linked the purchase of admission tickets to Grand View Park, a struggling amusement park in Singac, New Jersey, to participation in a naming contest that offered a first prize of $20,000, a second prize of $5,000, and downward to a total of 206 payouts. Purchasers of $1 season tickets were each eligible to receive an informational brochure about the park that also contained eight different cartoons, each of which was accompanied by a list of possible titles. Participants in the game had to choose the “best or most appropriate” title corresponding to each cartoon, as determined by “a committee of competent judges” who would award a total of $35,000 in cash prizes. To play, people didn’t actually need to show up at the park and purchase a ticket there; they only had to send in their payment with a newspaper coupon, for which they would in return receive their admission tickets and (more importantly) the cartoon brochure. The contest closed September 3, 1935.

ABOVE: Undated (1920s-1930s) postcard depicting Grand View Park, Singac, NJ. BELOW: 1935 season ticket to Grand View Park that made its owner eligible to participate in the Grand National Treasure Hunt. (Image Source: National Museum Park Historical Association.)

The Grand National Treasure Hunt was close enough to a lottery that it attracted official attention, and in June two agents of the game were duly arrested in Times Square for selling tickets to an illegal enterprise. Fortunately for them, the magistrate hearing their case, Anna M. Kross, not only dismissed the charges but offered from the bench a ringing endorsement of Harriman’s agenda of legalizing lotteries. The principals of the Treasure Hunt, all officials of the Cartoon Advertising Corp., were operating a strictly commercial venture, but the anti-lottery movement provided them with some useful reputational cover. Assured by her legal counsel that the Post Office had accepted the Treasure Hunt's materials in the mail, Mrs. Oliver Harriman agreed to be one of the judges of its contest (that is, to decide on the best cartoon titles) in exchange for 5% of the net receipts (amounting in this case to $1,500) going to the National Conference on Legalizing Lotteries. In addition, Harriman would supervise a charity committee that would identify worthy causes that would receive a portion of the contest's receipts. Finally, in a move she would later regret, Harriman allowed the Grand National Treasure Hunt to use her name in newspaper advertisements for the contest that appeared across the country.

Cartoons used for the second Grand National Treasure Hunt Contest. This lottery was styled as a caption contest in which winners were chosen ostensibly on the basis of the phrases they selected to correspond with cartoon images. (Image Source: flyer in author's collection.)

Along with Harriman, other judges in the first contest, which ended in early September 1935, included Major Thomas G. Lanphier, Sr., an aviator and associate of Charles Lindbergh; Abe Lyman, the orchestra leader; and Jack Dempsey, the retired heavyweight boxing champion who that same year had opened his eponymous restaurant in Manhattan. Mrs. Harriman and the other individuals were, by the standards of the time, public figures whose name recognition lent to the Treasure Hunt the same cachet that celebrity participation imparts to competitions like American Idol in the present day. The winner of the first Grand National Treasure Hunt contest, a 43-year-old building porter, received his $20,000 check at a ceremony at Dempsey’s restaurant. Declaring “I will live like a millionaire for one day”, the winner averred that he couldn’t remember which cartoon titles he had chosen.

Emboldened by this success, the Cartoon Advertising Corp. set up a second Treasure Hunt, this time offering $50,000 in prizes. Tension soon arose between Harriman’s group and the Treasure Hunt because of the former’s ambitions. Though it was a commercial enterprise while the NCLL was a non-profit advocacy group, the Treasure Hunt represented a competitor to Harriman’s organization. Beginning in late June of 1935, Harriman launched the NCLL on its own series of lottery-like contests styled as “membership drives”. In early July at a luncheon at the Waldorf-Astoria, which featured Rep. Edward Kenney as the main speaker, the NCLL began a campaign to get 100,000 “members” by conducting a “slogan sweepstakes” centered around a poster designed for the lottery group by the renowned illustrator, Howard Chandler Christy. The luncheon provided the setting for Christy to unveil the poster, with the help of two children who served as models for his work. Christy’s creation used a version of his characteristic “Christy Girl” image, outfitted with angel wings and a traditional laurel wreath, who gazes with hopeful resolution out at her audience while giving succor to a pair of injured and vulnerable children, all against a backdrop of closed hospitals and unemployment lines. The poster’s overall effect was quite sentimental.

Howard Chandler Christy (left) unveils his contribution to the NCLL's slogan contest. Winners had to submit the best pro-lottery slogan suggested by this poster. The two children served as models for the poster. Mr. Oliver Harriman is second from the right. (Image Source: picture in author's collection.)

The image of Christy’s poster appeared in numerous newspaper advertisements, much in the format of the Treasure Hunt’s own publicity campaign. In the NCLL’s contest, people who sent in $1 to the organization would receive a membership certificate to the NCLL and a slogan sweepstakes entry blank that enabled them to submit their answer to the question, “what slogan does [the poster] suggest to you?” The first-place prize for the best slogan (15 words or less) was $10,000 out of 68 prizes worth $20,000 in total. In its advertising copy, the NCLL connected its contest to the drive to make the lottery “legal and aboveboard—and to keep American money for American charities.” It pointedly admonished applicants, “don’t confuse this Slogan Sweepstakes with any other kind of contest. It is sponsored by a national non-profit making organization—an honest contest and sweepstakes honestly conducted.”

Even though it advocated for legalizing lotteries, the NCLL’s contest sought to avoid tipping into the legal standard for a lottery by employing some of the same verbal prevarications that the Treasure Hunt used to defend its cartoon contest. Slogan pickers were assured, rather paradoxically, “this is a contest of skill not of chance. Remember, it’s easier ‘picking’ a slogan than it is ‘picking’ a horse. Slogan contests are usually won by people with no writing experience whatever. One of the winning slogans is just as apt to occur to you as to anyone else.” The contest closed November 30, 1935.

A few days after the luncheon unveiling of Christy’s poster, the slogan contest came under scrutiny by the New York City Police. Given the publicity it generated, and the very premise of the contest, it was impossible for the authorities not to investigate whether in fact this was against New York State law. Emil K. Ellis, the NCLL’s legal counsel, maintained that the contest only partook of the “lottery psychology”, raising funds for the pro-lottery campaign without being a lottery itself, and threatened to seek an injunction against any police interference. District Attorney Dodge was hardly going to handle a group of society ladies who had the ear of top public officials in the same way he might rough up a “policy kingpin”, and after some questioning of the group’s officials Dodge concluded that no “unscrupulous persons are using the movement for personal gain.” As long as the NCLL was not somehow infiltrated by racketeers, it was enough for the city to know that the United States Post Office was allowing its materials in the mails.

This official forbearance seemed to provide clear sailing for both Harriman’s slogan contest and the Grand National Treasure Hunt. By late summer 1935, both were operating concurrently, separate but with connections. Harriman had given her imprimatur to the commercial contest in exchange for financial support for the NCLL; Thomas Lanphier, the aviator who along with Harriman had insinuated himself into the Treasure Hunt’s stable of celebrity judges, remained an associate of Harriman’s, attending public meetings of the NCLL.

For Lanphier, his relationship with the lottery movement was most likely an opportunistic one. After serving as an aviation pioneer in the army, Lanphier’s career had entered a swashbuckling period where he barnstormed for a period of years with Charles Lindbergh. Mustered out of the army in the late 1920s, between then and the outbreak of World War II Lanphier drifted, dabbling rather unsuccessfully in a number of commercial ventures that included a widely-derided scheme for producing a “fuelless” plane motor that would be somehow powered by the earth’s magnetic field. By 1934, Lanphier was having money problems. An association with the movement to legalize lotteries might prove lucrative to him. At the very least, the efforts of Harriman’s group provided cover to commercial ventures like the Treasure Hunt.

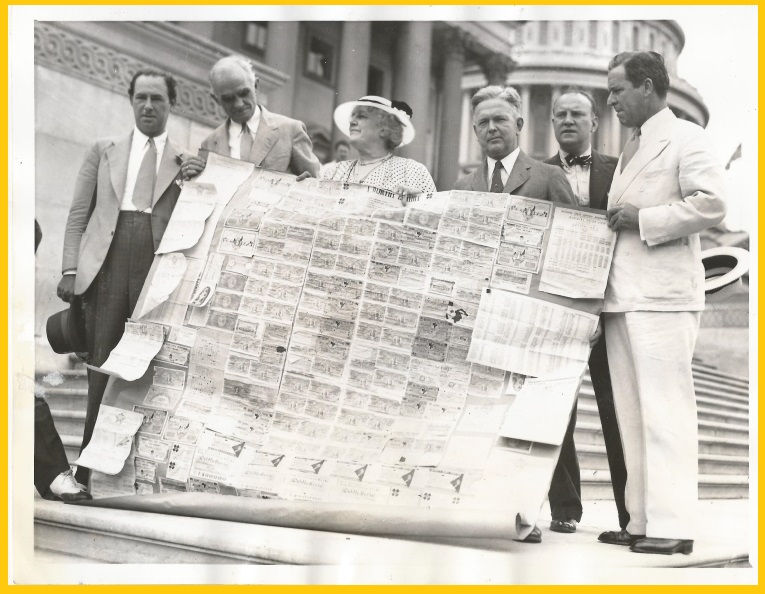

Meanwhile, in Washington, D.C., Rep. Edward Kenney’s effort on behalf of a federal lottery was proving not to be so fortunate. His bill received a hearing in late June 1935 before a subcommittee of the House Ways and Means Committee, and Kenney tried without success to attach his proposal to other bills. Accompanied by Lanphier, Mrs. Harriman travelled to the capital late the following month to deliver a pro-lottery petition to House Speaker Joseph Byrns, who met with her as a gesture of courtesy to a prominent citizen. Lanphier’s presence reflected the funding that the Treasure Hunt provided to the NCLL, but this association created some awkwardness for Harriman. In August, federal marshals raided the Grand National Treasure Hunt’s offices in Washington, D.C. and arrested its occupants on the grounds that they were operating a lottery; Mrs. Harriman’s name happened to appear on the office door. This placed Harriman in the position of defending the men arrested while distancing herself from any association with the for-profit Treasure Hunt. As the Congressional session neared its August adjournment, Kenney’s efforts to promote the lottery as a federal revenue source came to naught when Ways and Means decisively rejected his attempt to substitute his plan for the committee’s tax bill.

Mrs. Harriman goes to Washington, July 1935: Harriman (center) poses on the Capitol steps with a display of foreign lottery tickets. House Speaker Byrnes stands immediately left of her, Rep. Kenney to the right. Thomas Lanphier holds up the poster on the far right. (Image Source: picture in author's collection.)

Buoyed by the fact that the Post Office had indicated its approval of the Treasure Hunt’s cartoon contest, Harriman and her group spent the Fall of 1935 redoubling their organizing efforts. Harriman received permission from Manhattan Borough President Samuel Levy to set up a booth in Times Square to promote the lottery and to conduct a straw poll among the passers- by. In mid-September Harriman launched another membership drive, this time with the ambitious goal of pressing for the legalization of lotteries via statute or constitutional amendment in all 48 states. Harriman also formed, with some apparent redundancy, a “women’s committee” as an adjunct to the Conference’s efforts. With Harriman herself as chair, this committee comprised a roster of New York society women, including Mrs. Howard Chandler Christy and the wife of the former Governor, Alfred E. Smith.

By this time, the Grand National Treasure Hunt’s first contest had come to an end, and Harriman underscored her connection to the contest by showing up at Dempsey’s restaurant to hand out certified checks to the winners. However, her relationship with the Treasure Hunt was fraying. In response to an inquiry from the New York Better Business Bureau, which had received information from across the country that Mrs. Harriman’s name had been used in advertising for the Treasury Hunt, the Conference’s attorney Emil K. Ellis issued a statement distancing Harriman from the group. While serving on its committee to distribute a portion of its proceeds to charity, Harriman, Ellis averred, had no official interest in, or relationship with, the Grand National Treasure Hunt, which as a commercial enterprise was entirely separate from her lottery organization. I. Alfred Levy, attorney for the Cartoon Advertising Corp., countered that she indeed had given permission to use her name, quoting correspondence from Harriman dated October 1935 that she was “very happy to have been one of the sponsors and judges at your contest…I want you to feel that I am still deeply interested in your enterprise, and that I sincerely hope my sponsorship will help to continue and increase the success of your organization.” Her permission, Levy continued, was later withdrawn only after other members of the NCLL complained about Harriman’s role in sponsoring what amounted to a competitor to their contest. To the embarrassment of the NCLL, the attorney revealed that the Treasure Hunt had already paid it $1,500 under an arrangement whereby it would give the NCLL 5% of the net proceeds from Treasure Hunt contest receipts.

With the end of the relationship between Harriman’s group and the Grand National Treasure Hunt, the former’s own contest promised to provide the funding for pro-lottery advocacy that was no longer available from the latter. The Conference’s contest to choose a slogan appropriate to the Howard Chandler Christy poster closed on November 30, with some 150,000 “members”—fifty percent more than the original goal—joining the NCLL in order to get a share of $20,000 in prize money. In a ceremony at the Hotel Delmonico in late December, first prize went to Mrs. Marie Catherine Harris from Yonkers, New York. In contrast to the stylized pathos of Christy’s agitprop poster, Harris’s situation embodied the routine misfortunes of Depression-era America. A 55-year-old widow who had moved in with her father until his death in 1933, Marie Harris had lost most of her savings in a Yonkers bank failure. The first use for her windfall, she explained, was to pay off the back taxes on her family’s house where she lived with her only daughter, also widowed. As for the actual slogan that ostensibly won the contest, the flimsiness of that pretext was underscored when Harriman and her group declined to even announce what any of the winning entries had been actually submitted. Instead, the NCLL used the publicity of the winners’ ceremony to launch a new contest slated to begin January 15th, 1936. This second contest, for cash prizes worth $60,000, required contestants to rank in order of importance, from a list of sixteen possibilities given on the entry form, the ways in which profits from a government sponsored lottery might be spent (“money for hospitals”, “support widows and orphans” etc.). Again, this was ostensibly a contest of skill, not chance: “The entries which, in the opinions of the judges, list in the best order the ways of using money raised by lotteries will be awarded the big cash prizes.”

ABOVE: In this striking photo, Marie Harris (left), first-place winner of the NCLL's poster slogan contest, is congratulated by Mrs. Oliver Harriman. Note the patches on Harris's jacket and her lack of a mink pelt like Harriman's. BELOW: Flyer promoting the NCLL's second contest, this one requiring participants to rank sixteen reasons why lotteries should be legalized. (Image Source: picture and flyer in author's collection.)

A few days after the NCLL’s slogan contest bestowed its prizes, the second round of the Grand National Treasure Hunt delivered its results. This second contest was won by a 21-year- old, self-described “mystic” who received a first-place check for $25,000, delivered to her by Lanphier, who now headed the committee of judges, a motley collection of civic leaders. Over four dozen hospitals and charities were identified as intended recipients of donations from the same contest. With Harriman no longer involved, Lanphier directed the charity committee as well, bestowing a series of donations to worthy causes that generated good publicity for the Treasure Hunt. This included $2,500 to the United Hospitals Fund Drive, $200 to the Leonardo da Vinci Art School, and two ambulances to the City of New York (which a grateful LaGuardia named “Lady Luck” and “Major Lanphier”).

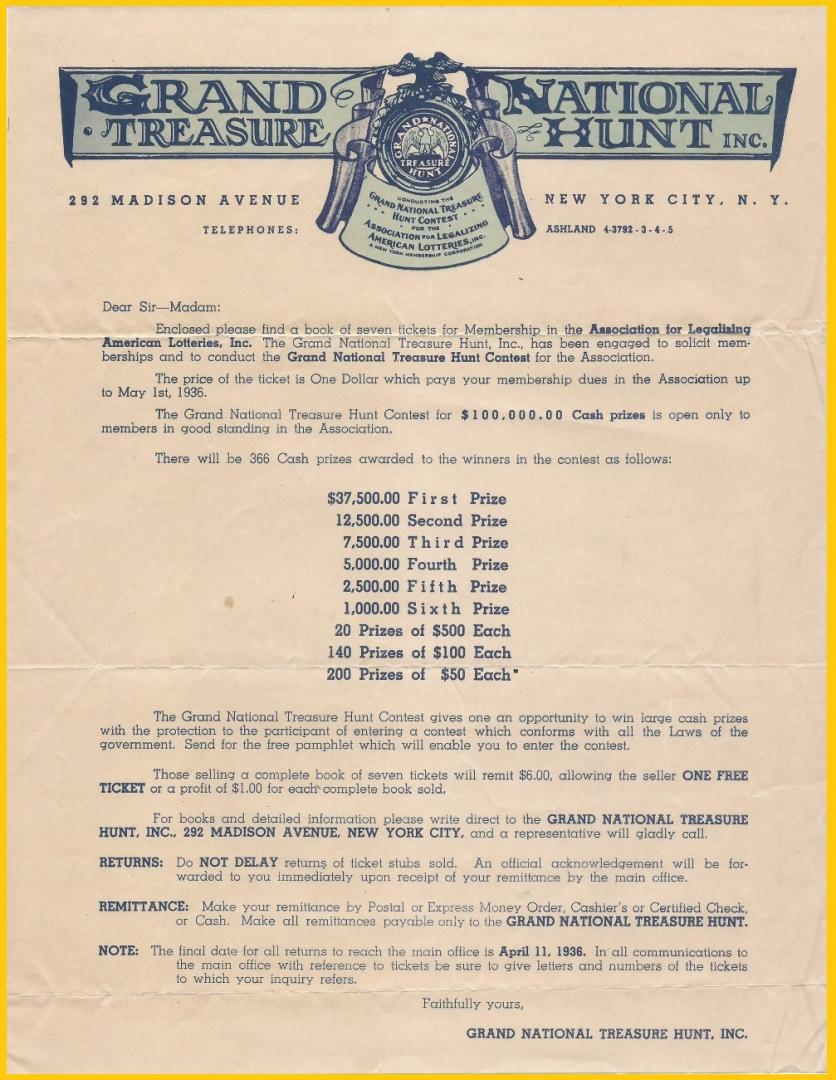

Thomas Lanphier's Association for Legalizing American Lotteries

The third round of the Treasure Hunt, whose full-page advertisements hit the papers in late January 1936, revealed an ingenious marketing twist. No longer was the contest an affair solely of the Grand National Treasure Hunt, nor did it involve admission to the New Jersey amusement park. Rather, a new entity, the “Association for Legalizing American Lotteries”, was now sponsoring the contest which, run by the Treasure Hunt, represented a “membership drive” for the new Association. Stealing from Harriman’s playbook, the advertising copy now proclaimed, “the Association has engaged the Grand National Treasure Hunt to conduct its membership drive.” As did the NCLL’s advertisements, the Association’s text also cautioned applicants to “not confuse this Association or this contest with any others.” In order to enter the contest, people had to be members of the Association; to become members of the Association, people only had to—enter the contest. Sending in the newspaper coupon with $1 in “membership dues” brought members/contestants both an entry blank to the contest (another pamphlet of cartoons for which the contestant had to guess the best captions) and a handsomely ornate ticket confirming the fact that the “purchaser of this ticket has made application for membership in the ASSOCIATION for LEGALIZING AMERICAN LOTTERIES.” The ticket, with its unique “application number”, represented payment of “membership dues” to join the Association. Members in turn were eligible to enter (for “free”) the latest Treasure Hunt contest for $100,000 in cash prizes. The contest closed April 11, 1936; the prizes would be awarded on April 30th; and the next day, May 1, membership in the Association would expire.

President of the Association for Legalizing American Lotteries was none other than Thomas G. Lanphier.

ABOVE: the same lottery ticket shown above (left); a "membership card" sent to ticket purchasers, with printed signature of Thomas Lanphier (right). BELOW: Solicitation form letter from the Grand National Treasure Hunt / Association for Legalizing American Lotteries. (Image Source: Heritage Auctions; letter from author's collection.)

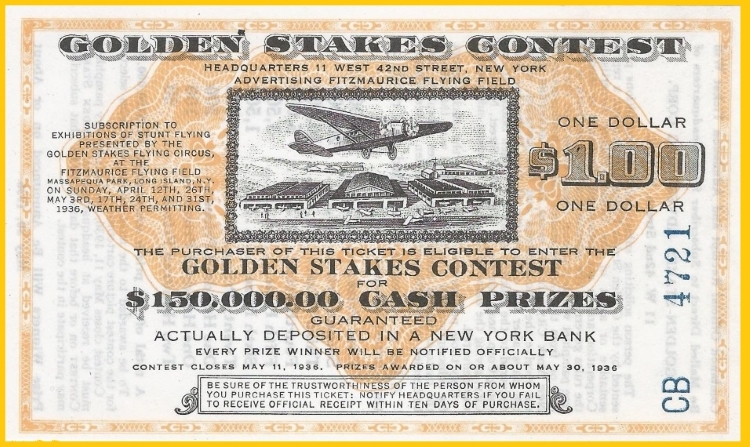

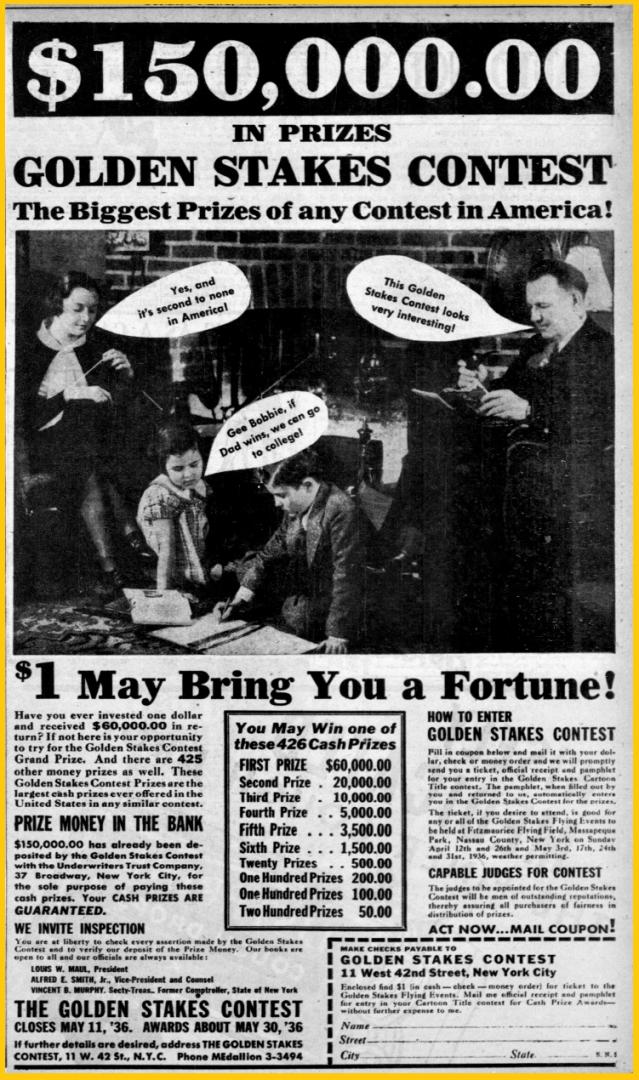

Confident that the Post Office’s earlier forbearance of the previous Treasure Hunt contests implied a similar attitude towards this latest round, the new Association acted aggressively. Its promoters challenged the State of New Jersey to rule on the legality of the contest by arranging for a Bergen County detective to arrest a commission salesman offering one of the tickets in order to get a test case in the courts. Unlike the NCLL, Lanphier's Association not only solicited "memberships", but recruited a sales force to sell its tickets. As the solicitation letter pictured above promises, any seller of six tickets would get to keep the proceeds of a seventh. Later in February the field got more crowded with the advent of a third scheme, the Golden Stakes Contest, which promised $150,000 in cash prizes to be given out based on the best results of yet another round of cartoon captioning. Like these other contests, the serial-numbered tickets themselves pretended not to be the instruments for participation. Rather, they were “subscriptions to exhibitions in stunt flying presented by the Golden Stakes Flying Circus”, whose performances at Massapequa Park in Long Island were scheduled for Sundays between April 12th and May 31st. Winners of the cartoon contest would be announced at the conclusion of the exhibitions. Golden Stakes was fronted by Alfred E. Smith, Jr. son of the former Governor and whose mother served in Mrs. Oliver Harriman’s lottery campaign.

ABOVE: A "Subscription to Exhibitions" ticket for the Golden Stakes Flying Circus. Ticket purchasers entered into a separate cartoon captioning contest. BELOW: "Gee Bobbie, if Dad wins we can go to college" --one of many newspaper ads for the Golden Stakes Contest. This was shut down by the Post Office in April 1936. (Image Sources: ticket in author's collection; New York Daily News, March 8, 1936.)

It is unclear how resentful Harriman was of Lanphier’s new status, or how sincerely Lanphier took his presidency of the Association, which appeared to an utterly contrived ploy to re-create the cover provided to the Treasure Hunt by its previous association with Harriman’s group. Both Harriman and Lanphier appeared in Albany at the beginning of the 1936 legislative session, where another, unsuccessful, push was underway to amend the state’s constitutional prohibition against lotteries.

By April 1936, however, all three schemes—the NCLL’s ranking contest, and the cartoon contests run by Lanphier and Smith—ground to a halt as the Post Office finally pivoted in opposition. All three were cited by the Post Office to show cause as to why they should not be banned as illegal lotteries. In addition, the Treasure Hunt and Golden Stakes operations (but not Harriman’s) were labeled “frauds” by the Post Office, ironically because of their use of application/membership “tickets”. The Post Office argued that not only were they illegal lotteries, but the tickets themselves represented evidence that the promoters had misrepresented their contests on their own terms. In each case, a cartoon contest implied that each contestant’s entry produced one, and only, one, possibility for divining the “correct” captions from the judges’ point of view. In contrast, providing a serialized ticket with each payment signaled to contestants that they could accumulate multiple tickets, in order to improve the odds of winning a prize. This, the Post Office reasoned, meant that the promoters must have been tricking their clientele into overbuying by insinuating that the contest was actually a lottery, when the legality of their enterprises required that they deny their character as lotteries. The contradiction was inescapable. Denied the use of the mails, both operations were shut down.

The “selection sweepstakes” sponsored by Harriman’s National Conference on Legalizing Lotteries made no use of lottery-like tickets, and thus escaped this trap. The Post Office nonetheless pursued charges that it was a lottery, based upon the more conventional argument that a contest involving rank-ordering the sixteen reasons why lotteries should be legalized was inherently impervious to skill. Contest judges, for their part, could only be guided by their policy preferences with respect to how the priorities should be ranked; there was no possibility of any single exercise of judgment that would produce a rank ordering objectively superior to another. Given this indeterminacy, the only basis upon which contestants could do well would be by knowing in advance the judges’ own priorities and adjusting their submissions accordingly. In the absence of these unknowable facts, any submission that might be correct could only be so by chance. The NCLL endeavored to reverse this decision, and it was not until March of 1938 that a ruling by the D.C. Appeals Court put a final end to these efforts.

Conclusion

With the D.C. court’s decision, the National Conference on Legalizing Lotteries was dealt a severe blow that led to the group falling inactive. Had it been more careful in the structuring of its contest and, more importantly, had its reputation not come under a cloud thanks to its association with Lanphier’s business, the NCLL might have continued on without provoking the ire of the Post Office. Even by themselves, the slogan contest and the selection sweepstakes represented mischievous challenges to a legal prohibition which the group (as reflected by its very name) aimed to repeal. In contrast, even if for-profit gift enterprises like the Treasure Hunt were in fact lotteries, they obviously sought to avoid any association with the word “lottery” in order to minimize the danger of suppression. The NCLL staged contests both to raise money for its lobbying activities and precisely in order to show the public that so-called “pious lotteries” dedicated to social welfare or other charitable ends deserved different legal treatment than lotteries undertaken for profit. Thus, the publicity generated by the games themselves tended to create their own legal danger.

In view of the official tolerance shown towards the first two Treasure Hunts and the NCLL’s slogan contest by state and federal officials, it was not unreasonable for them to assume that further contests would be permitted. After all, as a prominent society woman, Mrs. Oliver Harriman had the sympathetic ear of city officials who themselves came near to approving their own municipal lottery, and she and her confederates otherwise enjoyed a practical legal immunity that might not have been available to actual policy racketeers.

Most likely it was the precedents implied by money-making schemes like the Grand National Treasure Hunt, the American Association for Legalizing Lotteries, and the Golden Stakes contest that goaded the Post Office into taking enforcement action in early 1936. Once it was no longer merely a matter of one non-profit group staging a legally-dubious contest for demonstration effect, but multiple commercial enterprises ambitious to scale up their contests, the Post Office had no choice but to reverse its previous approval of their materials in the mails. In particular, Lanphier’s cynical invention of his own sham pro-lottery group invited the Post Office to regard Harriman’s in the same light as well. Lanphier’s miscalculation seems to have lay in his assumption that, if the Grand National Treasure Hunt had bought official goodwill by making charitable donations out of its proceeds, it would only solidify its status by associating itself with an organization whose name was quite similar to that of Mrs. Harriman’s group. Above all, it was probably the use by both Lanphier and Alfred Smith Jr. of membership applications tricked up to look like lottery tickets that provoked fraud charges from the Post Office. The Post Office’s attitude seemed to be, if you are dealing in paper slips that look like lottery tickets, then you must be running a lottery.

The defeat of the NCLL did not represent the end of Mrs. Harriman’s interest in lotteries. Later in 1938, she embarked on an entirely separate scheme to run a large charitable lottery in New Mexico, plans that fell apart by 1940 when she and her partners were charged and prosecuted for the transport of lottery paraphernalia across state lines. Rep. Edward A. Kenney’s efforts on behalf of a federal lottery, unsuccessful in 1933, 1934, and 1937, came to an end with his accidental death in January 1938, when he fell out of his sixth-floor hotel window in Washington, D.C. For Kenney, his involvement with lotteries ended with just bad luck.

REFERENCES

Bergen Evening Record (Hackensack, NJ), January 27, 1938 (Kenney obituary).

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, April 25, 1935 (Grand View Park advertisement).

Campbell, Colin P., “Advertising Schemes and the Lottery Law” The Virginia Law Register 2 (July 1916), pp. 178-185.

Coleman, Marie, “The Irish Hospitals’ Sweepstakes in the United States of America, 1930-1939” Irish Historical Studies 35 (November 2006), pp. 220-237.

Ezell, John Samuel, Fortune’s Merry Wheel: The Lottery in America (Harvard University Press, 1960), esp. chs III-IV.

The Herald Statesman (Yonkers, NY), December 21, 1935.

The Morning Call (Paterson, NJ), February 6, 1936.

National Conference on Legalizing Lotteries v. Farley, Postmaster General 68 App. D. C. 319 (1938).

The New York Daily News, January 15, 1935; March 29, 1935; June 25, 1935; October 27, 1935; February 16, 1936, March 8, 1936.

The New York Times, April 22, 1934 (quote, “slot machines and policy games...”) November 28, 1934; January 10, 1935; March 28, 1935; June 29, 1935; July 3, 8, 9, 12, 17 (D.A. Dodge quote, “unscrupulous persons…”); July 19, 27, 1935; August 11, 14, 1935 (Harriman quote, “surely it is better…”); August 18, 1935; September 16, 19, 21 (porter’s quote, “I will live like a millionaire for one day”); September 25, 1935; November 24, 1935 (I. Alfred Levy quote); December 18, 21, 24, 1935; January 25, 1936; February 20, 1936; March 12, 1936; April 5, 7, 29, 1936; March 18, 1938; March 29, 1950 (Harriman obituary); October 11, 1972 (Lanphier obituary).

Pickett, Charles, “Contests and the Lottery Law” Harvard Law Review 45 (1932), pp. 1196-1219.

Seidman, Joel I., “Lotteries for Public Revenue” Editorial Research Reports (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 1934).

The Washington Post, February 28, 1928 (Lanphier’s “fuel-less” airplane); July 27, 1935; August 14, 1935