Bringing Vignettes to Life

“All Benefactors of Man I Claim as My Brethren”: Henry D. Cogswell and his Fountains of Philanthropy

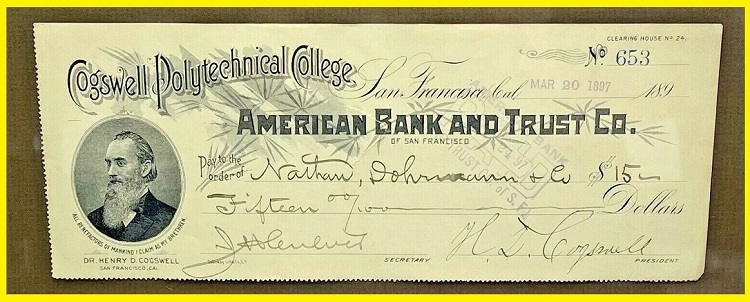

This 1897 check from the Cogswell Polytechnical College of San Francisco honored its founding benefactor with a three-quarter medallion portrait of Henry D. Cogswell (1820-1900), beneath which appears the inscription “All Benefactors of Mankind I Claim as my Brethren.” Cogswell not only funded the establishment of his eponymous school, but cultivated a reputation as a prominent San Francisco philanthropist throughout the second half of the 19th century. Arriving in that city from the East as a practicing dentist during the gold rush years, Cogswell quickly became wealthy through financial and real-estate speculation, which allowed him to retire and, with his wife Caroline, indulge in various civic-minded pursuits.

Although Cogswell Polytechnical and its successor institutions represent the longest lasting aspect of his philanthropic legacy, the dentist is better known historically for his more controversial campaign to finance the installation of temperance-themed public fountains in towns and cities throughout the United States. Cogswell’s theory, shared by other temperance activists of his time, was that readily-available supplies of cold, fresh water would dissuade people from imbibing alcoholic alternatives. Widely criticized for their grandiose bad taste, Cogswell’s fountains came under particular scorn because some of them incorporated statues rendered in the likeness of Cogswell himself.

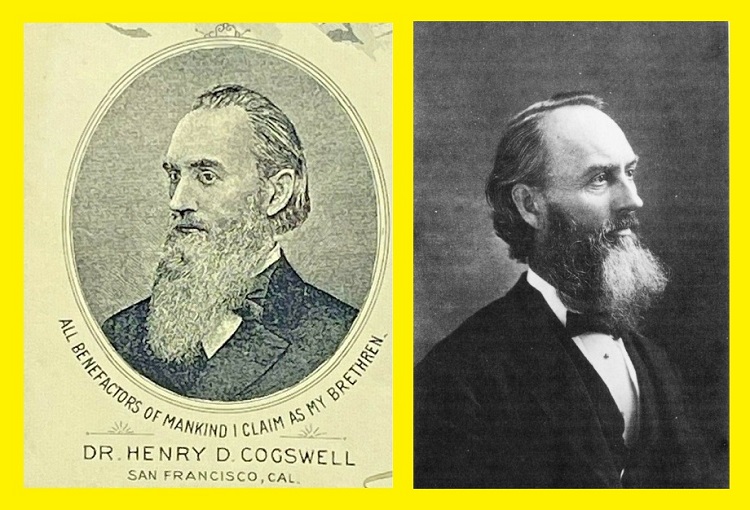

Left, check vignette enlarged. Right, photograph of Cogswell from about 1882 (from Moffatt 1992).

Dentist, Temperance Advocate, Philanthropist

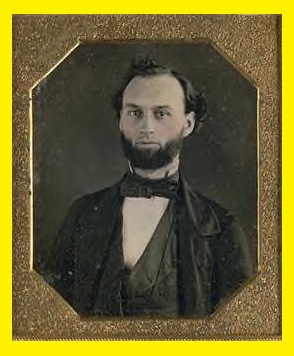

Henry Daniel Cogswell was born in Tolland, Connecticut in 1820 (possibly 1819). After an itinerant and somewhat rough adolescence that included stints as a mill worker and time in a poorhouse, Cogswell settled in Orwell, New York where, through his own effort and initiative he acquired sufficient education to work, by the standards of the time, as a dentist. By the 1840s he was apprenticing in Providence, Rhode Island, where he met his wife, Caroline Richards, in 1846. Not long after setting up his own practice in Pawtucket, Henry Cogswell and his brother James (also a dentist) repaired to California to participate in the gold rush.

Cogswell as a young man (Online Archive of California)

Although less well-known than figures like Samuel Brannan or Levi Strauss, Henry Cogswell belonged to that cohort of California-bound entrepreneurs who got rich not from mining gold, but from provisioning and servicing the booming extractive economy. After briefly operating his own mercantile establishment, Cogswell soon returned to dentistry (gold teeth proved to be fashionable accessories for the miners), with an office off San Francisco’s Portsmouth Square whose sidewalk advertisement proclaimed “the Sign of the Golden Tooth”.

One of the first dentists in California, Cogswell was an early adopter of chloroform as a dental anesthetic; he also had to his credit a patented technique for inserting dentures with a vacuum seal. Well-timed business and property speculations made Henry Cogswell a multi-millionaire by his mid-30s. After 1855 Cogswell retired from active dentistry, later transferring his practice to his brother James. Thereafter, he occupied himself with managing his financial interests, extensive travel with his wife Caroline throughout Europe and the Americas and, most of all, tending to his philanthropic projects, the most notorious being his scheme for installing temperance fountains.

Henry Cogswell was undeniably a generous individual, and not particularly given to miserliness in his personal life. Nonetheless, he displayed that characteristic foible of successful people who, believing that their good fortunes were due essentially to their own hard work, talents, or character and not to propitious circumstances (like being in the right place at the right time), take to exhorting others to follow in their meritorious footsteps. Moreover, running through the humble brag of his own bootstrap origins was a streak of genealogical vanity. Cogswell traced his lineage back to a 15th century English nobleman, Lord Humphrey Cogswell. Armed with this fact, the descendant incorporating his ancestor’s coat of arms into his possessions and even embossing it on his correspondence. In this way, Henry Cogswell could lay claim both to the Yankee virtues of the self-made man and to the social snobbery of noble lineage.

A temperance medallion from 1865, of unknown issue, with Cogswell's coat of arms on the reverse (Yesteryear Essentials).

In combination, these traits complicated Cogswell’s attempts to give away his money. His philanthropic projects entailed repeated and sometimes heavy-handed attempts to shape how the recipients of his generosity used his gifts. Not only did those gifts come with strings attached but, as in the case of his temperance fountain crusade, his insistence that recipients put up their own resources led many to reject his offers of largesse.

Although not affiliated with the organized temperance movement, Cogswell was a forceful advocate for sobriety on the grounds that alcohol led people astray from the capitalist virtues of industriousness and thrift. These views did not go over well in San Francisco, which at the time had a raucous saloon culture catering to ethnic populations that had no problem with the booze. In 1870, Cogswell and his wife embarked upon an extensive, four-year tour of Europe, where he became acquainted with the variety and ubiquity of public drinking fountains. Convinced that plentiful supplies of clean, cold drinking water would provide people with a healthy alternative to the saloon, upon returning home Cogswell devoted the next fifteen years to sponsoring the installation of temperance-themed fountains across the country.

Cogswell’s fountain crusade was not merely the eccentricity of a wealthy do-gooder. The ornamental drinking fountain as a vehicle of temperance propaganda was also promoted at this time by organizations like the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. In an era when potable water supplies could not be taken for granted and beer represented an uncontaminated alternative, publicly-available supplies of clean water took on added significance.

Nor were these small drinking fountains in the modern, utilitarian sense, but substantial installations that could draw on a variety of figurative motifs made available by Eastern commercial statuary companies and foundries through their trade catalogs. In addition, Cogswell’s fountains incorporated an ice-block refrigeration feature, patented by Cogswell himself, which promised to deliver chilled water to thirsty drinkers. One of Cogswell’s earliest fountain projects was in San Francisco, from 1879 (the first of eight he would donate to that city), and featured a statue of Benjamin Franklin that still stands to this day. Other, early recipients of Cogswell’s largesse included the Connecticut towns of his humble origins. In all, Cogswell sponsored about fifty such fountain installations around the country. While some towns and cities welcomed Cogswell’s offer, others demurred because of the terms Cogswell demanded for his donation. Municipalities not only had to pay for shipping, installation, and upkeep (including ice for their refrigeration), but were required to purchase accessories (not to mention have an adequate water supply to connect the fountain to in the first place).

In addition, many people simply found the fountains to be aesthetically unappealing—visually overbearing and excessively hortatory with their temperance sloganeering. About half of the fountains Cogswell sponsored featured a statue of an unnamed, bearded “silent orator” in a Prince Albert-style frock coat, his right hand outstretched, proffering a glass of water, his left holding a temperance pledge. Public scorn heightened when it became widely suspected that the statue was modelled on Cogswell himself. In the early 1880s, Cogswell engaged the Monumental Bronze Co. of Bridgeport, Connecticut to produce some two dozen of the cast statues based on a clay model created after a mid-life photograph of Cogswell. The Monumental Co. had pioneered the use of sand-casted zinc (commonly known as “white bronze”) as a vastly cheaper and quicker alternative to sculpted stone.

The blatant megalomania of Cogswell’s self-memorialization did not go over well with the fountains’ intended recipients. Officials in Washington, D.C., backtracked on their earlier acceptance of a Cogswell fountain once they realized who it depicted. Eventually, Cogswell and the city agreed on an alternative, a four-poster canopied mash-up involving a heron and entwined, scaly dolphins, an often-reviled fountain which, for many years, languished in front of a major D.C. liquor store. That the fountain exists to this day is thanks in part to the preservation efforts of the Cogswell Society, a late 20th-century drinking club in that city which playfully adopted the monument (and its donor’s) name. Boston’s fountain, placed on the Common in 1884, also featuring dolphins, was removed nine years later by popular revulsion. The episode led to the passage of state legislation in 1890 creating an Arts Commission that would henceforth vet proposed monuments in public places.

Most of Cogswell’s other installations around the country suffered the ravages of time, particularly as his gifts came with no provision for their upkeep. Those featuring the “silent orator” statute in Cogswell’s own likeness came in for particular abuse. One in Rockville, Connecticut, dating from 1883, was soon torn off its pedestal and thrown into a nearby lake (in a weird twist of history, a reproduction was commissioned and the statue restored by the town in 2005). Another in Rochester, NY was set upon by men armed with crowbars, who beat the statue off its pedestal and carted it away. Dubuque, Iowa’s statue received similar treatment. Perhaps the most ignominious fate was suffered by a Cogswell statue occurred in his own adopted city, where on the evening of New Year’s Day 1894 a drunken mob of San Franciscans descended upon his likeness and violently tore it to pieces, leaving wreckage, in the words of the San Francisco Examiner, “as unlovely and disrupted as that of Ozymandias.”

Cogswell temperance fountain & statue, destroyed January 1894 (from Moffatt 1992); Headline and drawing from the San Francisco Call, January 3, 1894.

If Cogswell’s statuary remained unloved, he achieved more lasting impact with his educational philanthropy. But there too, his penchant for control made his gifts more difficult to accept. An attempt in 1879 to endow a dental school in his name at the University of California foundered on disagreements with the Board of Regents over how to use his donated property. The Regents balked at Cogswell’s characteristic insistence that the state assume the substantial costs of equipping the school, and the doctor successfully sued to reclaim his property.

More successful was the establishment of the Cogswell Polytechnical College in 1887, funded by a million-dollar property donation. A coeducational institution devoted to imparting a vocational and business education to poor youths, the scale of Cogswell’s generosity in this case assured the ongoing financial viability of the school. However, its first years were very shaky. Here too, Cogswell could not refrain from meddling in the school’s affairs on the grounds that he believed its expenditures were too extravagant, taking its Board of Trustees to court in 1892 in an attempt to wrest back control. The following year, with Cogswell threatening to shut down the school, such moves went over very badly in the public eye. The San Francisco Call decried Cogswell’s school as “an Indian Gift”, while Hearst’s Examiner complained, “cast-iron fountains are the only things that can be safely accepted from him with the assurance that they will not be wanted back again.”

Unable this time to legally wrest back control of his gift, Cogswell reached an accommodation with the Board of Trustees. He remained as its President (as evidenced by his signature on the check above), although apparently only in a titular capacity, busying himself during his last years with tasks like checking on how much chalk was being used in the classrooms.

Henry Cogswell died nearly three years after the check was issued. Characteristically, the biggest of all Cogswell’s monument projects was his own mausoleum, constructed for himself and Caroline (they had no children). The self-designed “Mausoleum to the Worthy Dead”, located in Oakland’s Mountain View Cemetery, embodied the pharaonic potential of Cogswell’s penchant for memorials. Employing some four hundred tons of granite, it features a sixty-foot obelisk flanked at its pedestal by four statues representing Faith, Hope, Charity, and Temperance.

In its obituary for Cogswell, the San Francisco Examiner noted that, despite his career of philanthropy, “it is said that he never spent a dollar unnecessarily.” A few years after his death, the San Francisco Chronicle pointed to Cogswell Polytechnical, and not its namesake’s fountain crusade, as his most meaningful legacy: “That school, and not his monuments and fountains, is what will give his name to posterity, for the school is a monument of which any man might well feel proud.”

Cogswell Polytechnical survived the earthquake of 1906, although another one of Cogswell’s “silent orator” statues, this one located outside the original building in the Mission District, did not. Incarnations of the school persisted under its original name for the next century, though operating in different locales. From its trade school origins, Cogswell Polytechnical developed respectable, niche reputations in such areas as video game design and digital animation. Taken over by a private equity firm in 2010, the school was renamed the University of Silicon Valley in April 2021.

REFERENCES

Corwin, Emile, “Cogswell’s Great Fountain Crusade” Yankee (March 1971), 70-73. 104-113.

Christen, Arden G., Matthew S. Theobald, and Joan A. Christen, “Henry Daniel Cogswell, DDS (1819-1900): A Temperance Advocate, Philanthropist and Builder of Ice-Water Fountains” Journal of the History of Dentistry 47, No. 2 (July 1999), pp. 51-59.

Moffatt, Frederick C. “The Intemperate Patronage of Henry D. Cogswell” Winterthur Portfolio 27, No. 2/3 (Summer-Autumn 1992), pp. 123-142.

San Francisco Chronicle, “The Story of the Unwelcome Cogswell Fountains”, June 19, 1904, p. 10.

San Francisco Examiner, April 12, 1893; May 12, 1893, p. 6; January 4, 1894, p. 4; July 10, 1900 (obituary).

San Francisco Call, May 9, 1893, p. 8; January 3, 1894.

- Loren Gatch's blog

- Log in or register to post comments

More like this

- MAD Magazine and its Troublesome Three-Dollar Bill

- Freedmen, Philanthropy, and Fraud. A History of the Freedman's Savings Bank

- A Green Thread in Fractional Currency

- Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. Announces New Membership Rates and Decision to Continue to Make Old Lifetime Membership Rates Available through Year End at Website Only

- American History as Seen Through Currency