Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

Issuance & Redemption of Aldrich-Vreeland Emergency Currency--Lee Lofthus

Update on Wade $10 Silver Certificate Article--Huntoon, Lofthus, Moffitt

Treasury Sealing Assigned to Treasurers Office--Peter Huntoon & Doug Murray

Postmaster Marshall Left Holding the Bag--Bob Laub

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

Issuance & Redemption of

Aldrich-Vreeland Emergency Currency

America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

1550 Scenic Ave., Suite 150, Costa Mesa, CA 92626 • 949.253.0916

470 Park Ave., New York, NY 10022 • 212.582.2580 • NYC@stacksbowers.com

84 State St. (at 22 Merchants Row), Boston, MA 02109 • 617.843.8343 • Boston@StacksBowers.com

1735 Market St. (18th & JFK Blvd.), Philadelphia, PA 19103 • 267.609.1804 • Philly@StacksBowers.com

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • Boston • Philadelphia • New Hampshire • Oklahoma • Virginia

Hong Kong • Paris • Vancouver

SBG PM AugGlobal2024 HLs 240501

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Contact Our Experts for

More Information Today!

Consign@StacksBowers.com

August 2024 Global Showcase Auction Highlights from

STACK’S BOWERS GALLERIES

An ANA World’s Fair of Money® Auctioneer Partner

August 12-16 & 19-22, 2024 • Consign U.S. Currency by June 17, 2024

Highlights from The Porter Collection

Fort Benton, Montana Territory. $5 1875.

Fr. 404. The First NB. Charter #2476.

PMG About Uncirculated 53.

Beaumont, Texas. $20 1882 Brown Back.

Fr. 504. The Citizens NB. Charter #5841.

PMG Choice Uncirculated 64 EPQ.

Guthrie, Territory of Oklahoma.

$10 1882 Brown Back. Fr. 485. The Capitol NB.

Charter #4705. PMG Choice Very Fine 35.

Serial Number 1.

Vinton, Virginia. $10 1902 Plain Back.

Fr. 633. The First NB. Charter #11911.

PMG About Uncirculated 53. Serial Number 1.

Fr. 126b. 1863 $20 Legal Tender Note.

PMG Choice Uncirculated 64 EPQ.

Fr. 152. 1874 $50 Legal Tender Note.

PMG Choice About Uncirculated 58.

Fr. 151. 1869 $50 Legal Tender Note.

PMG Choice Very Fine 35.

Fr. 212d-I. July 15th, 1865 $50 Interest

Bearing Note. PMG Very Fine 20.

Peter A. Treglia

Director of Currency

PTreglia@StacksBowers.com

Tel: (949) 748-4828

Michael Moczalla

Currency Specialist

MMoczalla@StacksBowers.com

Tel: (949) 503-6244

158 Issuance & R3demption of Aldrich-Vreeland Emergency Currency--Lee Lofthus

197 Update on Wade $10 Silver Certificate Article--Huntoon, Lofthus, Moffitt

202 Treasury Sealing Assigned to Treasurers Office--Peter Huntoon, Doug Murray

220 Postmaster Marshall 'Left Holding the Bag--Bob Laub

214 Uncoupled--Joe Boling & Fred Schwan

222 Cherry Pickers Corner--Robert Calderman

224 Obsolete Corner--Robert Gill

226 Chump Change--Loren Gatch

227 Quartermaster Column--Michael McNeil

230 UNESCO-Antigua--Roland Rollins

231 Small Notes--Jamie Yakes

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

153

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Mark Anderson

Doug Ball

Hank Bieciuk

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Forrest Daniel

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Brent Hughes

Glenn Jackson

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Clifford Mishler

Barbara Mueller

Judith Murphy

Dean Oakes

Chuck O'Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

John Rowe III

From Your President

Editor Sez

New Members

Uncoupled

Cherry Picker Corner

Obsolete Corner

Chump Change

Quartermaster

UNESCO

Small Notes

Robert Vandevender 155

Benny Bolin 156

Frank Clark 157

Joe Boling & Fred Schwan 214

Robert Calderman 222

Robert Gill 224

Loren Gatch 226

Michael McNeil 227

Roland Rollins 230

Jamie Yakes 231

Stacks Bowers Galleries IFC

Pierre Fricke 153

Bob Laub 174

FCCB 176

Higgins Museum 178

Fred Bart 180

Whatnot 195

Lyn Knight 196

Bill Litt 201

PCGS-C 213

Greysheet 219

World Banknote Auctions 221

Whitman Publishing 232

PCDA IBC

Heritage Auctions OBC

Fred Schwan

Neil Shafer

Herb& Martha Schingoethe

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

154

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT Robert Vandevender II

rvpaperman@aol.com

VICE-PRES/SEC'Y Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Robert Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

APPOINTEES

PUBLISHER-EDITOR ADVERTISING MGR

Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

Megan Reginnitter mreginnitter@iowafirm.com

LIBRARIAN

Jeff Brueggeman

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark frank_clark@yahoo.com

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Shawn Hewitt

WISMER BOOk PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Robert Vandevender II

From Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

jeff@actioncurrency.com

LEGAL COUNSEL

Robert Calderman gacoins@earthlink.com

Matt Drais stockpicker12@aol.com

Mark Drengson markd@step1software.com

Pierre Fricke pierrefricke@buyvingagecurrency.com

Loren Gatch lgatch@uco.edu

Derek Higgins derekhiggins219@gmail.com

Raiden Honaker raidenhonaker8@gmail.com

William Litt billitt@aol.com

Cody Regennitt

Andy Timmerm

Wendell Wolka

er cody.regennitter@gmail.com

Once again, Spring has arrived, bringing us nicer weather. Although my

“temporary” job in California was supposed to last eight months, in April, I

completed five years in San Clemente. I do expect the job to end sometime

later this year and I will return home. A byproduct of this situation has the

potential to turn me into a Delta Airlines “Million Miler” either late this year

or early in the next year.

In mid-February, we learned the sad news that our SPMC Governor, Jerry

Fotchman, passed away in Texas. Jerry also served as the President of the

Fractional Currency Collectors Board for many years. Jerry was a very

active and engaged member of our board and routinely contributed to our

efforts. He will be missed by all of us.

In March, our board member, Derek Higgins, and his wife Jessica, also an

SPMC member, staffed a table representing the SPMC at the ANA National

Money Show in Colorado Springs, CO. I personally have never been to

Colorado Springs. Taking a tour of the ANA Money Museum is on my

bucket list for a future visit.

On April 8th, Nancy and I joined several of our family members in Indiana

to witness the total solar eclipse. My daughter, Holly, hosted the watch party

at her home. In addition to plenty of food to eat, she ensured several types of

snacks such as Sun Chips, Moon Pies, Little Debbie Cosmic Brownies were

available! The weather cooperated and we had a spectacular view of the

100% eclipse, being able to remove our glasses for about three and a half

minutes during totality.

No doubt many of you attended the 3rd annual National Banknote

Collectors Conference in Dallas. I am looking forward to hearing about the

event and hope to be able to attend the next one.

I continue to enjoy reading the various posts on social media. Recently,

there have been many posts regarding web-fed notes and comments by

various new collectors who weren’t aware of that variety of notes. Many of

our members routinely answer questions, which appears to be helping several

new collectors come up to speed on the hobby. I encourage each of you to

continue to educate potential new collectors in this regard.

The SPMC is planning to staff a table at the Chicago ANA World’s Fair of

Money in August. If you make it to the show, please stop by and say hello!

an andrew.timmerman@aol.com

purduenut@aol.com

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

155

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY (USPS 00‐

3162) every other month beginning in January. Periodical

postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055, Gainesville,

GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2020. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole or part

without written approval is prohibited. Individual copies of this

issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the secretary for $8

postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries concerning non ‐

delivery and requests for additional copies of this issue to

the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the editor. Accepted

manuscripts will be published as soon as possible, however

publication in a specific issue cannot be guaranteed. Opinions

expressed by authors do not necessarily reflect those of the

SPMC. Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format via

email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of the author

to the editor for duplication and printing as needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good faith”

basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases where

special artwork or additional production is required, the

advertiser will be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are

not commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC does not

endorse any company, dealer, or auction house. Advertising

Deadline: Subject to space availability, copy must be received

by the editor no later than the first day of the month

preceding the cover date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the

March/April issue). Camera‐ready art or electronic ads in pdf

format are required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

Required file submission format is composite PDF v1.3

(Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted files should

conform to ISO 15930‐1: 2001 PDF/X‐1a file format standard.

Non‐ standard, application, or native file formats are not

acceptable. Page size: must conform to specified publication

trim size. Page bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond

trim for page head, foot, and front. Safety margin: type and

other non‐bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”.

Advertising c o p y shall be restricted to paper currency, allied

numismatic material, publications, and related accessories.

The SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject objectionable

or inappropriate material or edit copy. The SPMC

assumes no financial responsibility for typographical

errors in ads but agrees to reprint that portion of an ad in

which a typographical error occurs. Benny

Space

Full color covers

1 Time

$1500

3 Times

$2600

6 Times

$4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half‐page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter‐page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth‐page B&W 45 125 225

Welcome to the May/June issue of Paper Money. First and

foremost, let me apologize in advance if this issue comes to you

late or is not the general high quality that is usually put out. This is

the end of school time and this year it has been extremely busy.

Those kids really want summer to come, but we have another

month before that happens. Senioritis strikes all the way down to

the sophomore level! It also strikes at the faculty/staff level as

well--I am as ready as them to get into some much needed time

off. But the main reason for my distraction and lateness, is that on

April 2 when I am usually at the height of putting an issue out, my

mother-in-law passed away quite unexpectedly. Helping my wife

and sister-in-law with that has been tough. Dealing with all the

emotions is bad enough, but dealing with the estate has been very

trying--and it is a simple estate! Oh well, so much for my pity

party and time to move forward.

As we enter into the summer where the show schedule ramps

up big-time, I hope you all are able to attend at least one show.

The camaraderie at shows is, in my opinion, the best part. Seeing

old friends and gaining new acquaintances is great. Of course

scouring that bourse floor for that special note is great too!

Speaking of that special note, I have recently changed the

focus of my collection. No, I am not giving up fractional, but am

pursuing another of my passions with vigor--fractional currency

mimics. These are essentially advertising notes, primarily from the

non-Confederate states issued to combat change issues after the

Civil War. They mimic fractional by having a design that

"mimics" the backs of the third issue 10c, 25c and 50c fractional

currency. While I usually only see about 2-3 of these a year for

sale, this past March and April there evidently was a collection up

for sale with Lyn Knight and Heritage. About 20 have been

offered at auction and I have been lucky enough to get about 15 of

them with more to come during April and maybe May. I say a

collection as there are only a very few duplicates and most are

loners. I now have 122 of them. I like to say, just to make me look

important, that it is the largest collection out there! I have written

an electronic book on the subject (it includes notes payble in

fractional, look-a-likes and kinda-look-a-likes and even includes a

section on college notes with "fractional" on them) and it has now

swelled to over 525 pages!

Anyway, enough about me. I hope you enjoy this and the next

issue as the majority of the article space will be taken up by two

large articles. This issue has an article by Lee Lofths and is on

some WWII currency and next issue Steve Feller will introduce us

to money used in the Japanese-American internment camps of

WWII. I publish them without splitting them as I think that reads

much better.

Till next time! Stay safe and enjoy summer!

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

156

The Society of Paper Money

Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit

organization under the laws of the

District of Columbia. It is

affiliated with the ANA. The

Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the International

Paper Money Show. Information

about the SPMC, including the

by-laws and activities can be

found at our website--

www.spmc.org. The SPMC does

not does not endorse any dealer,

company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and

LIFE. Applicants must be at least 18

years of age and of good moral

character. Members of the ANA or

other recognized numismatic

societies are eligible for membership.

Other applicants should be sponsored

by an SPMC member or provide

suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR.

Applicants for Junior membership

must be from 12 to 17 years of age

and of good moral character. A parent

or guardian must sign their

application. Junior membership

numbers will be preceded by the letter

“j” which will be removed upon

notification to the secretary that the

member has reached 18 years of age.

Junior members are not eligible to

hold office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues

for members in Canada and Mexico

are $45. Dues for members in all

other countries are $60. Life

membership—payable in installments

within one year is $800 for U.S.; $900

for Canada and Mexico and $1000

for all other countries. The Society

no longer issues annual membership

cards but paid up members may

request one from the membership

director with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who

joined the Society prior to January

2010 are on a calendar year basis

with renewals due each December.

Memberships for those who joined

since January 2010 are on an annual

basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due

before the expiration date, which can

be found on the label of Paper

Money. Renewals may be done via

the Society website www.spmc.org

or by check/money order sent to the

secretary.

WELCOME TO OUR

NEW MEMBERS!

BY FRANK CLARK

SPMC MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

NEW MEMBERS 3/05/2024 NEW MEMBERS 4/05/2024

Dues Remittal Process

Send dues directly to

Robert Moon

SPMC Treasurer

104 Chipping Ct

Greenwood, SC 29649

Refer to your mailing label for when

your dues are due.

You may also pay your dues online at

www.spmc.org.

REINSTATEMENTS

None

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

15684 Greg Shaban, Gary Dobbins

15685 Frank Stroik, Website

15686 Craig Norman, Don Kelly

15687 Richard Smith, Website

15688 Steve Neise, Website

15689 Richard Chavarria, Website

15690 David Viga, Website

115691 Adam Miller, Derek Higgins

15692 Marc Shull, Hugh Shull

15693 Bob McNeil, Tom Snyder

15694 Dillon DiVello, Robert Calderman

15695 Reverdy Orrell, Website

15696 Dennis Mohr, Frank Clark

15697 Camden McDonald, Dustin Johnston

REINSTATEMENTS

14508 Jose Serrano, Frank Clark

15223 Rex Nelson, Frank Clark

LIFE MEMBERSHIPS

None

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

157

Protocols for Handling the Issuance and Redemption of

Aldrich-Vreeland

Emergency Currency

Lee Lofthus

Objectives

The purposes of this article are to place the passage of the Aldrich-Vreeland Emergency

Currency Act of 1908 into its historic context and to explain how the issuance and redemption of

the emergency currency authorized by the act worked.

The handling of Series of 1882 and 1902 date back notes authorized by the act imposed

new challenges on the Treasury, the solutions for which were either spelled out in the authorizing

legislation or policies implemented by Treasury officials during their use.

There were three important new considerations. (1) How were the new notes to be phased

in? (2) How did the act provide for the notes to be readily available on short notice to the

subscribing banks? (3) How did Treasury attempt to avoid wasting perfectly good sheets that were

returned when the bankers redeemed their emergency emissions?

The procedures associated with items 1 and 2 above were spelled out in the Aldrich-

Vreeland Act. Item 3 was handled through a Treasury Department policy decision. This article

naturally lends itself to a three-part structure defined by the protocols that governed how the

emergency currency was handled.

Terminology

Aldrich-Vreeland Emergency Currency Act, named for the sponsors of the act, is the most

commonly used handle attached to the act, as is emergency currency for the currency authorized

by it. This nomenclature has been with us since the act was passed. Emergency currency was

widely used among the work force of the various Treasury offices including the clerks in the

Comptroller’s Issue Division who wrote EC next to entries for the currency in their ledgers.

The formal name for the act in the U.S. Statutes is the non-descript “An Act To amend the

national banking laws” (Statutes, AV Act).

The term additional circulation, referring to currency backed by securities other than U.S.

Treasury bonds, was the preferred term by the top Treasury officials and many bankers instead of

emergency currency and appeared in Treasury press releases. Of course, the bland term additional

circulation was used to avoid alarming a jittery public.

For the purposes of this article, Aldrich-Vreeland Act will be used as the title, and

emergency currency will be used because that is what the act was about. Besides, emergency

currency is far more catchy than additional circulation.

Introduction

The Treasury Department and the nation’s national banks took extraordinary measures

after war broke out in Europe in August 1914 to avert a banking panic in the United States. Using

authorities granted by Congress in 1908, and expanded in December of 1913 and again on August

4, 1914, Treasury injected $386 million in emergency currency into the national banking system

during the 28-week period spanning August 4, 1914 to February 12, 1915. The largest amount of

this money in circulation at any one point was $363 million. (Treasury, 1914, p. 530-531).

The mechanism used to create the emergency currency was to allow the bankers to receive

additional, but short-term, national bank note issuances using softer securities than U.S. Treasury

bonds. These included liens against short-term commercial loans, non-Federal government bonds

and other short-term commercial paper that the bankers controlled as backing for loans they made.

The emergency currency was taxed at a higher rate than traditional U.S. Treasury bond-secured

national bank notes, so there was a strong incentive for the bankers to redeem it as soon as it no

longer was needed.

As war in Europe became inevitable, it was anticipated that the crisis could lead to bank

runs and hoarding of cash with the potential to cripple the U.S. economy. An emergency currency

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

159

infusion under the act began just 8 days after the outbreak of the war, ultimately increasing the

outstanding national bank note circulation from $751 million to $1.1 billion dollars, a 50% increase

(Treasury, 1915, p. 577).

The purpose of the currency was to provide the subscribing banks with liquidity in the form

of newly created money. A major value of the emergency currency being made available to the

banks was its calming effect on depositors. The emergency currency, which was designed to have

a short life, also provided the bankers with a temporary pool of funds that offset money withdrawn

from commerce through hoarding.by the public. Thus, the emergency currency afforded bankers

the opportunity to make short-term loans required to keep the economy humming when it was

needed most to tame jittery nerves. The collateral backing those loans served as the security

backing the emergency currency,

Banking Panic in Europe

World War I began in Europe on July 28, 1914 when Austria-Hungary declared war on

Serbia. This set off a chain reaction of war declarations across the continent. Germany invaded

Belgium on August 4th.

Unease in European banks had begun earlier that summer after Archduke Ferdinand and

his wife Sophie were assassinated on June 28. Full-scale bank runs ensued in Berlin, Paris and

other European cities (Hepburn, 1914, p. 437; NYT, Jul 28, 1914 & Aug 7,1914).

Figures 1 and 2. As war broke out,

European depositors feared for their

savings. At top, a crowd gathers outside

the Bank of France in Paris. At bottom,

a run on a Berlin bank after Germany’s

war declaration. Similar desperate

scenes played out in other European

cities. Library of Congress photos LCN

2014697205 and 2014697046.

Figures 1 and 2. As war broke out,

European depositors feared for their

savings. At top, a crowd gathers outside

the Bank of France in Paris. At bottom,

a run on a Berlin bank after Germany’s

war declaration. Similar desperate

scenes played out in other European

cities. Library of Congress photos LCN

2014697205 and 2014697046.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

160

Congress and the U.S. Treasury Department were determined not to let the European

banking contagion spread to the United States. Treasury officials were already well aware of the

looming as the European nations had spent the summer liquidating their securities in the United

States for gold, thus drawing Treasury gold supplies to ominously low levels (Treasury, 1914, p.

34; Hepburn, p. 434, 438). American commercial banking would be next to feel the strain.

Fortunately, the Treasury Department had the tool it needed in the Aldrich-Vreeland Act to avoid

a crisis at home.

The Aldrich-Vreeland Act

The Aldrich-Vreeland Act was passed May 30, 1908 in the wake of the disastrous Panic of

1907 during which the inability of the Treasury to forestall an all-out monetary crisis was laid bare.

Instead of the Treasury stepping up, New York banker J.P. Morgan mobilized a rescue of the

economy from total collapse.

The 1908 Aldrich-Vreeland Act rather clumsily introduced elasticity into the national bank

note supply. Elasticity is the ability of a class of currency to expand or contract as economic

conditions warrant without disruption of the economy.

The act was viewed

in Congress as an

experiment. Thus, it came

with a sunset provision

where its terms expired on

June 30, 1914 (Statutes, AV

Act, Sec. 20).

The emergency

provisions in the Aldrich-

Vreeland Act lay dormant

for six years because no dire

financial stress materialized

and the tax rates on the

emergency currency were

sufficiently high that they

deterred bankers from

casual use of the authority.

The Federal Reserve

Act was signed December

23, 1913 by Woodrow

Wilson, a landmark

achievement that gave the

nation a true elastic currency

(Meltzer, 2003, p. 69-71;

Malburn, Feb 18, 1915).

Congress and Treasury

anticipated a gradual start-

up for the new system so

fortunately included in the

Federal Reserve Act was a

provision that extended the

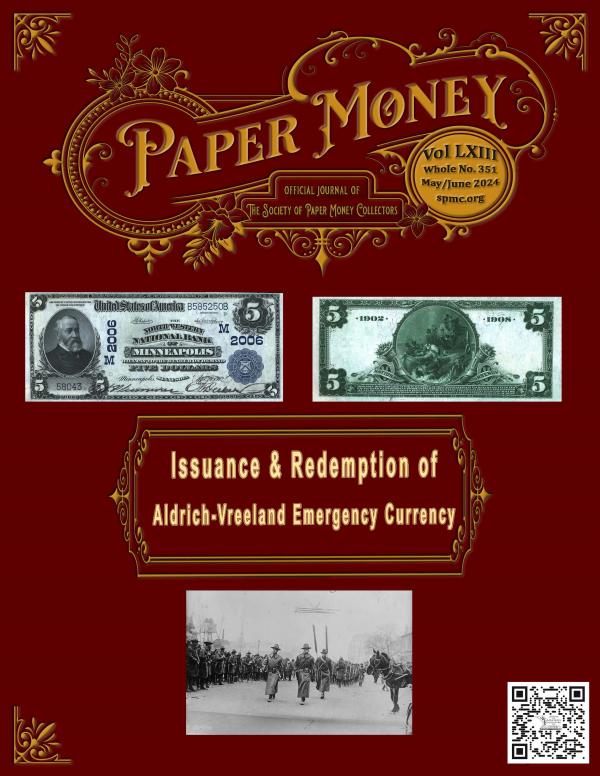

Figure 3. The date back national bank note design had been

introduced by Treasury after the passage by Congress of the

Aldrich-Vreeland Act in 1908. Both Series of 1882 and Series of 1902

date backs were issued. However, none were issued as actual

emergency currency until the war began in Europe in summer 1914.

This particular note is a true emergency note. It was issued to the

bank August 10, 1914, in one of several emergency shipments made

that August after the bank deposited $1.5 million of “other

securities” with the National Currency Association of the Twin

Cities, St. Paul, Minnesota. Heritage Auctions Archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

161

Aldrich-Vreeland Act for another year to June 30, 1915. Thus, the elasticity built into it could

serve as a cushion until the Federal Reserve system became operational (Meltzer, 2003, p. 74, 82).

The Aldrich-Vreeland Act suddenly came into sharp focus with the outbreak of the

European war. On August 4, 1914, Congress hastily passed an amendment that liberalized its

terms. Key provisions were that the limit on the emergency currency that could be created was

raised from $500 million to $1 billion and the tax rate on it was reduced. Unlike the Panic of 1907,

this time the Treasury was prepared. National banks would ameliorate the risk of a potentially

crippling monetary stringency in 1914 through the timely infusion of emergency currency. Other

actions were taken as well, among them closing the Stock Exchange until December 1914 and

expanding use of New York clearing-house loan certificates (Kane, 1922, p. 446-447).

National Banking Associations

Treasury officials were prescient enough as the Aldrich-Vreeland Act was being drafted to

comprehend that a serious emergency would overwhelm Treasury’s ability to manage a solution.

Accordingly, the act brought the national banks into the equation with a broader role than they

played in their ordinary national bank note issuances.

Two means were made available for national bankers to obtain emergency currency. The

preferred was to join a regional National Currency Association, which had the authority to accept

from the bank a broad range of financial instruments to back its emergency currency. The

association would vet the quality of the security deposit and hold it in trust for the United States.

The other option was for an individual bank to deposit non-Federal bonds directly with the U.S.

Treasurer.

In the end, less than $1 million of the $386 million in emergency currency was backed by

individual bank deposits with the U.S. Treasurer (Treasury, 1915, p. 577). The heavy lifting was

accomplished through the regional associations.

Several national currency associations were formed in 1908, but they were inactive owing

to lack of need. By January 1914, only 21 had been organized. However, as European tensions

intensified, their number ballooned to 45. Forty-one ultimately applied for emergency currency on

behalf of their members. Nine states had no representation; specifically, Maine, Vermont, Rhode

Island, Delaware, South Dakota, Montana, Wyoming, Idaho and Nevada. (Williams, 1915, p. 45).

Out of a national total of 7,578 national banks 2,197 had association memberships, of

which 1,359 received emergency currency. (Williams, 1914, p. 62; Treasury,1915, p. 531).

Other Securities

The following types of securities were permitted to back the emergency currency as

specified in regulations promulgated by the Treasury Department: commercial paper up to 75% of

cash value; state, city, town, county or other municipal bonds up to 85% of value; miscellaneous

securities up to 75% of value; and warehouse receipts up to 75% of value (Treasury, 1915, p. 578).

Warehouse receipts were very important to southern bankers who carried large loans on

cotton and tobacco. The southern economy would have been at significant risk had the Treasury

not made provisions for the bankers to back emergency currency with warehouse receipts even

though they ultimately represented only $6 million in emergency currency issues (Treasury, 1914,

p. 531).

Treasury Secretary William McAdoo issued the following statement on August 27, 1914.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

162

Figure 4. The national banks had to formally apply to Treasury to form a national currency

association. Above is part of the first page of the certificate signed by the presidents of the national

banks joining the Twin Cities, Minnesota, association. The associations were responsible for

verifying the value of the “other securities” placed on deposit with them for emergency circulation.

BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

163

Among the eligible securities to be used as a basis for the issue of currency I have decided to

accept from national banks, through their respective national currency associations, notes secured

by warehouse receipts for cotton or tobacco having not more than four months to run, at 75 per

cent of their face value. * * * This plan ought to enable the farmers to pick and market the cotton

crop if the bankers, merchants, and cotton manufacturers will cooperate with each other and with

the farmers, and will avail of the relief offered by the Treasury within reasonable limits. Such

cooperation is earnestly urged upon all these interests. (Treasury, 1914, p. 11).

Emergency Currency Design Changes

It is crucial to recognize at the outset that the Aldrich-Vreeland Act was introducing a new

class of national bank notes that were secured by financial instruments that were classified as

inferior to United States bonds. As such, Section 11 of the act required that the notes be redesigned

to incorporate language to this effect as follows.

In order to furnish suitable notes for circulation, the Comptroller of the Currency shall, under the

direction of the Secretary of the Treasury, cause plates and dies to be engraved * * *,and shall

have printed therefrom, and numbered, such quantities of circulating notes, in blank of the

denominations of five dollars, ten dollars, twenty dollar, fifty dollars, one hundred dollars, five

hundred dollar, one thousand dollars, and ten thousand dollars. * * * Such notes shall state upon

their face that they are secured by United States bonds or other securities.

Then-Secretary of the Treasury George Cortelou also instructed the BEP to alter the back

designs to further differentiate the notes. Thus, were born the Series of 1882 and Series of 1902

designs known to numismatists as date backs, because they respectively carried “1882-1908” or

“1902-1908” boldly on their backs (Treasury, 1908, p. 45-46).

Furthermore, the act required that stocks of the emergency notes be printed for every

national bank so they could be available on short notice, the following also from Section 11.

The Comptroller of the Currency * * * shall as soon as practicable cause to be prepared circulating

notes * * * equal to fifty per centum of the capital stock of each national banking association.

However, there was no way to predict which national banks would subscribe for

Figure 5. Cotton warehouse receipts were acceptable “other securities” that could be used as backing

for emergency currency. These were of particular importance to the southern currency associations.

This is the top part of a warehouse receipt widely used by Texas growers. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

164

emergency currency. Consequently, all the issuing banks received the new currency whether the

bankers subscribed for it or not. The legality of allowing the use of the new currency for all banks

was justified by acknowledging that if the new notes were issued from banks solely with

conventional United States bond backing, no harm would be inflicted on the note holder because

that backing was superior to the “or other securities” specified on the notes (Malburn, Mar 12,

1915). This view also dispensed with the practical problems associated with simultaneously

issuing two different varieties of notes to the same bank, one for their U.S. bond-secured notes and

the other for their “or other securities” notes.

The crash printing of the required stockpile of date notes placed an enormous burden on

the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. Nearly 10,000 face plates had to be altered to carry the “or

other securities” clause. New back plates of the date back designs had to be created and made for

the Series of 1882. Dates had to be added to existing Series of 1902 back plates as well as new

back plates that were made. In all, the Bureau turned out half a billion dollars’ worth of date backs

to satisfy this requirement in fiscal year 1909 (Ralph, 1909, p. 4). This volume was produced on

top of the quarter billion-dollar normal printing of national bank notes during that period.

Consequently, the volume of national bank notes printed during fiscal year 1909 tripled over 1908.

Protocol 1: Phasing-in the Date Back Notes

“The Comptroller of the Currency may issue national bank notes of the present form until

plates can be prepared and circulating notes issued. * * * That in no event shall bank notes

of the present form be issued to any bank as additional circulation provided for by this Act”

(Statutes, AV Act, Section 11).

The first date back Series of 1882 and 1902 notes were delivered to the Comptroller of the

Currency’s office from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on August 1 and June 15, 1908,

respectively. The last printings of the predecessor Series of 1882 brown backs and 1902 red seals

arrived on March 23, 1909 and December 15, 1908, respectively (Huntoon, chapter E1).

Following protocol, the Comptroller’s office continued to issue the 1882 brown back and

1902 red seals to the banks until those stocks ran out unless the bank subscribed for emergency

currency. During that era, the Comptroller’s stock of sheets used to replace worn notes withdrawn

from circulation typically averaged about a years’ worth of notes. Consequently, for the majority

of banks, their stock of the old variety was depleted before the end of 1909. Of course, the dates

of depletion varied between the banks.

Similarly, the dates of depletion of the different sheet combinations for a given bank that

used more than one combination also varied. A good example is from The Stock Growers National

Bank of Cheyenne, Wyoming, charter 2652. The last 5-5-5-5 and 10-10-10-20 brown back sheets

were sent to the bank on February 15, 1909 and June 25, 1908 respectively; the first of the 1882

date backs on February 15, 1909 and October 19. 1908. Between June 1908 and February 1909,

shipments to the bank consisted of a mix of 1882 5-5-5-5 brown back and 1882 date back 10-10-

10-20 sheets, sometimes in the same shipment. (CofC, 1863-1935).

Important in this context is that the first draw for emergency currency occurred on August

4, 1914. No banks have been identified for which stocks of 1882 brown backs or 1902 red seals

lasted that long. If such cases do exist, the changeover to the date backs would have occurred with

the first shipment of emergency currency to the bank as per protocol.

A factual irony is that all the date back notes that entered circulation between 1908 and

August 1914 were 100% U.S. bond-secured notes no different in legal standing than the Series of

1882 brown backs and Series 1902 red seals that they succeeded.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

165

The $500,000,000 Stockpile

The half billion dollars’ worth of Series of 1882 and 1902 date back notes printed to create

the stockpile of emergency currency deserves attention. The initial stockpile consisted of

individual printings for each issuing national bank amounting to 50 percent of their capital stock.

It was printed in fiscal year 1909. At that time, the sheets were delivered to the Comptroller of the

Currency’s office in Washington, DC where the printings were added in sequence to the remaining

pre-date back varieties maintained for each bank.

This was not a static inventory of currency locked away in some Treasury vault. Rather, it

was a fluid working trove that was continuously tapped and replenished. The inventories for the

individual banks continued to be drawn down in sequential order as notes were needed to replace

worn notes withdrawn from circulation and for routine increases of bank circulation. Inventories

also were created for new banks.

The Comptroller’s clerks continually ordered new printings that were appended to the

bank inventories to offset the draws in order to maintain the dollar value of the stockpile. Those

demands totaled an average of $472 million per fiscal year during fiscal years 1910 through 1914.

This meant that the half billion-dollar stockpile was in fact almost turning over each fiscal year.

Figure 6. Vault #10, one of the Comptroller’s Issue Division vaults. National bank note sheets

totaled $250 million in the vault at the time of this 1914 photo. The sheets are wrapped in

heavy brown paper for protection. Charter numbers are penciled on the ends of the packages

for ease of retrieval by the vault clerks. Orders of emergency currency from August to

October 1914 packed vaults like this unless the sheets were shipped directly to a

subtreasuries. Library of Congress photo LCN 2016852709.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

166

Consequently, when the stockpile was called upon in August 1914, most of the notes in it had been

printed within fiscal year 1914, not 1909.

One of the issues faced by Treasury was that its half billion-dollar stockpile in August 1914

was heavily weighted with inventories for 6,219 banks that didn’t subscribe for emergency

currency. The primary users of it among the 1,363 banks that did subscribe were big city banks.

However, the part of the stockpile carried for the large banks proved to be sorely inadequate.

Consequently, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing was continually pressed to execute rush

orders to cover those deficiencies, which ultimately totaled about $300 million. Those rush orders

amounted to 3/5ths of the value of the stockpile.

Protocol 2: Available on Short Notice

“[Date back] notes to be deposited in the Treasury or in the subtreasury of the United States

nearest the place of business of each association, and to be held for such association, subject

to the order of the Comptroller of the Currency, for their delivery” (Statutes, AV Act, Section

11).

Traditionally, printings of national bank notes were received by and stored at the

Comptroller of the Currency’s vaults in the main Treasury building in Washington, DC. Shipments

to the banks were made from there as required. The framers of the Aldrich-Vreeland Act wanted to

speed delivery of the emergency currency to the banks. To cut transit time, they wanted the stocks

to be moved as close to the banks as possible, but still held under the control of the Treasury until

requisitioned. Storage of the notes at the existing subtreasuries around the country satisfied this

objective.

The Treasury Department operated nine regional subtreasuries to help it issue and redeem

currency. They were located in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Cincinnati, Chicago,

St. Louis, New Orleans and San Francisco. Each was administered by an Assistant Treasurer

(Treasury, 1920, p. 167-169).

The hastily printed half billion dollars’ worth of date backs during fiscal year 1909 were

delivered to the Comptroller’s office. There is no evidence that any of this stockpile was distributed

to the subtreasuries before 1914. Treasury officials did not violate the Aldrich-Vreeland Act by

not immediately moving the date backs to the subtreasuries. Instead, they used a technicality

afforded by a careful reading of the act to delay doing so. Specifically, the language in the act was

“to be deposited in the Treasury or in the subtreasury” (Statutes, AV Act, Section 9). The operative

word was “or.” The $500,000,000 in the Comptroller’s vaults in Washington was in the Treasury

so it satisfied the language of the act.

The Treasury mobilized as war clouds gathered over Europe. A Treasury press release on

July 31, 1914 advised “We are keeping in touch with the situation. The Treasury Department will

help as far as it legitimately may in New York or any other part of the country where it becomes

apparent assistance is needed. * * * It must be remembered that there is in the Treasury [in

Washington], printed and ready for issue, $500,000,000 of currency, which the banks can get upon

application under law” (Treasury, 1914, p. 2; NYT, Aug 1, 1914). Pre-staging sheets in the

subtreasuries did not begin until August 4th...

On August 3rd Treasury Assistant Secretaries Charles Sumner Hamlin and William

Peabody Malburn, as well as Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams were on duty at

the New York subtreasury to emphasize that the Treasury was ready to assist the banks with

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

167

emergency currency (Treasury, 1914, p. 3).

On August 4 some $40-$50 million was delivered to the New York subtreasury in a caravan

of 20 large mail trucks as crowds gathered to watch (NYT, Aug 4, 1914). The first emergency issues

went out immediately from the New York subtreasury.

From August 4 forward, subscriptions for the emergency currency were hastily sent to the

banks from every source possible. This procedure was new to the bookkeepers in the Comptroller’s

office. They were simultaneously logging out shipments to a given bank from the subtreasuries as well

as from their own vault in Washington as fast as they received new printings from the Bureau of

Engraving and Printing.

The exigencies of the times required the Bookkeeping Division in the Comptroller’s Office

to adapt to the chaos. As shown on Figure 7, the task of tracking shipments of large amounts of

emergency currency was daunting and anything but orderly. Bookkeeping staff worked overtime

to keep up. They not only had to record the issuances of emergency currency from the subtreasuries

and their own office, but also shipments from the issue division that covered replacements for

worn notes withdrawn from circulation.

Under ordinary circumstances, the Comptroller’s Issue Division vault personnel

maintained the issuance of national currency within their ledgers in bank sheet serial number order

for each sheet combination used by the bank. That tidiness went out the window with the

Figure 7. National Currency and Bond ledger page showing the massive emergency issues (black ink

entries at left) to The Merchants National Bank of St. Paul, charter 2020. The clerks offen marked

the emergency currency issues with the notation “EC” (see arrow), although this practice was not

universal. The bond ledger at top shows that the bank deposited miscellaneous securities on August

12 and September 30 totaling $1.67 million dollars in order to receive emergency currency. The red

ink entries at right are pre-war redemptions without reissue during a pre-war period when the bond-

secured circulation had been cut from from $1,000,000 in 1912 to $275,000 in 1913. The emergency

infusion ballooned the circulation to over $1 million in 1914, after which it settled to $375,000 by

1915. CofC (1863-1935).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

168

emergency currency. New to them was that the sheets were no longer going out in numerical order,

which made their ledgers messy and harder to prove. Heavy reliance was made on dollar totals

rather than sheet serial numbers. In some cases, desperate clerks drew arrows connecting the

entries with consecutive serial numbers to demonstrate that all the serial numbers had in fact been

delivered during some period of interest (CofC, 1914).

The poor clerks were pushed into overdrive. As one example, the Bureau of Engraving and

Printing ordinarily delivered new sheets to the Comptroller’s office once or twice a month for The

Merchants National Bank of St. Paul, Minnesota. When those bankers applied for emergency

currency at the start of the war, the BEP was making up to three shipments a day to the

Comptroller’s office for the bank. The daily highpoint was September 29th when four separate

deliveries of $5 arrived, 4,000 sheets in all. Multiply this by the needs of hundreds of rush orders

for subscribing banks per day and you get the picture.

Many clerks resorted to helpful short-hand notations such as adding “EC” for emergency

currency from Washington or “EC–Asst Treasurer” from a subtreasury. Some also flagged the

shipments containing replacements for worn notes from the bank’s bond secured circulation with

the notation “US Bonds.” The clerks came back later to make recapitulation entries on the ledgers

for the larger banks to prove that all the available sheets had been found and shipped from both

Washington and the subtreasuries (CofC, 1914-5).

Protocol 3: Returned and Redeposited Sheets

Sheets of national bank notes returned to the Treasury to redeem emergency currency by the

issuing bank could be redeposited in the Comptroller of the Currency’s inventory for reissue

to the bank (Treasury policy adopted in November, 1915).

Prior to enactment of the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, national bankers desiring to redeem part

or all of their circulation were required to deposit lawful money with the U.S. Treasurer that was

placed in a retirement fund managed by his office to redeem a like amount of the bank’s notes from

circulation. At the time the Aldrich-Vreeland Act was passed, Congress had defined through past

legislation that lawful money consisted of gold coin, legal tender notes, silver certificates and gold

certificates. National bank notes were not considered lawful money under national banking law.

However, a critical provision in Section 10 of the Aldrich-Vreeland Act authorized the use

of national bank notes as well as lawful money for the redemption of the emergency currency as

follows.

Any national banking association desiring to withdraw any of its circulating notes, secured by the

deposit of securities other than bonds of the United States, may make such withdrawals at any

time in like manner and effect by the deposit of lawful money or national bank notes with the

Treasurer of the United States.

This was an extremely important provision. Without it, if banks could only use lawful

money to retire their emergency notes, the massive withdrawal of lawful money from circulation

would worsen the very crises the Aldrich-Vreeland Act was supposed to cure.

It was roughly the third week of October 1914 when the banks began to redeem their

emergency currency in large quantities, no doubt spurred on by a looming accounting of the first

quarterly tax installments due on the notes. Using gold coin and gold certificates, silver certificates,

legal tender notes, and increasing numbers of national bank notes, the retirement deposits grew

larger almost daily into November and December, often totaling several million dollars per day

(BPD, 1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

169

Under Section 10 of the Aldrich-Vreeland Act, the national bank notes deposited to retire

a bank’s emergency circulation could be the bank’s own notes or notes of any other national bank.

Deposits could be sent either via the local subtreasury or directly to the National Bank Redemption

Agency in Washington. In due course, as bankers retired their emergency currency circulations,

many sent back unused sheets of their own emergency currency.

Ordinarily, when the circulation of a bank was being retired in whole or part, retired notes

were canceled and destroyed after receipt by the National Bank Redemption Agency. However,

after the unused sheets started to come back in large numbers, conscientious Treasury operatives

deemed the practice of canceling the sheets as wasteful so Treasury officials adopted a policy

whereby the unused sheets could be redeposited with the Comptroller for future reissue.

Figure 8. A Treasury daily redemption report listing banks that were returning

sheets of their own emergency currency that were being redeposited for reissue

with the Comptroller of the Currency. The redeposited sheets disrupted the tidy

serial number tracking procedure normally used by the vault clerks and

bookkeepers. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

170

I was unable to find a specific Treasury directive addressing the redeposit of redeemed

sheets. However, a review of multiple ledgers covering hundreds of banks from summer 1914 to

summer 1915 revealed the earliest redeposits began November 27, 1914 and the latest found was

on April 10, 1915. That particular April 10th redeposit consisted of $11,050 in sheets for The City

National Bank of Paducah, Kentucky, charter 2093.

The redeposited sheets were treated in the National Currency and Bond Ledgers identically

as new currency received from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing except, they were logged in

by dollar value because the sheets usually were not in serial number order. They generally, but not

universally, became the next sheets issued from the vault inventory until consumed. Virtually all

the redeposited sheets reappeared as bond-secured notes.

In one example, The Farmers and Mechanics National Bank of Georgetown, DC, charter

1928, maintained a bond-secured circulation of $250,000 before the war. In mid-August 1914, the

bankers deposited $25,000 of “other securities” and received 500 sheets of emergency currency in

the form of 10-10-10-20 Series of 1902 date back sheets. On November 28, they returned all 500

sheets to retire their emergency currency.

Starting December 7, 1914, and continuing through January 22, 1915, shipments from the

Issue Division to replace worn notes for the bank’s bond-secured circulation consisted of the 500

redeposited sheets. They were the first to go after being redeposited. See Figure 9.

Figure 9. The right arrow points to the redemption entry where The Farmers & Merchants National

Bank, Georgetown, D.C., returned its entire emergency currency issue of $25,000 on November 28,

1914. The arrow at left shows the same sheets being sent back to the bank in December and January,

this time as regular bond-backed date back notes. The tell-tale sign is that the reissue entries at left

are devoid of serial numbers because the sheets often were not in serial number order and also to

avoid recording the same serial numbers twice. CofC 1863-1935).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

171

The redeposits for a few banks outlived the large note era without being fully consumed as

reissues.

Victory Lap

As the European war and banking crisis crept to America’s doorstep, the Aldrich-Vreeland

Act as amended in 1913 and 1914 proved to be an example of the government getting things right.

A repeat of the Panic of 1907 was averted. Whatever the impact of the coming war, widespread

bank failures and financial panic in the United States was not a part of it.

Starting in August 1914 and continuing through Spring 1915, Malburn mobilized the

Treasury and subtreasuries to do meticulous daily reporting on the emergency currency being

issued and then being retired (BPD, 1914-1915). Although it was labor intensive to do so, Malburn

wanted to closely track how the currency was being used and to ensure it was being redeemed as

soon as it wasn’t needed.

McAdoo and Malburn knew the Wilson Administration’s political opponents would

pounce the moment they could allege there were unnecessary inflationary notes swelling the

nation’s money supply. As it turned out, the higher tax rates on the emergency currency worked

exactly as designed to force the prompt redemption of the unneeded emergency currency.

Some bankers returned most or all their emergency currency before it was circulated.

Simply having it in their vaults and teller cages was enough to quell the angst of their depositors.

The needed liquidity was on hand for short-term commercial loans including loans needed to

Figure 10. Treasurer of the U.S. John Burke at left, Treasury Assistant Secretary William P.

Malburn at right. Malburn had the significant policy and operational responsibility for emergency

currency issue and redemption. He was visible to the public, press, and banking community

throughout the crisis. Burke’s National Bank Redemption Agency shouldered the enormous

redemption workload with the subtreasury offices. Library of Congress photoh LCN 2016853719.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

172

facilitate agricultural harvests. The economy had in-hand the money it needed to jumpstart our

preparations for the coming war.

The news media, particularly the financial press, tracked the emergency currency situation

closely. Malburn must have been gratified with a February New York Times headline that declared

“Emergency Notes All In; Books Close” for the National Currency Association of New York

(NYT, Feb 10, 1915). By mid-February less than 10 per cent of the total emergency currency

issued since August remained outstanding (NYT, Feb 19, 1915).

The conservative Commercial & Financial Chronicle opined in February 1915 that the

Aldrich-Vreeland Act, set to expire on June 30, 1915, should be extended for “another year or two,

and possibly indefinitely. * * * Thus the Aldrich-Vreeland law provides the means for much more

effective action than the Federal Reserve Law, and also on a larger scale” (Chronicle, Feb 13,

1915). The Chronicle reasoned that since the Aldrich-Vreeland Act permitted a broader range of

“other securities” as collateral for emergency notes than permitted with Federal Reserve notes, the

Aldrich-Vreeland notes would be more effective. Treasury and Congress differed, however, and

the Aldrich-Vreeland Act expired at the end of June. Future crises would be handled by the Federal

Reserve system.

By July 1, 1915, all but approximately $172,000 from a failed bank in Pennsylvania of the

$386 million in emergency currency had been retired.

Malburn himself had the last word on the emergency issues, writing the following in 1915

after more than 90 percent of the notes had been retired.

It is evident that any fears that have been entertained that the large amount of additional currency

put in circulation after August 1, 1914, would unduly inflate the circulation, and would not be

promptly retired, may be dismissed. * * * Without doubt the issuance of this currency enabled the

country to pass through the troublous times succeeding the outbreak of the European war last

Summer, with much less strain than has attended financial disturbances of less severity in the past,

and it is shown how advantageously the Federal reserve notes may be used in the future.” (Melburn,

February 18, 1915).

Acknowledgments

The Bureau of Public Debt documents that formed the basis for this article are from the

Retired Currency of 1914-1915 files, Record Group 53, Entry 545 housed at the National Archives

at College Park, Maryland, full citation below. Peter Huntoon provided the delivery data for the

Stock Growers National Bank of Cheyenne and made valuable manuscript suggestions. Fred

Maples provided timely assistance pertaining to Maryland national bank ledger pages.

Sources

Bureau of the Public Debt, 1914-1915, Records regarding destruction of retired currency: Record Group 53, Entry

545, file 1 – Reports of Deposits Made on Account Retirement Additional Circulation 1914, and file 2 – National

Currency Emergency Association - Emergency (53/450/53/21/3 boxes 1 through 3). U.S. National Archives,

College Park, MD.

Commercial & Financial Chronicle, Feb 13, 1915, The Financial Situation: William B. Dana Company, New York,

NY. v. 100, p. 500.

Comptroller of the Currency, 1863-1935, Division of Issues, National Currency and Bond Ledgers: Record Group

101, Entry UD-14, National Archives, College Park, MD.

Encyclopedia of U.S. National Bank Notes: Society of Paper Money Collectors:

https://spmcsponsor.mywikis.wiki/w/index.php?title=Encyclopedia_of_U.S._National_Bank_Notes&oldid=121

Hepburn, A. Barton, 1915, A History of the Currency in the United States. The McMillan Company, New York, NY,

573 p.

Huntoon, Peter W. The Aldrich-Vreeland Act and Series of 1882 and 1902 Date Back National Bank Notes: Huntoon-

Shiva Encyclopedia of U.S. National Bank Notes, chapter E1. (See Encyclopedia citation above).

Huntoon, Peter W. The National Bank Note Series 1882 and 1902 Post-Date Back Transition, Huntoon-Shiva

Encyclopedia of U.S. National Bank Notes, chapter E2. (See Encyclopedia citation above).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

173

Kane, Thomas P., 1922, The Romance and Tragedy of Banking: The Bankers Publishing Company, New York, NY,

549 p.

Malburn, William P., February 18, 1915, Assistant Secretary of the Treasury press release pertaining to redemption

of emergency currency.

Malburn, William P., March 12, 1915, Letter from Assistant Secretary of the Treasury to Joseph E. Ralph, Director,

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, authorizing that “or other securities” plates may be used until exhausted:

Bureau of the Public Debt, Record Group 53, 450/54/1/5, box 10, file K712, National Archives, College Park,

MD.

Meltzer, Allan H. A., 2003, History of the Federal Reserve, Volume 1: 1913-1951: University of Chicago Press,

Chicago, IL.

New York Times, July 28, 1914, Run on Berlin Banks: p.2; August 1, 1914, Washington Alert to Aid Situation: p. 5;

August 4, 1914, Provision for a Billion More Money – Emergency Currency Here: p. 4; August 7, 1914, Armored

Cruiser Sails with Gold for Stranded Americans: p. 4; August 28, 1914, M’Adoo Draws Pan for Moving Cotton,

p. 11; February 10, 1915 Emergency Notes All In; Books Close: p. 15; Retire Emergency Money, February 19,

1915: p. 13. New York Times, New York, NY.

Ralph, Joseph E., 1909, Annual Report of the Director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing for the Fiscal Year

Ending June 30, 1909: Government Printing Office, Washington DC.

Statutes, U.S.: Aldrich-Vreeland Act, May 30, 1908, An Act to Amend the National Banking Laws: U.S. Statutes,

P.L. 60-169, 35 Stat 546, 60th Congress, 1stt Session; Federal Reserve Act of December 23,1913, P.L. 63-43,

63rd Congress; & Federal Reserve Act Amendment, August 4, 1914, P.L. 63-163, 13 Stat. 682, 63rd Congress, 2

Session.

Treasury, U.S., 1908, 1914, 1915, & 1920, Annual Reports of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the

Finances: Government Printing Office, Washington, DC

Williams, John Skelton, 1914 & 1915, Annual Reports of the Comptroller of the Currency: Government Printing

Office, Washington, DC.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

174

Aldrich-Vreeland Emergency Currency

Photo Gallery

Figures A. While Treasury’s use of the Alrich-Vreeland Act emergency currency successfully

prevented Europe’s bank panics spreading to the U.S., there were isolated incidents. Here, the

German Savings Bank in New York City has a run by its depositors on August 3, 1914. American

citizens of German decent and recent immigrants were closely watching the banking panic in their

former home country. In this case, the catgion spread, but fortunately such incidents in the U.S. were

rare. Hoarding was commonplace, but bank runs were not, in large part due to Treasury and the

national banks having ample emergency currency supplies available. Photos: CNN top left; Google

top right; Library of Congress LCN 2014696884 bottom.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

175

Figure B. As the war broke out in Europe, hundreds of U.S. bankers sought to quickly join National

Currency Associations. Worried about the time it would take banks to apply individually for

membership, Treasury Assistant Secretary Charles Sumner Hamlin stepped in to expedite the

process and reassure bankers seeking emergency currency that it would not be delayed. This

telegram from the National Currency Association of Dallas expresses the Association’s delight at

being told by Treasury to open its membership to all sound national banks in the district. BPD (1914-

1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

176

Figures C. The interest in obtaining emergency currency extended beyond

national banks. At top, A.J. Moore, the president of the First State Bank of

Bonham, Texas, sought to join the Dallas National Currency Association. The

Association sought Treasury’s ruling on whether that was permissible.

Assistant Secretary Malburn replied at bottom, saying to Moore that

memberships would not be extended to state banks and trust companies.

BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

177

Figure D. National banks subscribed for their emergency currency via the National Currency

Assocation to which they belonged. Banks first placed “other securities” on deposit with their

Association. Upon the Association validating the value of the securities, the Association would

place an order for emergency currency on behalf of the bank with the Comptroller’s office using

the form above. Note the use of the formal term “additional circulation” rather than “emergency

currency” on the form. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

178

Figure E. Treasury officials closely tracked the National Currency Associations and their

banks applying for emergency currency. Above is page 1 of a long September 10, 1914 report

to Treasury senior officials listing subscriptions for emergency currency, the amounts, and

deliveries. The “ST” notation for The Kensington National Bank of Philadelphia means the

notes were delivered from the Philadelphia subtreasury, not the Comptroller’s Issue Division

in Washington. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

179

Figure F. Another Treasury daily report of emergency currency requests and deliveries. This report

shows multiple deliveries from the regional subtreasuries. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

180

Figure G Enterprise National Bank of Laurens, South Carolina, was one of a handful of

banks that issued only emergency currency based on research by Peter Huntoon and Mark

Drengson. The bankers never reported a taxable circulation during the ten the ten year life

of the bank. They ordered emergency currency in 1914 but retired it before having to report

it. Huntoon and Drengson have identified about a dozen banks that similarly issued only

emergency currencys. Heritage Auctions archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

181

Figures H. The emergency currency was shorted lived. The first deliveries were on August 4, 1914,

and the last on February 12, 1915. In the third week of October banks began to retire their emergency

circulations in enormous amounts each day. Subtreasury offices sent telegrams to the Treasury

Department in Washington to report the daily redemption deposits. The telegrams above date from

November and December, 1914. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

182

Figure I. Section 10 of the Aldreich-Vreeland Act allowed emergency circulation to be retired

through payment of lawful money or national bank notes. Previously, national bank

circulations could not be retired by deposit of national bank notes. Some subtreasury officers

and many national bankers were unfamiliar with the provision, so when some banks started to

send in national bank notes the subtreasury officers questioned the practice. The telegram

above, from October 21, 1914, is one such questioning telegram. BPD (1914-1915).

Figure J. In reply to the questions about the legality of accepting national bank notes to retire

emergency currency, Treasury Assistant Secretary William P. Malburn cabled the subtreary

offices on October 23, 1914 to hold such submissions until further guidance could be issued.

BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

183

Figure K. Malburn sent instructions on October 29, 1914 to the subtreasuries making it clear that

national bank notes were to be accepted for retirement of emergency currency. The example above

went to the Assistant Treasurer at Baltimore, Maryland. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

184

Figure L. Depsite his October 29 guidance to subtreasuries to accept national

bank notes to retire emergency currency, several days later he was still

telegramming certain offices confirming the instructions. BPD (1914-1915).

Figure M. The notice of receipt for The Hanover National Bank of New York

is a good example of the enormous value of national bank notes being used to

retire emergency currency, Malburn’s signature on this document reveals his

personal involvement in the redemptions process. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

185

Figure N. First page of a long daily Treasury report sent to Treasury Secretary

William G. McAdoo from Treasurer John Burke listing deposits to retire emergency

currency and the types of money used for the deposits. Imagine $500,000 in gold coins

in a single deposit. The page is a good example of the volume and variety of deposits

used to quickly retire the emergency notes. See column on right above. BPD (1914-

1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

186

Figures O. It was not only large city banks that utilized emergency notes. Here are

two small town examples. These national banks in Grapevine, Texas, and Roswell,

New Mexico, kept their emergency circulations going into 1915, retiring them

respectively in January and June 1915. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

187

Figure P. Redemption accounting form used by the National Bank Redemption Agency. One of

the many complexities in the redemption process was determining if bank notes received for

redemption were (1) bond-securedd redemptions requiring replacement notes to be sent out, (2)

retirements of notes from out-of-business banks, (3) banks reducing their bond-secured

circulations, or (4) banks retiring their emergency currency. The arrow points to the column

where emergency currency retirements were recorded. Once notes were sorted by bank and

recorded on the above form, the redeemed notes were sent to the Comptroller of the Currency’s

Redemption Division for a second confirmation count. Notice that the National Bank Redemption

Agency sorting was done alphabetically by the name of the towns on the notes, not charter

number. General Records of the Department of the Treasury.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

188

Figure Q. By late fall 1914, millions of unissued sheets of emergency currency remained in the

regional subtreasuries. The original cost of shipping the sheets to the subtreasuries had been billed

to the banks, but Comptroller of the Currency John Skelton Williams saw a backlash coming if the

banks had to pay to ship unrequested sheets back to Washington. Treasury Assistant Secretary

Malburn put the question to his departmental attorneys in the Office of the Comptroller of the

Treasury. He received the reply he and O’Connor were seeking, namely that it was permissible

under the Adrich-Vreeland Act for the government to pay to ship the sheets back to the Issue

Division in Washington. BPD (1914-1915).

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

189

Figure R. The full story behind this $50 Series of 1882 date back note is one that makes national

bank note collecting so enticing. The National Marine Bank of Baltimore nearly doubled its

circulation in 1914 using “other securities” as collateral when the war broke out. The BEP went into

overdrive to deliver additional vault stock for the bank with one thousand sheets of 50-50-50-100

notes being delivered to the Comptroller’s Issue Division on August 17, 1914 bearing bank serials

301 to 1300. That delivery included this note with bank serial 500. However, the $50 and $100

emergency currency issued to the bank ended with the sheet 405 on September 1. The rest of its

emergency currency consisted of $5, $10 and $20 notes, the last of which were sent November 21st.

The bankers then retired all their emergency circulation between November 23, 1914 and January

23, 1915. Sheet 500 containing this note was sent to the bank July 12, 1915 as a bond-secured note.

Heritage Auctions archives photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

190

Postscript

Treasury Entry Pivots from Emergency Currency to

Financing America’s into the War

Figure S. The Aldrich-Vreeland emergency currency allowed the Treasury in 1914 and 1915 to

avoid the banking panics that plagued Europe as war broke out. Meanwhile, President Woodrow

Wilson sought to keep America out of the war. By 1917, Wilson and Congress knew entering the

war was inevitable. Above, the American Rainbow Division enters St. Nazaire, France, November

3, 1917. The job of the U.S. Treasury shifted from emergency currency to financing the U.S. war

effort through Liberty Loans. Library of Congress photo LCN 2014706754.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

191

Figures T. Treasury’s work to finance the American war effort was essential

to the country’s success. Treasury Secretary McAdoo was committed to

financing the war through borrowing, not printing greenbacks. The Liberty

Loans and later Victory Loan effort were the result. At top, a Liberty Bond

poster adorns the corner sidewalk outside the Treasury Department in 1917.

At bottom, Treasury workers and Army representatives prepare for a bond

drive on Treasury’s steps by displaying captured German helmets. Library

of Congress photos LCN 2016868455 and LCN 2016819648.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

192

Figures U. Liberty Loan Posters were part of a massive advertising campaign that

helped raise the money to financed the American war effort. At top, a poster that

dispayed the Treasury Department itself. Library of Congress photos LCN

2001695789, LCN 00652903 and LCN 00652888.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

193

Figure V. First Liberty Loan of 1917 $100 4 percent coupon bond. The Bureau of Printing and

Engraving went from producing millions of sheets of emergency currency to cranking out millions of

Liberty Loan bonds. Herbstman Collection of American Finance photo.

SPMC.org * Paper Money *May/June 2024 * Whole No. 351

194

Shop Live 24/7

Scan for $10 off your first purchase

whatnot.com

Lyn Knight Currency Auct ions

If you are buying notes...

You’ll find a spectacular selection of rare and unusual currency offered for

sale in each and every auction presented by Lyn Knight Currency

Auctions. Our auctions are conducted throughout the year on a quarterly

basis and each auction is supported by a beautiful “grand format” catalog,

featuring lavish descriptions and high quality photography of the lots.

Annual Catalog Subscription (4 catalogs) $50

Call today to order your subscription!

800-243-5211

If you are selling notes...

Lyn Knight Currency Auctions has handled virtually every great United

States currency rarity. We can sell all of your notes! Colonial Currency...

Obsolete Currency... Fractional Currency... Encased Postage... Confederate

Currency... United States Large and Small Size Currency... National Bank