Selling Solidity: Advertising Deposit Guaranties on State Bank Checks in the Early 20th Century

Introduction

Prior to the establishment of federal deposit insurance in 1933, a number of states experimented with their own deposit guaranty plans that sought to prevent bank runs. First introduced by Oklahoma in late 1907, the deposit guaranty idea was soon copied by Kansas, Nebraska, and Texas. Several years later, Mississippi, South Dakota, North Dakota and Washington adopted plans based on the Kansas and Nebraska arrangements. Seeking an advantage in their competition with national banks for customers’ deposits, state banks often advertised this protection through vignettes, devices, or other wording added to the arrangement of their checks. This article sketches briefly the experiments with state deposit guaranty plans and illustrates the ways that banks used their checks to promote the security provided by their states’ guaranty funds.

A Brief Background to Deposit Guaranty

The push for deposit guaranty laws grew out of how the 19th century National Banking System (NBS) operated. The NBS sought to standardize the nation’s currency by suppressing state banknotes with a tax on their circulation. In the dual system of national and state banks that emerged by the end of the century, the value of national banknotes were effectively guaranteed by their bond backing and the gold redemption fund held by the Treasury. State bank deposits, on the other hand, lacked such protection, even though they served the same purpose as currency when customers wrote checks against them.

In addition to their note circulations, national banks enjoyed other advantages over their state counterparts. Their larger average size and stricter regulation by the federal government meant that they enjoyed a better reputation than did state banks. Key for state banks was the prohibition of branch banking. If larger (usually national) banks were allowed to establish multiple offices to take deposits and make loans, then smaller state banks would find themselves squeezed out of their local markets. In response to these concerns most states either forbade or did not authorize branching, and the NBS permitted it for national banks only in those states that did likewise.

In this dual banking system, deposit guaranty plans could be defended as a pre-emptive defense against branching. Such plans would bolster unit banking, serving the interests of country bankers as well as the ideal of local control of finance. Larger, city banks tended to be hostile to deposit guaranties, arguing that they encouraged reckless banking.

The Panic of 1907 provided an opening for passage of the first 20th century state deposit guaranty law. Oklahoma’s Governor-elect Charles N. Haskell and the Oklahoma Bankers’ Association (OBA) argued that deposit guaranty was a prudent and conservative response to the missteps of eastern financial elites, and a bill was passed, with little opposition or debate, on December 17, 1907. Fearing a drain of deposits into Oklahoma, Governor E. W. Hoch of Kansas soon called upon the legislature to enact a similar measure: “our sister state of Oklahoma has enacted a depositors’ guarantee law, to take effect in a few weeks, jeopardizing the deposits of many of our border banks and indeed many of our interior banks, as these bankers themselves write me.” Oklahoma’s Assistant Attorney General Hinshaw even taunted, “Kansas will have to pass a bank deposit guaranty law or Oklahoma will soon have all your money”. Similar pressures to respond to Oklahoma’s new law built up on Texas’s Governor Thomas Campbell.

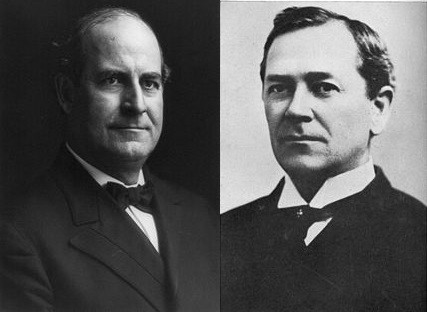

William Jennings Byan (l), Charles Nathaniel Haskell (r)

Though a bold precedent, Oklahoma’s plan was both overly-generous and meagerly funded. Oklahoma’s deposit guaranty was never a direct liability of the state, and available resources were limited to the guaranty fund itself, which was funded solely by a one percent assessment upon the deposits of participating banks. The law also required depositors to be paid in full immediately out of the ready assets of the failed banks plus contributions from the guaranty fund. As an insolvent bank’s affairs were unwound, the fund enjoyed a prior lien any recoveries. If necessary, banks would be called upon for special assessments top off the fund.

On paper, Oklahoma’s plan seemed feasible, but its execution was not prudent. The state bank commissioner rushed the qualifying examination of state institutions in order to meet a February 1908 starting date. This rush reflected the growing significance of deposit guaranty in the 1908 presidential elections. William Jennings Bryan embraced a national guaranty plan as part of his campaign against William Howard Taft. In making deposit guaranty a campaign issue, the Oklahoma experiment was crucial. Bryan proclaimed the benefits of Oklahoma’s new law, and brought Haskell into the campaign as the party’s treasurer, with the party’s campaign funds on deposit at an Oklahoma bank, highlighting the deposit guaranty plank of his campaign platform.

Meanwhile, as chair of State Banking Board, Governor Haskell sought to accentuate the efficient workings of the scheme. An early opportunity came in the case of the International Bank of Coalgate, a small bank located in the former Indian Territory. After an inspection in May 1908 revealed improper loans, the bank was ordered closed and depositors paid off immediately. Subsequent liquidations of the bank’s assets more than reimbursed the Fund, leading to accusations that a sound bank had needlessly been made a test case of the law in time for the Democratic National Convention that summer.

Oklahoma’s banking sector grew impressively under the new law. Between February 1908 and November 1910, individual deposits in state banks tripled, while the number of banks in the plan grew by nearly fifty percent. An August 1908 ruling by the U.S. Attorney General forbidding national banks from joining the guaranty plan prompted many Oklahoma institutions to convert to state charters. These conversions, and the mounting deposits in state banks, were seized upon by the plan’s supporters as proof of the wisdom of the law.

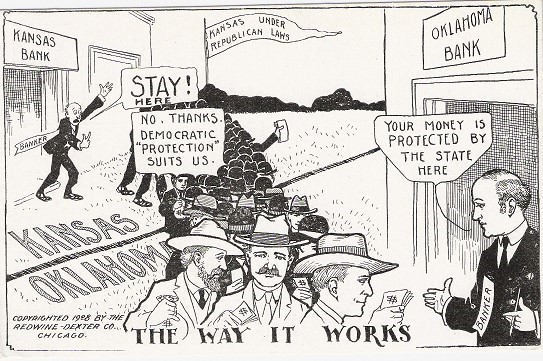

Bryan's argument in the 1908 election. (Image source: author's collection)

The Attorney General’s decision fed into Bryan’s election strategy for 1908. Once it became clear that national banks could not participate in state plans, a Democratic plank in favor of a national guaranty only became more compelling, since pitting state banks against national banks would bolster the argument for a national counterpart to state guaranties. Key to this was the spread of guaranty laws beyond Oklahoma. The advantages Oklahoma gained from its law would put pressure on other states (particularly those adjacent to Oklahoma) to enact their own laws. Ultimately, Bryan argued, the competition from a movement towards state guaranty plans would lead to the nationalization of the Oklahoma precedent.

If Oklahoma’s deposit guaranty law served as a promising vehicle for Bryan’s campaign, the involvement of Oklahoma’s Governor Haskell was less auspicious. Named as the national Democratic Party treasurer in late July of 1908, Haskell became the object of attacks regarding his relationship, through his law practice, to an affiliate of Standard Oil that was seeking to construct pipelines through Oklahoma. Haskell’s links to Standard Oil attracted attacks in particular from the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. An increasing liability to Bryan’s campaign, Haskell succumbed to pressure to depart from his party post in late September 1908. This was a stumble from which Bryan’s campaign could not recover.

Even in Bryan’s electoral defeat that November, the deposit guaranty idea continued to resonate among friendly electorates in the southern Plains states. Kansas and Nebraska both passed guaranty laws by March 1909, with Texas following in May. Of the four plans, Oklahoma’s and Nebraska’s were the most generous in the sense that their coverage was obligatory and most comprehensive as to deposit type; moreover, payments to depositors were to be made upfront, out of the guaranty fund, which would be reimbursed through liquidations of failed banks’ assets and additional assessments, if necessary. The Texas plan was less generous in that it restricted the guaranty to non-interest bearing deposits. Finally, the Kansas plan was the least generous—for being voluntary, for restricting deposit type, and for compensating depositors only after liquidation.

Selling Solidity: Deposit Guaranty on Bank Checks

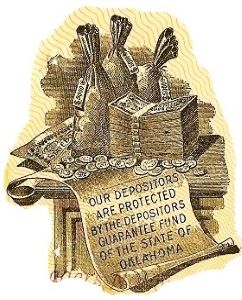

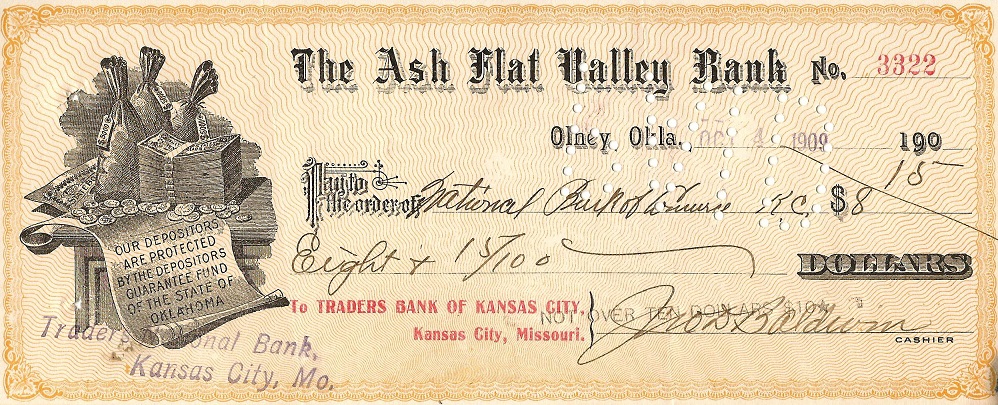

Deposit guaranty plans were meant to be a boon to state banks in their competition with national banks, and the former institutions were not shy about advertising this protection on the drafts and checks which their customers used. In Oklahoma, the pioneer of deposit guaranty, state banks regularly highlighted this protection on their fiscal documents. Whether using simple text, unadorned shields, or more elaborate vignettes, banks sought to signal to their customers the security afforded by their state’s program. One distinctive vignette, used by the Ash Flat Valley Bank of Olney, Oklahoma depicted deposit guaranty as a bountiful pile of currency bundles, sacks of specie, and an abundance of stray loose coins, all sitting atop a government bond whose title peeks out on the left. From underneath all this plenty unravels to the right a scroll proclaiming “Our depositors are protected by the depositors guarantee fund of Oklahoma.”

Ash Flat Valley Bank, Olney Oklahoma, 1909. The same vignette was also used by banks in the towns of Stilwell and Red Oak, among others. (Image source: author's collection)

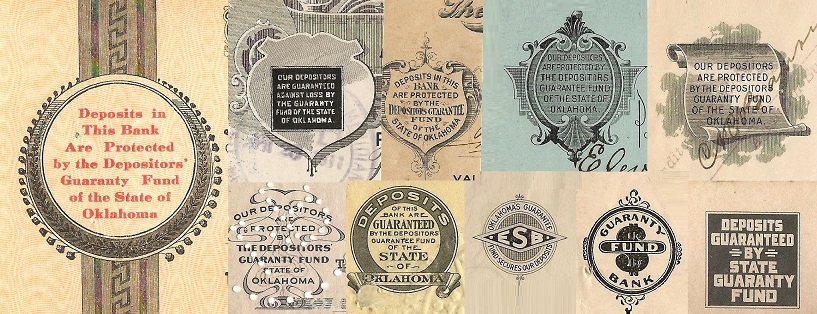

More commonly, state banks used a variety of smaller devices on the checks to proclaim deposit protection, typically a shield or some other sort of logo located at the top left corner of the document. Similar devices were employed by banks in other states with guaranty laws.While the Ash Flat Valley Bank’s wording accurately reflected the terms of Oklahoma’s guaranty law, not all of the state’s institutions were as scrupulous. Though a creature of state law, the guaranty fund was neither financed by the state, nor were any debts it might incur an obligation of the state. If bank failures on a sufficient scale were to empty the fund, only subsequent assessments upon the states’ banks could replenish it, a weakness that nearly crippled the scheme after 1909.

Advertising deposit guaranty on Oklahoma checks. Far left: Olney (1910). Top left to right: Meridian (1911), Shattuck (1912), Oklahoma City (1908), and Idabel (1908). Bottom left to right: Hooker (1916), Keota (1918), Kieffer (1920), Haworth (1911), Sasakwa (1922). (Image source: author's collection)

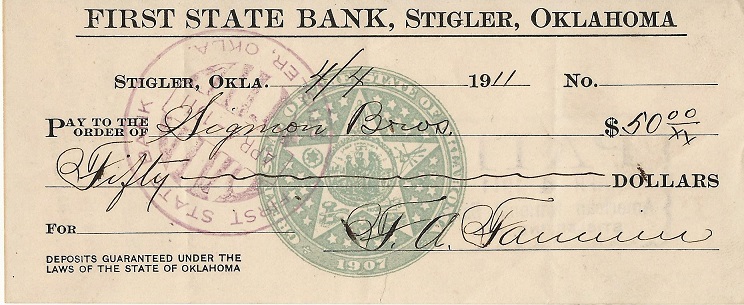

Oklahoma banks were admonished by state authorities if they advertised, incorrectly, that deposits were guaranteed by the state of Oklahoma and not merely by the guaranty fund. Some were vaguer in the wording of their promises than others. One particularly bold institution, the First State Bank of Stigler, not only went with misleading text but saw fit to emblazon its checks with the state seal of Oklahoma, as if the check were somehow a liability of the state itself!

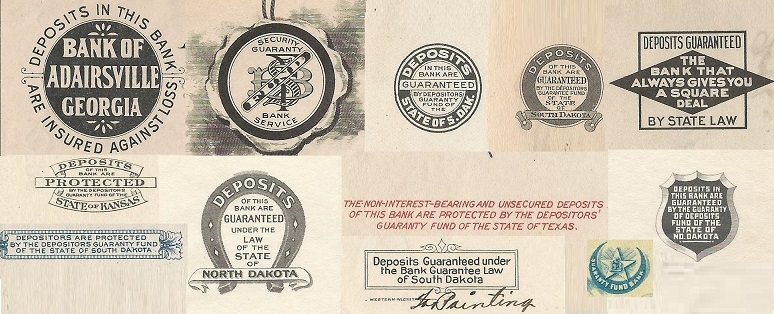

Deposit guaranty depicted in other states. Top left to right: Adairsville, GA (1923); Lorenzo, TX (1923); Blunt, SD (1922); Blunt, SD (1923); Winner, SD (1917). Bottom left to right: Dodge City, KS (1920); Redfield, SD (1920); Hanks, ND (1922); Quanah, TX (1920); Valley Springs, SD (1924); Bowie, TX (1921); Rugby, ND (1923). (Image source: author's collection)

Dimming of the Oklahoma Precedent

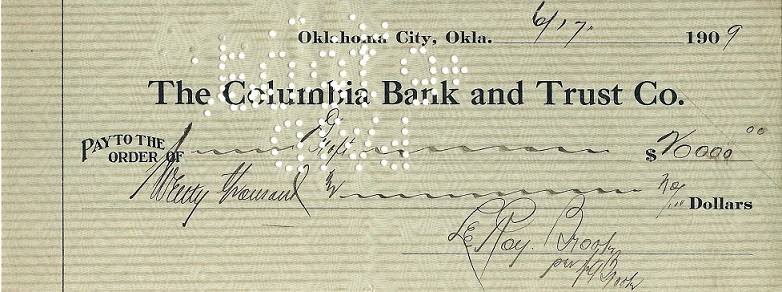

After the contrived success of the Coalgate liquidation in late 1908, the Oklahoma guaranty plan experienced a far more ominous challenge with the failure of the Columbia Bank and Trust Company of Oklahoma City on September 28, 1909, its portfolio stuffed with bad oil paper. Obliged to pay off depositors immediately, the Oklahoma’s deposit guaranty plan was crippled, and failures of the Planter’s and Mechanic’s bank and the Night and Bay bank in 1911 only added to this burden. A delegation of Wisconsin bankers, arriving in September 1909 to study the Oklahoma guaranty plan in the midst of the Columbia turmoil, returned home to advise state officials against following Oklahoma’s example.

Overselling solidity in Stigler, Oklahoma, 1911. (Source: author's collection)

Changes to Oklahoma’s guaranty law in 1909 and 1913 made it less generous to depositors, but increased assessments on member banks prompted those who could to convert from state to national charters, leaving a pool of smaller and weaker banks to soldier on. Oklahoma’s deposit guaranty plan managed to return to the black by 1920, only to be crushed by the sharp depression of 1920-1921, leading to the plan’s repeal by March 1923. The resulting collapse in agricultural prices stressed the other three plans as well, leading to their eventual demise and repeal in Texas (1925), Kansas (1929), and Nebraska (1930).

A check paid on the Columbia Bank and Trust Co., June 1909. The Columbia's insolvency that September nearly wrecked Oklahoma's deposit guaranty plan. (Image source: author's collection)

The Late Movers: Mississippi, the Dakotas, and Washington

Despite the bad odor left by Oklahoma’s experience, a second clutch of state deposit guaranty laws did pass between 1914 and 1917 in Mississippi, South Dakota, North Dakota, and Washington. Mississippi’s plan was part of the progressive agenda of Governor Earl Brewer. Progressive forces secured in South Dakota secured a law in 1916, with North Dakota following the year later out of fear of losing deposits to its neighbor. Washington’s plan was the most anomalous, given its geographic distance from the other guaranty states, and the fact that it alone of the eight states allowed branch banking. Failures among some Seattle banks seem to have provided the impetus for the adoption of a guaranty law in that state. Despite being the last plan to be established, it was the first of the eight to fail (1921). South Dakota’s ended in 1927, North Dakota in 1929. Mississippi’s plan lasted until 1934, but had been insolvent for some years already.

In all eight guaranty states, the plans succumbed to a mix of common factors. Oklahoma’s plan, politicized by the 1908 presidential contest, was both underfunded and overly generous with its benefits, which encouraged a surge in the number of small, undercapitalized state banks. While this worsened the risk profile of the fund, the first and biggest blows were inflicted not by small banks but by large ones that took advantage of lax regulation. Such moral hazard effects were evident in other states. But despite their flaws, all these policy experiments were eventually wrecked by external shocks, whether it was the 1920s collapse in farm prices or the advent of the Great Depression itself.

Conclusion

Charles Nathaniel Haskell and William Jennings Bryan were both ambitious politicians who seized upon the Panic of 1907 as a pretext for promoting an innovation that also served their electoral aspirations. In the 1908 campaign, Bryan intended that the Oklahoma experiment would become a compelling template for a national deposit guaranty. After The Great Commoner’s loss, the drawbacks of Oklahoma’s version of deposit guaranty soon became manifest. With minimal barriers to entry, the growth in state banks and their deposits was dramatic. This growth also swelled the guaranty fund, as new banks contributed their initial capital assessments and as larger deposits generated larger assessments. Yet as the blow of the Columbia failure fell, the requirement that depositors be paid immediately seriously embarrassed the plan. Thereafter Oklahoma’s plan was no longer touted as a model for state or national deposit guaranty, and later state plans were established on a more conservative basis.

..........

REFERENCES

Daily Oklahoman, August 1, 1908.

Golembe, Carter H. 1960. “The Deposit Insurance Legislation of 1933: An Examination of its Antecedents and its Purposes” Political Science Quarterly 75(2), pp. 181-200.

Kansas. 1908. Senate Journal. Proceedings of the Senate of the State of Kansas, Special Session, January 16 to February 4, 1908. p. 28.

Hightower, Michael J. 2013. Banking in Oklahoma Before Statehood (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press).

Oklahoma. Various dates. Annual and Biennial Reports of the State Banking Commissioner.

Robb, Thomas Bruce. 1921. The Guaranty of Bank Deposits (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co.).