The Origins of Poll Parrot Shoe Money

Introduction

In an earlier era when the United States economy was oriented more towards industry rather than services, different parts of the country were known for specializing in the production of certain goods, reputations that faded when that production shifted elsewhere. For about seventy-five years until 1950, St. Louis was a center for the country’s shoe industry. One company in particular, the Roberts, Johnson & Rand Shoe Co., emerged as one of the largest shoe manufacturers in the world, for its time. Of its various footwear lines, Poll Parrot Shoes for children grew to become a nationally recognized brand thanks in part to a multifaceted marketing campaign conducted by its corporate owners.

One aspect of this campaign was the use of a premium system known as Poll Parrot Shoe Money. For nearly twenty-five years, Roberts, Johnson & Rand blanketed small towns across the country with its currency-like coupons, targeting not the adults who paid for the shoes, but the children who wore them. This article examines how Poll Parrot Shoe Money worked. Although the Poll Parrot shoe brand itself has been defunct since the 1980s, supplies of its Shoe Money (along with a welter of other advertising ephemera) persist as residues of the commercial contest once undertaken over how America’s children would be shod.

The Rise of the St. Louis Shoe Industry

The beginnings of shoe production in St. Louis and its environs date to about 1870. Drawn to its burgeoning supply of cheap immigrant labor, particularly from Germany, shoe manufacturers began to set up shop there, soon consolidating into such enterprises as the Brown Shoe Co. (1893) and the Giesecke, D’Oench and Hays Co. (1898). The latter was in turn taken over by the Friedman-Shelby Shoe Co., itself established in 1906. Two brothers, Jackson and Oscar Johnson, had operated a shoe business with a cousin, Frank Rand, in Memphis before relocating to St. Louis in 1898. There, the trio added two partners, John and Eugene Roberts, to form the Roberts, Johnson & Rand (RJ&R) Co. In 1911 the company merged with the Peters Shoe Co. and renamed itself the International Shoe Co. The following year ISC acquired Friedman-Shelby. Thereafter, both RJ&R and Friedman-Shelby continued operating as independent divisions, retaining their own shoe brands within the larger enterprise.

After the turn of the century shoe production took off in St. Louis, particularly as new technology made shoemaking less of a skilled occupation, which encouraged production to relocate there from higher-wage New England. By 1905 St. Louis was producing one-sixth of all shoes made in the United States. RJ&R was known for exploiting child labor, and its new parent International Shoe Co. also acquired a reputation for being aggressively anti-union. From its beginnings ISC sought to reduce its labor bill by relocating factories away from St. Louis to rural Missouri and Illinois, where it had some four dozen by 1915. ISC benefited from government military contracts during World War I, and during the 1920s produced great returns for shareholders thanks to its enthusiasm for cutting labor costs. It also helped that hemlines went up, resulting in a boon to the demand for women’s shoes. Through growth and consolidation ISC emerged as the largest shoe manufacturer in the world, a status it enjoyed for several decades.

The Poll Parrot Brand and its Shoe Money

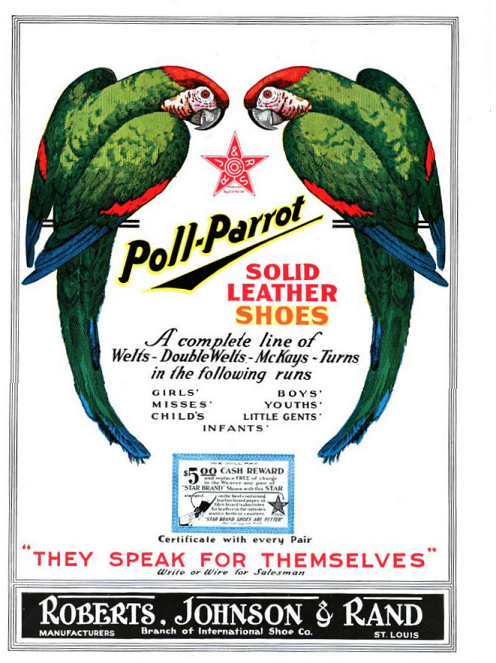

There are different accounts of the origins of the “Poll Parrot” shoe brand. In one version, the brand was named after a certain “Paul Parrott”, who had been manufacturing shoes under the Pol Parrot name in St. Louis since 1922, and had been bought out by ISC in 1928. According to another account, the company acquired the brand by buying out another St. Louis manufacturer, Parrot Shoe Co, in 1925. Whatever the case, the Roberts, Johnson & Rand division of International Shoe had already published notices in specialty publications announcing the brand as early as 1921, as a supplement to its existing Star Brand shoes (see image); by the next year, the Pol Parrot line of children’s footwear was being advertised in newspapers across the country.

Notice of Poll Parrot Shoes published in the Boot and Shoe Recorder, November 26, 1921.

In adopting the Poll Parrot symbol for its children’s line, International Shoes was only following a marketing strategy pioneered by another St. Louis-based manufacturer and chief competitor, the Brown Shoe Co., which in 1903 acquired a license to use the name and image of the cartoon character Buster Brown (and his dog Tige) as a mascot for its own children’s shoes. Other local competitors responded with similar branding moves. The Giesecke-D’Oench-Hays Shoe Co. trademarked the “Red Goose” figure in 1906, while the Peters Shoe Co. had jumped into the trend even earlier with its “Weatherbird” character in 1901. Both the Red Goose and Weatherbird characters were retained after both brands came under the ownership of the International Shoe Co.

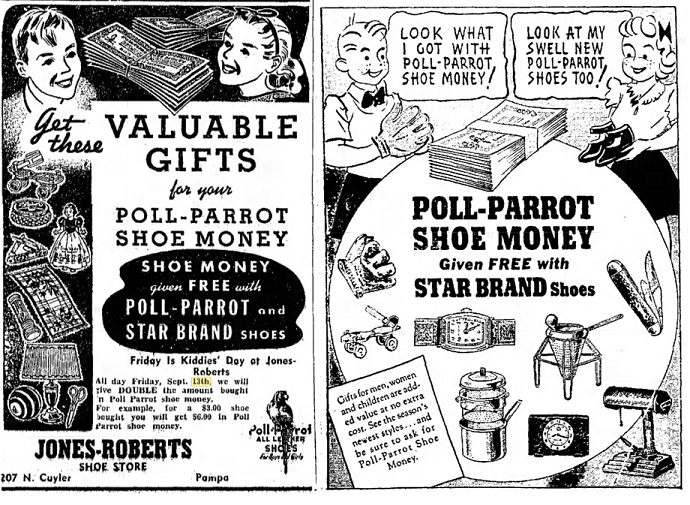

Some ten years later, newspaper advertisements run by local shoe stores in different parts of the country began announcing the issue of Poll Parrot Shoe Money to their customers. Coming in late 1933 and at the depths of the Great Depression, it is tempting to think of these issues as part of the wave of scrip that washed over the land during these years, but Shoe Money was simply another premium marketing device to capture customer traffic. Although the dismal economic climate was certainly not good for ISC’s business, even in a depression people had to put something on their feet, so the company managed. Perhaps the timing of Shoe Money’s introduction played upon the nation’s depression-era flirtation with scrip and other emergency currencies. Unlike other profit-sharing schemes popular at the time, the premiums associated with Shoe Money appealed not to the adult spenders but to the kids who were to wear the shoes. Indeed, the text on the notes clearly targeted the children, who were exhorted to “save this Money and ask your family and friends to save it for you.”

In these two advertisements appearing in newspapers from Pampa, Texas (1940) and Llano, Texas (1941), childen were clearly intended to be the recipients of Poll Parrot Shoe Money.

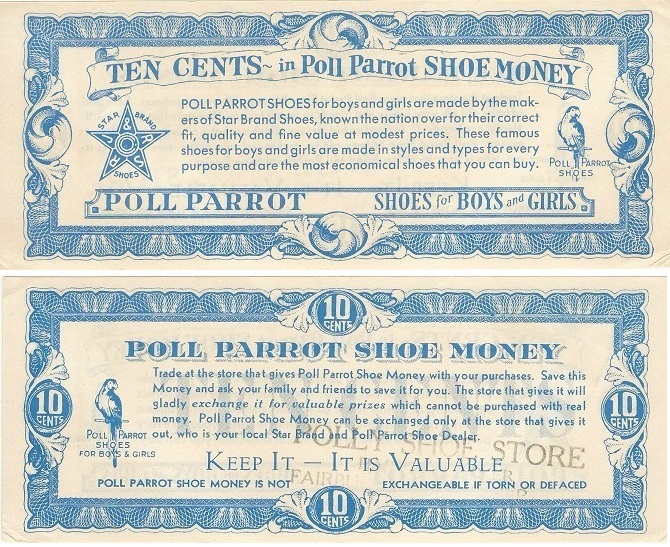

While no administrative details seem to exist as to how Poll Parrot Shoe Money was managed, the arrangement seems to have been the following. Supplies of the various Shoe Money denominations were provided by the manufacturer to individual stores, which invariably counterstamped the notes, more or less haphazardly, with their names and locations. Some retailers did seem to have taken the trouble of having this information printed on their notes with some care. Stores paid them out, to the dollar and cent, in the amount of a purchased item’s cost. As the notes instructed their bearers, “the store that gives it will gladly exchange it for valuable prizes which cannot be purchased with real money.” Instead of directing holders of the notes to redeem them by mail using a catalog, they were simply to bring their accumulated supplies back to their local stores. “Poll Parrot Shoe Money can be exchanged only at the store that gives it out, who is your local Star Brand and Poll Parrot Shoe Dealer.”

A blue ten-cent piece of Poll Parrot Shoe Money, with a stamp applied by the "Polly Shoe Store, Fairbury Nebraska". (Image source: author's collection).

Whether the inventories of gift premiums were financed by the individual stores or by RJ&R itself isn‘t known, but the sort of “valuable prizes” on offer were clearly intended for a juvenile clientele. In September 1933, the M & O Bootery in Oelwein, Iowa printed in the local newspaper a list of nineteen items for which the Shoe Money could be redeemed. These included a baseball glove ($35.00 in Shoe Money), football and roller skates (both $37.50), and a doll ($50.00). Given that this same store was advertising a pair of boys’ Oxfords from only $1.75 to $2.95, kids would have to go through a massive amount of shoe leather to get enough Shoe Money to pay for those prizes, unless families pooled their supplies across multiple purchases, which is precisely what premium marketing plans like this aimed to encourage.

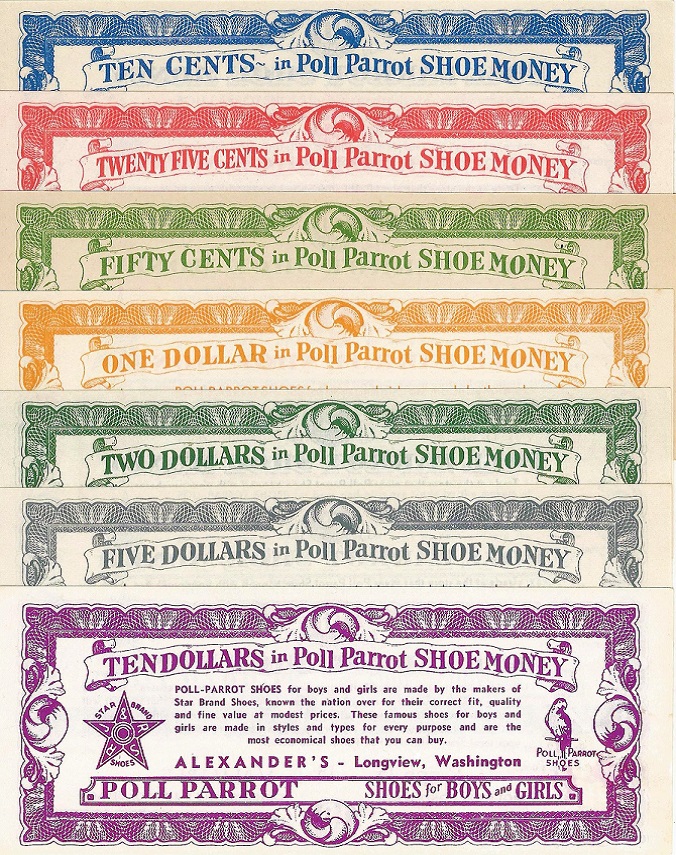

There are no great stylistic differences to distinguish between the fronts and backs of these notes. One side features the denomination printed in a banner at the top, with two logos to the left and right of the text. To the left is a five-pointed star, the emblem of Star Brand Shoes, containing the letters “RJ&RS”, which stand for Roberts, Johnson, & Rand Shoes, the division of International Shoe Co. In the other logo sits the Poll Parrot bird upon its perch. On the other side of the notes the bird again appears, to the left, while the text and field are framed by the denomination printed on the four edges of the note.

While the features of Poll Parrot Shoe Money were crude and simple enough, requiring no sophisticated security printing capacity, the overall effect might have been impressive to the average child, as the stuff definitely looked more official than mere play money. In general appearance it compared favorably to other premium coupons of the era, such as those issued by the United Profit Sharing Company. Shoe Money appeared on plain paper in 10 ¢, 25 ¢, 50 ¢, $1, $2, $5, and $10 denominations. Apart from these values, the text and design of the notes were otherwise identical, with only the color being the distinguishing feature from one note to another: 10 ¢ (blue) 25 ¢ (red) 50 ¢ (green) $1 (yellow), $2 (olive) $5 (gray), and $10 (purple) denominations. Lacking any dates, serial numbers, or printer’s imprints, it is otherwise impossible to say when, where or by whom these were made.

All denominations of Poll Parrot Shoe Money. Note the name of the shoe store, Alexander's, in Longview, Washington printed on the ten-dollar note. (Image source: author's collection)

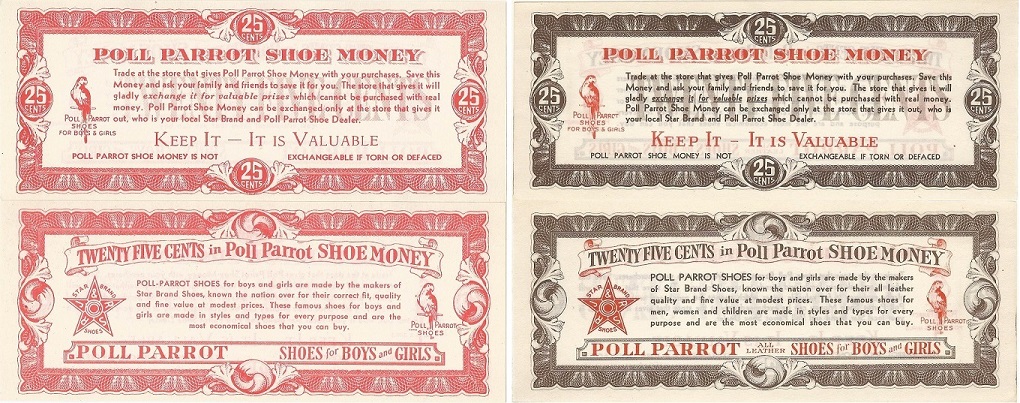

At the very least, Poll Parrot Shoe Money appears to have been issued in two varieties: one, entirely monochromatic by denomination (pictured above), the other in which the color scheme of each note is broken up by the use of red ink to print certain portions of the text. In this second variety, the star and parrot logos on both sides are printed in red, as are other phrases. In the case of the 25 ¢ denomination, which in the first variety was already entirely red, this second variety of that note is brown instead , with red printing. One other minor difference between the two varieties is the presence of the words “all leather” in the phrase “Poll Parrot All Leather Shoes for Boys and Girls” The monochromatic note variety lacks the words “all leather”. Which variety came first is unknown, though given the increasing use of synthetic materials in modern clothing, it is tempting to view the “all leather” version of Shoe Money as the earlier one.

The two varieties of Poll Parrot Shoe Money are evident in these two twenty-five cent notes. Apart from the color differences, the variety on the right includes the words "All Leather" in the banner beneath the Star Brand emblem. (Image source: author's collection).

First issued in 1933, Poll Parrot Shoe Money continued in use as a premium marketing scheme in shoe stores across the country for a good twenty-five years. It was administered in a rather decentralized fashion. If supplies of the Shoe Money itself came from the manufacturer, the stores were obliged to manage and redeem the premiums on their own premises. As the store in Oelwein, Iowa, advertised to its younger patrons in 1933, “See these prizes in our windows”. While Shoe Money was regularly mentioned by stores in their local newspaper advertisements, national campaigns for the Poll Parrot brand, appearing in such publications as Life or Good Housekeeping, never refer to the premiums, leaving it to individual stores to choose whether or not to participate. As a marketing device, the intent of Shoe Money was pretty clear. Although it was a manufacturer of national scope that advertised nationally to increase brand awareness, International Shoes also confronted a fragmented retail market in which independent stores carrying the Poll Parrot line were supported by a premium plan that encouraged kids (and their paying parents) to become repeat customers.

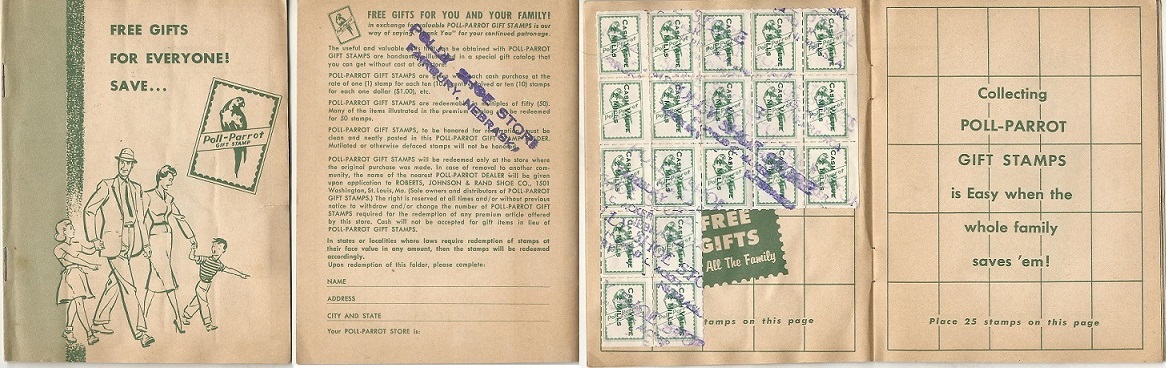

Buckner-Ragsdale Co., a fixture of the retail scene in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, provides a nice illustration of the longevity and evolution of the premium program. The clothier’s branch in the nearby town of Sykeston faithfully advertised Poll Parrot Shoe Money in the local newspaper for over thirty years. By the late 1950s, RJ&R began phasing out the use of its distinctive currency, replacing it with a trading stamp program that provided for the stamps’ redemption through a premium catalog instead of at the stores themselves. Beginning in January 1959, Buckner-Ragsdale began giving out stamps in lieu of scrip. As of November 15, 1966, the retailer announced that it was discontinuing the issue of stamps as well.

Poll Parrot "Gift Stamps" replaced the use of Shoe Money in RJ&R's premium program by the late 1950s. Use of stamps ended sometime in the late 1960s. (Image source: author's collection).

As widespread as its Shoe Money appeared throughout the land, as a marketing effort this was only one element among the company’s wider strategy to win the hearts and minds (and soles) of young consumers. Over the years, Roberts, Johnson & Rand littered the country with a variety of kid-oriented tchotchkes—noise clickers, spinning tops, whistles, puzzles, games, hats, coloring books, coin banks, pinback buttons—all bearing the Poll Parrot emblem. In 1932, the company sponsored a national contest to give away a Shetland pony named “Bimbo” to the child who wrote the best thirty-five word essay on the virtues of Poll Parrot shoes. It also made use of radio, in particular syndicating its own show, The Cruise of the Poll Parrot, a nautical adventure that was broadcast for four years starting in 1936. By the 1950s, RJ&R forged marketing ties with popular television figures like Howdy Doody, who also appeared in comic book series featuring the company’s talking bird.

In its sales gambits over the years, RJ&R simply mirrored the moves of its competitors. It some ways, the various children’s shoe brands were always chasing the Brown Shoe Co., which had succeeded in turning Buster Brown and Tige into the best-known corporate character duo. In addition to its own repertoire of children’s knick-knacks, the Brown Shoe Co. developed Buster Brown and Tige to great effect in various mass media. It also put out its own kid’s currency, Buster Brown Bucks, although apparently not at all on the scale of Poll Parrot Shoe Money. The Friedman-Shelby division of ISC, home of the original Giesecke-D’Oench-Hays brand “Red Goose” shoes, made use of its own “Red Goose Money” in a program similar to RJ&R’s, using coins however rather than paper scrip.

The End of the Poll Parrot Brand and of the St. Louis Shoe Industry

International Shoe Co. did very well during the Second World War, again thanks to army footwear contracts, and St. Louis remained a center of American shoe production until the mid-twentieth century, after which regional employment in the industry entered a steady and permanent decline. As was occurring in many other industries, by the 1960s cheaper imports would become an increasingly competitive challenge to American shoe manufacturers. Factories closed as shoe production left the city and its environs, though companies like ISC retained the St. Louis address as their corporate headquarters. During the 1950s, like other shoe companies ISC diversified into the retail end, as well as into apparel and the broader consumer furnishings market. By the early 1960s, corporate leadership at ISC had finally passed out of the hands of the original Johnson, Roberts and Rand families. Reflecting its more diverse business, the company, now a conglomerate in the managerial fashion of the time, renamed itself INTERCO in 1966.

Throughout all these changes, Poll Parrot persisted as a venerable brand of children’s shoes. Poll Parrott Shoe Money dropped out of American newspaper advertising by the late 1950s, as did the stamp program by the mid-1960s. The Poll Parrot brand continued to be advertised for sale through the late 1980s, but disappeared from view at about that time. The Red Goose brand seems to have been discontinued in the 1970s. In corporate history, the decade of the ‘80s was notorious as the era of junk bond-fueled leveraged buy-outs, and INTERCO stumbled in an attempt to ward off one such hostile takeover, declaring insolvency as a result in 1991. Emerging out of bankruptcy as Furniture Brands International in 1996, the new company no longer had anything to do with shoes, and met its own squalid corporate death some years later. The Brown Shoe Co. lived on until 2015, when it was bought out by a Wisconsin firm, though the Buster Brown brand, unlike its earlier rivals, still survives.

..........

REFERENCES

Boot and Shoe Recorder, November 26, 1921, pp. 33-34.

Clark, C. R. and Robert B. nd. Red Goose Money: A Catalogue of Red Goose Presidential Coins, Premium Money and Play Money.

Daily Standard [Sykeston, Missouri], various dates 1933-1966.

International Directory of Company Histories. 2001. “Furniture Brands International” Vol 39 (St. James Press).

Keenoy, Ruth Nichols. 2016. “Shoe Industry of St. Louis, 1870-1980” Next NGA West (December 14).

Llano [Texas] News, April 3, 1941.

Oelwein [Iowa] Daily Register, September 19, 1933.

Pampa [Texas] Daily News, September 12, 1940.

Smith, Kristine Runberg. 2005. “Following Buster Brown’s Footstep: Leading Families into the Middle Class Consumer Society” PhD Dissertation, St. Louis University.

St. Louis [Missouri] Post-Dispatch, August 8, 1999.