Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

The Forced Issue Notes of the Bank of Louisiana . . . . . . . . . 243

By Steve Feller

Notes from North of the Border: Completion Approaching . . 256

By Harold Don Allen

Tax Anticipation Scrip during the Great Depression . . . . . . . 259

By Loren Gatch

The Paper Column: Spelling Created Trouble with Nationals . . . . . .268

By Peter Huntoon & Bob Liddell

Mrs. Emma Reed, National Bank President . . . . . . . . . . . . 277

By Karl Sanford Kabelac

About Nationals Mostly: The FNB of Farmersville, TX . . . . . . 278

By Frank Clark

Edgar Allan Poe Signed Checks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 280

By Michael Reynard

Mrs. S.R. Coggin, National Bank President . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 283

By Karl Sanford Kabelac

A Theoretical Model of Mormon Currency of Kirtland, OH . . . 285

By Douglas A. Nyholm

The Buck Starts Here: The First Greenbacks . . . . . . . . . . . . 297

By Gene Hessler

Small Notes: New Ones on Letter-Seal 1928 FRN Plates . . . 293

By Jamie Yakes

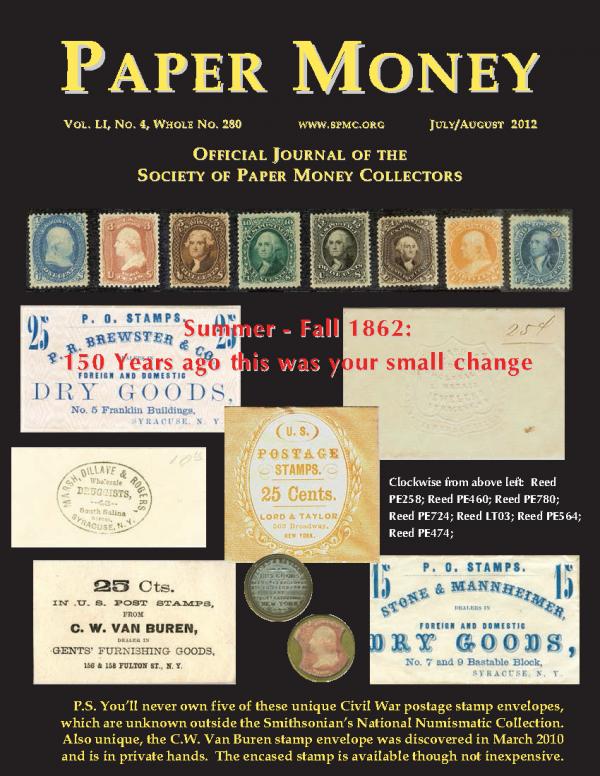

Civil War Stamp Envelopes Circulated as Small Change . . . 298

By Fred L. Reed

A checklist of Civil War Postage Stamp Envelopes . . . . . . . . 306

By Fred L. Reed

SOCIETY & HOBBY NEWS

Information and Officers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .242

Your Subscription to Paper Money Has Expired If . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 246

New Members . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .273

President’s Column by Mark Anderson . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .292

Back of the Back Page with Loren Gatch and Fred Reed . . . . . . . . . . . . . .317

The Back Page with Paul Herbert and John Davenport . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .318