Bringing Vignettes to Life

Ray Sugden and the Mystery of "Tampa's Mystery Buck"

Introduction

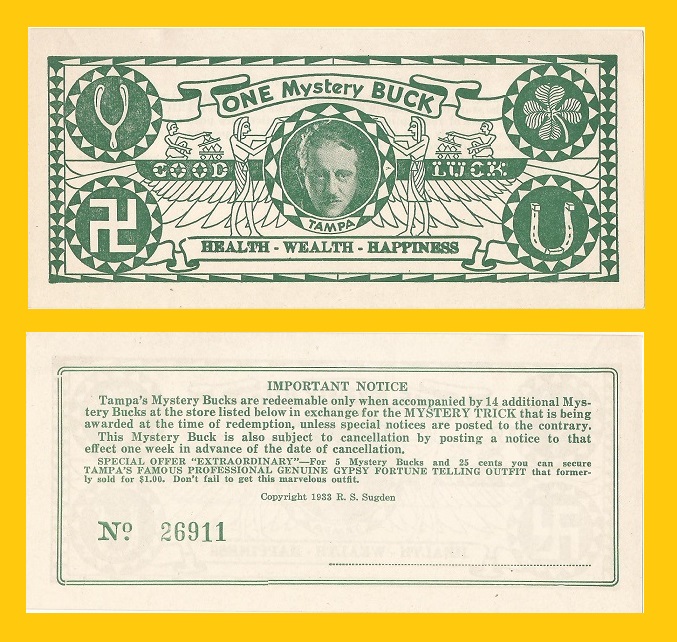

In June of the year 2000, notice appeared of a curious advertising note in the pages of Fun Money, the quarterly newsletter of an offbeat collector organization, The American Play Money Society (if any organization deserved to exist, it was one with a name like that). Printed in simple green ink, the note is denominated “One Mystery Buck” and features on its obverse a brooding, mustachioed visage labelled “Tampa”, the eyes staring directly forward with hypnotic intensity. Its portrait framed by ancient Egyptians motifs and surrounded further by conventional symbols of good luck, the note wishes its possessor “Health, Wealth, and Happiness”.

On its reverse, the note is utterly unadorned except for the terms of an advertising offer and a serial number. “Tampa’s Mystery Bucks” promises a “MYSTERY TRICK” when fifteen of them are redeemed at a participating store. An additional offer promises “TAMPA’S PROFESSIONAL GENUINE GYPSY FORTUNE TELLING OUTFIT” in exchange for five Mystery Bucks and 25 cents. The whole arrangement is copyrighted “1933 R. S. Sugden.”

The "Tampa Mystery Buck"

According to the author of the notice, Randy Partin, the note is clearly a promotional coupon for magical novelties issued in the year 1933, but who is the man in the portrait, and where were these advertising offers available? Without any redemption address given on the note, Partin deduced they were spendable at participating stores, but in some town or city of unknown location. Surmising that the portrait could be of the mayor of Tampa, Florida, or at least of a magician residing in that city, Partin consulted various Florida business directories but was unable to find a Tampa listing for anyone named Sugden. With that, the author reached a dead end. “I guess I didn’t have enough Mystery Bucks to provide me with enough good luck to find out who R. S. Sugden was.”

Randy Partin concluded with this question: “Does anyone out there have any information about these Mystery Bucks?” The answer is, after twenty years—yes, but not because of any amount of lucky Mystery Bucks. Rather, internet-based resources have simply made it much easier to chase down clues about obscure mysteries such as this. The following is the story of Raymond Sugden, a.k.a. Tampa the Magician, and his Mystery Buck.

Tampa, England’s Court Magician

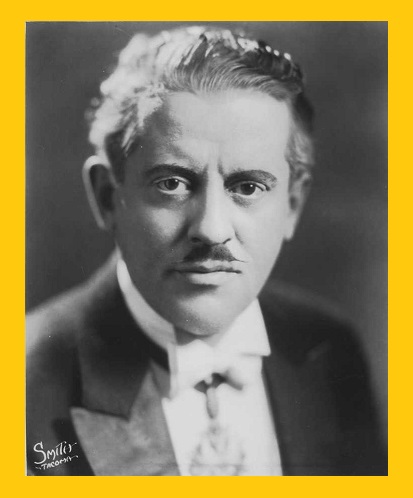

Raymond Stanley Sugden (1887-1939) was born in Lawrenceville, just outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the youngest child of nine. Details about his personal life are sketchy, in particular about how he embarked on a career as a professional illusionist. One account had it that Sugden caught the magic bug as a child after witnessing performances by the eminent American magician, Harry Kellar. Soon the youthful Sugden was assisting magic shows at carnivals, playing the role of a “plant” in the shows’ audiences.

Raymond Sugden's Publicity Photo as Tampa the Magician (Source: Ancestry.com)

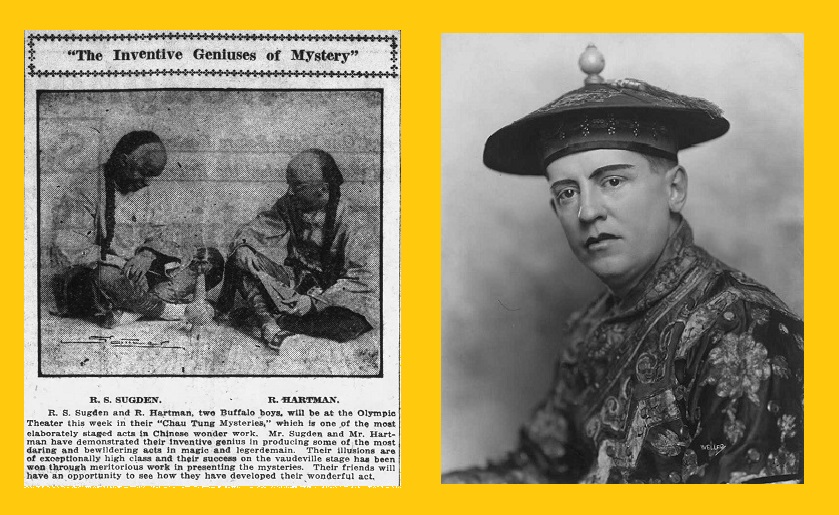

After attending Carnegie Tech (now Carnegie-Mellon University) where he studied electrical engineering and pitched for its baseball team in 1908, Sugden began working as a Pittsburgh sales representative for the cigarette manufacturer M. Melachrino & Co., Inc. Sugden married Helen Marguerite Campbell, and by 1912 the couple had two sons. Later, the job required him to relocate to Buffalo, New York. During this time, Sugden’s talent for magical tricks became more than a sideline. In 1917, Sugden teamed up with a colleague, Ray Hartman, to form a magical act called the “Chau Tung Mysteries”, in which Sugden played “Ta Yuan” and Hartman “Yong Tong”, two Chinese conjurers who regaled their audiences with a variety of sleight-of-hand tricks infused with oriental mysticism. Yellowface routines like this were common in vaudeville and burlesque performances of the time. The pair took their act to vaudeville theaters around Buffalo. Apparently both were still affiliated with the cigarette company, as they were billed as the “melachrino prestidigitators.” As the trade journal Tobacco Leaf noted approvingly, Sugden even managed to work product placements for Milo cigarettes and Blenheim cigars into his acts.

Left: Sugden & Hartman in the "Chau Tung Mysteries"; Right: Ray Sugden as "Ta Yuan" (Sources: The Buffalo Times, March 24, 1918; Ancestry.com).

The Sugden and Hartman duo came to an end when the latter was drafted into the army during the Great War. A professional magician himself, in later years Ray Hartman toured separately as Hartman and Co., reviving his own version of the Chau Tung act. In 1918 Sugden quit working at Melachrino and the family returned to Pittsburgh, where Sugden held a day job as an auto tire salesman while honing his repertoire of magical tricks. Soon Sugden was working full time as a magician, traveling with his act to small towns throughout western Pennsylvania, with his wife Helen as an assistant as well as several others. By 1924 Sugden was styling himself in his publicity as “England’s Court Magician”, although there is no evidence that he ever traveled outside the United States.

Raymond Sugden’s big break came in 1925, when he was engaged by a more prominent impresario, Howard Thurston (1869-1936), to tour under Thurston’s name and perform certain acts that were part of Thurston’s repertoire. A much bigger name than Sugden, Thurston had performed magic shows all around the world and even, in 1924, at the Coolidge White House. A protégé of the great Kellar, Thurston took over from his mentor a number of magical tricks when the older magician retired in 1908, most notably a famous act, “The Levitation of Princess Karnac.”

In addition to inheriting Kellar’s repertoire, Thurston had been developing new, technically-demanding acts that he simply could not carry out by himself. In 1923 he hired another illusionist, Harry August Jansen, to tour as “Dante the Magician” under his sponsorship. Thurston fronted Jansen working capital, public relations, and labor assistance in exchange for half of the receipts. Two years later Thurston signed a similar, ten-year contract with Sugden for a second traveling show under Thurston’s name.

Thurston’s contractual relationships with Jansen and Sugden illustrated something about the economics and culture of professional magic. Its practitioners tended to cultivate different skill sets. Some performers were particularly adept at sleight-of-hand tricks. Others, like Thurston, specialized in creating illusions based on elaborate mechanical contrivances whose effectiveness depended upon their artifice being concealed from the audience. Still others, like Harry Houdini, were known for escape artistry (Thurston had a long-running but friendly feud with Houdini over bragging rights to professional supremacy, a dispute sharpened by their disagreement over whose brand of illusionism was superior).

Because Thurston’s illusionist effects depended upon clever technology, these acts involved a much greater capital investment than the usual feats of legerdemain with cards, handkerchiefs, etc. that might otherwise reflect the skills and dexterity of individual magicians. Knowledge of how these machines were built and operated represented valuable trade secrets in their own right. A tight-knit yet jealous fraternity, professional magicians feared losing control of their secrets to competitors. Owning more acts than he could perform by himself, Thurston essentially subcontracted parts of his repertoire first to Jansen, and then to Sugden.

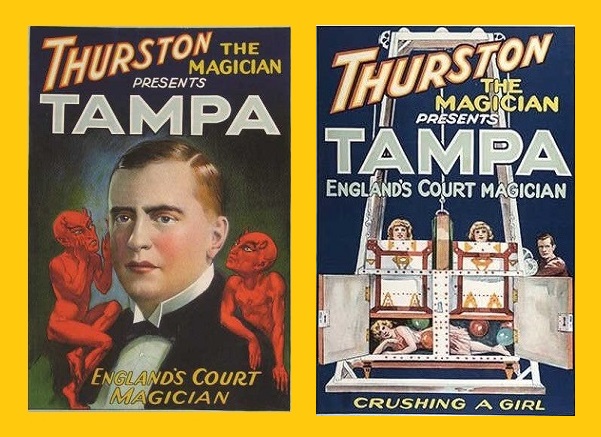

Why Thurston struck a deal specifically with Sugden is unclear, beyond the general appeal of Sugden’s reputation. Sugden did prove helpful in designing one of Thurston’s numbers, the “Hindu Rope Trick”, which at its climax required blasts of steam to conceal an assistant’s escape from view by the audience. Sugden designed the boiler that would emit the steam just at the right moment. Now in Thurston’s employ, Sugden was re-christened “Tampa, England’s Court Magician.” Thurston apparently chose the name because he had some investments in orange groves in that town, and thought the name would bring him good luck.

Performing as “Tampa”, Sugden’s profile benefited from Thurston’s greater reputation and public relations resources. The next five years represented the high point of his career, as Tampa the Magician traveled around the country, performing Thurston’s acts either in vaudeville theaters or in movie houses, where it was common in the early days of talkies to combine live performances with film screenings in a double bill. The premise of Thurston’s promotional copy was a bit patronizing, as it lauded Tampa as if he were some understudy whose talents Thurston had discovered and nurtured, and which had earned Thurston’s stamp of approval. For Sugden, though, this did not seem to be a problem, as the relationship put him before audiences that he probably never would have reached.

As Tampa, Sugden showcased Thurston’s repertoire of illusions. These included “The Levitation of Princess Yutive” ( née “Karnac” when it was Kellar’s act); “The Human Pin Cushion” (woman placed in box and seemingly skewered multiple times); the two self-explanatory acts “Crushing a Lady” and “Stretching a Woman” (pretty female assistants bore the brunt of professional magic); “Water Fountain Act” and, somewhat verbosely, “Shooting a Live Canary into a Mazda Electric Light.” In order to maintain their freshness and their audiences’ interests, these main acts were rotated over the course of Sugden’s tours. During a given performance, which might only last between twenty-five and forty-five fast-paced minutes, Sugden would fill in the time between the main illusions with a mix of his own sleight-of-hand tricks involving handkerchiefs, cards, and other small items.

Two Publicity Posters for Tampa, England's Court Magician (Source: Ancestry.com).

Newspaper reviews for “Tampa the Magician” were regularly favorable, though some sounded as if they could have been lifted from publicity copy provided by Thurston. One notice from 1928 in the trade publication Billboard said, “Tampa has a suave manner of working which helps him put over his effects, altho the act is lacking comedy relief…The act is overwhelming in its pretentiousness for vaudeville.” Sugden’s relationship with Thurston nonetheless suffered from two headwinds which ultimately brought this phase of his career to a premature end. The first came from attempts by Harry Jansen (“Dante the Magician”) to undermine Sugden’s standing with Thurston. Jansen, who Thurston had engaged two years before to showcase his magical acts before hiring Sugden to do the same, now disparaged Sugden’s talents in correspondence with his employer. In addition, Jansen alleged that the presence of Sugden on the circuit was depressing the rates that agents would pay for booking his own and Thurston’s shows.

Whether or not Jansen’s backstabbing jealousies had any truth behind them, a second factor without doubt aggravated the unfavorable economics of traveling magic shows, and that was the more general eclipse of vaudeville itself. Even before the onset of the Great Depression, changing audience tastes as reflected in the growing popularity of moving pictures diminished the opportunities for theatrical acts of all sorts. A magic show like “Tampa the Magician” was vulnerable to these changes. It was expensive to mount, involving as it did six tons of equipment and fifteen people, all of which had to be paid for and transported repeatedly, and all for the sake of an audience experience that lasted well under an hour. A show of that length was viable as long as there were enough theaters available to book it as part of an evening or matinee bill of performances, which was how vaudeville had operated. Already by the mid-1920s, Sugden had been performing in double bills with movie screenings. Now, as purely theatrical venues closed or converted entirely to picture shows, bookings for “Tampa the Magician” dried up by the end of the decade, leading a frustrated Sugden to attempt to strike out on his own tour unauthorized by Thurston, but still using Thurston's name and illusions. This proved simply unacceptable to the latter, and the relationship between the two magicians ruptured.

From Tampa, England’s Court Magician, to Tampa, the Radio Magician

The ignominious end to “Tampa the Magician” as a traveling act came in West Virginia, where by mid-1930 Sugden was scrounging for bookings, despite Thurston’s objections since the use of his name opened him to financial liability. In July, partnering with a different financial backer but still using Thurston’s equipment, Sugden had joined a canvas (tent) show in the town of Moundsville, part of a traveling carnival that was decidedly more down-market than his previous venues (Sugden’s was one of five variety acts, all orchestrated by an emcee named “Midget Mac Duncan”). Unfortunately, Sugden’s inability to pay his musicians provoked a lawsuit for back wages and a legal judgment seeking to seize the show’s props. These were rescued only after Thurston sent his brother Harry, whose strong-arm methods secured their release into Thurston’s control, leaving Sugden stranded without a show to perform. Ironically, Sugden’s professional magic ambitions seem to have ended in the same carnival setting where they began long ago when he was a teenager.

Despite the financial collapse of his tour and his falling out with Thurston, the “Tampa” moniker had become too professionally valuable for Sugden to jettison, and he continued operating under that name, as well as referencing Thurston’s, for the rest of his career. After the West Virginia debacle he never tried extensive touring again, returning to Pittsburgh where he developed a well-received radio show on WCAE sponsored by the Hankey Baking Company. Reinventing himself as Tampa the “radio magician”, he managed to translate into sound some of the visual appeal of the magical arts, particularly with programming that debunked the claims of spiritualists, practitioners of divination, and other con artists. Sugden built on his new radio presence by offering his magical talents for hire at local events. If economic depression and changing entertainment tastes had brought an end to traveling magical shows, Sugden’s talents still found him audiences at banquets, clubs, or for sales and merchandising promotions. In 1934 Sugden became a spokesman for the Pittsburgh Press newspaper, representing it in various campaigns to promote the paper’s circulation.

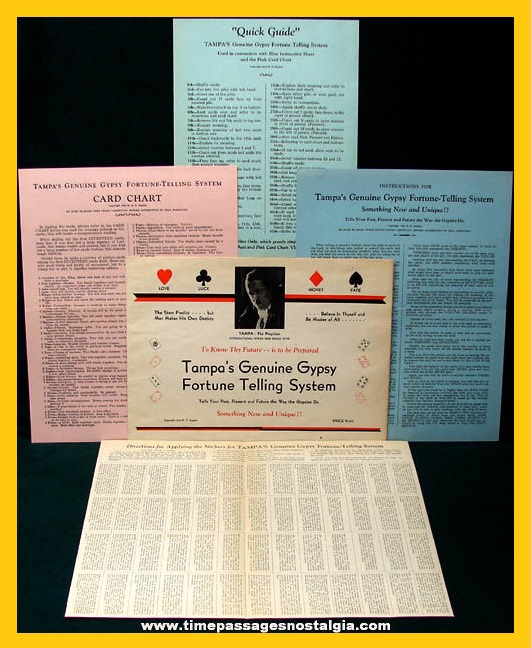

In addition, Sugden used his perch in radio to market various mail-order products relating to magic, and this is where Tampa’s “Mystery Bucks” played a role. For all of his on-air pretentions to unmask phonies, Sugden counted on a certain gullibility in his own audiences. Through his radio promotions and live performances, Sugden sold novelties like “Kolibri—Tampa’s ‘Psychic Wave’ Sex Indicator” (while this sounded promisingly off-color, the product was just a pendant whose pattern of swings purported to “tell the sex of human beings, animals, and plants”) and “Tampa’s Genuine Gypsy Fortune Telling Outfit”. Sugden distributed Tampa’s Mystery Bucks by contests on his radio show, through the Pittsburgh Press, and simply by handing them out at his live performances. From the wording on the back of each Mystery Buck it was evident that Sugden intended these notes to be redeemed at participating stores (the names of which would be printed thereon) where the proper number could be exchanged for an unspecified MYSTERY TRICK. In addition, the offer continued, five Mystery Bucks and twenty-five cents got the lucky recipient Tampa’s gypsy fortune-telling package. The gypsy “Outfit” referred to on the note was not some set of clothing, but rather an envelope containing several multi-colored pages filled with dense instructions for how a person, using an ordinary card deck, could tell “your past, present, and future the way the gypsies do.”

Tampa's Genuine Gypsy Fortune Telling System (Source: timepassagesnostalgia.com)

In these various ways Sugden nursed along his career as a professional magician. Even as he kept performing under the “Tampa” name and stressed his affiliation with Thurston in his own publicity materials, Sugden still smarted financially from the failure of their relationship. In correspondence with his erstwhile mentor, Sugden sought, without success, monetary compensation for the collapse of what was supposed to have been a ten-year contract. In a somewhat unseemly turn of events, after Howard Thurston died in 1936 Sugden sued his estate for a share of an estimated six hundred thousand dollars that would’ve otherwise gone to the widow and daughter. Sugden managed to obtain a court order for an inventory of Thurston’s estate. Weighted down by worthless mining stocks, the actual value of the estate turned out to be not much more than $20,000, and even this amount had to be reduced by, of all things, the amount of taxes owed on the Florida real estate holdings which had prompted Thurston to bestow the name “Tampa” on his protégé in the first place! Ultimately, Sugden settled his claim on the estate for a mere $1,000, plus ownership of the various apparatuses that Thurston had constructed to create his stage illusions.

Sugden himself died in 1939 at the young age of 51, from coronary heart disease. Newspapers in the Pittsburgh area ran affectionate obituaries, reflecting his prominence as a local favorite son. News of the passing of “Tampa the Magician” was picked up by the press across the country, and most notices repeated the same undoubted fictions that he had toured in Europe, performed for King George V, and that for this reason he had actually earned the title “England’s Court Magician.” Hopes that one or the other of Sugden’s sons might continue performing under the “Tampa” name (particularly Ray Jr., who had a minor entertainment career himself under the name “Ray Styles”) came to naught, and a warehouse full of Sugden’s magical paraphernalia, much of it acquired from Thurston’s estate, gathered dust for over thirty years until it was finally auctioned off shortly before Sugden’s wife died in 1972.

While perhaps not of the rank of Thurston or Houdini, Raymond Sugden was nonetheless a gifted performer whose truncated touring career reflected the same shifting public preferences for movie entertainment that decimated vaudeville as a broader cultural pastime. By all accounts Sugden had an effective stage presence in a line of entertainment where audience rapport was an important ingredient of successful magic tricks. He gave to his community by regularly performing for relief and charity causes. He was particularly kind and generous to children in his audiences, once giving away twenty-five bunny rabbits to a juvenile crowd in 1931 (being the depression years, one wonders how many of those cute creatures actually ended up on the family dinner table). Sugden’s local esteem was such that the Pittsburgh branch (or “Ring”) of the International Brotherhood of Magicians renamed itself the “Tampa Ring” in honor of their former president, the name by which this branch of organization goes to this day.

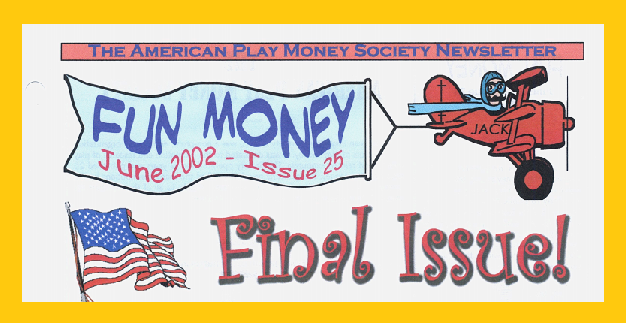

Postscript: The American Play Money Society

As for the American Play Money Society, a group with such a whimsical purpose was fated not to endure. The group dissolved on the last day of May, 2002, an early victim of the internet, whose torrent of information and abundance of collecting opportunities seemed, at the time, to diminish the rationale for an organization with such a specialized focus. First issued in 1996, Fun Money suspended publication with its twenty-fifth and final number in June 2002. As its “editor-at-fault”, Jack Phillips wrote a brief requiem for that final issue. Noting the waning circulations of newsletters generally, Phillips lamented that “the internet is probably the greatest influence on these declines since many of us now obtain the information we want virtually immediately” rather than wait for the newsletter to come in the mail. Phillips continued: “Yes, it is true that [the newsletter] can fill another need by providing good, in-depth articles on narrowly-defined subjects; however, even that can be obtained by a search of the internet and a few emails to knowledgeable sources.” Finally, Phillips revealed the sad truth: “The number of articles contributed decreased last year and we finally arrived at a point where no articles were submitted for this issue…”

Looking back, we might think that establishing a website for the American Play Money Society and its newsletter would have been the obvious way to transition the group to an online existence (and many specialty collecting niches have indeed done this); apparently this option was either too expensive or too technically demanding for a small group in the early years of the internet’s development. Nonetheless, an archive of the full run of the newsletter—where you can learn about such esoterica as Red Goose Money, Interplanetary Credits, or Baby’s Own Klikum Dollar—can be found at a legacy website here, as well as through the Newman Numismatic Portal.

..........

REFERENCES

Billboard, October 28, 1928.

Buffalo Live Wire, June 1916.

Buffalo Inquirer, April 1, 1917

Buffalo Times, April 8, 1917; March 24, 1918.

Butler [PA] Citizen, March 13, 1919.

Frank, Gary R. TAMPA: England’s Court Magician (Granada Hills, CA: Gary R. Frank 2002).

Gibson, Walter B. The Master Magicians: Their Lives and Most Famous Tricks (Seacaucus, NJ: Citadel Press, 1966), p. 159

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 5, 1930; January 11, 1937

Pittsburgh Press, January 7, 1925; August 30, 1931; September 10, 1934; July 20, 1939; September 29, 1939

Steinmeyer, Jim, The Greatest Magician in the World: Howard Thurston versus Houdini & the Battles of the American Wizards (Penguin Group 2011), pp. 262-3, 274, 300, 338-9.