Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

The Fabulous High Denomination Feds of 1918--Lee Lofthus.........................................160

Identification of Make-Up Replacement Type Notes--Peter Huntoon & Shawn Hewitt.....178

Dick Gregory's "One Vote" Note--Loren Gatch..................................................................192

First National Bank of West Plains, Missouri--Frank Clark.................................................196

The "English" Series of Notes of the Philippines--Carlson Chambliss................................201

The Famous Polar Bear Vignette--Terry Bryan...................................................................210

Mysterious Series of 1935 $1 Back Plate 2--Jamie Yakes..................................................216

Uncoupled--Joe Boling & Fred Schwan...............................................................................220

Small Notes--Jamie Yakes...................................................................................................224

Obsolete Corner--Robert Gill................................................................................................227

Chump Change--Loren Gatch..............................................................................................230

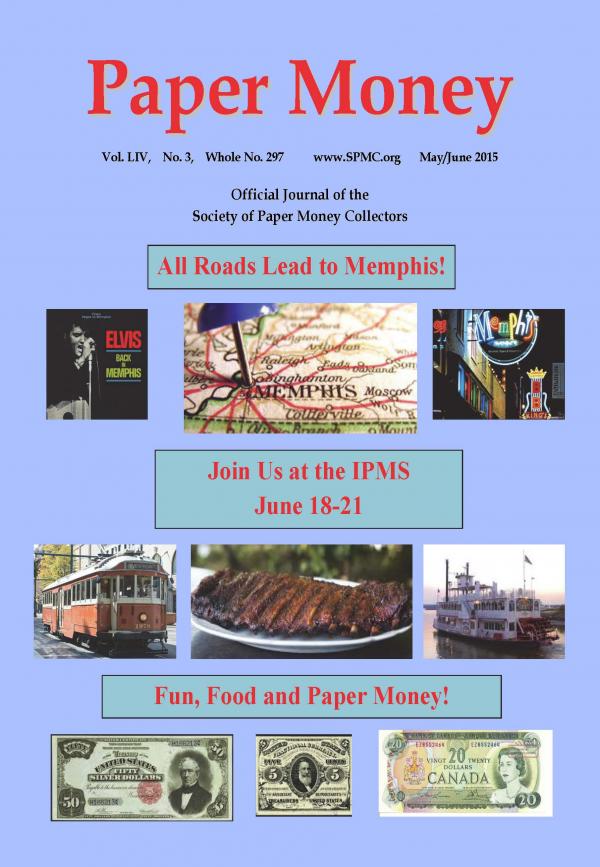

Editor Sez--Benny Bolin........................................................................................................231

President's Column--Pierre Fricke........................................................................................232

SPMC Hall of Fame Class of 2015.......................................................................................233

Membership Report--Frank Clark.........................................................................................234

Selected Bibliography of Colonial/Continental Paper Money--Roger Barnes......................237

Money Mart..........................................................................................................................242