Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

The Paper Column: Series of 1929 Overprints.............................. 3

By Peter Huntoon & James Simek

Collector Wants to Know about KS Lottery Ticket....................... 33

By Rick Osterholt

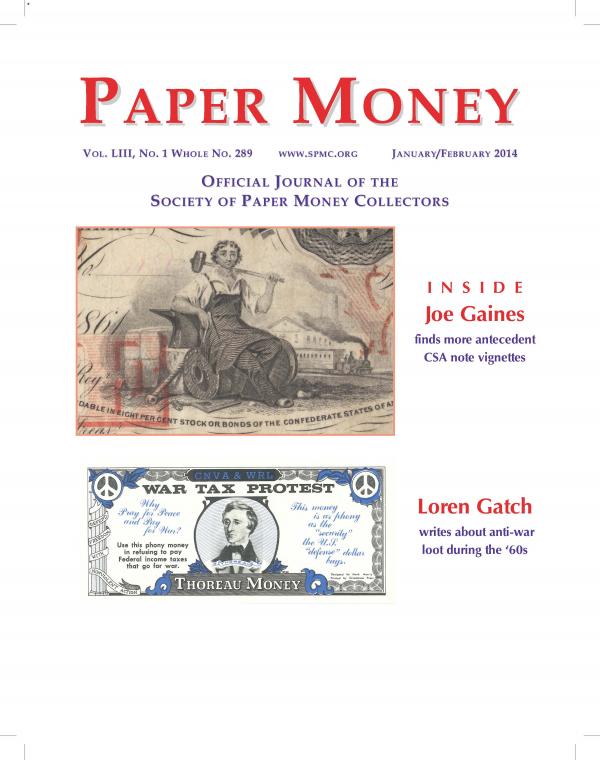

Obsolete Bank Notes with Vignettes Used on CSA T-23 & 32 . . 34

By Joseph J. Gaines, Jr.

The Paper Column: Kearny, NJ National Banks Yield Tales . . .45

By Peter Huntoon & Robert Hearn

Nebraska Territory 1857 City of Omaha Notes........................... 51

By Marv Wurzer

The Buck Starts Here: Card Shows Unused Design......................... 62

By Gene Hessler

Small Notes: Late-Finished $5 Face Plate 147................................ 64

By Jamie Yakes

‘Thoreau Money’ and War Tax Resistance.................................. 66

By Loren Gatch

Lofthus Paper Money Story Kicks Off Frenzy.............................. 50

New Members.............................................................................. 33

Help the Society Reconnect with These Life Members............... 44

President’s Column by Pierre Fricke........................................... 56

Uncoupled: Paper Money’s Odd Couple by Boling & Schwan............... 58

Money Mart....................................................................................... 57

Fricke CSA Booklet Offers ‘Elegant, Compact Bargain” review ....................... 74

Second Call: George W. Wait Memorial Prize Announcement.............. 75

Civil War Stamp Envelopes, The Issuers & Their Times review........... 76

Draft of SPMC Revised Book-Publishing Policies................................. 78

The Back Page with Loren Gatch & Fred Reed.......................... 80