Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

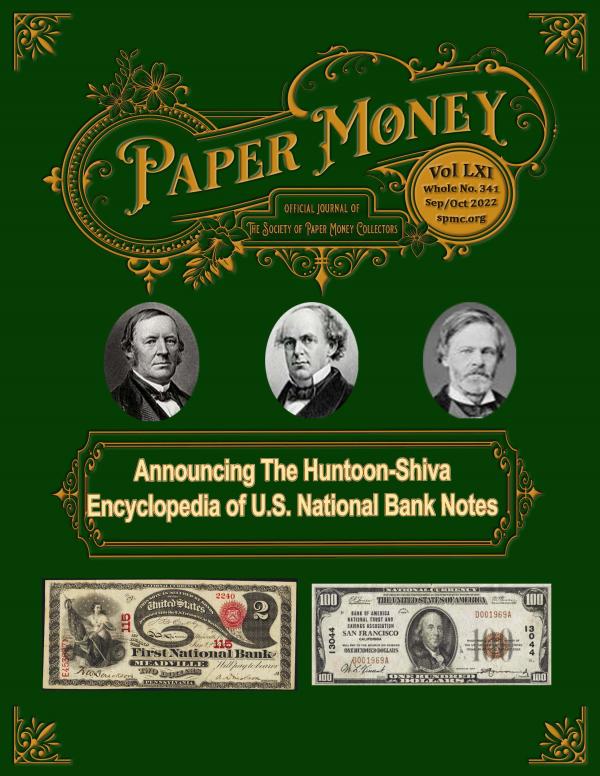

Introduction to the Huntoon-Shiva Encyclopedia of U. S. National Bank Notes

In the Beginning--Wendell Wolka

Origin of Type 2 Numbers--Peter Huntoon

Ransom At the Border--Lee Lofthus

Unreported Nebraska NBN--Matt Hansen

1862 $ 63 Legal Type Classification Chart Revised--Peter Huntoon

Southern Printers-Pt. 2--Charles Derby

Not Just About Vignettes--Tony Chibbaro

Fractional Currency Wallet--Rick Melamed

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

Announcing The Huntoon-Shiva

Encyclopedia of U.S. National Bank Notes

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

1550 Scenic Avenue, Suite 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 • 800.458.4646 • 949.253.0916

470 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10022 • 800.566.2580 • 212.582.2580

1735 Market Street, Suite 130, Philadelphia, PA 19103 • 800.840.1913 • Philly@StacksBowers.com

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • Philadelphia • New Hampshire • Oklahoma • Hong Kong • Paris

SBG PM Nov22Consign PR 220801

Stack’s Bowers Galleries Currency

Continues to Break Records

Consign now to the November 2022 Baltimore Showcase Auction

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Auction: November 1-4 & 7-10, 2022 • Costa Mesa, CA

West Coast: 800.458.4646 • East Coast: 800.566.2580 • Consign@StacksBowers.com

Fr. 260. 1886 $5 Silver Certificate. PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Estimate: $30,000-$40,000 – Realized $50,400

Fr. 355. 1890 $2 Treasury Note. PMG Gem Uncirculated 66 EPQ.

Estimate: $50,000-$75,000 – Realized $93,000

Fr. 375. 1891 $20 Treasury Note. PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Estimate $12,500-$17,500 – Realized $20,400

Fr. 1200am. 1922 $50 Gold Certificate Mule Note.

PMG Choice Uncirculated 64.

Estimate $8,000-$12,000 – Realized $24,000

Fr. 2200-Idgs. 1928 $500 Federal Reserve Note.

Minneapolis. PMG Choice Uncirculated 64 EPQ.

Estimate $15,000-$25,000 – Realized $31,200

Fr. 2407. 1928 $500 Gold Certificate.

PMG Choice Very Fine 35 EPQ.

Estimate $15,000-$25,000 – Realized $19,200

T-3. Confederate Currency. 1861 $100. PMG Choice Uncirculated 63.

Estimate: $30,000-$50,000 – Realized $36,000

Fr. 2211-Glgs. 1934 $1000 Federal Reserve Note. Chicago.

PMG Gem Uncirculated 65 EPQ.

Estimate $15,000-$25,000 – Realized: $36,000

312

Introduction to the Huntoon-Shiva Encyclopedia

In the Beginning--Wendell Wolka

Origin of Type 2 Numbers--Peter Huntoon

Unreported Nebraska NBN--Matt Hansen

Ransom At the Border--Lee Lofthus

335

310

315

330

349 Southern Printers-Keating & Ball-Pt. 2--Charles Derby

359 Not Just About Vignettes--Tony Chibbaro

370 Fractional Currency Wallet--Rick Melamed

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

305

1862 & 63 Legal Type Classification Chart-Rebised--Peter Huntoon 338

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Doug Ball

Hank Bieciuk

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Forrest Daniel

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Clifford Mishler

Judith Murphy

Dean Oakes

Chuck O’Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

Herb & Martha

Schingoethe

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

From Your President

Editor Sez

New Members

Quartermaster

Uncoupled

Cherry Picker

Obsolete Corner

Small Notes

Chump Change

Robert Vandevender 307

Benny Bolin 308

Frank Clark 309

Michael McNeil 362

Joe Boling & Fred Schwan 365

Robert Calderman 372

Robert Gill 374

Jamie Yakes 376

Loren Gatch 378

Stacks Bowers Galleries IF C

Pierre Fricke 305

Higgins Museum 328

Bob Laub 328

Lyn Knight 329

Tampa Paper Expo 337

PCGS-C 348

Evangelisti 358

Tom Denly 358

Tony Chibbaro 361

Fred Bart 377

FCCB 377

ANA 379

PCDA IBC

Heritage Auctions OBC

Fred Schwan

Neil Shafer

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

306

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT Robert Vandevender II

rvpaperman@aol.com

VICE-PRES/SEC'Y Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Robert Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

Mark Anderson mbamba@aol.com

Robert Calderman gacoins@earthlink.net

Gary Dobbins g.dobbins@sbcglobal.net

Matt Drais stockpicker12@aol.com

Mark Drengson markd@step1software.com

Pierre Fricke

aaaaaaaaaaaapierrefricke@buyvintagemoney.com

Loren Gatch lgatch@uco.edu

William Litt Billlitt@aol.com

J. Fred Maples

Cody Regennitter cody.regennitter@gmail.com

Wendell Wolka

APPOINTEES

PUBLISHER-EDITOR

Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Wendell Wolka purduenut@aol.com

LEGAL COUNSEL

Megan Reginnitter mreginnitter@iowafirm.com

LIBRAIAN

Jeff Brueggeman

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark frank_clark@yahoo.com

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Shawn Hewitt

WISMER BOOk PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Robert Vandevender IIFrom Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

maplesf@comcast.net

purduenut@aol.com

jeff@actioncurrency.com

In June, we were very sad to learn of the passing of our Hall of Fame

Member Don C. Kelly. As most of you know, Don was a big part of our

hobby and made significant contributions in research and literary

works. No doubt many of you have notes in your collections that at

one time were in a case owned by Don. He will be missed.

Recently, I read an article regarding changes in English currency.

With those of you owning a wallet full of “paper” Bank of England £20

and £50 banknotes, I trust that by now you have exchanged them for

the new polymer notes as the legal tender status will be withdrawn at

the end of September. I must admit, the new £50 polymer note

featuring the computer scientist Alan Turing is a sharp looking note.

I have fantastic news to report. Peter Huntoon and Andrew Shiva have

worked hard over several years to create the new “Huntoon-Shiva

Encyclopedia of U.S. National Bank Notes.” I am pleased to announce

that this work will be jointly published by the National Currency

Foundation and the Society of Paper Money Collectors and available to

our members via a link from the SPMC website and our SPMC Wiki

Page. Please check it out.

In addition to the Huntoon-Shiva Encyclopedia, we have several new

data-related resources in the works and will be rolling them out to the

membership and the public in the upcoming months so stay tuned.

Some of these upcoming items will be available free to the public while

others will be restricted to our membership. Please keep an eye out for

announcements in upcoming issues of Paper Money.

In July, I made a visit to the Summer FUN show in Orlando. Although

the “Summer in Florida” show isn’t quite as large as the Winter FUN

show in January, it appeared to have a very good turnout. After

dropping off a stack of notes to a third-party grading service in hopes

of the grades being returned with favorable results, I walked the floor

and was happy to meet with several of our members and friends.

During our August routine SPMC Board of Governors meeting, I was

happy to welcome our two newest board members, Jerry Fochtman and

Andy Timmerman to our group. I am looking forward to their

contributions to the Board.

Planning for our annual meeting at the Winter FUN is continuing

and looking good. We will be providing more details on the SPMC

website shortly. Make plans on attending. I hope to see many of you

there in January.

307

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY (USPS 00‐

3162) every other month beginning in January. Periodical

postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055, Gainesville,

GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2020. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or part

without written approval is prohibited. Individual copies of this

issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the secretary for $8

postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries concerning non ‐

delivery and requests for additional copies of this issue to

the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the editor. Accepted

manuscripts will be published as soon as possible, however

publication in a specific issue cannot be guaranteed. Opinions

expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of the

SPMC. Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of the author

to the editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good faith”

basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases where

special artwork or additional production is required, the

advertiser will be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are

not commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not

endorse any company, dealer, or auction house. Advertising

Deadline: Subject to space availability, copy must be received

by the editor no later than the first day of the month

preceding the cover date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the

March/April issue). Camera‐ready art or electronic ads in pdf

format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

Required file submission format is composite PDF v1.3

(Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted files should

conform to ISO 15930‐1: 2001 PDF/X‐1a file format standard.

Non‐ standard, application, or native file formats are not

acceptable. Page size: must conform to specified publication

trim size. Page bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond

trim for page head, foot, and front. Safety margin: type and

other non‐bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”.

Advertising c o p y shall be restricted to paper currency, allied

numismatic material, publications, and related accessories.

The SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject objectionable

or inappropriate material or edit copy. The SPMC

assumes no financial responsibility for typographical

errors in ads but agrees to reprint that portion of an ad in

which a typographical error occurs.

Benny

Space

Full color covers

1 Time

$1500

3 Times

$2600

6 Times

$4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half‐page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter‐page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth‐page B&W 45 125 225

Dog Days Were Dogged This Year

Yes, in Big D, we were fortunate enough to not break the

record for the hottest summer of record, just made it to #2!

Over 40 days of over 100 days and all 31 days in July were over

100. We are now seeing some respite with lower temps (98 or

so) and some rain. Soon it will be over! the whole country

seems to have crazy weather this summer. Hope you all stayed

safe.

Summer shows seemed to be a hit. I unfortunately was not

able to attend any but reports were that Summer FUN, ANA,

BRNA, etc were all good shows and the public is coming back

with a vengeance. The only downsides I have heard are some

lack of material and “optimistic” pricing. But it is good to get

back to the show circuit to see old friends, make new

acquaintances and overall enjoy the commaraderie that shows

bring. I hope you all will make plans now to attend the FUN

’23 in early January. The SPMC will be having our normal

IPMS activities of old, including the breakfast, Tom Bain raffle

and award presentations.

Speaking of awards, please go to the SPMC website,

SPMC.org and vote on the literary awards and reward our fine

authors for their diligence and hard work.

This is a very special issue of PM. It introduces the Shiva-

Huntoon Encyclopedia of U. S. National Bank Notes. This is a

monumental work that will benefit collectors for years to

come. This encyclopedia covers every aspect of U.S. national

bank notes issued from 1863 to 1935. It contains over 1,500

pages in 144 chapters, and is designed to be a dynamic work in

progress. It is truly a monumental work and is enjoyable and

informative for all paper collectors, not just those into

nationals. I only have one national--a South Carolina to go

with my collection of that state and I really enjoyed going

through this work. No, it did not convert this fractional guy to

nationals but, well, maybe..... The SPMC thanks Peter and

Andrew for allowing us to be a part of this project. It is simply

incredible. There is a link to the book on the website. Go to it

and enjoy.

308

The Society of Paper Money

Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit

organization under the laws of the

District of Columbia. It is

affiliated with the ANA. The

Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the International

Paper Money Show. Information

about the SPMC, including the

by-laws and activities can be

found at our website--

www.spmc.org. The SPMC does

not does not endorse any dealer,

company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and

LIFE. Applicants must be at least 18

years of age and of good moral

character. Members of the ANA or

other recognized numismatic

societies are eligible for membership.

Other applicants should be sponsored

by an SPMC member or provide

suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR.

Applicants for Junior membership

must be from 12 to 17 years of age

and of good moral character. A parent

or guardian must sign their

application. Junior membership

numbers will be preceded by the letter

“j” which will be removed upon

notification to the secretary that the

member has reached 18 years of age.

Junior members are not eligible to

hold office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues

for members in Canada and Mexico

are $45. Dues for members in all

other countries are $60. Life

membership—payable in installments

within one year is $800 for U.S.; $900

for Canada and Mexico and $1000

for all other countries. The Society

no longer issues annual membership

cards but paid up members may

request one from the membership

director with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who

joined the Society prior to January

2010 are on a calendar year basis

with renewals due each December.

Memberships for those who joined

since January 2010 are on an annual

basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due

before the expiration date, which can

be found on the label of Paper

Money. Renewals may be done via

the Society website www.spmc.org

or by check/money order sent to the

secretary.

WELCOME TO OUR

NEW MEMBERS!

BY FRANK CLARK

SPMC MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

NEW MEMBERS 07/05/2022

15445 Nick Hamze, Website

15446 Cody Quintana, Website

15447 Larry Schuffman, Frank Clark

15448 Justin McClureWebsite

15449 Bob Pearson, Frank Clark

15450 Lyndra Spor, Website

15451 William Ripley, Website

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

NEW MEMBERS 08/05/2022

15452 Joseph Smith, Website

15453 Bryan Harrison, Don Kelly

15454 Clifford Cooper, Website

15455 Robert Anderson, Frank Clark

15456 Mark Borckardt, Website

15457 Douglas Doonan, Website

15458 Ronald Pettie, Website

15459 Bob Reed, Robert Calderman

15460 Jonathan Kukk, ANA Ad

15461 Robert Laird, Whitman Pub.

15462 Stan Clark, Website

15463 Josh Colon, Website

15464 John Salviani, Robert Calderman

15465 David Dixon, Website

15466 Ray Oshinski, Website

15467 Mark Ellingson, Website

15468 Timothy Anderson, Rbt Calderman

15469 Bryan Kastleman, ANA Ad

15470 Josephine Ellsworth, Webiste

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

Dues Remittal Process

Send dues directly to

Robert Moon

SPMC Treasurer

104 Chipping Ct

Greenwood, SC 29649

Refer to your mailing label for when

your dues are due.

You may also pay your dues online at

www.spmc.org.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

309

The Huntoon-Shiva Encyclopedia of U. S. National Bank Notes

It is with excitement that Andrew Shiva announces the release of the Encyclopedia of U. S. National

Bank Notes published jointly by his National Currency Foundation and the Society of Paper Money

Collectors.

The encyclopedia is huge, currently containing some 1,500 pages, 1,400 illustrations and 210 tables

divided into 144 chapters organized into 17 topical sections.

The encyclopedia is too large and would be too costly to publish in print form so it is being made

available in digital form through both the National Currency Foundation and Society of Paper Money

websites.

Both the NCF and SPMC have educational commitments to disseminate information that promotes

the research and collecting of paper money; thus, publication of the encyclopedia affords a natural

collaboration that furthers this objective for both organizations. Preparation of the encyclopedia has been

largely sponsored by the NCF and details of maintaining it on line have been assumed by the SPMC. It is

presented free of charge as a service to not only numismatists but the public at large.

The encyclopedia covers every aspect of national bank notes from why they originated during the

Civil war to why they were phased out 72 years later. As for the notes themselves, an explanation is

provided for why there were different series and backs. The protocols are explained that governed how

every other design element on the notes functioned and evolved over time. Much of this was dictated by

Congressional legislation, the rest by decisions made by Treasury officials as the national bank note era

unfolded.

The encyclopedia represents a significant part of the life work of U. S. currency researcher Peter

Huntoon, who has been writing about national bank notes since 1966. Over the intervening decades, he has

collaborated with the leading national bank note researchers and collectors to coauthor this treatise.

The core of most of the encyclopedia represents original research that Huntoon and his colleagues

have conducted using primary Treasury documents now preserved in the National Archives and at the

Bureau of Engraving and Printing. A major resource that they used were the certified proofs lifted from the

printing plates that were used to print national bank notes now housed in the National Numismatic

Collection in the Smithsonian Institution.

A significant fraction of the information in the encyclopedia builds on material already published

elsewhere, primarily in the SPMC journal Paper Money. However, much has never been released before.

All of it has been reworked, updated and corrected based on the most recent research available. One major

value of the encyclopedia is that it conveniently assembles all of this material in one place.

The arrangement of the subject matter into chapters within topical sections allows for the addition

of new chapters as they are written. Equally significant is that by making it available digitally, updates and

corrections can be made in real time as new information and insights are developed and mistakes—even

typos— are discovered. To this end, a version date is provided at the bottom of the first page of each chapter.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

310

The encyclopedia is designed to be a dynamic work in progress.

This link will take you to the encyclopedia.

https://content.spmc.org/wiki/Encyclopedia_of_U.S._National_Bank_Notes

Click on “Search the Table of Contents, read or download chapters”

Click on any chapter of interest to read or down load it.

A few chapters have internal hot links to large tables or photo files.

A link can also be found on the SPMC.org website page.

Original series

Series 1875

Series 1882

Brown Back

1902 Red Seal

1929 Small

Size

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

311

In The Beginning….

by Wendell Wolka

Most collectors have a fairly vague idea of how National Bank Notes came into being. The nation was at war,

needed to develop a stable national approach to banks of issue and set up national banks to replace the existing state

banks of issue that had served the nation’s needs since independence. End of story; nothing else to see here; move

along.

With a bit more digging, and a chance encounter with research done by Richard T. Erb some fifty years ago, the

story is far more intriguing and interesting than one might imagine. For starters, the federal legislation that ultimately

became known as the National Bank Act, whose foundations have traditionally been attributed to the 1838 New York

banking legislation, was, in fact, heavily influenced by the 1845 Ohio banking legislation that created the State Bank

of Ohio and the state’s so-called “Independent Banks.”

But first, let’s pick up the story in late 1861…

By then it had become obvious that the Civil War was not going to be a short war and was not going to be an

inexpensive war either. Secretary of the Treasury Salmon Chase, former Governor and United States Senator from

Ohio was faced with the prospect of needing to sell ever increasing amounts of bonds to

keep the war effort moving forward. Continuing Union defeats on the battlefield had not

helped this effort at all and Chase finally came up with a concept to address the issues. He

would create a class of “national banks” whose circulation would be secured wholly by

United States Bonds. This would create a huge new market for the sale of bonds. As an

added benefit, these bonds could be paid for with the new federal “greenbacks” which

would help keep a lid on the amount of currency in circulation and therefore inflation. The

concept of using common designs for each denomination for all national bank notes was

also factored into Chase’s thinking. His experience with Ohio banks during his terms as

Governor and Senator was that common or very similar designs were used for all branches

of the State Bank of Ohio and for the other Ohio state-chartered banks of issue as well.

Once the basic planks of the plan were in place, Chase went looking for a salesman for the plan in the halls of

Congress. His first choice was Representative Elbridge G. Spaulding of New York. Spaulding had spearheaded the

drive to create Legal Tender notes in 1862 and also wrote up a bill to create national banks

but soon abandoned his support for the latter, feeling that simply issuing more Legal

Tender notes to fund the war effort was more expedient. Chase then turned to

Congressman Samuel Hooper of Massachusetts who was ineffectual in two efforts to get

the bill through the House Ways and Means Committee during the course of 1862-63.

Chase now enlisted another Ohioan, Senator John Sherman, brother of highly regarded

Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, who rammed the 1863 national bank

legislation through the Senate. The bill made it through the House Ways and Means

Committee and passed on a subsequent floor vote. President Lincoln signed the bill into

law on February 25, 1863. Why was the third time the charm? The staggering Union

Most of the national bank legislation of

1863 found its roots in the 1845 Ohio

legislation creating the State Bank of Ohio

and other state banks. All of the branches

issuing this denomination in the 1850s-60s

shared a common design. Most branches

became national banks beginning in 1863.

Salmon Chase

John Sherman

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

312

defeat at Fredericksburg in mid-December, 1862 had provided vivid proof that the war was going to be a long one

and Chase made it very clear to all who would listen that the financial situation faced by the Treasury Department

could ultimately lead to defeat if the national bank legislation was not passed. In short, a no vote would be courting

national disaster.

The antebellum New York banking legislation has usually been given credit for being the source of the banking

principles embraced by this new legislation. But research done in 1973 by Richard T. Erb, Acting Deputy Comptroller

and Licensing Manager in the Comptroller of the Currency’s Office, substantially rebuts that claim. Erb made side-

by-side comparisons between the New York, Ohio, and federal legislation and came to a clear conclusion. By in

large, the federal law was largely based on the 1845 Ohio legislation that created the State Bank of Ohio branch

network and the state’s Independent Banks.

The federal legislation contained 43 sections. Of these, seventeen sections are not even mentioned or addressed

in the New York legislation while only six sections from that legislation are included verbatim. Their inclusion was

probably the handiwork of Representative Spaulding when he produced a first draft of a national bank bill in 1862 as

Spaulding served as New York State Treasurer for a year before the war. By contrast, 22 sections from Ohio’s 1845

Banking Law were included in the federal legislation verbatim and another seven sections, only found in the Ohio

legislation, were also included covering the same areas in the same manner. In aggregate, 67% of the 1863 national

banking legislation is clearly of Ohio origin while only 14% can be tied to New York law. Given the Ohio

backgrounds of both Chase and Sherman, this should probably not be much of a surprise.

Another Midwesterner, Hugh McCulloch, was drafted by Chase to serve as the first Comptroller of the Currency

and tasked with turning the legislation into action. McCulloch was a well-respected banker from Indiana who had

served with distinction with the State Bank of Indiana and as President of the Bank of

the State of Indiana; two of the strongest bank networks in the nation. Ironically

McCulloch had come to Washington in 1862 to lobby against the new national banking

legislation, representing the Bank of the State of Indiana. His opposition was based on

the fact that the new federal law would effectively drive state banks of issue out of

business (which was essentially true.) McCulloch was not offered the Comptroller of

the Currency position until after the passage of the new 1863 national banking law, but

once in office, was unwavering and tireless in his efforts to get banks on board with the

National Bank concept.

McCulloch found the initial reception to this new class of banks by the nation’s existing commercial banks to

be “underwhelming.” While western and middle state banks tended to be more open to converting to national banks,

the same could not be said for money center banks in the east. For example, after chartering three national banks in

New York City, it would be until February, 1864 before any more came on board. As McCulloch mentions in his

memoirs, Men and Measures of Half A Century, there were four common reasons for the hesitancy of many bankers.

The new system was something completely different than anything that had been done before.

Therefore, the chances of success or failure were an unknown.

Because United States bonds were to be the sole source of security for national bank circulations, the

banks would be ruined if the Union lost the war. This was a legitimate concern in early 1863, before the

victories at Vicksburg and Gettysburg solidified Union prospects, and, of course, is exactly what happened

to Southern Banks in 1865.

Hugh McCulloch (right) appeared on

$100 issues of the Bank of the State of

Indiana, most of whose branches

became national banks.

Hugh McCulloch

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

313

National Banks would likely be exposed to increased federal oversight and regulations.

Banks would be required to change their names.

This was a showstopper with a large number of state banks who had worked for years to make their

name a strong and recognizable brand and marketing tool. Chase’s original intent was to simply number all

of the national banks in any given location based on when their charter numbers were assigned. So, if there

were four applying banks in, say, Evansville, IN, the banks would be titled as the First, Second, Third, and

Fourth National Banks of Evansville. Not many bankers, particularly in big cities, wanted to go from maybe

The Bank of the Republic to The Eleventh National Bank.

Hugh McCulloch used his background as a well-known and nationally respected state bank officer to his

advantage in addressing these concerns. Responding to the first concern, he told wary bankers that the probability of

success for national banks was quite high because the capital to start each national bank was real and actually paid

in unlike many state banks. The security for each national bank comprised solely United States bonds with a 10%

margin and notes of any failed national banks would be promptly redeemed by the United States Treasury. Finally,

all national banks would be regularly audited.

Next McCulloch reminded prospective bankers that if the Union lost the war, it would not make any difference

what bonds were being held to secure their circulations. The banks’ futures were tied to the Union cause whether they

were state or national banks. Most bankers had to agree with this pragmatic observation.

McCulloch argued that federal regulation would probably not be significantly greater or different than most

banks were dealing with on the state level by 1863 and his Indiana banking experience gave credibility to his

observation. He also pointed out that national banks, as a class of bank that encompassed the entire nation, would

surely have more lobbying impact in Washington than they had as individual state banks.

The final sticking point required all of McCulloch’s persuasive skills to resolve. Chase was initially adamant

that the banks would be numbered as described above. After an extended bit of wrangling, McCulloch finally got

Chase to agree to a compromise whereby the word National had to appear someplace in the bank title. So, for

example, the Bank of Commerce could become the National Bank of Commerce or the Merchants and Planters Bank

could take the name Merchants and Planters National Bank. The sole exception to this was the Bank of North America

in Philadelphia. Because of its stature as the first bank chartered in the United States by Congress in 1781, it was

allowed to become a national bank without changing its name or adding National to its title. The bank’s officers had

argued that the bank’s name was granted by Congress as part of the original charter and should therefore be

grandfathered in.

Even with all of McCulloch’s handholding and reasoning, things were still a slow go in terms of conversions,

and in early 1865, Congress provided the coup de grace by adding a provision to the Amendatory Act of March 3,

1865 (Section 6) which stated:

“And be it further enacted, That every national banking association, State bank, or state banking association,

shall pay a tax of ten per centum on the amount of notes of any person, State bank, or State banking association, used

for circulation and paid out by them after the first day of August, eighteen hundred and sixty-six and such tax shall

be assessed and paid in such manner as shall be prescribed by the Commissioner of Internal Revenue.”

This 10% tax, which was part of the federal tax revenue rather than bank legislation, was the stick that finally

got the foot-draggers moving since it essentially wiped out the profitability of issuing state bank notes. There were

all sorts of other taxes levied on banks, but this was the crowning blow that brought the era of note-issuing state banks

to a close. Interestingly, it appears that this provision has never been repealed.

So, there you have it. America’s national banks, still prevalent on the American scene even today, improbably

owe their existence to three men from the Midwest; Salmon Chase, John Sherman, and Hugh McCulloch. Gentlemen,

we salute you for a job well done!

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

314

Serial Numbering the Series of 1929

National Bank Notes &

Origin of Type 2 Numbers

PURPOSE

This chapter will explain how the Series of 1929 national bank notes were serial numbered and

why the numbering system was changed to the type 2 variety in 1933.

It is appropriate to explain the special cases when B suffix letters were used on type 1 sheets, and

when B prefix letters were used on type 2 notes in this chapter.

Two situations found in the issuance data for the individual banks are explained; specifically, the

shipment of partial sheets and gaps in the serial number sequences.

SERIAL NUMBERING

Series of 1929 national bank notes were serial numbered and sealed in 6-subject sheet form. Two

distinctly different serial numbering systems were used on the Series of 1929. The first, called type 1,

involved sheet numbers wherein all the notes bore the same number. The numbers had a suffix letter, and

the prefix varied from A to F depending on the position of the note on the 6-subject sheet.

The type 2 serials were note numbers ordered consecutively down the sheet with a prefix, but no

suffix letter. In addition, a brown charter number was overprinted next to each serial number adjacent to

the central portrait.

Three serial numbering conventions were common to both the type 1 and 2 issues. Serial numbering

started at 1 for each different denomination for each bank. Serial numbering started over when bank titles

were changed. However, serial numbering did not start over when bank signatures changed.

The delivery of uncut sheets to bankers was an established tradition dating from long before the

Bureau of Engraving and Printing came into existence. Sheets were convenient when bankers had to hand

sign their notes, but that convenience vanished once the signatures were printed.

A second inherited tradition was that of using the same serial number on all the notes on a given

sheet. Different plate letters were used to distinguish between like subjects on the sheet.

Sheet numbering of national bank notes originated with the bank note companies in 1863 and was

passed forward to the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in 1875. The tradition of issuing the notes in sheet

form and using the same serials on all the subjects on a sheet was carried forward during the conversion to

small size Series of 1929 type 1 nationals, but with a small twist.

Figure 1. A note from the last sheet of $10s issued by the bank that was

obviously saved by a banker.

The Paper

Column

Peter Huntoon

Lee Lofthus

James Simek

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

315

The source for the 6-subject sheets

was 12-subject plates whereon the subjects

were lettered A through L. Once the sheets

were cut in half, the G through L plate letters

on right halves served no purpose. Instead,

prefix letters A through F in the serial

numbers were used to indicate the position

of the notes on the half sheets regardless of

which half of the 12-subject sheet was being

numbered. The plate letters were ignored.

This is a wonderful example of

human inertia. Everyone simply kept

moving in the same direction, creating

whatever convolution was necessary to stay

the course.

The problem with adopting the type

1 sheet serial numbering style was that those

who handled and issued the sheets found

themselves locked into an archaic format

that quickly forced them to do their

accounting in units of six notes, instead of

individual notes.

Initially, in 1929, the Comptroller’s

clerks would receive notification from the

National Bank Redemption Agency that

some dollar amount of notes had been

redeemed for a given bank, and the clerks

would issue notes, which commonly

involved cutting notes from the sheets to

make up the correct total. This led to

cumbersome entries in the ledgers and

greatly complicated the rectification of the

accounts.

In short order, the Comptroller

requested that the National Bank

Redemption Agency certify redemptions in

6-note multiples so that the Comptroller’s

office could issue whole sheets to the banks.

This complicated the bookkeeping in the

Redemption Agency, which added to their

costs and forced them to hold odd numbers

of notes for varying periods at the expense

of expeditiously processing the all the notes

on behalf of the issuing banks.

Figure 2. Type 1 sheet where the serial

numbers are sheet numbers. Notice that all

the notes have the same serial number, and

their positions in the sheet are revealed by the

prefix letters in the serial numbers.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

316

ORIGIN OF TYPE 2 NUMBERING

The following discussion on the conversion to type 2 numbering is synthesized from memos and

letters in the Bureau of the Public Debt files (various dates), supplemented by correspondence in the central

correspondence files of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing (1913-1939), both of which are in the

National Archives.

At first, the primary incentive to convert to the type 2 numbering style was annoyance on the part

of bankers that they still had to cut the notes from their sheets. Needed were notes numbered in numerical

order that could be separated and packaged like other currency.

Requests for deliveries in note form from bankers across the country were reaching all the agencies

involved with the national bank issues. Important was a lobbying effort in late March, 1930, by a Mr.

Mountjoy of the American Bankers Association requesting that serious consideration be given to the matter

(Broughton, Mar 23, 1930).

By 1930 the agency people already were converging on the idea of delivering the notes to the banks

in 100-note packages. There were proposals for the Comptroller’s office to purchase cutting machines so

operatives there could cut the sheets before shipping them to the banks. An alternative proposal was for the

Comptroller to return the 4.5 million sheets in his inventory to the Bureau to have them cut and packaged

over there.

However, the problem of multiple notes with the same serial number on the type 1 sheets loomed

large in the deliberations for change. The problem was that the repetitious serials would confounded

bookkeeping after the notes were separated because like numbers would cause confusion in packaging the

notes and the accounting for them.

The agency people were facing another problem that was even worse. From the outset of the 1929

issues, the Redemption Agency was receiving mutilated notes where the bank information was completely

washed off making identification by bank of issue difficult to impossible. However, sorters often could read

the serial numbers because the brown ink penetrated more deeply into the paper than the black ink used to

overprint the bank information. Furthermore, if a badly eroded note was sent in for redemption, the core of

the note surrounding the portrait usually was intact, whereas the borders containing the black charter

numbers might be totally missing.

The plan quickly evolved that if new numbering blocks had to be purchased to allow for consecutive

numbering down the sheet, they could also be designed to add charter numbers adjacent to the respective

sides of the portrait. The advantage of the extra charter numbers was that they would be printed with the

deeper penetrating brown ink and they would be placed in the critical core of the note.

Figure 3. This is the very first type 2 $50 that was printed. The number 1 type

2 sheets for all five denominations for this new Chicago bank were part of a

printing order for $600,000 placed with the Bureau of Engraving and Printing

on May 31, 1933. This order happened to contain the first request for type 2

$50s and $100s. They were delivered from the BEP to the Comptroller on June

24th.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

317

Thus, the type 2 concept would kill two birds with one stone: (1) consecutively number the notes,

and (2) add two charter numbers to facilitate identification of mutilated notes.

The idea for including the two charter numbers in brown came from William S. Broughton,

Commissioner of the Public Debt Service in a memo to Bureau Director Alvin W. Hall dated April 2, 1930.

Broughton suggested that the charter and serial numbers be stacked on the respective sides of the notes.

Putting the numbers in-line with the charter numbers adjacent to the portrait was the suggestion of

Director Hall in a response dated April 22, 1930. Hall was concerned about potential crowding and overlap

of design elements on the notes if the numbers were stacked. Besides, having the numbering discs for the

two numbers on the same axle within the numbering blocks was far easier to accommodate mechanically.

The fact is that the discussions leading to the adoption of the type 2 numbering style progressively

focused more on the additional brown charter numbers than on providing pre-cut notes for the bankers!

Leading the charge for the additional brown charter numbers was the Redemption Agency staff.

The agency people dithered even though there was consensus on the merits of the type 2 concept

in early 1930, so implementation stalled. But time marched on.

On April 28, 1931, Mr. Broughton signaled the frustration of Treasury officials when he wrote to

BEP Director Hall: “Something should be done about National bank notes. Everyone has agreed (1) that

the notes should be separated before shipment, and (2) that additional means of identifying the bank of issue

should be provided. * * * Moreover, the Secretary has promised the banks in due course that the notes will

be delivered separated. * * * Several plans have been considered and at least one has been approved but

misunderstandings or complications have invariably arisen which have prevented the proposal being carried

out” (Broughton, Apr 28, 1931).

Broughton’s memo was designed to light a fire under the agencies, the BEP in particular. Instead

the issue smoldered and weakly at that.

An interagency Currency Committee was formed and recommended on July 18, 1932, that the BEP

be authorized to purchase new numbering blocks to print the type 2 notes. The committee went on to explain

“It has been the purpose of the Department to furnish the banks with separated notes but the difficulties are

so great that it is deemed wise to give no further consideration to the matter at this time” (Broughton and

others, Jul 18, 1932).

Broughton, a member of the Currency Committee, wrote lamely two days later to Assistant

Secretary of the Treasury James H. Douglas Jr. (Broughton, Jul 20, 1932):

National bank notes are produced as job orders. It is not practicable to

separate and exactly collate National bank notes at the Bureau. It would

add many times to the cost. It is possible to separate the notes without

undue expense, but not to collate them. If a change from sheet to separated

notes were made the Comptroller=s vault equipment would be wholly

obsolete. A complete change in vault control and shipping procedure

would be necessary at considerable expense and reduced security. The

present is considered a bad time to make a change, and so the proposal to

separate notes before shipment is being abandoned for the time-being.

Figure 4. $50 and $100 type 2

notes are highly prized because

they were issued in small

quantities by a limited number

of banks. Only 288 of these

$100s were printed for and

issued by this bank. Photo

courtesy of William Herzog.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

318

The recommendations of the committee were approved August 1, 1932 by Douglas. All the agency

people agreed that the addition of the extra charter numbers printed in the deeper penetrating brown ink

next to the portraits was sufficient justification on its own merits to make the change.

Deputy Comptroller of the Currency Frank Awalt sent a memo to Broughton on November 21,

1932 stating “. . . it is requested that each denomination for each bank start with A000001 as it will greatly

facilitate the keeping of records of this office (Awalt, Nov 21, 1932).” Orders were then placed for the new

numbering blocks.

The first order for type 2 notes was requisition number 1099 sent from the Comptroller’s office to

the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on May 13, 1933 (CofC, 1929-1935). The instructions on how to set

up the presses to do this work were finalized in the serial numbering section on May 24, 1933 (BEP,

undated). The first of the type 2 sheets was sent from the Bureau to the Comptroller’s office on May 27,

1933, with $5s for Demopolis, Alabama (10035), $10s for Denver, Colorado (1651) and $20s for

Williamstown, New Jersey (7265) leading the pack. The last type 1 sheets were sent two days later (BEP,

1924-1935).

Separation of the notes never did occur. Delays were caused by deciding whether the Bureau of

Engraving and Printing or the Comptroller’s office should separate the notes. The favored option was to

have the Bureau do the cutting.

If the Bureau was to separate and handle the notes, suitable vault space with furnishings and

equipment had to be arranged, additional counters had to be hired, and new procedures had to be developed

for distributing the notes directly to banks without the notes having to pass through the Comptroller’s office.

Also, it was desirable to wait until the stocks of type 1 sheets could be depleted because handling them in

separated form was undesirable for accounting purposes.

No progress was made on cutting the sheets by the time the series was phased out in 1935. The

long-sought desire of bankers to receive their notes in individual form had been a topic of discussion since

the inception of the series, yet the only progress in that direction was to start numbering the notes

consecutively down the sheets beginning belatedly in 1933.

The fact is, the bankers lost out because it was inconvenient for the agencies to separate the notes.

Besides, there remained large numbers of type 1 sheets in the Comptroller’s inventory that would be a pain

Figure 6. The numbering

wheels for the brown charter

numbers turned on the same

axle as the adjacent serial

number. In this case, the wrong

charter number was dialed in

for $5 serials 1501-3264,

received at the Comptroller’s

office September 23, 1933.

Figure 5. This Mount Olive

bank had the highest charter

number to appear on a type 2

$100. The entire issuance from

the bank consisted of 250 of

these 100s.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

319

to deal with thanks to the repetitious sheet serial numbers on them.

There was momentary consideration of simultaneously shipping type 1 notes to the banks in sheet

form and the type 2s in cut form, but this idea was quickly dropped because the bankers receiving the type

1s would feel discriminated against and probably would howl loudly.

Ironically, there was a bookkeeping benefit to both the Comptroller’s office and the Redemption

Agency attending the use of the type 2 sheets. No longer was the Redemption Agency bound to certifying

redemptions in 6-note increments. Instead they could report and clear all redemptions exactly as they came

through, and the Comptroller’s clerks could issue new notes in serial number order to those exact amounts

by cutting the necessary numbers of notes from sheets if need be.

The practice of cutting one or more notes from sheets to make up deliveries to offset redemptions

closed out the type 2 era and explains why the final type 2 serials issued to many banks are not evenly

divisible by 6.

The irony in all of this is that the primary incentive to adopt type 2 numbering was so that individual

notes could be delivered at great convenience to the bankers. The actual reason that type 2 numbering was

adopted was to take advantage of the duplicate charter numbers that were applied incidentally in the process

in order to facilitate identification of mutilated notes turned in for redemption.

Banker constituency: strikeout! Agency personnel: homerun!

B-SUFFIX TYPE 1, B-PREFIX TYPE 2 SERIAL NUMBERS

A bank had to issue 999,999 sheets of one denomination, for a total of 5,999,994 notes, before B-

suffix serial numbers could appear on a type 1 note. The Chase National Bank of the City of New York

(2370) was the only bank in the country to achieve this distinction. The feat was realized in their $5 issues

in 1933.

The first B-suffix notes arrived at the Comptroller’s office in a printing delivered March 9,

consisting of sheets 1 through 11,140. The shipment to the bank containing the first B-suffix notes went

out December 11 in a group numbered 905141A through 651B. Fortunately, someone at the bank saved the

top notes off the 999999A-1B rollover sheets.

The last type 1 $5 printed for the Chase bank was F057756B and it was issued, yielding a total

issuance of 6,346,530 $5 type 1 notes having a face value of $31,732,650!

Getting to the B

prefix in the type 2 issues was

six times easier. Only 999,996

notes of the same

denomination had to be

consumed first. Bank of

America National Trust and

Savings Association, San

Francisco (13044), was the

only bank to earn this

distinction, and it was done

with their $5s. However,

reaching the B-prefix was just

part of the story.

The printing

containing the B000001 note

Figure 7. Sensational rollover

pair of notes from A- to B-suffix

serials numbers, a feat attained

only by The Chase National

Bank of the City of New York.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

320

was enormous, consisting of notes A371997 through C074856. It arrived at the Comptroller’s office on

November 24, 1933. The A999996-B000001 pair was shipped to the bank December 7, 1934, in a group

numbered A917635-B000938.

The clock ran out on the Series of 1929 before the C-prefix notes were reached. Consequently, the

highest serial sent to the bank was B172602. By then the bank had received $5,862,990 in type 2 $5s.

The highest serial numbers printed on the two types of nationals were as follows according to a

journal maintained by someone in the numbering division (BEP, undated). The dates listed are when the

last were numbered. The serials followed by # were issued.

Type 1:

$5 A-F057756B# Chase National Bank of New York

$10 A-F750580A# Chase National Bank of New York

$20 A-F129054A# Bank of America NT&SA, San Francisco

$50 A-F011178A# Bank of America NT&SA, San Francisco

$100 A-F008554A Union Planters NB&TC of Memphis

Type 2:

$5 C074856 Bank of America NT&SA, San Francisco Nov 11, 1933

$10 A762420# Bank of America NT&SA, San Francisco Apr 27, 1934

$20 A435444# Bank of America NT&SA, San Francisco Nov 3, 1934

$50 A064548 Bank of America NT&SA, San Francisco Nov 3, 1934

$100 A043032 Bank of America NT&SA, San Francisco Nov 3, 1934

PART SHEETS IN BANK SHIPMENTS

The published listings of issued Series of 1929 serial numbers contain numerous entries where part

sheets of type 1 and type 2 sheets were sent to banks. Early during the type 1 issues, it was the practice of

the clerks who were making up shipments to cut sheets in order to round up the dollar totals to exactly

offset the value of redemptions. This produced a bookkeeping headache, so the practice ceased in short

order, probably before 1930, and from then on, the redemption agency reported redemptions in quantities

that exactly equaled values that could be covered by full sheets. In this way, the Comptroller’s clerks

Figure 8. Bank of America

National Trust and Savings

Association, San Francisco,

was the only bank to issue type

2 notes with a B prefix.

Figure 9. There is no photo of

the unique $20 Series of 1929

Type 2 note with serial

A000193 from this bank with

president M. D. Pond’s

signature. We have no idea if it

was saved. A photo of this $10

with Rhoades’ signature will

have to do! Photo courtesy of

Gerome Walton.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

321

avoided the bother of cutting sheets and the laborious ledger work needed to keep track of them.

The advantage of type 2 serial numbers was that they were numbered down the sheet. If a sheet had

to be cut to make a shipment, it caused no bookkeeping headache, so the practice of cutting sheets resumed

during the type 2 era.

There is one tale involving the type 2 issues for The First National Bank of Lyons, Nebraska (6221),

that involved cutting sheets to make up shipments that is so good, it has to be told. The facts here were

discovered many years ago when Gerome Walton asked Huntoon to identify the changeover serial numbers

between signature combinations for several Nebraska banks.

A new president was appointed for the Lyons bank in February 1935. Specifically, M. D. Pond

replaced Herbert Rhoades. A new type 2 printing consisting of $10 and $20 sheets was made with Pond's

signature.

However, the Comptroller’s clerks continued to send notes to the bank with Rhoades’ signature

until stocks of them ran out. Thus, Pond=s sheets waited in inventory.

As fate would have it, the very last shipment to the bank to offset redemptions before the Series of

1929 was discontinued involved an amount that required one $20 note be cut from the next sheet.

You guessed it, that single $20 was the only 1929 note shipped to the bank with president Pond’s

signature! The note was $20 serial A000193 sent April 29, 1935, along with some sheets with Rhoades’

signature. No $10s with Pond's signature were sent.

Of all the notes sent to the bank, that one was the most likely to have been saved by Pond. I wonder

if he saved it! It has not been reported. Probably it is hanging on the wall of his grandson’s office. Or maybe

his great grandson liberated it in order to go out and buy some weed!

SERIAL NUMBER GAPS IN BANK SHIPMENTS

It was the policy of the Comptroller’s office to consume stocks of sheets having obsolete signatures

before notes with new signatures were shipped. The same was true for new titles.

Despite this policy, gaps consisting of sizable groups of unissued serial numbers have been

recognized for 44 different banks in the 1929 issues. The gaps usually affected all the denominations being

issued by the bank at the time.

The gaps occurred in one of two ways. It is clear that bankers could request that unissued sheets

with obsolete titles or signatures be canceled because this occasionally happened. Such cancellations

explain most of the gaps. The few others represent canceled misprint runs discovered after the sheets had

been delivered to the Comptroller of the Currency.

Not all the canceled runs of obsolete signatures have been identified. There are two reasons they

were missed.

First, many signature changes happened to occur between the type 1 and 2 issues. Canceled sheets

from the ends of type 1 printings can be detected only by determining if, in fact, the last type 1 sheets

printed were actually issued. This requires an examination of the appropriate National Currency and Bond

Ledger for every affected bank in the National Archives, a detail that wasn’t consistently undertaken.

Second, and even more obscure, is that in many cases, Louis Van Belkum, the compiler of the

issued national bank note serial numbers, calculated the last serial numbers issued by using summary dollar

totals from the last ledger page, rather than examining the ledger page that showed the actual high serial

numbers issued. He would thus miss the fact that there was a group of canceled sheets, and inadvertently

calculate ending serial numbers that were correspondingly too low. Occasionally we find such missed gaps

when collectors report out of range serial numbers.

Three examples of gaps resulting from misprinted orders follow.

Jamaica Errors

The Series of 1929 type 1 printings for The Jamaica National Bank of New York (12550) were

jinxed by a succession of two consecutive typesetting errors.

The first involved a stopgap 6-subject electrotype plate made by the Government Printing Office

came with Jamaica in the F-position misspelled Jamacia. This typo was made by a BEP linotype operator

as he was making the type for a 6-subject form that was used by the GPO as a mold for the plate. In the

meantime, Barnhart Brothers & Spindler, the Chicago contractors awarded the contract for providing sets

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

322

of six 1-subject logotype

plates, had received their

order for the bank’s plates,

but that order omitted the

“of” from the bank title. In

due course, the BBS

logotypes arrived.

The first printing for

the bank was made from the

GPO plate and some sheets

were sent to the bank with the

misspelling in the F-position

before it was discovered. The

remainder of that printing

was canceled, and followed

by printings from the finally

arrived BBS logotypes. The

omitted “of” wasn’t detected

until a new plate was ordered

by the bankers to reflect a

new president in 1933. Table

1 summarizes the salient

facts surrounding this

comedy of mistakes.

The discovery of the

Jamacia misspelling and

cancelation of the remaining

stock of those sheets in the

Comptroller’s inventory

explains the gap in the issued

serial numbers. This gap is

particularly interesting

because the issuance of the

error sheets was terminated

mid-sheet. At the time the

Comptroller’s clerks cut

sheets to make up desired

dollar amounts in their

Figure 10. Three notes from

The Jamaica National Bank of

New York. Top: John

Hickman’s photocopy of the

F-note with misspelled

Jamacia from the GPO plate.

Middle: note from the BBS

logotypes with omitted of in

the title. Bottom: note from a

new set of BBS logotypes made

in 1933 with the correct title

when the president=s signature

was changed.

Table 1. Receipts of key serial numbers for The Jamaica

National Bank of New York (12550) at the Comptroller

of the Currency's office.

Data from Comptroller of the Currency, 1863-1935.

Date Den Serials Delivery

Type 1:

6-subject GRO plate containing misspelling in the F-position

Sep 7, 1929 5 1-208 1st type 1 delivery

10 1-406

1st set of six 1-subject BBS logotypes missing "of"

Nov 25, 1929 5 209-410 2nd type 1 delivery

10 407-824

Dec 2, 1932 5 4021-4544 last type 1 delivery

10 4371-5196

Type 2:

2nd set of six 1-subject BBS logotypes with new president

Aug 19, 1933 5 1-4956 1st type 2 delivery

10 1-6792

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

323

shipments.

Louis Van Belkum had recorded

the gap from the National Currency and

Bond Ledgers, but, of course, we had no

idea what had caused it. John Hickman

provided the vital clue decades ago. One

day he excitedly showed me a photocopy

someone had sent him of the bottom four

notes from the $10 number 2 sheet from the

first printing sporting the misspelled

Jamacia in the F-position. The National

Currency and Bond Ledgers revealed that

the Comptroller’s clerks sent the unissued

error sheets to the redemption division for

cancellation as soon as the error was

discovered

Bartlett, Texas, Misspelling

The first two printing of Series of

1929 notes for The First National Bank of

Bartlett, Texas (5422), had the town misspelled Barlett.

This spectacular error, the first to be reported from the bank, came in a lot of Texas notes consigned

to Heritage Auctions and offered through their January 5-8, 2011 Fun sale. Heritage cataloguer Frank Clark,

spotted the error.

He sent a scan of it to Huntoon, not knowing that Huntoon had discovered the error in Treasury

records several years ago, already had researched it, and been looking for a specimen ever since.

Huntoon first ran into the misspelling in a Bureau of Engraving and Printing billing ledger for

Series of 1929 overprinting plates. The entry for The First National Bank of Bartlett was written during

September 1929, and shows

the spelling as Barlett. It

appears that the misspelling

was transmitted to the BEP

on the order form that they

received from the

Comptroller of the Currency.

The September

entry is followed by an

undated second that states

“new plate[s] made without

charge to bank.”

Both sets of plates

were made by Barnhart

Brothers & Spindler in

Chicago.

The rest of the story

appears in the National

Currency and Bond Ledgers.

The first delivery of 1929

sheets for the bank arrived at

the Comptroller’s office on

September 25, 1929, and

contained $10 sheets 1-616 Figure 11. Bartlett is misspelled in the top note of this pair.

Table 1, continued.

Dates when key notes were shipped to the bank.

Type 1:

6-subject GRO plate containing misspelling in the F-position

Sep 17, 1929 10 A1-B4

Sep 27, 1929 5 A1-B14

Oct 5, 1929 10 C4-D7

Oct 15, 1929 10 E7-B14

Oct 30, 1929 10 C14-B19

(rest of first printing canceled)

1st set of six 1-subject BBS logotypes missing "of"

Nov 25, 1929 5 209-

Nov 26, 1929 10 407-

Aug 4, 1933 10 -5196

Aug 11, 1933 5 -4544

Type 2:

2nd set of six 1-subject BBS logotypes with new president

Aug 19, 1933 5 1-

Aug 19, 1933 10 1-

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

324

and $20s 1-210.

Error sheets began to be shipped to the bank beginning with $10s on October 4, followed by $20s

on October 12. These were replacements for worn large size notes that had been redeemed. Periodic

shipments followed.

The cryptic notation “printed wrong” appears in the column showing shipments to the bank, so it

is clear that the clerks spotted the misspelling.

A second printing arrived at the Comptroller’s office four and a half months later on February 8,

1930. Ironically, it was printed from the plates with the misspelling and included $10s 617-1234 and $20s

211-422. Obviously, an order for more sheets had been sent to the BEP, but failed to mention the

misspelling.

The last shipment of sheets with the misspelling was sent to the bank February 4, 1930, four days

before the second printing arrived.

The arrival of the second printing stirred the Comptroller’s office into remedial action. They

ordered a third printing with the proper spelling.

It arrived at the Comptroller’s office on February 26th, and contained sheets $10s 1235-1836 and

$20s 423-832, so now the clerks finally could stop shipping errors! The first shipment to the bank without

the misspelling went out that same day.

The unissued sheets with the misspelling were canceled May 12, 1930, and included serials $10

460-1234 and $20 116-422. Notice that the cancellations involved the last sheets in the first printing and

all the sheets from the second printing. This is another case where a typographical error on the layout used

to make Series of 1929 overprinting plates resulted in canceled sheets and resulting gaps in issued serial

numbers.

The part of this tale that is interesting is that even though the error was spotted in September 1929,

the Comptroller’s office continued to ship the misprints until a corrected printing arrived. Misprints, when

found, always caused some type of response. Procedures varied, but a primary consideration involved

weighing the degree of the problem against an inconvenient wait imposed on the bankers. Delays were

obviously considered worse than the misspelling in the Bartlett case!

A key step in making the Series of 1929 logotype plates that were produced by Barnhart Brothers

& Spindler involved a photo etching process. This required a photo positive of the overprint. A photo

positive of Bartlett was spliced into the original positive in place of Barlett. All else on the layout was left

as it was. The new set of plates was made from the corrected positive.

Another misspelling of a town is flagged in the 1929 billing ledger. This occurred on the plates

made for The First National Bank of Maquoketa, Iowa, charter 999. The July 1929 billing entry states

“misspelled Maquoleta.” In this case, the BEP ordered a new set of overprinting plates before the first

printing. Notes from the first printing came out correctly as Maquoketa, including most notably the $20

E000001A note that appeared in a CAA 1/97 sale.

Indianapolis Preposition Error

A general policy had been adopted at the Comptroller’s office not to accepted titles that duplicated

one used previously in the same town. They could be avoided by substituting in or at for of in titles, or by

dropping those prepositions altogether.

This resulted in a glitch for an Indianapolis bank. The American National Bank at Indianapolis was

the third in a string of related banks. The first was The American National Bank (5672), chartered in 1901,

which was liquidated and reorganized as The Fletcher American National Bank (9829) in 1910. The

Fletcher American was in turn liquidated January 24, 1934, and succeeded by The American National Bank

at Indianapolis (13759), which had been organized August 19, 1933. In the case of charter 13759, at was

substituted for of

The officers of the new bank arranged for a deposit of $1 million worth of bonds to secure a like

circulation on February 28, 1934. A set of Series of 1929 overprinting logotypes was made, and the first

deliveries from them arrived at the Comptroller’s office in October 1933. A subsequent printing was

delivered in February 1934. $1 million was shipped to the bank March 1st from the Comptroller’s office.

What everyone failed to notice was that the title on the first two printings used the traditional of

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

325

instead of at! The error was

spotted once the $1 million

worth of errors arrived at the

bank. The notes were

desperately needed, so they

were pressed rapidly into

circulation.

In the meantime, the

unissued remainders in the

Comptroller’s office from the

second printing were canceled

March 15th. A third shipment

with the corrected title arrived

at the Comptroller’s office

March 26-27, 1934. Another

followed in September. Consequently, there were gaps in the issued serial number ranges for all five type

2 denominations between the two titles.

Regular shipments to the bank of error-free notes from the new plates were used to offset

redemptions of worn notes from circulation beginning April 12, 1934. In this interesting case, $286,770

worth of error-free notes were sent to the bank, in contrast to a million dollars’ worth of the errors.

Consequently, the errors represented about three and a half times the dollar value of the non-errors! The

fact is that the error-free notes proved to be fairly difficult to find.

MATCHED CHARTER AND SERIAL NUMBERS

Occasionally someone finds a note where the serial number matches the charter number. Just that

happened to Dan Freeland with the circulated note from Bay City, Michigan, shown here. Lucky find!

PARTING COMMENTS

The great advantage to bankers with the adoption of small size national bank notes was that the

notes would arrive in totally completed form; specifically, they already would bear the bank signatures.

However, in reality the conversion to small size got off on the wrong foot because the notes were still

Figure 13. Notice that the

charter number and serial

number match on this Bay City,

Michigan, note.

.

Figure 12. The official title for

this Indianapolis bank utilized

the preposition at, not of. The

first two printings used of by

mistake. Notes with the error

are more easily obtained than

the corrected title.

SPMC.org * Paper Money * Sep/Oct 2022 * Whole Number 341

326

printed in sheets where every note on the sheet had the same number, a tradition inherited from the large

note era, which in turn had been inherited from the numbering of obsolete bank currency before that by the

bank note companies. As before, the notes were sent to the bankers in sheet form when what the bankers

really wanted was separated notes. These comprised the type 1 varieties printed from 1929 to 1933.

All relevant Treasury officials undertook deliberations to remedy this shortcoming and the concept

of consecutively numbered notes gained serious traction. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing could

readily handle consecutively numbered notes because that is how all Treasury and Federal Reserve bank

currency was being numbered. The Bureau was using small size numbering presses that not only applied

the numbers consecutively down the sheet, but also separated and collated the notes in consecutive order.

Consecutively numbering down the sheets was adopted for nationals in 1933 giving rise to the type

2 varieties. However, the primary internal motivation for moving in this direction was that the new

numbering heads were designed to also apply the bank charter numbers next to the serial numbers, yielding

two additional charter numbers that were printed using brown ink. That ink penetrated the paper better than

the black ink used for the two black charter numbers along the outside edges of the notes that were part of

the bank overprint. The reality was that the National Bank Redemption Agency was facing two serious

problems. Often the black overprints on worn notes had washed off making it difficult or impossible to

assign those redeemed notes to the proper bank. On other severely worn notes, the ends were eroded to the

point that the black charter numbers along the edges were missing. The more durable brown charter

numbers bracketing the portraits at the centers of the notes solved both problems!

Once they began to produce the type 2 notes, they continued to send them to the banks in uncut

form. The decision turned on convenience. The Comptroller’s vault was set up to handle sheets, not

individual notes. Besides, there was a huge inventory of type 1 sheets still in stock. In order to convert to

notes, everything involved with handling including the design of the vault itself would have to be changed.

Not the least of the problems was that the type 1 sheets in inventory would have to be separated into

individual notes, which would bear duplicate numbers that would create an accounting headache.

The solution was simply to defer dealing with the problem. If they waited long enough, the stock

of all the type 1 sheets would finally be consumed. Also, on the horizon was the happy prospect that serious

minds in the Treasury Department were working on doing away with the nuisance national currency

altogether. Waiting things out deferred costly intervention! And that is how the type 2 era played out.

There was one benefit to the type 2 issues from the perspective of the Comptroller’s office.

Bookkeeping could be simplified because replacements for worn notes redeemed from circulation could be

handled when necessary by cutting sheets to supply exact balances rather than juggling redemption balances

to match the dollar value of full sheets as was the practice going into the type 2 era.

As for the bankers, whose howls fueled the move to consecutively number the notes, they were

stuck with having to deal with annoying sheets right up to the end!

REFERENCES CITED AND SOURCES OF DATA

Awalt, F. G., Deputy Comptroller of the Currency, Nov 21, 1932, Memorandum to William S. Broughton, Commissioner of the

Public Debt Service, requesting that Series of 1929 type 2 serial numbering start at A000001: Bureau of the Public Debt,

Series K Currency, Record Group 53, U. S. National Archives, College Park, MD.

Broughton, William S., Commissioner of the Public Debt Service, Mar 23, 1930, Memorandum to Alvin W. Hall, Director, Bureau

of Engraving and Printing, pertaining to a request from Mr. Mountjoy of the American Bankers Association to consider

separating Series of 1929 national bank notes prior to delivery to the banks: Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Central

Correspondence Files, Record Group 318, U. S. National Archives, College Park, MD.

Broughton, William S., Commissioner of the Public Debt Service, Apr 2, 1930, Memorandum to Alvin W. Hall, Director, Bureau