Bringing Vignettes to Life

When Jenny Lind Circulated in America

Introduction

IN HER STUDY of women on currency, Virginia Hewitt observes that “almost all women on notes are personifications or idealizations, even when they appear in realistic form.” As the use of paper money became widespread in the 19th century, advances in engraving technologies enabled banknote printers to resort to finely-wrought human portraits as a measure to thwart counterfeiting. Drawing on all manner of wash drawings, lithographs, and later photographs, banknote engravers in the mid-19th century created stocks of portrait images, known as “fancy heads”, that their clients could choose from to adorn their currency. Key to the usefulness of those portraits was their widespread recognition by the banknote-using public, who might have the perceptive capacity to distinguish between well-executed renderings of famous portraits on genuine notes and badly-done portraits on counterfeits. Given that men dominated public life, historical figures portrayed on American banknotes were, almost without exception, male. Women appeared on currency for the most part either in stylized and anonymous depictions of daily work life or as personifications of some ideal or virtue, typically garbed in robes evocative of classical antiquity.

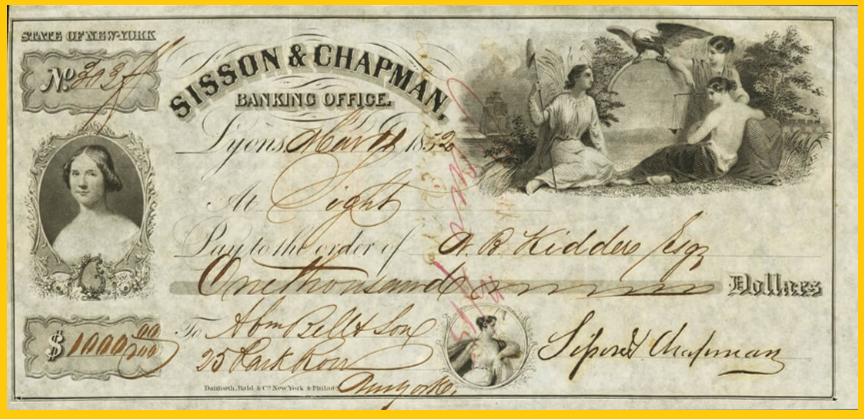

A sight draft from 1852, printed by Danforth, Bald & Co., on the private bank of Sisson & Chapman of Lyons, New York (Image Source: Heritage Auctions).

One singular exception to this pattern can be found on this sight draft issued on the firm of Sisson & Chapman, a small private bank that operated between 1850 and 1856 in the town of Lyons in the western part of New York State. If the top right of the draft features a characteristic arrangement of allegorical figures looking away in languid self-absorption, the portrait to the left makes an entirely different impression. Wearing a simpler, period hair style and plain dress, the young woman directly meets the gaze of her onlookers with her own forthright yet demure regard. Lacking exotic raiment or any particular beauty, her countenance is prim rather than glamorous, her overall appearance bourgeois rather than aristocratic.

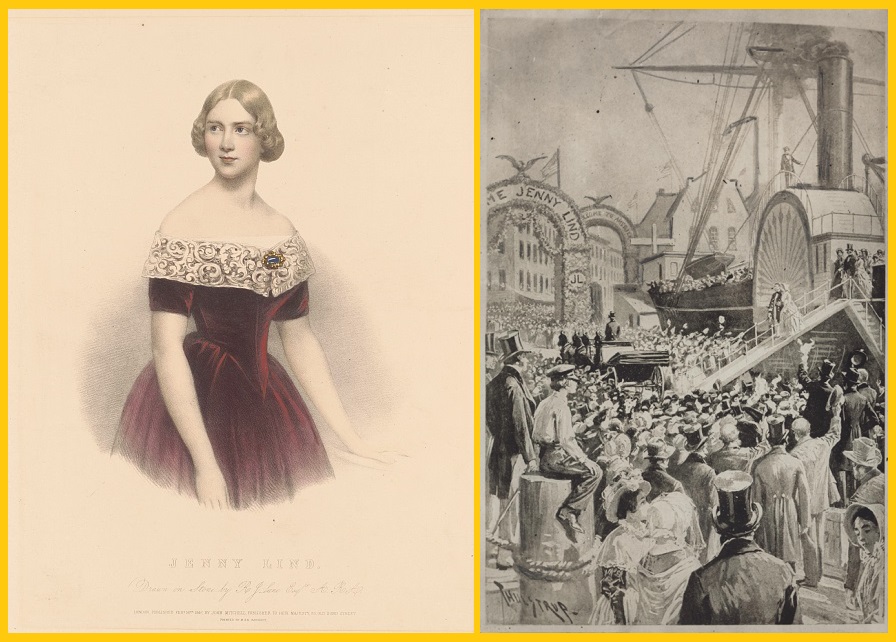

Left image: Check portrait, enlarged. Right image: cropped portrait by an unknown American artist of the 1850s (Image source: reproduced in Ware and Lockard 1980). While there were abundant examples of Jenny Lind's likeness for any engraver to work from, this portrait seems to bear a particular similarity in the roundness of the cheeks.

Anyone receiving this bank draft, and probably a large swathe of the American public by the early 1850s, would have immediately recognized this portrait as that of Jenny Lind, the famous opera singer known as the “Swedish Nightingale.” Embarking in late 1850 on a performance tour of the United States under the management of the impresario Phineas T. Barnum, Lind’s presence in the country for nearly the next two years unleashed a storm of adulation, referred to at the time as “Lindomania”, that represented an early example of how a mass popular culture, even one grounded on an egalitarian ethos like the United States, could nonetheless generate extreme forms of celebrity worship.

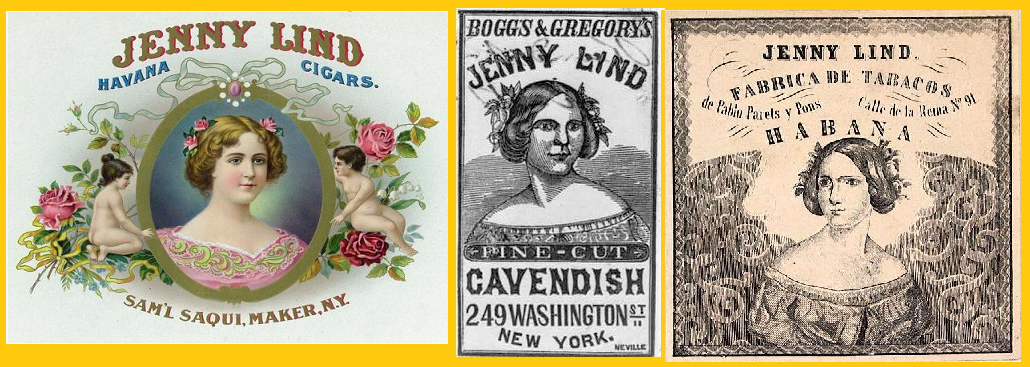

During the Swedish singer’s American tour, Lindomania manifested itself among other ways in a flood of everyday material artefacts identified with Jenny Lind—mementos, commemoratives, consumer items, and bric-a-brac of all sorts—all by which their producers sought to celebrate or otherwise profit on the diva’s presence. Invariably, much of this cultural flotsam was either crass or even humorously inappropriate (Jenny Lind chewing tobacco, Jenny Lind cigars—the smell of which she detested). Lind also appeared on a range of banknotes and other fiscal paper. In addition to the Sisson & Chapman draft pictured above, Lind’s portrait was also featured, by one count, on currency issued by eighteen different banks across ten states and the District of Columbia. Not just an historical female but a living person, Jenny Lind’s presence on American money at that time represented a distinctive departure from the prevailing, male-dominated conventions of banknote portraiture.

Jenny Lind Travels to the United States

Born in 1820 in Stockholm, Sweden, out of wedlock and to a divorced mother, Johanna Maria (“Jenny”) Lind began life in inauspicious circumstances. Fortunately her musical precocity was recognized early and nurtured. From her grandmother, Jenny acquired the outlook and habits of religious devotion that became a prominent aspect of her public persona. After training at the Royal Theatre of Stockholm, Lind’s talents were honed by the best teachers of Europe. By the age of 21 she had performed hundreds of times on the Royal Theatre stage and the enormity of her vocal talents was confirmed by such contemporary authorities as Chopin, Mendelssohn, and Clara Schumann. Her touring career in Europe also took her to Great Britain, where between 1847 and 1848 her performances created a public sensation that prefigured what later happened in the United States.

On the surface, the partnership between Jenny Lind and Phineas T. Barnum seemed incongruous. Lind, an international star and the reputational embodiment of Victorian piety and female virtue, had joined forces with the roguish Yankee showman and self-anointed “Prince of Humbug.” Gaining notoriety for developing his American Theatre in New York City into a showcase of hoaxes and freak shows, P.T. Barnum had his own international experience with the marketing and exhibition of the dwarf General Tom Thumb (Charles Sherwood Stratton) to European audiences between 1844 and 1847. After Lind completed her own British tour, Barnum reached out in 1849 to engage Lind, sight unseen and voice unheard, for a schedule of appearances in the United States at the astounding rate of $1,000 a performance for a maximum run of 150 engagements. In addition to handling the promotion and logistics of Lind’s visit, Barnum also promised to bankroll the travelling expenses of Lind and her entourage and provide for any charity concerts that the Swedish Nightingale chose to give. Finally, as a guarantee to Lind Barnum committed to depositing the entire financial commitment of $187,500 upfront in a London bank.

The extravagance of this arrangement represented a huge financial risk for Barnum, who had to mortgage most of his assets to make that payment. Not only had Barnum himself never actually heard Jenny Lind sing, but most Americans had no idea who she was! Barnum, a cultural philistine who prospered by pandering to the mass tastes of his audiences, had no particular insight into the quality of Lind’s talents. However, what he did grasp better than most was the cultural dynamics of celebrity, which was hardly peculiar to American society. After all, the same British royal family that fêted Jenny Lind in 1847 had also been charmed by the antics of General Tom Thumb in 1844.

While American audiences might not have a sophisticated appreciation for opera, their capacity for celebrity adulation could drive ticket sales if Jenny Lind’s image could be suitably crafted and marketed. As Barnum explained a few years later in his Autobiography, “although I relied prominently upon Jenny Lind’s reputation as a great musical artiste, I also took largely into my estimate of her success with all classes of the American public, her character for extraordinary benevolence and generosity … as I felt sure that there were multitudes of individuals in America who would be prompted to attend her concerts by this feeling alone.” Barnum’s genius lay in his recognition that if Lind’s reputation for modesty, piety, and charity could be entrenched in the popular mind, audiences would then experience and appreciate her vocal performances as external expressions of these inner traits.

Left: A particularly fetching lithograph of Lind by Richard James Lane, 1847. Right: Depiction of Lind's arrival in New York City. (Image Sources: Library of Congress; Ware and Lockard 1980).

For her part, Jenny Lind was hardly the exploited ingenue in her partnership with the “Prince of Humbug.” At the height of her vocal powers, the diva had announced in 1849 her retirement from the European stage, desiring a shift in her musical career away from the grind of operatic repertory to a more leisurely schedule of concert hall performances. Moreover, she had definite plans to set up a system of free music schools in Stockholm, a charity project that would require considerable funds that she could earn on an American tour. Towards this end, not only did Lind drive a hard initial bargain with Barnum, she insisted later on renegotiating the agreement to her greater benefit when she realized how much money her American concerts promised to make. Americans from Barnum on downward cashed in on Jenny Lind; at the same time, Lind also cashed in on herself.

In Barnum’s capable hands, the artifice of marketing Jenny Lind’s sincerity was both a resounding success and, at times, unavoidably grotesque. Thanks to Barnum’s advance publicity and his influence with the newspapers, some thirty thousand New Yorkers showed up at the harbor to greet Lind’s boat when she first arrived from England on September 1st, 1850. For her initial concert, Barnum arranged for an auction of the first ticket in a way that would guarantee valuable publicity to the highest bidder. The winner of that first auction, John Genin, was a hatter and (not coincidently) a Broadway neighbor to Barnum’s American Museum. Genin’s outrageous bid of $225 for a single ticket, paired with Lind’s announcement that she would donate the entire proceeds of her first New York performance to various charities, had an electric effect upon the American public.

Pairing acts of conspicuous consumption and conspicuous generosity in that way triggered a paroxysm of mass veneration that assured Lind enthusiastic audiences wherever she performed. Like some vast performance of the anthropologist’s potlatch, the American public splurged on Jenny because she splurged on them. Barnum applied the same formula in city after city: the advance priming of a sycophantic press, much of which was on Barnum’s payroll; the mobilizing of crowds; the elaborate welcoming ceremonies that celebrated Mlle. Lind and the Christian virtues which she personified; the auctioning of tickets for extravagant effect (and at prices far higher than what even John Genin had paid); and finally Lind’s own reciprocal acts of charitable noblesse oblige, large and small, which she regularly indulged in with obvious awareness of their reputational benefit. Even those moments when Lind pushed back against the attention and appealed for her privacy themselves became occasions for further public admiration of her modesty and humility.

Then there was the Swedish Nightingale’s music itself. A typical performance involved selections from Lind’s past operatic roles, along with a selection of what were basically folk songs, the Herdsman’s (“Echo”) Song being an audience favorite. In addition, among the more prominent members of her traveling entourage, Lind was accompanied by two accomplished musicians, the baritone Giovanni Belletti and the pianist and conductor Julius Benedict. After opening in New York, Lind’s concert schedule took her Boston and the New England states before a swing southward that reached Charleston, South Carolina, by New Year’s Eve of 1851. At this point, Lind and her entourage embarked upon a somewhat perilous voyage to Havana, Cuba. Returning to America via New Orleans, Lind’s performance schedule took her up the Mississippi and Ohio rivers as far as Pittsburgh, which was the site of one ill-starred concert marred by drunken rioters, whose destructive behavior resulted in the cancellation of her remaining dates in that city. By May 1851, the performance tour returned to the East Coast.

Aside from the Pittsburgh debacle and tough crowds in Havana, Jenny Lind’s reception in America, both with respect to her celebrity status and the quality of her vocal performances, was rapturous, confirming Barnum’s conjecture about the collective psyche of his countrymen. Yet the intensity of this enthusiasm did have its dark moments. For example, at a public appearance in Baltimore Lind accidently dropped her shawl, which was then seized upon and torn into little pieces by frenzied souvenir hunters. By telegraphing ahead the precise date and time of her arrival in each city, Barnum’s publicity machine made such unsettling encounters more likely.

True to her philanthropic reputation, Lind regularly held charity concerts in addition to those for Barnum, donating the proceeds to various charities in whatever locales she was performing. The enthusiasm for the previously unknown opera singer, deemed variously “Lind mania” or “Lindomania”, manifested itself particularly in a flood of commercial products and other souvenirs that sought to capitalize on the diva’s celebrity. Ranging from pictures, songbooks, and commemorative knick-knacks to consumer goods that bore no discernable relation to singing and music (let alone to Jenny Lind), entrepreneurs cashed in on the Swedish Nightingale’s public image. Although distressed by the commercial excess, not only was Lind powerless to prevent the exploitation of her name and likeness but Barnum himself welcomed it as part of the swell of publicity that would sell tickets. Inevitably, some of this output tended to be vulgar and over the top. While European commentators snobbishly poked fun at these American excesses, in truth there had already appeared a good deal of “Lindomania” on the other side of the Atlantic as well. Even some Americans grew weary of the onslaught. As one newspaper summarized the obsession by September 1851, “we had yesterday the pleasure of being shaved with a Jenny Lind razor by a Jenny Lind barber, scented with Jenny Lind cologne, combed with a Jenny Lind comb, brushed with a Jenny Lind brush, washed in a Jenny Lind bowl, and wiped with a Jenny Lind towel. After which we put on a Jenny Lind hat, walked into Jenny Lind restaurant and partook of Jenny Lind sausages. Then we took up a Jenny Lind paper, read a Jenny Lind editorial, smoking a Jenny Lind cigar; throwing ourselves back in a Jenny Lind revery.”

Jenny Lind's image was used to sell a variety of tobacco products which a woman of her station could not use, and whose smell she could not abide. (Image Sources: Library of Congress; eBay).

Upon reaching the east coast in May of 1851, two events altered the course of her American tour and indeed her life. The first was Julius Benedict’s resignation from the entourage to take a conducting position in London. Needing a pianist to replace him, Lind wrote to Germany to engage the services of a younger colleague, Otto Goldschmidt. Upon Otto’s arrival, the two kindled a romantic relationship that resulted, by February 1852, in their marriage in Boston. The second event was Lind’s termination of her arrangement with Barnum in June of 1851. Her agreement with Barnum had given her the option of ending the arrangement after one hundred concerts. Wearied of Barnum’s flamboyant, publicity-driven style, Lind also arranged to buy out Barnum’s share for the few remaining concerts under her contract (she performed ninety-three under Barnum’s management). Henceforth Lind and her entourage continued touring the country on their own in a more subdued fashion, in particular eschewing Barnum’s predilection for auctioning tickets at eye-watering prices. Without the auctions, ticket scalpers simply stepped in to exploit the public, which Lind was powerless to prevent. With Otto Goldschmidt as her pianist, Lind performed fifty-seven more concerts. After their marriage, the couple enjoyed a relatively peaceful and carefree three-month honeymoon in Northampton, Massachusetts before concluding the tour with a round of farewell performances in the major eastern cities.

Despite the differences in temperament that led to the end of their collaboration, Barnum’s and Lind’s relations were fundamentally amicable. Both profited handsomely from their partnership. After settling with Lind for her early contract termination, Barnum’s share of revenue from the tour amounted to over $500,000; net of expenses (including financing Lind’s entourage), his profit was some $200,000. Lind’s share of the proceeds under her revised contract was nearly $180,000, excluding the philanthropic contributions she regularly made from her charity concerts (how much she later made touring without Barnum is unknown). These were enormous sums in 1850s money. Barnum’s assessment of the potential in bringing Jenny Lind to America proved more than justified. Not only were the amounts that Barnum had promised to pay Lind astonishing, widespread public knowledge of these extravagant contract terms was itself crucial for Barnum’s promotional efforts. Likewise, the fact that Lind was motivated by her desire to endow free schools in Scandinavia was also generally known and contributed to her reputation for charity and benevolence. Contemporary newspaper reporting and commentary on Jenny Lind’s performances, copiously excerpted by Porter Ware and Thaddeus Lockard in their history of her American tour, make it abundantly clear that American audiences perceived Lind’s vocal talents as direct expressions of her Christian ideals and of her Victorian feminine virtues. To that extent, Barnum’s intuition about what it would take to loosen Americans’ wallets was spot on.

The Sisson & Chapman Bank Draft

Although the Sisson & Chapman bank draft pictured above is itself a rather common piece of financial ephemera, it seems to be the only instrument of that sort to have ever featured Lind’s portrait. The two principals of that bank, William Sisson (1787-1863) and Daniel Chapman (1799-1861) were in the banking business together only from 1850 to 1856 when Sisson retired, after which Chapman continued banking under his own name until 1860. Both men were prominent citizens of Lyons, New York. Sisson, born in Connecticut, moved to Lyons in 1816. A lawyer by profession, he served as a justice of the peace and master in chancery until 1830, when he was appointed judge of the Court of Common Pleas (a son, also named William, became a druggist in Lyons and predeceased his father in 1859). Chapman, from Massachusetts, trained as a physician at Harvard University in 1820-21, after which he moved to Lyons and set up his practice there. Despite his medical background, Chapman’s occupation is given in the 1860 census as “banker.” Whether either man had a particular enthusiasm for Jenny Lind, or simply ordered that particular “fancy head” for their checks from the stock of portraits offered by Danforth, Bald & Co., cannot be known. The closest that Jenny Lind came to Lyons was in July 1851, when during the post-Barnum phase of her tour she sang in both Rochester and Buffalo. It was not impossible that either man, with their personal financial means, might have ventured to attend one of Lind’s concerts.

Jenny Lind on Antebellum Banknotes

A slight variant on the portrait of Jenny Lend that appeared on the Sisson & Chapman draft was also used on currency issued by at least eighteen banks starting in the early 1850s. All of these notes were printed either by Danforth, Bald & Co. (1850-1852), Danforth, Wright & Co. (1853-1858), or the American Bank Note Company (after 1858), for a range of client banks from New England to the western states of Illinois and Indiana.

Banks that Issued Currency Using Jenny Lind’s Portrait:

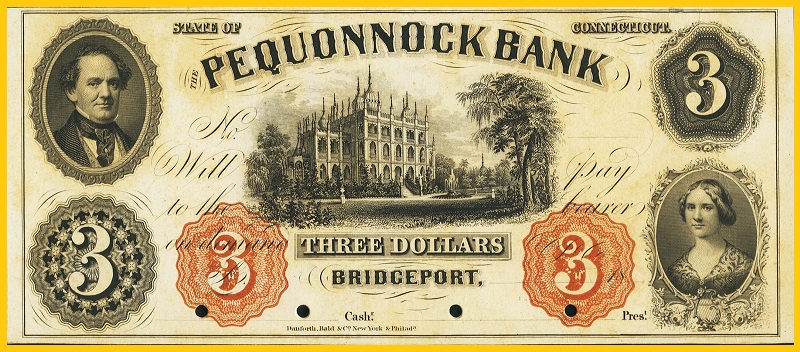

CT-Bridgeport- The Pequonnock Bank (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

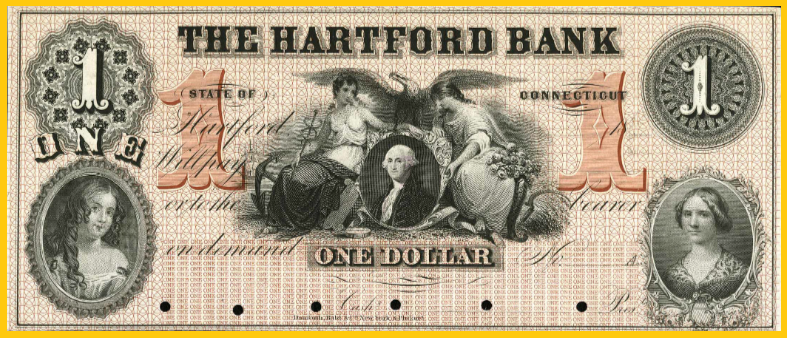

CT-Hartford- The Hartford Bank (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

CT-Southport-The Southport Bank (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

GA-Savannah- The Bank of Savannah, (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

IL-Chicago- The Merchants and Mechanics Bank (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

IL-Danville-The Stock Security Bank (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

IL-Springfield- The Bank of Lucas & Simonds (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

IN-Newport-The Bank of North America (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

IN-Plymouth- The Western Bank, (Danforth, Wright & Co.)

ME-Waldoboro- The Medomak Bank (Danforth, Wright & Co.)

MA-Springfield-The Springfield Bank (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

NJ-Cape May County-The Bank of America (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

NJ-Flemington- The Tradesmens Bank (listed by Hessler, but unconfirmed by Heritage)

NJ-Newark-The Mechanics Bank at Newark (Danforth, Bald & Co.; American Bank Note Co.)

PA-Easton-The Farmers and Mechanics Bank of Easton (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

RI-Alton-The Richmond Bank (Danforth, Wright & Co.)

Wash. DC.-The Arlington Bank (Danforth, Wright & Co.)

Wash. DC- The City Bank (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

Wash, DC- Potomac Savings Bank (Danforth, Bald & Co.)

Sources: Hessler (1999); Heritage Auctions archives.

A $1 note on the Hartford (Connecticut) Bank featuring George Washington, an anonymous female, and Jenny Lind (Image Source: Heritage Auctions).

Given her public acclaim and how widely recognized her face became, using Jenny Lind’s image on a banknote was understandable from a security point of view, even if the resulting compositions were stylistically a bit random. Depending upon the bank, Lind’s “fancy face” was mixed with other, anonymous, female portraits; with the usual allegorical scenes; and with the portraits of historical men like Presidents George Washington and Millard Fillmore (the last combination, on notes issued by The City Bank of Washington D.C., made at least a little sense given that Lind had actually met President Fillmore and his musical family when she performed in that city in December 1850). The most notorious appearance of Jenny Lind on a banknote came with an issue from The Pequonnock Bank of Bridgeport, Connecticut, of which Barnum himself was President. Barnum, at the top left, is balanced by Lind on the bottom right, with a vignette of Barnum’s ostentatious Bridgeport mansion, “Iranistan” in the center. For some, this bit of monetary self-aggrandizement went too far, even for a person as solicitous of the Almighty Dollar as Barnum. As the Boston Morning Journal wrote in December 1851:

BARNUM THE BANKER. We have been shown some of the notes of Barnum’s Pequonnock Bank (Connecticut) which are very handsomely engraved, with portraits of Barnum and Jenny Lind, looking as lovingly at each other as a pair of turtle doves. In the center of the bill we are treated to a fine engraving of the palace of Iranistan, or Barnum Castle, at Bridgeport. This is certainly a very pretty mode of advertising; and as the great showman is a candidate for Governor in the land of wooden nutmegs, we have no doubt but his handsome portrait will be largely circulated in the canvass. There is but one Barnum, and Jenny is his profit (quoted in Ware and Lockard, p. 117).

A $3 note on the Pequonnock Bank of Bridgeport, Connecticut. This bank took on a national charter (no. 928) in 1865 to become the Pequonnock National Bank of Bridgeport. (Image source: Heritage Auctions).

Despite the quote’s political reference, Barnum was never elected Governor of Connecticut, although he did serve some years in the state legislature and, later in life, became Mayor of Bridgeport. Along the way he went into the theatre business, toured as a temperance lecturer, managed to go bankrupt, and yet re-emerged as the circus promoter for which most people remember him. A vivid example of that American character type whose existence consists of their constant self-reinvention, Barnum’s exploits elicited both admiration and disgust and often for the same reasons.

In the arc of his life, Barnum’s partnership with Jenny Lind became just one of the more lucrative episodes of his long career in the public eye. For her part, the Swedish Nightingale left America for good in May 1852, not only with the wealth she had aimed to acquire but a husband as well. After a few years in Germany, Jenny Lind-Goldschmidt and her family moved to England. Her music schools in Sweden endowed, Lind-Goldschmidt continued giving concerts but remained retired from opera, otherwise occupying herself professionally with musical education and instruction.

After the merger of its antecedent firms into the American Bank Note Company in 1858, Jenny Lind’s portrait soon disappeared from American money during those few remaining years before the post-Civil War standardization of the country's currency occurred. As Virginia Hewitt notes, the appearance of historical women as banknote portraiture became widespread only by the late 20th century, although certainly by no means in the United States. Lind and her musical achievements were finally commemorated by her native country on a 50 kronor note first issued in 1996, with her image engraved after a mid-19th century illustration by the Austrian Fritz L’Allemand. Ironically, this numismatic honor has rapidly lost its meaning as Sweden becomes a cashless society, a trend promoted by another musician, Björn Ulvaeus of ABBA fame who, rather like Barnum, now operates a museum to promote his own legacy.

Jenny Lind on a Swedish 50 kronor note (Image Source: Heritage Auctions).

....................

REFERENCES

Barnum, Phineas Taylor, The Autobiography of P. T. Barnum (London: Ward and Lock 1855), ch. XI, quote p. 118.

Cowles, George W. Landmarks of Wayne County, New York (Syracuse, NY: D. Mason and Co. 1895), p. 106.

Hessler, Gene, “Some Women Who Made a Difference, Part III” Paper Money (July-August 1999), pp. 108-114.

Hewitt, Virginia, Beauty and the Banknote: Images of Women on Paper Money (London: British Museum Press 1994), p. 8 (quote); pp. 54-55.

Kemp, Charles, “Jenny Lind Captures America” The Check Collector No. 79 (July-September 2006), pp. 18-19.

Lynch, Kevin Hugh, “The Matchless Jenny Lind: A Woman for All Times” The Ephemera Journal 22 (January 2020), pp. 1-8.

The Minnesota Pioneer (St. Paul, Minnesota Terr.), September 11, 1851 (quote about Jenny Lind sausages, etc.). This passage was reprinted in a number of newspapers around this time.

Parker, Sylvia, “Jenny Lind and P.T. Barnum” College Music Symposium 59 (Fall 2019), pp. 1-32.

Saxon, A. H. “P.T. Barnum and ‘The Art of Money-Getting’” Friends of Financial History 50 (Winter 1993-1994), pp. 12-18.

Tomasko, Mark D., Images of Value: The Artwork Behind U.S. Security Engraving 1830s-1980s (New York: The Grolier Club 2017), esp. pp. 43-88.

Ware, W. Porter and Thaddeus C. Lockard, Jr. P.T. Barnum Presents Jenny Lind: The American Tour of the Swedish Nightingale (Louisiana State University Press 1980).

Welsh, Edgar L., “Grip’s” Historical Souvenir of Lyons, N.Y. (Lyons, NY: The Lyons Republican Press), pp. 94-95.