Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

Misspelling Error on $1000 Series 1882 Gold Certificates--Peter Huntoon

Progression to the Misspelling Error--Peter Huntoon.

The Farmers& Merchants National Bank--David Hollander

Zambia – “Chain Breaker”--David B. Lok

Plate Numbers on Series 2000 $10 FRNs--Joe Farrenkopf

A Montgomery Mystery--Bill Gunther

Oak Hill Store--Ronald Horstman

1231 E. Dyer Road, Suite 100, Santa Ana, CA 92705 • 949.253.0916

123 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10019 • 212.582.2580

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • New Hampshire • Hong Kong • Paris

SBG PM Mar2019AucSol 180926

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

Peter A. Treglia

LM #1195608

John M. Pack

LM # 5736

Peter A. Treglia

John M. Pack

Brad Ciociola

Peter A. Treglia Aris MaragoudakisJohn M. Pack Brad CiociolaManning Garrett

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Now Accepting Consignments to the

O cial Auction of the Whitman Spring Expo

Stack’s Bowers Galleries continues to realize strong prices for currency, as shown by these results from our recent

auctions. We are currently accepting consignments to the O cial Auction of the 2019 Whitman Coin & Collectibles

Spring Expo. Headlining our Spring Expo Auction will be Part III of the Joel R. Anderson Collection and Part II

of the Caine Collection. Whether you have an entire cabinet or just a few duplicates, the experts at Stack’s Bowers

Galleries are just a phone call away and ready to assist you in realizing top dollar for your currency.

Auction: February 27-March 2, 2019 | Consign U.S. Currency by: December 31, 2018

Call one of our currency specialists

to discuss opportunities for upcoming

auctions. ey will be happy to assist

you every step of the way.

800.458.4646 West Coast O

ce

800.566.2580 East Coast O

ce

T-2. Confederate Currency.

1861 $500. PMG Very Fine 30.

Realized $39,950

Fr. 2220-F. 1928 $5000 Federal Reserve Note.

Atlanta. PCGS Very Fine 30 PPQ.

Realized $129,250

Deadwood, South Dakota. $10 1882 Brown Back.

Fr. 487. The American NB.

PCGS Very Fine 30 PPQ. Serial Number 1.

Realized $64,625

Fr. 202a. 1861 $50 Interest Bearing Note

PCGS Currency Very Fine 25.

Realized $1,020,000

Fr. 346d. 1800 $1000 Silver Certifi cate of Deposit.

PCGS Currency Very Fine 25.

Realized $1,020,000

Fr. 183c. 1863 $500 Legal Tender Note

PCGS Currency Very Choice New 64 PPQ.

Realized $900,000

Fr. 187b. 18803 $1000 Legal Tender Note

PCGS Currency Choice About New 55.

Realized $960,000

Fr. 2. 1861 $5 Demand Note

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Realized $372,000

Ketchikan, Alaska. Small Size $5. Fr. 1800.

The First NB of Ketchikan. Charter #4983.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ*.

Realized $90,000

Terms and Conditions

PAPER MONEY (USPS 00-3162) is published every

other month beginning in January by the Society of

Paper Money Collectors (SPMC), 711 Signal Mt. Rd

#197, Chattanooga, TN 37405. Periodical postage is

paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal

Mtn. Rd, #197, Chattanooga,TN 37405.

©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2014. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or

part withoutwrittenapproval is prohibited.

Individual copies of this issue of PAPER MONEY are

available from the secretary for $8 postpaid. Send

changes of address, inquiries concerning non - delivery

and requests for additional copies of this issue to the

secretary.

PAPER MONEY

Official Bimonthly Publication of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc.

Vol. LVII, No. 6 Whole No. 318 November/December 2018

ISSN 0031-1162

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the Editor.

Accepted manuscripts will be published as soon as

possible, however publication in a specific issue

cannot be guaranteed. Include an SASE if

acknowledgement is desired. Opinions expressed by

authors do not necessarily reflect those of the SPMC.

Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory

stick/disk to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or

color JPEGs at 300 dpi. Color illustrations may be

changed to grayscale at the discretion of the editor.

Do not send items of value. Manuscripts are

submitted with copyright release of the author to the

Editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

Alladvertising onspaceavailable basis.

Copy/correspondence shouldbesent toeditor.

Alladvertisingis payablein advance.

Allads are acceptedon a “good faith”basis.

Terms are“Until Forbid.”

Adsare Run of Press (ROP) unlessaccepted on

a premium contract basis.

Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be

prepaid according to the schedule below. In

exceptional cases where special artwork, or additional

production is required, the advertiser will be notified and

billed accordingly. Rates are not commissionable; proofs

are not supplied. SPMC does not endorse any

company, dealer or auction house.

Advertising Deadline: Subject to space availability,

copy must be received by the editor no later than the

first day of the month preceding the cover date of the

issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the March/April issue). Camera

ready art or electronic ads in pdf format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Space 1 Time 3 Times 6 Times

Fullcolor covers $1500 $2600 $4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Fullpagecolor 500 1500 3000

FullpageB&W 360 1000 1800

Halfpage B&W 180 500 900

Quarterpage B&W 90 250 450

EighthpageB&W 45 125 225

Required file submission format is composite PDF

v1.3 (Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted

files should conform to ISO 15930-1: 2001 PDF/X-1a

file format standard. Non-standard, application, or

native file formats are not acceptable. Page size:

must conform to specified publication trim size. Page

bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond trim for

page head, foot, front. Safety margin: type and other

non-bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”

Advertising copy shall be restricted to paper currency,

allied numismatic material, publications and related

accessories. The SPMC does not guarantee

advertisements, but accepts copy in good faith,

reserving the right to reject objectionable or

inappropriate materialoreditcopy.

The SPMC assumes no financial responsibility for

typographical errors in ads, but agrees to reprint that

portion of an ad in which a typographical error occurs

upon prompt notification.

Benny Bolin, Editor

Editor Email—smcbb@sbcglobal.net

Visit the SPMC website—www.SPMC.org

Misspelling Error on $1000 Series 1882 Gold Certificates

Peter Huntoon ............................................................... 368

Progression to the Misspelling Error

Peter Huntoon. ............................................................. 374

The Farmers& Merchants National Bank

David Hollander ............................................................ 379

Zambia – “Chain Breaker”

David B. Lok ..................................................................... 390

Plate Numbers on Series 2000 $10 FRNs

Joe Farrenkopf ............................................................ 395

A Montgomery Mystery

Bill Gunther ................................................................. 414

Oak Hill Store

Ronald Horstman ........................................................ 420

Uncoupled—Joe Boling & FredSchwan……………………..…423

Small Notes—R&S $1 1935A Experimentals ....................... 431

Cherry Pickers Corner—Robert Calderman ....................... 436

Chump Change--Loren Gatch ............................................... 439

Quartermaster Column—Michael McNeil ............................ 440

Obsolete Corner--Robert Gill ................................................ 442

President’s Message ........................................................... 445

New Members ....................................................................... 446

Money Mart .............................................................................. 447

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

365

Society of Paper Money Collectors

Officers and Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS:

PRESIDENT--Shawn Hewitt, P.O. Box 580731,

Minneapolis, MN 55458-0731

VICE-PRESIDENT--Robert Vandevender II, P.O. Box 2233,

Palm City, FL 34991

SECRETARY--Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mtn., Rd. #197,

Chattanooga, TN 37405

TREASURER --Bob Moon, 104 Chipping Court,

Greenwood, SC 29649

BOARD OF GOVERNORS:

Mark Anderson, 115 Congress St., Brooklyn, NY 11201

Robert Calderman, Box 7055 Gainesville, GA 30504

Gary J. Dobbins, 10308 Vistadale Dr., Dallas, TX 75238

Pierre Fricke, Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776

Loren Gatch 2701 Walnut St., Norman, OK 73072

Joshua T. Herbstman, Box 351759, Palm Coast, FL 32135

Steve Jennings, 214 W. Main, Freeport, IL 61023

J. Fred Maples, 7517 Oyster Bay Way,

Montgomery Village, MD 20886

Michael B. Scacci, 216-10th Ave., Fort Dodge, IA 50501-2425

Wendell A. Wolka, P.O. Box 5439, Sun City Ctr., FL 33571

APPOINTEES:

PUBLISHER-EDITOR--Benny Bolin, 5510 Springhill Estates Dr.

Allen, TX 75002

ADVERTISING MANAGER--Wendell A. Wolka, Box 5439

Sun City Center, FL 33571

LEGAL COUNSEL--Robert J. Galiette, 3 Teal Ln.,ssex, CT 06426

LIBRARIAN--Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mountain Rd. # 197,

Chattanooga, TN 37405

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR--Frank Clark, P.O. Box 117060,

Carrollton, TX, 75011-7060

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT--Pierre Fricke

WISMER BOOK PROJECT COORDINATOR--Pierre Fricke,

Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776

The Society of Paper Money Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit organization under

the laws of the District of Columbia. It is affiliated

with the ANA. The Annual Meeting of the SPMC i s

held in June at the

International Paper Money Show.

Information about the SPMC,

including the by-laws and

activities can be found at our website, www.spmc.org. .The SPMC

does not does not endorse any dealer, company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and LIFE. Applicants must be at

least 18 years of age and of good moral character. Members of the

ANA or other recognized numismatic societies are eligible for

membership. Other applicants should be sponsored by an SPMC

member or provide suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR. Applicants for Junior membership must

be from 12 to 17 years of age and of good moral character. Their

application must be signed by a parent or guardian.

Junior membership numbers will be preceded by the letter “j” which

will be removed upon notification to the secretary that the member

has reached 18 years of age. Junior members are not eligible to hold

office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues for members in Canada and

Mexico are $45. Dues for members in all other countries are $60.

Life membership—payable in installments within one year is $800

for U.S.; $900 for Canada and Mexico and $1000 for all other

countries. The Society no longer issues annual membership cards,

but paid up members may request one from the membership director

with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who joined the S o c i e t y

prior to January 2010 are on a calendar year basis with renewals due

each December. Memberships for those who joined since January

2010 are on an annual basis beginning and ending the month joined.

All renewals are due before the expiration date which can be found on

the label of Paper Money. Renewals may be done via the Society

website www.spmc.org or by check/money order sent to the treasurer.

Pierre Fricke—Buying and Selling!

1861‐1869 Large Type, Confederate and Obsolete Money!

P.O. Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776 ; pierrefricke@buyvintagemoney.com; www.buyvintagemoney.com

And many more CSA, Union and Obsolete Bank Notes for sale ranging from $10 to five figures

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

366

For more information about consigning to Kagin’s upcoming 2019 auctions

contact us at : kagins.com, by phone: 888-852-4467 or e-mail: Nina@kagins.com.

Contact Nina@Kagins.com or call 888.8Kagins to speak directly to Donald Kagin, Ph.D. who will arrange

to visit you and appraise your collecti on free and without obligati on.

Consign with The O cial Auctioneer

of the ANA National Money ShowsTM

March 28-30, 2019

David L. Lawrence Convention Ctr, Pittsburgh, PA

Limited Space available for your consignment alongside these:

Let Kagin’s tell your personal numismatic story and create a lasting legacy for

your passion and accomplishments!

RECORD

PRICES

REALIZED!

99% Sell Through

National Bank Note Collection

Experience the Kagin’s Di erence:

- 0% Seller’s Fee

- Unprecedented up to 6 months of Marketing and Promotion of your consignment

- Innovative marketing and research as we did with the “Saddle Ridge Hoard Treasure” and the

1783 Quint—The rst American coin

- Groundbreaking programs including the rst ever Kagin’s Auctions Loyalty Program that gives

buyers 1% back in credit

- Free educational reference books and memberships

The Joel Anderson Collection

of the #1 Registry Set of

Treasury Notes of the

War of 1812:

The First

circulating

U.S. Bank Note

The Carlson Chambliss Collection:

Fractional Currency

Collection

New Zealand Currency

Collection

Israeli

Currency

Collection

Encased Postage Stamps

Kagins-PM-Ad NMS-Cons-10-15-18.indd 1 10/15/18 11:11 AM

Misspelling error

on $1000 Series of 1882

Gold Certificates

Introduction and Purpose

Doug Murray, while perusing the scans of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing proofs on the

Smithsonian website, discovered that the word Thousand is misspelled “Thonsand” in the “One Thousand

Dollars” banner on the proofs for all the $1000 Series of 1882 gold certificates, including the countersigned

variety.

The misspelling was acknowledged on the last proof made for the $1000s in the series—a proof

lifted from a Lyons-Treat plate upon which someone at the Bureau of Engraving and Printing sketched a

correction on the A-subject. However, the mistake had been detected over 15 years earlier because the

identical banner was corrected on $1000 Series of 1890 and 1891 Treasury notes.

It is the purpose of this article to describe the occurrence of this mistake and reveal how it was

produced.

The $1000 Misspelling

The plates for the Series of 1882 gold certificates were designed and master dies made for them

The Paper

Column

by

Peter Huntoon

Doug Murray

Figure 1. Series of 1882 gold certificate, all of which contain the misspelling “Thonsand” in the banner

underneath the Treasury seal. Smithsonian photos.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

368

during the heyday of the reign of Bureau of Engraving and Printing Chief Engraver George Casilear. The

notes incorporate lines of text and numbers made using Casilear’s patented lettering technology. The

concept was that full alphabets of letters and/or numbers were designed and engraved on a die, each alphabet

consisting of a specific font. The characters were then taken up one at a time on a transfer roll. When text

was needed on a die or plate, the required characters were efficiently laid-in one character at a time to

compose the text instead of having the text hand-engraved by a letter engraver (Huntoon, 2018). In this

manner, the same font could be reused on any number of Bureau products.

Classic examples on the face of the note illustrated on Figure 1 include “THIS CERTIFIES THAT,”

“GOLD CERTIFICATE,” “DEPARTMENT SERIES,” “Gold Coin,” “WASHINGTON, D.C.,” and the

letters and numerals used in the corner counters. One of the most distinctive of the fonts reproduced by

Casilear’s patented lettering process was that used to spell out GOLD CERTIFICATE on the back of the

note. All the other letters and numerals on the back also were laid-in using the patented lettering process

including the large M.

However, the banner “One Thonsand Dollars,” which is the focus of this article, was not composed

using the patented lettering process. In contrast, that line of text was hand-engraved on a component die by

a letter engraver as a one-off job. This is evident if you will carefully examine the three occurrences of the

letter n in the banners illustrated on Figures 2 and 3. Notice that the crossbars at the tops differ in detail,

something that could not occur if laid-in from one n from one of Casilear’s character rolls.

What transpired in the case of the misspelled line is that it was engraved only once, lifted on a roll

from the component die upon which it was engraved, and then transferred to the generic full-face master

dies for both the countersigned and non-countersigned varieties of the $1000 notes. This type of recycling

of text was a common practice in the bank note industry.

The completed images on the two generic full-face master dies, which included everything except

the Treasury signatures and plate serial number, were picked up on master rolls that were used to lay-in the

generic designs of the notes onto the required plates. The plate-specific Treasury signatures were rolled in

separately and plate numbers probably etched in.

All the proofs for the $1000 Series of 1882 gold certificates are listed on Table 1. A total of six

plates were made but additional proofs were lifted because the Treasury signatures were altered on some.

Bureau personnel didn’t harden such little-used plates, which allowed alterations to be made with relative

ease.

The Mistake is Acknowledged

After poring over the proofs several times, Murray spotted the sketched U on the A-note on the

proof lifted from the second Lyons-Treat plate illustrated on Figure 5. The image is from Treasury plate

number 21325, plate serial number 5.

We have no way of knowing if the sketch was made before or after the plate was certified on

Figure 2. Misspelled Thonsand as it appears on all $1000 Series of 1882 gold certificates. Notice the differences

in the crossbars at the top of the letter n, which occurs three times in the line. The differences reveal that the

line was engraved instead of being laid-in one letter at a time. In contrast, “IN” and “Gold Coin” were laid-in

one letter at a time using Casilear’s patented lettering process.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

369

February 7, 1906. Significantly, BEP Director William M. Meredith’s initials were not crossed out to cancel

the certification. No second proof was lifted from plate 5 to reveal that the misspelling was corrected.

A total of 27 $1000 Series of 1882 gold certificates are recorded in Gengerke’s census, four of

which are Lyons-Treat notes. The highest serial number among them is D15131 from plate 4. The last serial

number used in the series was D16000. Plate 5 never was sent to press.

A Joker

The fact is that the misspelling on the 1882 gold notes was old news at the Bureau of Engraving

and Printing by 1906. Lee Lofthus, while reviewing this article, pointed out that the same One Thousand

Dollars engraving was recycled to the faces of the $1000 Series of 1890 and 1891 Treasury notes, except

the misspelling was corrected on them as illustrated on Figure 6. Consequently, the problem had been

caught over a decade and a half earlier.

Furthermore, a smaller version of the engraving was adapted for the 1890 backs but with a peculiar

twist. A crossbar was correctly added to the bottom of the u but left on the top. See Figure 7.

Evidently when it came to the 1890 and 1891 Treasury notes, a new die with the banner was laid-

in from the roll lifted from the original and the u repaired before the die was hardened. A new roll was lifted

from the new die, hardened and used to lay the correctly spelled banner into the generic master die made

for the $1000 Treasury note faces.

Although very straight forward, this explanation begs the question of why they didn’t change it on

the Series of 1882 gold certificates. The problem they faced was that the full-face generic die and roll they

Figure 3. Misspelled Thonsand as found on the countersigned version of the $1000 Series of 1882 gold

certificates (Fr.1218a). Notice that every detail in “One Thonsand Dollars” is identical to that on Figure 2

revealing that the line of text was reproduced from the same component die.

Table 1. Record of all the proofs lifted from the $1000 Series of 1882 gold certificate

plates used in the series, all with the spelling "Thonsand." All were 4-subject plates.

Treas. Pl. # Pl. Ser. # Register Treasurer Cert. Date Status Special Consideration

none 1 Bruce Gilfillan Sep 16, 1882 new plate countersigned version

814 1 Bruce Gilfillan Nov 23, 1882 new plate Treasury plate no. in pencil

814 1 Bruce Wyman no date sig change Treasury plate no. in pencil

814 1 Rosecrans Hyatt no date sig change

814 1 Rosecrans Hyatt no date re-entry

814 1 Rosecrans Hyatt no date re-entry

814 1 Rosecrans Huston Mar 18, 1891 sig change

814 1 Rosecrans Huston no date re-entry

814 1 Rosecrans Nebeker Jan 28, 1892 sig change

9426 2 Lyons Roberts Aug 21, 1899 new plate

13548 3 Lyons Roberts Jan 19, 1904 new plate

21310 4 Lyons Treat Jan 29, 1906 new plate

21325 5 Lyons Treat Feb 7,1906 new plate misspelling flagged on A-subject

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

370

had for the gold certificates already were hardened so could not be altered.

The fact is that nothing was done about the misspelling on the $1000 gold certificates so the tack

taken by those in the know was to let sleeping dogs lie.

Curiosity

Murray had the distinct advantage of looking at naked proofs, which facilitated his ability to spot

the error, but so did the trained and critical plate inspectors who scrutinized the first proofs back in 1882

who missed it.

The big surprise for us is the fact that no numismatist ever published on the misspelling. More than

half of the reported Series of 1882 $1000 gold certificates are in collector hands and collectors tend to

intently study their notes. However, when you glance at text, you tend to see it as it should be. Those who

own varieties with a large seal certainly can be forgiven for missing it because the seal obscures the

offending character. However, the misspelling is fully exposed on the more common variety with small

seals as per Figure 8.

References Cited and Sources of Data

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1863-1958, Certified proofs of U. S. currency printing plates: Division of Numismatics,

American Museum of History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Sep 9, 1905-Sep 20, 1907, Historical Record of Plates in the United States and Miscellaneous

Vault, plates 20515-25290: Record Group 318, UD1, entry 1, volume 24, U. S. National Archives, College Park, MD.

Gengerke, Martin, on-demand, The Gengerke census of U. S. large size currency: gengerke@aol.com.

Huntoon, Peter, Mar-Apr 2018, Patented lettering on Bureau of Engraving and Printing products: Paper Money, v. 57, p. 93-107.

Figure 4. Proof of

the countersigned

version of the $1000

Series of 1882 gold

certificates payable

at the Assistant

Treasurer’s office in

New York. Thomas

C. Action hand-

signed the issued

notes. The seals on

the issued notes did

not obscure the

misspelling.

Smithsonian photo.

Figure 5. Sketched correction that appears on the A-subject of Lyons-Treat plate 21325/5, which was the last

$1000 plate made for the series. The plate was certified February 7, 1906 despite the misspelling.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

371

Figure 6. Series of 1891 Treasury note with small scalloped seal that allows you to see the

entire One Thousand Dollar banner, which was recycled to this design but with the correct

spelling of Thousand. Smithsonian photo.

Figure 8. Series of 1882 gold certificate with a small scalloped seal that does not cover the

misspelling of Thousand in the banner. These seals were used on Rosecrans-Nebeker, Lyons-

Roberts and Lyons-Treat notes. Heritage Auction Archives photo.

Figure 7. Series of 1890 Treasury note back. The banner here is a look-a-like but different,

smaller engraving where the misspelling has been partially corrected by adding a crossbar to

the bottom of the u but erroneously leaving it at the top. This is curious! Smithsonian photo.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

372

Progression to the Misspelling Error on

$1000 Series of 1882 Gold Certificates

by

Peter Huntoon, Doug Murray & Lee Lofthus

Introduction and Purpose

The presentation of the letter u in the word thousand became progressively more ambiguous on

large size notes employing a similar Gothic font to spell out thousand until the u morphed into an n on the

$1000 Series of 1882 gold certificates. The purpose of this article is to illustrate this progression and the

steps taken to right the problem after it occurred.

Significantly, thousand was spelled correctly on the Series of 1882 $5,000 and $10,000 payable in

New York notes that employed banners made with the same Gothic font as used on the $1000s. A separate

die was engraved for each denomination, thus explaining why the mistake was confined to the $1000s.

This article is designed to be a companion and supplement to the preceding article in this volume.

Gothic Thousand

Figure 1 illustrates the word thousand from every series of large size high denomination note that

Figure 1. Occurrences on large size U. S. currency of the word thousand spelled out in similar Gothic letters.

Notice that the outcome on the GC 1882 $1000s was the misspelling Thonsand.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

374

employed a similar Gothic font to spell out the word. All were engraved at the Bureau of Engraving and

Printing except the 1862/3 legal tender face, which was prepared at the American Bank Note Company.

Six distinct engravings were involved, respectively:

1 $1000 legal tender 1862/3

2 $1000 gold certificates 1863, 1870, 1875

3 $1000 gold certificate 1882 & $1000 Treasury note 1890/1

4 $5000 gold certificate 1882

5 $10000 gold certificate 1882

6 $1000 Treasury note 1890 back.

The engraving used for the $1000 Series of 1882 gold certificates and Series of 1890/1 Treasury

notes was the same except the misspelling was corrected on the Treasury notes.

A characteristic of Gothic fonts is that the letters are dominated by bold vertical strokes. Individual

letters composed of two or more vertical strokes, such as o, n and u, utilize caps and boots on the strokes

with shapes that visually appear to connect the verticals yet sometimes don’t. This is particularly evident

in the lowercase o in both Thousand and Dollars in the LT 1862/3 and GC 1863,1870 & 1875 examples on

Figure 1. Notice that the black parts of the two halves of the o don’t actually connect in the ABNC engraving

and barely touch in the first BEP engraving. Our minds forge those connections thanks to the use of clever

foreground white outlining and fine-line background shading by the engravers.

The u on the GC 1863, 1870 and 1875 engraving is more ambiguous than on the ABNC rendering

because the caps on the top of the two strokes actually touch whereas those of the boots don’t. The u and n

are barely distinguishable save for some subtle differences in outlining and shading. See Figure 2. This

particular engraving represents an intermediate between the LT 1863 and GC 1882 $1000s. Once we arrive

at the GC 1882 $1000, the n and u are all but indistinguishable so Thousand became Thonsand.

The engravings for the GC 1882 $5000 and $10000 eliminated all confusion because the u is well

formed on both. A careful letter-by-letter comparison between the GC 1882 $1000, $5000 and $1000

engravings reveals that each is a distinct engraving.

It is obvious that the misspelling on the GC 1882 $1000s was recognized by the time the Series of

1890 Treasury notes were being designed because they used the same engraving but corrected the spelling.

The process used to make the correction is described in the preceding article.

The engraving used on the back of the 1890 TN $1000s was an entirely new but smaller replica of

that on the face. They were careful to avoid the spelling problem on it.

Photo Gallery

The $1000 proofs illustrated on Figures 3 through 7 were not shown in our companion article.

Figures 8 through 10 are proofs of the $5000 and $10000 Series of 1882 gold certificates that were payable

in New York. We thought you would enjoy seeing these because the issued notes are virtually unobtainable

owing to their high face value and the fact that most were redeemed.

Sources for Photos

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1863-1958, Certified proofs of U. S. currency printing plates: Division of Numismatics,

American Museum of History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

Heritage Auction Archives: https://www.ha.com

Figure 2. Notice the subtle means

used to connect the tops and

bottoms of the bold vertical

strokes within letters. The u and

n are virtually indistinguishable

here.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

375

Figure 3. Face

used on $1000

1862/3 legal

tender notes.

Heritage

Archives

photo.

Figure 5. Face

used on $1000

1863 gold

certificates.

Smithsonian

photo.

Figure 6. Face

used on $1000

Series of 1870

gold

certificates.

Smithsonian

photo.

Figure 4. Back used on $1000 1863, 1870

and 1875 gold certificates. Smithsonian

photo.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

376

Figure 7. Face

used on $1000

Series of 1875

gold

certificates.

Smithsonian

photo.

Figure 8. Face

used on $5000

Series of 1882

gold

certificates

payable in

New York.

Smithsonian

photo.

Figure 9. Face

used on

$10000 Series

of 1882 gold

certificates

payable in

New York.

Smithsonian

photo.

Figure 10. back used on $10000

Series of 1882 gold certificates.

Smithsonian photo.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

377

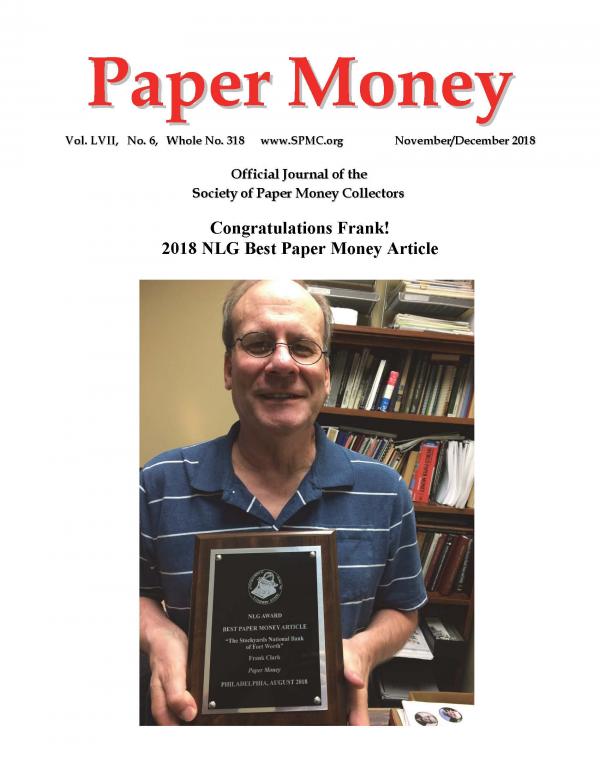

Congratulations to Our Winners...

This group of collectors deserve special recognition for standing out among such highly competitive sets.

Chosen for the quality of their set presentation and composition, the winners will receive a plaque, and

their winning set will be adorned with a winners’ icon on the PMG Collectors Society site.

To learn more about membership and PMG Registry participation, visit PMGnotes.com/registry

THE NINTH ANNUAL

PMG REGISTRY AWARDS

Best US Set

Jack Ackerman:

$5 Federal Reserve Note - District Set with Stars and Varieties

Best World Set

Atul Kumar Singh:

India Complete Type Set, 1917-Date, P1-Date

Best Presented Set

Meso Numismatics:

Banco Central De Costa Rica, 1950-Date, P215-Date

Overall Achievement Award

dustycat

Honorable Mention

Jerry and Diane Fishman Collection

PMGnotes.com | 877-PMG-5570

18-CCGPA-4564_PMG_Ad_RegistryWinners_PaperMoney_NovDec2018.indd 1 9/26/18 2:19 PM

The Farmers & Merchants National Bank of Huntsville,

Alabama, 1892‐1905

HUNTSVILLE’S NATIONAL BANKS.1

Like the great majority of national banks

throughout the country, the story of those in

Huntsville (Table 12) is one of extended families

or long‐term business relationships. In the case

of The Farmers & Merchants National Bank of

Huntsville, Alabama, it was built solely upon

business associations among men who migrated

in the late 19th century to Huntsville, Madison

County, Alabama, from Pierre, South Dakota.

Table 1: Huntsville Was Home to Four National Banks During the Note Issuing Period.

Charter

No.

Title Chartered Fate

1560 The National Bank of

Huntsville

September 15, 1865 Liquidated, July 3, 1889

4067 The First National Bank

of Huntsville

June 22, 18893 March 23, 1985, Changed to

a Domestic Branch of a

Domestic Bank4

4689 The Farmers &

Merchants National

Bank of Huntsville

January 25, 1892 Liquidated, March 16, 1905

8765 The Henderson

National Bank of

Huntsville

June 1, 1907 August 31, 1985, Changed to

a Domestic Branch of a

Domestic Bank5

CHARTER 4689: THE FARMERS & MERCHANTS NATIONAL BANK OF HUNTSVILLE WAS HUNTSVILLE’S

SHORTEST‐LIVED BANK.

Several businessmen…COL 6 Willard Irvine

Wellman, COL Tracy Wilder Pratt7, and William

Sherley Wells8…doing business in Pierre, South

Dakota…heard about opportunities in Huntsville,

Alabama, and moved south in 1891‐1892 to

exploit them.9

Among their many ventures, they 10

founded The Farmers & Merchants National

Bank. Because of its short, 13‐year, existence,

the bank made no lasting impact on the

Huntsville community. In fact, today its existence

appears to be lost in history. However, the bank

officers and their colleagues did make significant

contributions to the city, to Madison County, and

to the northern part of the state.

THE BANK. The Farmers & Merchants

National Bank was organized January 20, 1892,

with $100,000 in capital stock. (See Figure 111.)

COL Wellman was elected President and Mr.

Sidney Jonathan Mayhew, a northerner living in

Huntsville since the Civil War, Vice President. The

Board of Directors consisted of Mr. Milton

Humes, a lawyer from Virginia and president of

the Board of Trade12; Mr. Charles Henry Halsey;

Mr. Mayhew; Mr. Oscar Richard Hundley, a

financier and politician; Mr. Henry McGee, who

came from Philadelphia in 1866 and operated

the McGee Hotel starting in 1869; Mr. C. L. Nolen,

a northerner living Huntsville since

Reconstruction; Judge David Davie Shelby; Mr.

By David Hollander

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

379

William Sherley Wells of Pierre, South Dakota,

where he was a Railroad President; and COL

Wellman. The Cashier was Edward Hotchkiss

Andrews. (See Tables 2 and 3.13) The bank was

located in the Halsey Building opposite the

Huntsville Hotel on Jefferson Street.14

The bank seemed to have operated

normally during its first years. However, the first

clear evidence of financial problems was the

receipt of the July 30, 1901, “Notice of

Impairment” from the United States Treasury

Department in the not‐inconsequential amount

of $30,000 (Figure 215). One may assume the

bank satisfied the Treasury Department because

it remained in business for almost four more

years.

Another compelling indication of potential

financial issues with the bank occurred as a

result of Act 374 (February 12, 1901) of the

Alabama General Assembly incorporating the

“Heralds of Liberty” in Huntsville, Alabama. The

trustees were Tracy Wilder Pratt, Willard Irvine

Wellman, and James Richardson Boyd. This was

ostensibly a fraternal benefit society. However,

in reality, it was a front company, headquartered

in Philadelphia, that allowed the Heralds of

Liberty to evade state insurance regulations. The

parent company’s officers adopted a variety of

schemes to embezzle funds from the fraternity

by selling worthless bonds, borrowing money

with insufficient collateral, and having the

Heralds make “payments” to the parent. It took

20 years of illegal practices, resulting in an excess

of unpaid claims, before the Alabama Insurance

Department took over the fraternity in June

1921.16 Prior to 1921 and even after the ruse

exploded, the general public was unaware of the

issues involving the Heralds of Liberty and the

reputations of the key figures were not sullied.

Whether the Huntsville trustees’

involvement was merely innocent or part of a

larger conspiracy is unknown, but the latter case

seems quite likely. These financial shenanigans

may have contributed to the sale of the bank.

On March 16, 1905, the bank was sold to

the Huntsville Bank & Trust Company.17

Figure 1: The Bank Opened for Business in 1892.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

380

Figure 2: By 1901 There Were Obvious Financial Issues at the Bank

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

381

Table 2: The Farmers & Merchants National Bank of Huntsville Had a Single President.

Year President Born Died Spouse

1892‐1905 Willard Irvine Wellman 11/2/1858 3/23/1922 Helen L. Leet

Table 3: There Were Two Cashiers During the Bank’s Existence.

Year Cashier Born Died Spouse

1892 Edward Hotchkiss Andrews 2/22/1863 4/9/1932 Emma Yaste

1898 James Richardson Boyd 4/14/1860 11/4/1907 Elizabeth “Bettie”

Watkins Mathews

WILLARD IRVINE WELLMAN (Figure 318) was

born in Farmington, Minnesota,19 November 2,

1858.20 On March 6, 1884, he married Helen L.

Leet (January 27, 1865‐September 12, 1934) in

Rochester, Minnesota.

COL Wellman moved to Pierre, South

Dakota, where he teamed with COL Pratt and

Mr. Wells in several businesses, including the

Northwestern Land Association (Figures 421 and

522), a South Dakota corporation23. In 1892 the

three of them moved to Huntsville.

In Huntsville COL Wellman’s activities

included realty, insurance, banking (Figure 724),

textile mills25 and 26, and civic involvement27 and 28.

He died March 23, 1922, and is buried in

Huntsville’s Maple Hill Cemetery.29

Figure 3: Willard Irvine Wellman (left) and Tracy Wilder Pratt

(right) Were Longtime Business Partners.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

382

Figure 4: The Pierre, South Dakota, 1890‐1891 Directory Confirms that COL Wellman, COL

Pratt, and Mr. Wells Were Business Partners in South Dakota.30

Figure 5: COL Wellman Was the Secretary of the Northwestern Land Association.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

383

EDWARD

HOTCHKISS

ANDREWS

(Figure 6 31 ) was

born February 22,

1863, in Cazenovia,

New York. His

father was a well‐

known Methodist

minister and was

assigned to many

different

pastorates. It was

in the various

towns where his

father was a

minister that Mr.

Andrews secured

his education in

the public schools. He completed his instruction

at Wesleyan University, Middletown,

Connecticut. Then followed several years of

varied experience while he was trying to find the

particular calling to which he was best fitted. He

became an Assistant Geologist for the US

Geological Survey during 1884‐1886.

On October 5, 1886, he married Miss Emma

Amelia Yaste (January 26, 1864‐March 30, 1947)

in Washington, DC.

For five years, 1886‐1891, he was a banker

in Pierre, South Dakota (where he probably met

COL Wellman, COL Pratt, and Mr. Wells). For

climatic reasons he came to Alabama in 1891 and

spent five years in the banking business in

Huntsville as the Cashier of the Farmers &

Merchants National Bank.

Figure 7: As the President of the Farmers & Merchants Bank, COL Wellman Was

Authorized to Issue Stock to Himself.

Figure 6: Mr. Andrews Was

the Cashier Until 1898.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

384

In 1898 Mr. Andrews resigned as the

Huntsville bank Cashier and started his insurance

career in Mobile as manager of the Central Life

Insurance Company of Cincinnati. He was forced

to leave Mobile during an epidemic of yellow

fever and became a permanent resident of

Birmingham. In 1896 he was the State of

Alabama Manager of the Union Central Life

Insurance Company, Cincinnati, Ohio, and

developed 27 subordinate agencies, comprising

one of the largest general insurance agencies in

the South.

For two years Mr. Andrews was president of

the Birmingham Council of the Boy Scouts of

America. He was a Mason and in 1918 was

President of the Rotary Club, a member of the

board of governors of the Country Club, and a

member of the Southern and Roebuck clubs.

During World War I he became a member of

Headquarters Company of the Fifty First Infantry.

He was one of the men who saw active service at

the front in France.32

Mr. Andrews died April 9, 1932, and is

buried in Birmingham, Alabama’s Elmwood

Cemetery.

JAMES RICHARDSON BOYD (Figure 833) was

born in Jackson, Mississippi, April 14, 1860.

He came to Huntsville in the late 1890’s to

work as a clerk in the First National Bank of

Huntsville, where his uncle, MAJ James

Richardson34 Stevens, Sr., was President.35

After Mr. Andrews’ resignation in 1898, Mr.

Boyd was elected to be Cashier of the Farmers &

Merchants National Bank.

He married Elizabeth “Bettie” Watkins

Mathews (March 29, 1876‐November 8, 1951)

April 29, 1901, in Huntsville. They had one child,

James Richardson Boyd, Jr. (September 1, 1902‐

March 16, 1981).

When the Farmers & Merchants National

Bank was sold to the Huntsville Bank & Trust

Company in 1905, Mr. Boyd continued his career

as the Cashier at the new bank.

He was an esteemed and trusted member

of the Huntsville community. For instance, the

Madison Spinning Mill was placed in his hands as

receiver through bankruptcy proceedings in the

United States District Court. Further, he was a

member of the Huntsville City Council for eight

years, his last term expiring in April 1907. In

September 1907 he was elected as President of

the Huntsville City Council even though he had

not been a candidate.36

However, during his last year of life, Mr.

Boyd borrowed extremely heavily (thousands of

dollars) from the Huntsville Bank & Trust

Company; the Hamilton National Bank,

Chattanooga, Tennessee; and the Peoples

National Bank of Shelbyville, Tennessee. Some of

his loans were co‐signed by COL Wellman.

He committed suicide on November 4,

1907.37 At the time it was assumed the strain of

his work was the reason for him killing himself;

however, during probate 38 it became obvious

that he must have been very depressed and

despondent about his enormous debts. He died

intestate. His estate was deemed insolvent and

his creditors, including his widow, his son, and

COL Wellman, were reimbursed by Probate

Court order at the rate of $0.21 per $1.00.39

Mr. Boyd is buried in Huntsville’s Maple Hill

Cemetery.

.

Figure 8: Mr. Boyd Was Cashier

from 1898 Until the Bank Was

Sold in 1905.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

385

THE BANKNOTES. Records indicate that at

least $22,500.00 of the $95,600.00 printed were

on the balance sheet as liabilities, which one may

assume entered circulation. (See Figure 9.40)

There are no known surviving notes from

the Farmers & Merchants National Bank. Only

the approved proofs of the notes are known.

(See Table 441 and Figure 1042.)

Table 4: No Surviving Notes Are Known from the Farmers & Merchants National Bank.

Series Denomination

Serial

Numbers

Notes

Printed

Total Value Known

1882

Brown

Back

$10 and $20, printed

in sheets of three

$10’s and one $20

1‐1912 $10=5,736

$20=1912

$10=$57,360.00

$20=$38,240.00

0

Totals: 7,648 $95,600.00 0

Total Unredeemed Notes in 1910: $2,850.00

Figure 9: In 1895 $22,500 of the National Bank Notes Were Listed as Liabilities.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

386

Figure 10: Banknote Proofs of The Farmers & Merchants National Bank of Huntsville,

Alabama, Are in the Smithsonian Institute.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

387

1 Hollander, David, “The National and First National Banks of Huntsville, Alabama, 1865‐1935,” Paper Money, 2017,

Volume 56, Number 312, Page 426. This was the first article in the series “Huntsville’s National Banks.”

2 Kelly, Don C., NATIONAL BANK NOTES, SIXTH EDITION, Oxford, Ohio: The Paper Money Institute, Inc., Copyright

2008, Page 33.

3 Floyd, W. Warner, Form 10‐300, Revision 6‐72, United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service,

National Register of Historic Places Inventory‐Nomination Form, signed July 19, 1974, Certified October 25, 1974.

4 Federal Reserve System, National Information Center,

http://www.ffiec.gov/nicpubweb/nicweb/InstitutionHistory.aspx?parID_RSSD=72632&parDT_END=20100129

5 Federal Reserve System, National Information Center,

http://www.ffiec.gov/nicpubweb/nicweb/InstitutionHistory.aspx?parID_RSSD=140830&parDT_END=19851130

6 The Huntsville Daily Times, Thursday, March 23, 1922, Page 1. This news report about COL Wellman’s death is the

only reference seen showing his title as “COL” rather than “Mr.”. It is assumed that the titles for both COL Wellman

and COL Pratt were honorary, neither could be confirmed.

7 The Community Builder, Huntsville, Alabama, October 31, 1928, Page 1. COL Tracy Wilder Pratt (September 1,

1861‐October 29, 1928) died suddenly of “heart failure” while sitting in his home and listening to the radio.

8 The Daily Mercury, Huntsville, Alabama, March 1, 1900. Mr. William Sherley Wells (1839‐February 28, 1900)

suffered from Pneumonia for six days and unexpectedly died. He was a native of Elmira, New York, and moved to

Forrest, City, Minnesota. In 1892 he moved to Huntsville, Alabama.

9 www.familysearch.org and www.ancestry.com. The three men were probably well‐acquainted prior to moving to

South Dakota because they had roots in the same area of Minnesota.

10 COL Wellman, COL Pratt, and Mr. Wells were involved together in a variety of businesses, sometimes overtly and

sometimes as silent partners. One assumes that COL Pratt was involved with the bank’s founding, but there is no

tangible evidence.

11 The Weekly Mercury, Huntsville, Alabama, February 3, 1892, Page 5.

12 Record, James, A DREAM COME TRUE, THE STORY OF MADISON COUNTY AND INCIDENTALLY OF ALABAMA AND

THE UNITED STATES, VOLUME II, John Hicklin Printing Company, Huntsville, Alabama, copyright 1978, page 80.

13 www.familysearch.org, www.ancestry.com, and www.findagrave.com.

14 Op. Cit., Record, Page 82.

15 Huntsville Madison County Public Library, Archives.

16 ACTS OF THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF ALABAMA PASSED AT THE SESSION OF 1900‐1901, HELD IN THE CITY OF

MONTGOMERY, COMMENCING TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 30, 1900. A. Roemer, Printer for the State of Alabama,

Montgomery, Ala., 1901, Pages 990‐1994.

17 The Huntsville Bank & Trust Company was formed in the late 1890’s with Sidney Jonathan Mayhew (May 28,

1829‐May 17, 1912) as the President. The bank was housed in the old Huntsville Hotel Corner (13 North Side,

Public Square) until it burned in 1908 at which time it moved into the Herstein Building until February 1930. Its

then President, Richard Holland Gilliam, Sr. (October 7, 1897‐January 24, 1976), sold the bank to the Henderson

National Bank of Huntsville (as reported by the Huntsville Daily Times on February 26, 1930).

18 Huntsville Madison County Public Library, Photograph Collection.

19 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter‐day Saints, "Pedigree Resource File," database, FamilySearch

(https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/2:2:37K6‐77Y : accessed 2016‐05‐22), entry for Willard I. /Wellman/.

20 There is some ambivalence in certain references about COL Wellman. For instance, in the United States Census

of 1900, his middle name is noted as “Quinn” and his year of birth as “1857.” In the same census and in the 1910

Census his wife’s name is recorded as “Hellen.”

21 Huntsville Madison County Public Library, Archives.

22 Huntsville Madison County Public Library, Archives.

23 Ryan, Patricia H., THE HUNTSVILLE HISTORICAL REVIEW, Volume, 15, Spring‐Fall 1985, Numbers 1 and 2,

Published by The Madison County Historical Society, “Tracy Pratt,” Page 28.

24 Huntsville Madison County Public Library, Archives.

25 Op. Cit., The Daily Mercury, July 21, 1900. THE LOWE MILL PLANS: COL Wellman received a letter from Mr.

Arthur Lowe stating that plans and specifications of the Lowe Mill would be at the Farmers & Merchants National

Bank and any contractor wanting to see them could do so at the bank. Mr. Lowe stated in his letter that he would

remain in the city until the mill was operational.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

388

26 The News Scimitar, Tennessee, November 4, 1918. COL Wellman was the treasurer of the Abingdon Mills and

was appointed receiver for the bankrupt company.

27 Op. Cit., The Daily Mercury, December 20, 1894. COL Wellman was a candidate for Mayor of Huntsville.

28 The Journal, Huntsville, Alabama, August 1, 1907. COL Wellman was elected to Huntsville’s first Board of

Education.

29 Op. Cit., The Huntsville Daily Times. At the time of his death COL Wellman was, among other positions, the

President of the Huntsville Bank & Trust Company, Treasurer and General Manager of Lincoln Mills, and Head of

the Huntsville Knitting Mills.

30 City Directory, 1890‐91, Pierre, South Dakota.

31 Birmingham Public Library, Digital Collections,

http://bplonline.cdmhost.com/digital/collection/p4017coll6/id/206/rec/1

32 Cruikshank, George M., A HISTORY OF BIRMINGHAM AND ITS ENVIRONS, Volume II, The Lewis Publishing

Company, Chicago and New York, c. 1920, Pages 215‐216.

33 Huntsville Madison County Public Library, Photograph Collection.

34 http://www.Ancestry.com. His maternal grandmother’s maiden name was “Richardson.”

35 The Weekly Mercury, Huntsville, Alabama, November 6, 1907, Page 3.

36 Ibid.

37 Ibid.

38 Madison County Records Center, Huntsville Madison County Public Library, “James Richardson Boyd” probate

records. Mr. Boyd left no last will and testament.

39 Ibid.

40 Annual Report of the Controller of the Currency, 1895.

41 Op. Cit., Kelly, Page 33.

42 The American History Museum of the Smithsonian Institute,

americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1453283.

I very much appreciate the advice and assistance from the Huntsville Madison County Public

Library, the Madison County Records Center, and William David Gunther.

SPMC Speaker Series

F.U.N. 2019

Come join us as we present multiple speaker sessions on Friday, January 11 2019 at F.U.N.

8a—Bob Moon--"A Beginner's Guide to Collecting National Currency"

9:30a—Wendell Wolka--“Enemy at the Gates: The Fall of New Orleans and its Numismatic

Consequences”

11a--Robert Calderman, "Introduction to Small Size Currency Collecting"

1230p--Pierre Fricke, “Counterfeit Confederate money made in the Union”

And join us for the SPMC membership meeting on Saturday January 12 at 0830.

Speaker TBA

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018* Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

389

Zambia

“Chain Breaker” Mpundu Mutembo 1936 – 100 Kwacha

by David B. Lok

(Zanco) Mpundu

Mutembo was born March

31, 1934 in the North-

Eastern city of Mbala,

Zambia, then known as

Northern Rhodesia, where

evidence of human

habitation in that area dates

back well into the ancient

past before written history.

When he was only 18

years old, Mutembo

dropped out of school and

joined the political struggle led by the politician

Robert Makasa, and it was then that he started writing

what would eventually be several books about the

damages that colonial administration had on the

country.

By 1957 Mutembo had already begun making a

name for himself in Northern Rhodesia as an activist

for political reform and was quite outspoken against

colonialism, for which he had been beaten and arrested

by government agents. Because of his commitment to

the political struggle, Mutembo was sent to Kenya to

assist Dedan Kimathi’s Mau uprising. Dedan had been

captured the previous year and was executed in early

1957 for his armed anti-governmental activities.

Seeing a fellow freedom fighter so committed to his

cause that he would risk death must have left an

impression upon the young Mutembo.

While in Kenya, Mutembo and his companions

were tasked with learning how to foment rebellion and

then return home and start the process there. It’s

unlikely that he learned much about the armed conflict

and guerrilla fighting that the Mau Mau uprising had

been doing, for when he returned, he worked closely

with Kenneth Kaunda (later the first president of

Zambia) and Simon Kapwepwe (later the first Vice

President), which placed him in a political sphere, not

a military one.

Nevertheless, Mutembo is well known for a

famous court case concerning a fight about his

political views during which he had been sorely beaten

and two of his teeth were knocked out. The judge

asked him to demonstrate how he was beaten, do

Mutembo walked over to the prosecution table, where

a colonial lawyer was seated, and punched the lawyer

in the face. For his actions, he was sentenced to 10

years in prison, with an additional punishment of four

lashes for striking the prosecutor.

Mutembo was held in Livingstone prison, and

while there he was reportedly forced to witness the

executions of three black men accused of murder. He

was later transferred to Mukobeko prison, where he

spent the rest of his sentence in comparative peace.

Back in the realm of politics, Mutembo’s role was

that of an opening act for the future president. He

would go out on stage before Kaunda would make an

appearance and fire up the audience by telling them

how bad the colonialist administrators were for the

country and to rally them to fight for independence

that, with Kaunda at the helm, could be achieved.

It was during a formative meeting on October 24,

1958 that the ZANC (Zambian African National

Congress) was formed. It was then that Mutembo got

a similar nick-name ‘’Zanco’’. But Mutembo was not

alone in receiving a new name; a new nation was being

formed by these young men, and that new nation also

needed a new name. In an interview many years later,

Mutembo recalled that Kaunda and Kapwepwe were

mulling over a couple of possible names. Inspired by

the Zambezi River, “Zambia” was proposed, and soon

it was being chanted over and over, and the decision

was made. The motto, “One Zambia, One Nation” was

also decided at that meeting.

‘Zanco’ Mpundu Mutembo

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

390

In the early 1960’s, Kenneth Kaunda drafted a

letter to then Governor Sir Arthur Benson, asking for

a change in the constitution that granted the Colonial

Europeans more power in the legislature. Mutembo

(Zanco) was tasked to deliver the letter, but when he

arrived at the governor’s office, he was arrested and

beaten. But by 3:00 pm that afternoon, he was back in

Kaunda’s offices where he was given a hero’s

welcome. 12 hours later he went to Cairo Road in

Lusaka and climbed a tree with his megaphone. Early

that morning he started denouncing the constitution,

and demanding it be changed. Police soon arrived and,

unable to talk him down, they threatened to shoot

Zanco if he did not stop. The threats of being shot were

enough, and Mutembo climbed down and was again

arrested. The tree later came to be known as the

“Zanco Tree”.

Then, on New Year’s Eve, 1963, Mutembo was

summoned by Kaunda and was told that he had been

chosen to die for the nation. One can only speculate

the thoughts and feelings that assuredly rushed into

Mutembo’s mind, such as his memory of Dedan

Kimathi’s execution in Kenya years ago. Perhaps this

gave him the strength to accept his fate. Together with

Kaunda, they rehearsed demands for independence

that Kaunda wanted him to make to the Rhodesian

Governor. There are no records of why he was told

this, nor what it could achieve, but he soon found

himself in a car with Sir Evelyn Hone, the last

Governor of Norther Rhodesia, en route to police

headquarters in Lusaka.

Sir Evelyn Hone, a Rhodes Scholar in the

Colonial Service, had served in Africa, islands in the

Indian Ocean, Middle East, and Central America. He

was the Chief Secretary to the Governor of Northern

Rhodesia from 1957 to 1959 and had been appointed

Governor in 1959. His primary role at the time was to

assist Northern Rhodesia to obtain independence

without resorting to the armed conflict which had

resulted in Kenya. To start off, Hone opened talks with

African nationalists, including Kenneth Kaunda,

which might explain how his actions have been

reported below.

Mutembo was brought into an interview room

inside the police station where he was interrogated. He

was afterwards taken into another room, this one filled

with reporters and photographers standing by. More

concerning though was the 18 armed officers lined up,

waiting for him. Mutembo was then fettered with a

heavy chain and was given an order to break free from

the chain, or to be shot.

Most people would have given up then and there

and waited for the bullets to send him to his death.

Breaking a small chain is hard enough, but the heavy

chain he was shackled to was quite large. Mutembo

however, started to pull. Perhaps he did not want to die

without the notoriety that Dedan Kimathi had achieved

in Kenya. Perhaps he acted as instructed by Kaunda,

after informing him of his fate. Whatever the reason,

Mutembo raised his arms and pulled, harder and

harder. The photographers started taking photos, and

Mutembo continued to pull on the chains. Eventually,

the chain broke. The Governor raised his hands in

amazement and declared: “You are now the symbol of

the nation”.

Then as rehearsed earlier with Kaunda, Mutembo

made his demands for independence to the governor.

Oddly, Mutembo was made to swear on a bible and

was then taken to the Governor’s palace for four days.

He was then driven a few miles away to a house at 6

Nalikwanda Drive, where he spent the next few

months, guarded by police, but with a full set of

servants to take care of him.

In March 1964, Mutembo was taken to a town

called Abercorn, since renamed to Mbala, and given a

plot of land to live on at 214, Bwangalo Road, and

awarded a lifetime pension. He stayed there until

October 17, 1964 when he was flown back to Lusaka

and reunited with Kaunda. Zambia got its

independence on October 24th, 1964 with Mutembo

attending the ceremony and standing only a few feet

from Kaunda and the British representative, Princess

Mary (officially, Mary, Princess Royal and Countess

of Harewood).

On October 23, 1974, a statue based off

photographs of Mutembo when he broke his chains

was unveiled. It has since become the symbol of

Zambia’s fight for independence from colonial rule.

Many memorials take place for fallen freedom fighters

at this statue, and it has been placed on the countries

banknotes. Meanwhile, Mutembo donated his land in

Mbala to the United Nationalist Independent Party

(UNIP) which used it for a while, but it was later

turned into a carpentry business. His pension and

status also disappeared when Kaunda ceded power in

1991, and today few remember Mutembo’s name or

role in their independence.

Mutembo was last known as still working to

regain his status and pension returned to him but has

made no progress with the current government.

Several articles have been written about him in the

local press, yet most are reported as not knowing the

name of the man whom the statue was made of. The

statue lives on in modern memory, while the man

slowly fades away.

There are several things about this story that leave

me scratching my head. Most of it is due to the

vagueness of the stories available online and in print,

and have me asking, “Is this story true?”

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

391

It seems really odd that the Colonial Governor

would declare Mutembo to be the symbol of the new

country. Yet, once we know that the Governor was to

assist in the peaceful transition of power, perhaps it

isn’t as odd as it first would seem. The manner in

which it was reportedly played out, however, is

nothing but strange.

In looking at why would they chain Mutembo in

the first place leaves us wondering why, if a person

was going to be executed, would they need to chain

him instead of tying him down, or simply just shoot

him? Further, why tell him to break the chain, which

would normally be shear folly? Taunting a prisoner

isn’t unheard of, but it usually isn’t while a room is full

of supposed reporters. While I’m certainly not

speaking from experience here, it doesn’t make sense

that if you want to kill someone, you offer them an out,

and then honor it. It reads like a cheesy novel, having

a man bent on killing someone be honor bound by his

word. A logical conclusion is that it must’ve all been

planned, and that the police were goading Mutembo to

try to break the chain in order to make him do so for

the reporters.

When we examine Mutembo’s motives, and his

mission, it is not beyond suspicion that he was in

collusion with Kaunda, and perhaps even Governor

Hone, all along to create a national symbol for the

budding independence of Zambia. While I cannot state

for certain that the story, including the chain breaking,

is sprinkled with some untruth or deception, I can’t

help being suspicious concerning the lack of specified

dates and timelines, and certain odd behavior,

especially by the governor after the chain breaking.

My take on this is that Kaunda and his cabinet had

decided to fool Mutembo into thinking that he had

been chosen to be a martyr for his country, all the

while knowing that he would try to pull the chains,

which must’ve been carefully altered to make them

breakable. By his own accounts, Mutembo stated that

he tried very hard, and kept on trying, eventually

snapping the chain, to the supposed surprise of all in

attendance. To continue the farce, perhaps he was

made to swear on the bible that he had done so, which

would further cement his conviction that it was real.

It seems that he was then held for quite a while,

away from all who would be able to convince him that

the chain may have been weakened somehow. His

sequestration at this point seems to be something that

wasn’t necessary unless they were trying to keep

others from interfering in some type of odd con job.

Later, he was then given acreage to live on far from

the capital, and from those whom he would have had

close relationships with. The distance by road between

Lusaka and Mbala in 2018 is listed as 636 Miles, or

1024 Kilometers, with an estimated travel time of 14

hours. I’m quite certain it would have taken longer in

the 1960’s. It seems odd that the ‘Symbol of the

Country” would be placed so far away from those he

had worked so closely with, and far from the goings

on of a new nation.

Of all the stories I’ve read, most are identical in

their chronology, but a bit vague on certain dates. Most

suspiciously, while there are many photos of the chain

breaker statue, and of Mutembo, there are none to be

found of Mutembo breaking the chains in the police

headquarters office where he was supposedly about to

be executed unless he broke the chains. If the statue

was based off photos, wouldn’t those photos

themselves also be famous?

But supposing that the story of breaking the chain

is fake, and Mutembo was either fooled or was a

willing participant, there is still the question of why it

would be done. Would it matter if it was merely an

allegorical representation, instead of a real man? In

order to push a spirit of unification among the

populace, perhaps having a real person embody the

strength of the resolve for independence was thought

to be a quicker way to unite the people than a statue

that merely represents a concept of independent rule

without a personal connection. After all, there are 73

distinct indigenous ethnic groups within the Zambian

border. The statue depicting a man breaking the chains

of colonial oppression serves its purpose to embolden

the people with the strength of national unity and

pride. But as a statue of a real man, now mostly

forgotten, it serves as a proxy for each of each

Zambian citizen’s personal break from foreign rule.

Whether it is accepted as told, and we ignore the

apparent holes in the story as evidence for a faked

sequence of events, or draw the conclusion that the

whole scene was scripted and sold to the Zambian

public, is there any real impact or is it rather a moot

point at this time? I am reminded that in the United

States there is a story of a young George Washington

cutting down a cherry tree and, when confronted, was

so honest that he admitted that he was the one who

committed the deed. The story was made famous after

Washington’s death on December 14th, 1799, by

Parson Weems in his book The Life of Washington,

first printed in 1800 and reprinted in 1809. Parson

Weems claimed that he heard the story from an old,

unnamed neighbor who claimed to have known

George Washington when he was a small child. As the

only reference to the story, it can hardly be accepted

as a credible source. True or not, the story itself does

no harm, and as it’s been repeated it so often, it resides

deep within the hearts and minds of almost every

American. Whatever the role that Mutembo and the

other’s played, Zambia was able to achieve its

independence without the violence and bloodshed that

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

392

so many others have had to endure. Surely that is

worth any doubt concerning a man who broke a chain

to free himself yet wound up binding the people of

Zambia together as a nation.

Zambian Banknote issued 1989

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * Nov/Dec 2018 * Whole No. 318_____________________________________________________________

393

Lyn Knight Currency Auct ions

If you are buying notes...

You’ll find a spectacular selection of rare and unusual currency offered for

sale in each and every auction presented by Lyn Knight Currency

Auctions. Our auctions are conducted throughout the year on a quarterly

basis and each auction is supported by a beautiful “grand format” catalog,

featuring lavish descriptions and high quality photography of the lots.

Annual Catalog Subscription (4 catalogs) $50

Call today to order your subscription!

800-243-5211

If you are selling notes...

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions has handled virtually every great United

States currency rarity. We can sell all of your notes! Colonial Currency...

Obsolete Currency... Fractional Currency... Encased Postage... Confederate

Currency... United States Large and Small Size Currency... National Bank

Notes... Error Notes... Military Payment Certificates (MPC)... as well as

Canadian Bank Notes and scarce Foreign Bank Notes. We offer:

Great Commission Rates

Cash Advances

Expert Cataloging

Beautiful Catalogs

Call or send your notes today!

If your collection warrants, we will be happy to travel to your

location and review your notes.

800-243-5211

Mail notes to:

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions

P.O. Box 7364, Overland Park, KS 66207-0364

We strongly recommend that you send your material via USPS Registered Mail insured for its

full value. Prior to mailing material, please make a complete listing, including photocopies of

the note(s), for your records. We will acknowledge receipt of your material upon its arrival.

If you have a question about currency, call Lyn Knight.

He looks forward to assisting you.

800-243-5211 - 913-338-3779 - Fax 913-338-4754

Email: lyn@lynknight.com - support@lynknight.c om

Whether you’re buying or selling, visit our website: www.lynknight.com

Fr. 379a $1,000 1890 T.N.

Grand Watermelon

Sold for

$1,092,500

Fr. 183c $500 1863 L.T.

Sold for

$621,000

Fr. 328 $50 1880 S.C.

Sold for

$287,500

Lyn Knight

Currency Auctions

Deal with the

Leading Auction

Company in United

States Currency

Anatomy of a Series:

Plate Numbers on Series 2009 $10 Federal Reserve Notes

By Joe Farrenkopf

Plate development of Series 2009 $10 Federal

Reserve Notes bearing the signatures of Secretary

of the Treasury Timothy F. Geithner and Treasurer

of the United States Rosa Gumataotao Rios began in

March 2010, and printing of the first sheets from

those new series plates began five months later at

the Western Currency Facility (WCF) in Fort Worth,

Texas. Except for two hiatuses of several months

each, production of Series 2009 $10 FRNs continued

at the WCF through October 2013 when the last run

of notes from the JG‐B block was serialed. In all,

1,465,600,000 regular notes were serialed for all

twelve Federal Reserve districts, and 7,936,000 star

notes were serialed for four1 Federal Reserve

districts. The quantity of both regular and star notes

combined was about 4% less than the preceding

Series 2006.

The WCF has twelve presses for printing faces

and backs of currency sheets. Four of those presses

are the newer Super Orlof Intaglio (SOI) presses,

which use three plates in rotation, while the

remaining eight presses are the older I‐10 presses,

which use four plates in rotation. That means that

four sheets are printed, one from each plate, before

the first plate makes its second impression. All

Series 2009 $10 FRNs were printed using the I‐10

presses.

The lifespan of a currency printing plate can

vary widely from one plate to another. For instance,

a plate could sustain damage that warrants removal

from the press after little use; nowadays, such

plates are not usually repaired and reintroduced

into production. But barring any mishaps, it is

common for a plate to make hundreds of thousands

of impressions before wearing out. Some plates

that are particularly durable and happen to remain

damage‐free can exceed easily one million

impressions. If a set of four plates remains usable

for 500,000 impressions, those plates collectively

will print 2,000,000 sheets. A standard press run of

regular $1, $2, $5, $10 and $20 notes comprises

200,000 sheets, so those four plates would produce

enough sheets to serial as many as 10 press runs

(not taking into account spoilage for any

defective/damaged sheets).

1 The BEP’s monthly production report from

September 2010 listed a full (3.2 million) note‐