Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

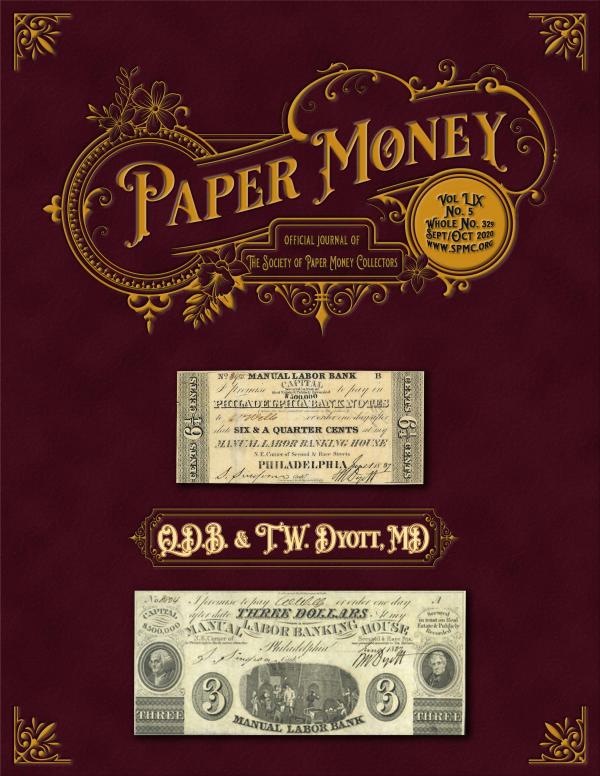

The Curious Career of T. W. Dyott, M.D.—Q. David Bowers

$1 Series of 1923 S.C. Signature Combinations--Peter Huntoon

1917-1924--A Burst of New Type Notes—Peter Huntoon

The Farmers & Merchants National Bank --J. Fred Maples

James J. Ott, Nevada Assay Office—Robert Gill

Commodore Jacob Jones' Gallant Fight Terry Bryan

Coney Island-The Greatest American Park—Steve Feller

official journal of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors

Q.D.B. & T. W. Dyott, MD

1231 E. Dyer Road, Suite 100, Santa Ana, CA 92705 • 949.253.0916

470 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10022 (Fall 2020) • 212.582.2580

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

California • New York • New Hampshire • Oklahoma • Hong Kong • Paris

SBG PM Free Grading 200731 America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

LEGENDARY COLLECTIONS | LEGENDARY RESULTS | A LEGENDARY AUCTION FIRM

Starting immediately, we will pay the grading fees at PCGS, PCGS Banknote, NGC or PMG

for the coins and bank notes you consign to an upcoming Stack’s Bowers Galleries auction. Our

grading giveaway will continue until we have given $1 million in free grading to our clients1.

Upcoming events include auctions of United States coins and currency in November, March

and June, and sales of Ancient and World coins and paper money in January and April. We also

welcome consignments for our popular monthly Collectors Choice Online auctions.

We invite you to contact Stack’s Bowers Galleries today to learn how you can consign to one of our

upcoming auctions and have your coins and paper money graded for free. One of our experts

can discuss your consignment and determine if our free grading program is right for you.

Call Today About Free Grading on Your

Consignment to a Stack’s Bowers Galleries Auction!

800.458.4646 West Coast • 800.566.2580 East Coast

Consign@StacksBowers.com • www.StacksBowers.com

1Terms & restrictions apply

Stack’s Bowers Galleries invites you to take advantage of

FREE Third-Party Grading for items consigned to auction.

FREE GRADING

Stack’s Bowers Galleries Announces

$1 Million Free Grading Program

Q. David Bowers

302

166

366

37

301

360

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

297

Contents continued

Columns

Advertisers

SPMC Hall of Fame

The SPMC Hall of Fame recognizes and honors those individuals who

have made a lasting contribution to the society over the span of many years.

Charles Affleck

Walter Allan

Doug Ball

Joseph Boling

F.C.C. Boyd

Michael Crabb

Martin Delger

William Donlon

Roger Durand

C. John Ferreri

Milt Friedberg

Robert Friedberg

Len Glazer

Nathan Gold

Nathan Goldstein

James Haxby

John Herzog

Gene Hessler

John Hickman

William Higgins

Ruth Hill

Peter Huntoon

Don Kelly

Lyn Knight

Chet Krause

Allen Mincho

Judith Murphy

Chuck O’Donnell

Roy Pennell

Albert Pick

Fred Reed

Matt Rothert

Neil Shafer

Austin Sheheen

Herb & Martha

Schingoethe

Hugh Shull

Glenn Smedley

Raphael Thian

Daniel Valentine

Louis Van Belkum

George Wait

D.C. Wismer

From Your President Shawn Hewitt 299

Editor Sez Benny Bolin 300

Uncoupled Joseph E. Boling & Fred Schwan 352

Quartermaster Michael McNeil 357

Cherry Pickers Corner Robert Calderman 362

Obsolete Corner Robert Gill 364

Chump Change Loren Gatch 366

New Members Frank Clark 367

Small Notes Jamie Yakes 368

Stacks Bowers Galleries IFC FCCB 369

Fred Bart 319 Vern Potter 372

Tom Denly 319 Higgins Museum 372

CSNS 320 DBR Currency 372

ANA 330 Jim Ehrhardt 372

Lyn F. Knight 341 PCDA 385

Gunther & Derby 363 Heritage Auctions OBC

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

298

Officers & Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS

PRESIDENT Shawn Hewitt

shawn@shawnhewitt.com

VICE-PRES. Robert Vandevender II

rvpaperman@aol.com

SECRETARY Robert Calderman

gacoins@earthlink.net

TREASURER Bob Moon

robertmoon@aol.com

BOARD OF GOVERNORS

Mark Anderson mbamba@aol.com

Robert Calderman gacoins@earlthlink.net

Gary J. Dobbins g.dobbins@sbcglobal.net

Stockpicker12@aol.com

Pierre Fricke pierrefricke@buyvintagemoney.com

Loren Gatch lgatch@uco.edu

Steve Jennings sjennings@jisp.net

William Litt Billlitt@aol.com

J. Fred Maples maplesf@comcast.net

Cody Regennitter cody.regennitter@gmail.com

rvpaperman@aol.com

Wendell A. Wolka

purduenut@aol.com

APPOINTEES

PUBLISHER-EDITOR

Benny Bolin smcbb@sbcglobal.net

ADVERTISING MANAGER

Wendell A. Wolka

Jeff Brueggeman jeff@actioncurrency.com

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR

Frank Clark frank_spmc@yahoo.com

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT

Pierre Fricke

WISMER BOOK PROJECT COORDINATOR

Pierre Fricke

From Your President

Shawn HewittFrom Your President

Shawn Hewitt

Paper Money * July/August 2020

6

By the time you read this, you will have been surprised by the

redesign of the cover of our journal, and now you can further explore the

makeover of its contents. Many thanks go to Benny Bolin, Robert

Calderman and Phillip Mangrum for their hard work in re-crafting our

beloved publication. I hope you like it as much as I do.

A few more surprises will be found in this edition, including the

announcement of the 2020 awards that we would have normally made at

our SPMC breakfast at the International Paper Money Show, which was

cancelled because of COVID-19 this year. These awards are for literary

excellence (based on voting from SPMC members), ODP Registry Sets

(also voted upon) and service to the hobby and SPMC. In addition to

these are our 2020 inductees in the SPMC Hall of Fame. They are John

Ferreri, Len Glazer, Allen Mincho and D.C. Wismer.

We are grateful that so many members are passionate about their

hobby and make tangible contributions that benefit the Society and paper

money collectors everywhere. Congratulations to them all.

Congratulations are also in order to William Gunther and Charles

Derby for their new book on Alabama obsoletes. Look for their

advertisement in this issue. I’ve just ordered my copy and can’t wait to

see it. SPMC awarded a well-deserved grant for this effort and the Board

of Governors was pleased to offer its support.

Related to this, our Book Committee, composed of Benny Bolin,

Robert Calderman, Pierre Fricke (chairman), and Wendell Wolka,

recently submitted their SPMC Book Publishing Guidance document for

review by the Board. This was approved and is included in this edition of

the journal. Over the years, the role of SPMC in helping authors of books

related to obsolete notes has evolved considerably. Potential authors

should refer to this document for SPMC’s current guidance on the

subject.

Continue to watch for more improvements in SPMC’s

membership benefits in the coming months. We are still looking forward

to production of educational videos thanks to the efforts of Loren Gatch,

as well as additional content in our Bank Note History Project and

Obsoletes Database Project, and more. Your SPMC leadership is

committed to leaving the place better than they found it. A global

pandemic is not going to get in their way.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

299

Terms and Conditions

The Society of Paper Money Collectors (SPMC) P.O. Box

7055, Gainesville, GA 30504, publishes PAPER MONEY

(USPS 00-3162) every other month beginning in January.

Periodical postage is paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send

address changes to Secretary Robert Calderman, Box 7055,

Gainesville, GA 30504. ©Society of Paper Money Collectors,

Inc. 2020. All rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in

whole or part without written approval is prohibited. Individual

copies of this issue of PAPER MONEY are available from the

secretary for $8 postpaid. Send changes of address, inquiries

concerning non - delivery and requests for additional

copies of this issue to the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere

and publications for review should be sent to the editor.

Accepted manuscripts will be published as soon as

possible, however publication in a specific issue cannot be

guaranteed. Opinions expressed by authors do not

necessarily reflect those of the SPMC. Manuscripts

should be submitted in WORD format via email

(smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending memory stick/disk

to the editor. Scans should be grayscale or color JPEGs at

300 dpi. Color illustrations may be changed to grayscale

at the discretion of the editor. Do not send items of

value. Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release

of the author to the editor for duplication and printing as

needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis. Copy/correspondence

should be sent to editor.

All advertising is pay in advance. Ads are on a “good

faith” basis. Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a premium

contract basis. Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be prepaid

according to the schedule below. In exceptional cases

where special artwork or additional production is

required, the advertiser will be notified and billed

accordingly. Rates are not commissionable; proofs are

not supplied. SPMC does not endorse any company,

dealer or auction house. Advertising Deadline: Subject to

space availability, copy must be received by the editor no

later than the first day of the month preceding the cover

date of the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the March/April issue).

Camera-ready art or electronic ads in pdf format are

required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Space 1 Time 3 Times 6 Times

Full color covers $1500 $2600 $4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half-page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter-page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth-page B&W 45 125 225

Required file submission format is composite PDF

v1.3 (Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted

files should conform to ISO 15930-1: 2001 PDF/X-1a file

format standard. Non- standard, application, or native file

formats are not acceptable. Page size: must conform to

specified publication trim size. Page bleed: must extend

minimum 1/8” beyond trim for page head, foot, and

front. Safety margin: type and other non-bleed content

must clear trim by minimum 1/2” Advertising copy shall

be restricted to paper currency, allied numismatic

material, publications and related accessories. The

SPMC does not guarantee advertisements, but accepts

copy in good faith, reserving the right to reject

objectionable or inappropriate material or edit copy.

The SPMC assumes no financial responsibility

for typographical errors in ads but agrees to reprint that

portion of an ad in which a typographical error occurs.

Editor Sez

Benny Bolin

Hello and welcome to the newly re-designed and

updated Paper Money! We have been talking about this

for a while and with a lot of help and tutelage from Phillip

Mangrum and assistance from Robert Calderman and

Shawn, it is now come to fruition. A few more tweaks and

adjustments may be in the offing but I hope you like the

new pages. The cover redesign is the most obvious and is

really eye-catching. We plan to have a different color each

year for all six issues. We also updated and redesigned the

pages that are essentially the same each issue, albeit with

different text. Those include the president's message, the

editor's message, the Table of Contents (with a second one

added) and the new members page. I also have redone the

title fonts in most of the columns. One thing that has not

changed are the articles themselves. These are what make

the journal the magnificent tome it is. Please shoot me an

email and let me know what you like about the changes

and what other things you think could be changed to make

it even better.

As you can tell from this issue, I am running low

on short to medium length articles. If you have time (if

you need something to do while quarantining, write me a

short one. 2-5 page articles are great and very helpful.

I hope you all are doing well and staying safe

during this incredible pandemic we are having. Being in

the healthcare field as an RN for almost 40 years, it is

amagzing to see what is going on. I personally think the

disease is bad in and of itself, but it is made much worse

by all the super wrong social media and the self-serving

politicians. I have had a much closer exposure to the

whole process than I really wanted as my mom (she was

89 and lived alone independently) fell on Memorial Day

and was down for an extended period of time. I then had

to become her private duty nurse almost full time for the

summer until she passed away in July. I apologize for

anyone who I did not answer emails or other contacts

during that time. And now I am back at school planning

for the return of students to the building. Wow. What fun.

Benny

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

300

The Curious Career of

T.W. Dyott, M.D.

by Q. David Bowers

Introduction

Among my numismatic interests, paper money is in

the front rank. Over a long period of years, I have

studied different banks, their officers, and methods of

distribution. I have also collected various series,

especially obsolete notes. As the years have slipped by,

I have deaccessioned most of the notes, but have kept all

of my research information and have added to it.

In 2006 I completed the manuscript for Obsolete

Paper Money Issued by Banks in the United States 1782

to 1866, which was issued by Whitman Publishing and

had become a best seller and standard reference. In it is

a section devoted to Dr. Thomas W. Dyott and his

Manual Labor Bank. Located in the Kensington district

of Philadelphia, it and its founder have in parallel two of

the most fascinating and almost unbelievable histories.

In the present study I share what I have learned

about this unique enterprise, a narrative full of surprises,

unique in the history of American currency.

The Early Years

Thomas W. Dyott

Thomas W. Dyott was born in England in 1777. As

a young man he sailed to America and arrived in

Philadelphia in 1804 or early 1805. In 1807 the city

directory listed him for the first time as owner of a

“Patent medicine warehouse, No. 57 South Second

Street.” The Philadelphia Gazette, January 24, 1807,

carried this advertisement:

It is obvious that by this time Dyott had his fingers

in many business pies, early evidence of his

entrepreneurship. His narrative, written in a convincing

manner, would be essential in his future enterprises. In

April 1807 he ran large advertisements for Dr.

Robertson’s Celebrated Stomachic Elixir of Health and

Dr. Robertson’s Patented Stomachic Wine Bitters.

These were “Prepared only by T.W. Dyott, sole

proprietor and grandson of the late celebrated Dr.

Robertson, physician in Edinburgh, and sold wholesale

and retail at the proprietor’s medicine warehouse, No.

57, South Second Street.” Sans Pareille Oleaginous

Paste to improve the beauty of the mahogany and other

hardwood furniture was another product, not to

overlook his agency for Bug-Destroying Water. A list of

his items sold for health and beauty would be lengthy.

In 1809 his business was listed as “Medical

dispensary and proprietor of Robertson’s family

medicines, No 116 North Second Street.” By that time

it seems that his brother John had joined him in the trade.

Thomas W. Dyott, M.D. as seen

on a bank note of the 1830s.

Pro Bono Publico

Patent water proof Brunswick Blacking. Prepared with oil, which softens and

preserves the leather—words cannot set forth its just praise, nor can its

transcendent qualities be truly known, but by experience—it is particularly

recommended to sportsmen and gentlemen who are much exposed to the wet, as

it will prevent the water from penetrating, preserve the leather from cracking, and

render it supple and pleasant to the last.

Prepared and sold, wholesale and for exportation, with full directions for

using it, by T.W. Dyott, at his medical warehouse, No. 57 S. Second Street,

Philadelphia, second door from Chestnut Street; also by appointment at J.B.

Dumontet’s, No. 120 Broad Street, Charleston, South Carolina, where may be

had the Imperial Wash for taking out stains, and preserving the quality and colour

of saddles, and the tops of boots, prepared only by T.W. Dyott, who has for sale

an assortment of brushes of superior quality for using the patent blacking.

N.B. Captains of ships and storekeepers throughout the United State will be

supplied on the most reasonable terms, and their orders punctually attended to

and executed at the shortest notice.

T.W.D. has also for ale, patent wine, bitters of a superior quality, together

with a variety of patent family medicines, essences, perfumery, &c. suitable for

the West Indian and other markets.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

301

Dyott continued to make liquid blacking. In 1810 he is

listed for the first time with “M.D.” after his name. It is

not known if he had actual medical training. In that era

there were no licensing requirements, and the patent

medicine field was rife with “doctors.” In that year he

claimed to have 41 agents in 36 towns and cities in 12

states, including 14 in New York State. On September

3, 1811, he moved to 137 Second Street in Philadelphia,

the address where he maintained a store for years

afterward.

In the Philadelphia General Advertiser, July 1,

1815, he advertised to have had “long experience and

extensive practice in the City of London, the West

Indies, and for the last nine years in the City of

Philadelphia.” In 1815 he married Elizabeth, and in

October 1816 the couple had a son, John Dyott. In 1822,

Thomas W. Dyott, Jr. was born. In 1815, John G.

O’Brien became a partner in O’Brien & Dyott, of which

few details are known today. In 1816, in addition to his

main store, he had an outlet at 341 High Street.

Probably as a result of needing glass bottles and

flasks for his products, he became involved in wholesale

distribution of various related items. By 1817 he was the

sole agent for the Olive Glass Works in Glassboro, New

Jersey, the New Jersey Union Glass Works in Port

Elizabeth in the same state, and for the Gloucester Glass

Works in Clementon, also in New Jersey. It is likely he

had an ownership interest in some or all.

Moving forward to 1820, he advertised his Cheap

Drug, Glass, and Family Medicine Warehouse at 137 &

139 North Second Street, corner of Race Street. He

offered dozens of patent medicines, dye stuffs, sundries,

and other products, including many items of glass ware.

An advertisement in the local Democratic Press, March

11 of that year, had this at the bottom: “Wanted: Two

apprentices to the drug business. Boys from the country

will be preferred, they will be required to be of good

moral habits, of respectable connections, have a good

English education and knowledge of the German

Language.”

T.W. Dyott’s store as advertised in 1820.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

302

The Democratic Press, July 17, 1820, carried an

advertisement stating that the Olive, Gloucester, and

Kensington Glass Manufactories, informed readers that

“they have appointed Dr. T.W. Dyott, druggist, their

sole agent, with whom all the glass as it is manufactured

will be deposited for sale, by which means, from the

extensive stock generally on hand, almost every order

can be executed at an hour’s notice.” Signed by “David

Wolf & Co., Olive Glass Works; Jona. Haines,

Gloucester Glass Works; Hewson & Connell,

Kensington Glass Works.” The outlet was at the old

stand at the corner of North Second and Race streets.

The Commercial Directory, 1823, lists these businesses:

Kensington Cylinder Glass Works. T.W. Dyott,

proprietor.

Kensington Hollow Ware Glass Works. T.W. Dyott,

proprietor.

Olive Glass Works, in Gloucester County, New Jersey.

Manufacture bottles and vials. T.W. Dyott, agent.

Dyott, T.W. Druggist & colourman; manufacturer of

window glass, &c., 137 & 139 North Second Street

[Philadelphia]

Dyott’s actual ownership interest in Kensington at

this time has not been determined. Among his products

were whiskey flasks with patriotic themes, including

eagles and General Washington, not to overlook those

with his own image. These are widely collected today.

During this period he borrowed a lot of money to

finance his enterprises, causing concern among his

creditors when repayments became slow. However, he

persevered and my mid-decade it seems that he had

surmounted these difficulties.

In the United States Gazette, Philadelphia, October

19, 1824, he advertised “Washington, LaFayette,

Franklin, Ship Franklin, Agricultural and Masonic,

Cornucopia, American Eagle, and common ribbed

Pocket Flasks.” In the same publication he advertised on

March 14, 1825, that he had 3,000 dozen flasks

available for purchase. After the deaths of John Adams

and Thomas Jefferson, they were commemorated on

flasks as well.

In this era two of his important sources for finance

were Philadelphia merchants Jacob Ridgway and

Captain Daniel May, both of whom were prominent in

the local social scene. Dyott complained of the high

interest they charged, but continued the relationships.

These arrangements were not known to others outside

of Dyott’s inner circle and came to light years later in

1839 court proceedings, as explained later in the present

text.

On May 17, 1826, in the Cayuga Republican issued

in distant Auburn, New York, he advertised his

Philadelphia store, also indicating that he was involved

in glass manufacture: “3 or 4 first rate vial blowers will

meet with constant employment and good wages by

applying as above.” Not long afterward his

advertisements told of his ownership, such as this notice

in the Commercial Advertiser, New York City, June 18,

1828:

Lafayette-Eagle flask by Dyott Franklin-Dyott flask with T.W. Dyott’s portrait on one side

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

303

Dyott secured several patents relating to glass making. The glass factories were expanding by leaps and bounds.

To add to the work force, advertisements were placed, such as this in the Philadelphia Inquirer, July 19, 1832:

Glass factory workers as illustrated on a bank note.

As to the history of the glass factory, it dated back

to 1771 when Robert Towers, a leather-dresser, and

Joseph Leacock, a watchmaker, decided to erect a glass

works in Kensington. They purchased frontage on the

east side of Bank Street (later called Richmond Street),

extending back to the shore of the Delaware River,

which was navigable at that point. The business was up

and running in short order, as evidenced by this notice

in the Pennsylvania Gazette, January 1772: "The glass-

factory, Northern Liberties, next door to the sign of the

Marquis of Granby, in Market Street, where the highest

price is given for broken flint-glass and alkaline salts.”

Not long afterward in November of the same year

the business was sold to druggists John and Samuel

Gray, who added Isaac Gray as a partner. The works

were expanded. In May 1780 the business was sold to

tobacconist Thomas Leiper, who is thought to have

found it to be a convenient source for bottles in which

to store and sell snuff. On March 6, 1800, the factory

was sold to Joseph Roberts, Jr., James Butland, and

James Rowland for $2,333, after which it was known as

James Butland & Co., with an outlet at 80 North Fourth

Street. In 1801 Roberts sold his interest to his partners,

who continued the business until 1804, after which

Rowland became sole proprietor. Rowland in 1808 had

his outlet at 93 North Second Street. In the 1820s, Dyott

was agent, later proprietor.

Glass Ware

Philadelphia and Kensington Factories. Apothecaries’ vials, patent medicine and perfumery do, mustards, cayennes, shop

furniture, confectioner’s show bottles, druggists packing bottles, carboys, acids, castor oil, cordial and wine bottles, demijohns,

flasks, quarts, half gallon, and gallon common bottles, preserving and fruit jars, with a complete and general assortment of

every other article in the glass line.

The above establishment is on the most extensive scale, embracing three distinct factories located in the immediate

vicinity of Philadelphia—affording every facility for executing orders with promptness. The quality of the glass is decidedly

superior to any other of the same description made in this country.

Orders punctually attended to, addressed to the proprietor, T.W. Dyott, Philadelphia, or to H.W. Field, agent, New York.

Apprentices Wanted

A number of boys of industrious habits from the ages of ten to fifteen are wanted as apprentices to the art and science of

glass blowing; in connection with which they will also be taught an additional and distinct trade, leaving them a choice of

following either occupation when they become of age.

The terms on which they will be taken will insure them good boarding, clothing, washing, and lodging, with a privilege

of doing overwork, for which they will be payed journeymen’s wages.

In the arrangement and formation of his establishment the proprietor has spared no expense in making it an advantageous

situation for the boys and meriting the approbation of their parents and friends. Strict attention will be given to their morals

and education, a qualified school-master having been engaged for their sold instruction.

The school house, house of public worship, and dwelling house are all erected on the premises at the factories, which are

situation on one of the most pleasant and healthy locations on the banks of the Delaware near Philadelphia.

The school is open every evening in the week and before and after the hours of worship on Sundays. A regular course of

instruction will thus be maintained during their whole apprenticeship, and those who are anxious to acquire improvement will

meet with every facility.

Apply to T.W. Dyott, corner of Second and Race Streets, or to M. Dyott at the factories in Kensington.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

304

Happy Times at Dyottville

Dyottville

In March 1833 it was announced that the four factories would

henceforth be known as the Dyottville Glass Factories. While

Dyottville was not a name recognized by the state, the designation

was widely known. The growth of the enterprise had many

detractors, including in particular Jeremiah Kooch, publisher of

Kooch’s Blue Book for the County of Philadelphia, who claimed that

much public money was spent in improving the area, including for a

bridge, walls, and fences, and that the county commissioners were

frequent guests of the Dyott family and were treated like royalty.

T.W. Dyott, M.D., was a fraud, an impostor, he alleged. Per contra,

many articles in the popular press praised Dyottville and its

proprietor.

The spread included a farm of about 200 acres on which

vegetables, poultry, and 48 cows (per a May 1833 account) were

situated. Dyottville included housing for all of the workers plus

about 40 houses arranged in a row, for the accommodation of

married persons and their families. The boys were accommodated in

rooms for six to eight, with partitions, deep shelves for storing

clothing and personal effects and other amenities. There were

facilities for washing three times a day, before each meal.

In a separate building the boys had their own dining hall, with

fine provisions. On Christmas, turkeys and plum pudding were the

usual fare. Snacks of crackers were furnished before and after the

noon meal. The adults had their own dining hall.

In May 1833 a reporter from the United States Gazette visited

Dyottville and turned in lengthy glowing report describing

cheerfulness and harmony. Selected excerpts:

…The general government of the place is in persuasion, not coaxing,

persuasion that cheerful obedience to reasonable rules is the best policy.…

On entering one factory, in the center of which was a furnace, having in it ten or twelve melting pots, and employed about

thirty persons, we were struck with the cheerfulness with which all performed the offices assigned to them. On the side of the

furnace opposite to that, on which we and other visitors stood, some one of the workmen commenced singing. He had scarcely

proceeded a note before the whole band of youth and children joined in perfect harmony and time, and carried through in the

most admirable style we have ever heard. It was one of the richest extemporaneous musical treats we have ever enjoyed. It was

carried on without a relaxation of labor on the part of a single individual. The vaulted roof was favorable to the prolongation of

the sound.…

This was no trial “got up” to please the company. Twenty times and perhaps fifty times a day, labor is lightened by the

accompaniment of music in all the factories.

Dyottville was for a long time exclusively conducted by Dr. T.W. Dyott of this city. He has recently associated with his

brother, who with his family occupy the central building of this little ton—where, we are bound to day, true hospitality, its

comforts and graces are fully exercised.…

The Daily Pennsylvanian, Philadelphia, September 9, 1834, included this advertisement:

T.W. Dyott’s store as advertised in 1833

in DeSilver’s Philadelphia Directory and Stranger’s

Guide

A Teacher Wanted,

In an extensive establishment, wherein a School System of Moral and Mental Labor is adopted, for the instruction

of a large number of boys. A person from one of the Eastern states would be preferred He must be a single man, of

pleasing address, industrious habits, and strictly moral character; one who will feel it incumbent on him to impart to the

working boy an elevation of character; and a sentiment of self-dignity that will tend to equalize him with all men, and

that will tach him to brook no distinction of superiority, excepting such as is conferred by virtuous principles.

His entire time will have to be devoted to the interests of his pupils among whom he must associate during their

hours of labor, of study, and of amusement.

To a person thus qualified, a liberal salary will be given. Satisfactory references as to character and capacity will

be required. Apply to

T.W. Dyott Philadelphia

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

305

Dyott’s glass factories in Dyottville on the bank of the Delaware River in the 1830s.

In 1834 The Mechanic, Journal of the Useful Arts and Sciences published this:

In 1833 more than 300 people were employed at the

Dyottville Glass Works, of whom more than 200 were

young apprentices. Most workers lived near the factory,

which was connected to about 400 acres of land along

the river. A farm produced dairy products and

vegetables. In that year he published a brochure, An

Exposition of the System of Moral and Mental Labor

Established at the Glass Factory of Dyottville, in the

County of Philadelphia, mainly to back his unsuccessful

petition to obtain a state charter for a proposed bank.

The author of the publication is not known, but his

talented friend Stephen Simpson may have been

involved. Simpson had been a bank clerk earlier and in

1830s had become a candidate for Congress on the

Workingmen’s Party ticket. In 1831 his treatise,

Working Man’s Manual: A New Theory of Political

Economy on the Principle of Production the Source of

Wealth, was published in Philadelphia. In the next year

his Biography of Stephen Girard was published.

The presentation of Dyott’s philosophy included

this (excerpts):

It is too much the propensity of our nature, to run after

fortune with intoxicating ardour, without considering how

many human hearts we may crush in the heat of the pursuit;

or without paying very punctilious regard to the means by

which we accomplish profit. The passion for gain is often too

powerful to be modulated by Reason, arrested by judgement,

or qualified by justice. It is perhaps to this point that we are

to refer the hitherto neglected point of combining mental and

moral with manual labor.…

I projected the plan of instructing boys in the art of glass

blowing, taking them at so tender an age that their pliant

natures could be molded into habits of temperance, industry,

docility, piety, and perfect moral decorum, under a system of

instruction within the walls of the Factory, fully adequate to

develop all these moral and intellectual faculties, which make

Glass Works

Just above Kensington, near Philadelphia, are the Dyottville Glass Works—one of the greatest curiosities of this

country.

There are four large factories or furnaces each having ten melting pots and constantly employing more than 300 men

and boys. They make 10,000 pounds of glass a day. If they work 310 days in a year they must make 31,000,000 pounds of

glass in a whole year. How many half-pint tumblers would all this glass make, each weighing four ounces.

In making this glass they consume in a year 240,000 lbs. of red lead, 370,000 lbs. pot and pearl ashes, 1,360,000 lbs.

of sand, 2,300 bushels of lime, and 1,550 of salt. (What then is glass made of?)

Part of the fuel which they burn is rosin—at the rate of 50 barrels a day, or more than 15,000 a year. Besides this, they

burn 1,800 cords of pine and oak wood and 1,200 bushels of Virginia coal. Surely this is a most splendid establishment.

Of the 300 laborers, 225 are boys, some of whom are not more than eight years of age. They are taught each evening

the branches of a plain, practical education. They have also a library. Almost all learn to sing, and you may hear the various

companies of laborers singing most delightfully, while busy at their work, sometimes twenty or thirty times a day.

Not a drop of spirit or any other intoxicating liquor is allowed in the whole establishment.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

306

the happy man, the good citizen, and the valuable

operative.…

The mere act of blowing does not cause an exertion of the

lungs and habit soon renders the heat imperceptible.… The

exertion of blowing glass, by giving a slight and healthy

expansion to the chest and lungs, adds vigor and energy to the

whole frame.…

Dyott was a remarkably beneficent employer and

wanted his workmen and apprentices to enjoy their life

experience, highly unusual for the era. He built a chapel

and hired a clergyman to give sermons three times on

Sunday. He held prayer meetings and educational

lectures. Singing lessons were given. A well-stocked

library contained classical volumes.

In 1835 Dyott partnered with Stephen Simpson to

launch on January 4, 1835, The Democratic Herald and

Champion of the People. In a discussion, Simpson had

asked Dyott if he was a Whig or if he was a Democrat.

He replied that he had no particular persuasion, but

voted for the candidate, not the party. Simpson made the

decision, based on the current strength of the

Democratic Party under President Andrew Jackson and

his perception that there were more Democrats than

Whigs among potential readers. Curiously, the name on

the masthead was John B. Dyott, his son who would not

be 21 years of age until the next October.

In practice, the newspaper was light on political

news but mainly consisted of promotional material for

Dyottville and its various glass products. Another sheet,

the General Advertiser and Manual Labor Expositor,

seems to have had a local or regional distribution and

was short-lived. The Democratic Herald lasted for

nearly three years.

Starting in 1836, this advertisement was run in regional papers, as here from the June 4, 1836 issue of the Public

Ledger, Philadelphia.

The Manual Labor Bank

Expanding his business horizons and also to provide a place for workers’ savings accounts, in early 1836, with

Simpson as the business manager and cashier, he formed the Manual Labor Bank. On March 26 this was published,

dated February 1:

Unlike most of its contemporaries, the bank did not

have a state charter despite applying for such. However,

this lack did not seem to bother the authorities, as Dr.

Dyott and his Dyottville had a sterling reputation as

viewed by most of the public. Behind the scenes, Dyott

was often short of funds, having to borrow privately at

high interest rates, as later information would reveal. An

entrepreneur he was, but a money manager he was not.

The engraving firm of Underwood, Bald, Spencer &

Hufty was given the contract to print bank notes of

several different denominations, illustrated with a scene

of the interior of a glass factory with workers engaged

in bottle making. The portrait of Franklin was on one

side of each bill and that of Dr. Dyott on the other,

perhaps representing Dyott’s opinion of Philadelphia’s

most prominent citizens past and present.

Apprentices

A few more boys of health, industrious habits from the age of ten to fourteen years will be taken in as apprentices to the

glass blowing and wicker working in the Dyottville factory system as set forth by the proprietor of that establishment in his

Exposition of Moral and Mental Labor, copies of which are published in pamphlet form and will be presented to those who

feel interested, but applying at the N.E. corner of Second and Race streets.

T.W. Dyott

Six Percent Savings

at the Manual Labor Bank, N.E. corner of Second and Race streets—Capital $500,000; secured in trust on real estate and

publicly recorded.

Deposits for four months, not less than ten dollars, will be received every day on which six per cent per annum will be

allowed, free of all charges of commission. Ten days’ notice will be required of intention to withdraw the deposit at the end

of that period. If no notice to withdraw has been given, the deposit will be held, and the interest for that period carried to the

credit of the depositor, when interest will be allowed on the whole sum to his credit; and the same will be done at the expiration

of every four months, until the notice be given to withdraw the deposit.

T.W. Dyott, President

Stephen Simpson, Cashier

Philadelphia, Feb. 2, 1836

N.B. Savings and deposits will be received after the usual banking hours, until nine o’clock P.M. at the counting house

and deposit office, No. 141 North Second St. two doors above the banking house.

Permanent deposits for one year will be received and the interest paid quarterly at six percent subject to the usual notice

of withdrawal.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

307

This bank-note partnership was new on the

Philadelphia scene and had just recently opened its

doors in the Exchange Building. As the successor to

Murray, Draper, Fairman & Co. and Underwood, Bald

& Spencer, the principals were already well-known.

They included Thomas Underwood, Robert Bald, Asa

Spencer, Samuel Hufty, and Samuel Stiles. In New York

City an office was maintained at 14 Wall Street under

the directorship of Nathaniel and S.S. Jocelyn, well-

known engravers who hailed from Connecticut. The

firm lasted until 1843 when it was succeeded by the

related partnerships of Bald, Spencer, Hufty &

Danforth, Philadelphia, and Danforth, Bald, Spencer &

Hufty, New York City.

On its currency the bank claimed to have

$500,000 in capital “secured in trust on real estate and

publicly recorded,” a phrase continued to be used in

advertising. This large advertisement was published in

late spring 1837, as in the Daily Pennsylvanian,

Philadelphia, on June 2:

Money rolled in from depositors, and the funds

found ready use in financing Dyott’s other enterprises.

Even President Andrew Jackson seems to have endorsed

the bank, per this comment in an advertisement in the

Philadelphia Public Ledger, January 1, 1837:

General Jackson says he can see no objection to

your plan of business, with reference to your banking,

as it is founded on a real security and must depend upon

commercial credit for circulation which is all fair; but

he is decidedly opposed to chartered monopolies, which

sanction a paper credit, without a proper metallic basis.

Dyott and Simpson spent a lot of time hand-signing

as president and cashier the bank’s bills, probably many

thousands of sheets of them. They were the currency of

choice in Dyottville and were readily accepted at par

elsewhere in the Philadelphia district.

Backing for the currency as stated on the bank’s bills.

The Highest Rate of Interest

Six Per Cent per Ann Paid Quarterly, or compound interest carried to the credit of the depositor every three months

and the MANUAL LABOR BANK and Six Per Cent Saving Fund, North-East corner of Second and Race Sts.

Instituted February 2d, 1836.

Capital $500,000

Secured in trust by judgment confessed on real estate and publicly recorded—according to the following

Certificate

Go the 11th day of May, 1836, a bond and judgment, commencing from 2nd February last, was filed in the District

Court for Five Hundred Thousand Dollars, as security for all the responsibilities of banking and saving fund deposits

secured by Dr. Thomas W. Dyott of the City of Philadelphia.

Copy from the endorsement on the bond:

“Entered in the Office of the District Court for the city and county of Philadelphia, and warrant of attorney filed May

11, 1836,”

Pro Prothonotary,

(signed) K Coats

Jacob Ridgway, Esq.

Trustee and bond holder

The Manual Labor Bank and Saving Fund has been established by the proprietor in order to afford a safe depository

for the savings of labor and the surplus of incomes, under an ample security of his estate, at the full rate of legal interest—

a security which he believes no other institution possesses—and a rate of interest which he is certain is not paid by any

other.

His motive for this is to give to the meritorious working man the full legal interest which he ought always to obtain

for his savings; and the individual responsibility of the proprietor affords a guarantee that he will accept no more deposits

than his interest calls for, on the single principle of his liability; and which so effectually guards and protects the common

safety of all the depositors by restricting the amount to be received, to the security pledges of 500,000 Dollars.

Deposits received every day until nine o’clock P.M.

Pamphlets containing the terms and exposition of this establishment to be had gratis at the Banking House.

T.W. Dyott, Banker

Stephen Simpson, Cashier

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

308

Advertisements in the autumn of 1837 were placed by T.W.’s brother, M.B. Dyott:

Sheet of four $1 notes of the Manual Labor

Bank. The individual notes are lettered A to D.

M.B. Dyott’s

Wholesale & retail grocery, provision, and variety stores at the

Dyottville Glass Factories, in the District of Kensington,

Philadelphia County.

N.B. The highest prices (in cash or store goods) will always be

given for all kinds of domestic goods and country produce,

including live and dead stock, by applying as above.

Manual Labor Bank notes taken at par.

Manual Labor Bank 5-cent note.

Manual Labor Bank 6¼ cent note.

Manual Labor Bank 10-cent note. Manual Labor Bank 12½ cent note, June 1, 1837.

Manual Labor Bank 50- cent note.Manual Labor Bank 25-cent note.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

309

On June 30, 1837, the Saturday Evening Post printed this:

According to an early account, these small bills were readily accepted by local merchants and tradesmen in return

for goods and services, but were not accepted at the city banks. According to the Pennsylvania Auditor General’s

report for 1837, this bank had in circulation in denominations of 5, 6¼, 10, 12½, 25 and 50 cents, and 1, 2, and 3

dollars, to the amount of $117,500.

Counterfeit & Loss Prevented:

SMALL BANK BILLS

The proprietor of the Manual Labor Saving Fund (at the request of, and to accommodate the public) having caused

to be inimitably engraved, in first rate style, a series of plates, notes from $3 to 5 cts. printed on bank-note paper, is

now prepared to supply a limited amount of same for public convenience.

These bills effectually baffle all attempts to counterfeit them, and being issued on an ample Security of Real Estate

and redeemed when presented in sums of $5 in the bank bills of this city, no loss can possibly accrue on them. Any

amount of the same, not under 50 cents, will always be received on deposit, to the credit of the holder, at 6 percent

interest, at the Saving Fund. N.E. corner Second and Race Streets

T. W. Dyott.

Stephen Simpson, cashier

Manual Labor Bank, June 22, 1837

Manual Labor Notes in

denominations of $1, $2 and $3

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

310

Manual Labor Bank $5 note,

August 2, 1836. The payee, in this

case Tannahill & Lavender,

represents the first person or entity

to which a newly-signed note was

given.

Manual Labor Bank $10 note,

August 2, 1836.

Manual Labor Bank $100 note,

September 10, 1838, no mention of

interest.

Manual Labor Bank $50 note,

February 2, 1836.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

311

The Financial Panic and Consequences

Financial Difficulties

Dyott did not reckon with the Panic of 1837—nor

did many others. He thought that the unbridled

prosperity of the early 1830s would continue forever.

On May 11, 1837, in Philadelphia 11 banks suspended

the payment of gold and silver coins in exchange for

paper. Soon, all paper became distrusted, but there was

little alternative to using it. Bills sold at a discount in

terms of coins. Large-denomination bills in particular

were viewed with suspicion in the marketplace.

A chill enveloped nearly all businesses in the

country, forcing the closure of thousands and the failure

of many banks. Orders for the glass factories

plummeted, and Dyott saw no prospect for a change

anytime soon. Depositors swarmed the office of the

Mutual Labor Bank from mid-March through May,

during which time the bank’s bills were exchanged for

bills of various state-chartered banks in the region.

There were no longer any silver or gold coins in general

circulation anywhere. During this time, Dyott

maintained that all was well. In the meantime, cash was

given to his family.

No advertisements indicating the Kensington glass

factories were still in operation have been seen after the

summer of 1837. The New York Herald on October 3

included an article about glass factories in America,

including this: “There is one glass house for the

manufacture of bottles in Philadelphia, containing 5

furnaces of 6 pots each, and on the premises there are

280 persons employed.” Likely, this information was

from an earlier source and did not refer to operations in

place in October.

Beginning in July 1837, T.W. Dyott began the

wholesale transfer of his assets and businesses to his

close relatives, taking notes in payment and sometimes

charging rental, as in the case of the glass factory signed

over to brother Michael, who had arrived from England

in the late 1820s. His 16-year-old son was set up as

Thomas W. Dyott, Jr., & Co., retail grocers. The senior

Dyott’s stated purpose for doing this was to permit him

to spend more time with the increasingly busy and

ostensibly prosperous Manual Labor Bank.

Around November 1st a “run” on the Manual Labor

Bank followed a rash of nasty rumors that it was on the

brink of failure. Dyott sprang into action, and

announced a system whereby the bank’s bills would be

redeemed at par at local stores—actually a declaration

of a system that had been working for a long time. On

November 6th Dyott published a reward of $500 to be

paid for the identification of the person who first

circulated the rumor of the bank’s instability.

In August 1838, Dyott announced the issuance of a popular type of currency used by many different banks at the

time:

Post Notes: The notes of the Manual Labor Bank dated one year after the date, either with or without interest of the

denominations of 1, 2, 3, 5 and 10 dollars, are received at their full par value, the same as those notes payable on demand, at the

stores of the subscribers, in payment for groceries, drugs, medicines, paints, glass ware, and every other kind of goods in their

line of trade, at the lowest cash prices, either wholesale or retail.

J. B. & C. W. Dyott, 139 and 141 N. Second Street

T. W. Dyott, Jr. & Co., 143 N. Second Street

M. B. Dyott, Dyottville Glass Factories

NB Notes of larger denominations taken by specie contract

The Messrs. Dyotts invite the attention of druggists, merchants, manufacturers, mechanics, store-keepers, farmers and all

who are favorably disposed to the Manual Labor System and who may be in possession of any of the Manual Labor bank notes

not to part with them below their full par value, but to call at their stores, where every attention will be paid to them.

Fair prices in cash or store goods will be paid for all kinds of country produce and for goods generally of domestic

manufacture.

Some regular (not post) notes were issued with dates slightly later than post notes, as illustrated on the

next page. No record has been found as to specific 1838 notes listed and which are post notes and which

are not, although examination of existing notes shows some that were issued.

On March 26, 1838, and in other issues the Public Ledger, Philadelphia, carried this advertisement:

Post Notes

The notes of the Manual Labor Bank, dated one year after date (either with or without interest), of all denominations, are

received by the subscribers at their full par value, the same as those notes payable on demand, in payment for glass and every

kind of goods in their line of trade, at the very lowest cash prices.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

312

J.B. & C.W. Dyott

Nos. 139, 141, and 143 N. Second St.

M.B. Dyott.

Dyottville, East Kensington.

N.B.—It having been represented by holders of the notes that many persons who advertise to receive the Manual Labor notes

at par are in the habit of imposing an extra price on purchasers, to the amount of from 10 to 25 per cent, when payment is made

in Manual Labor Notes. If persons were to apply to the above stores they can be accommodated with nearly every kind of articles

necessary in a family, and avoid being imposed upon.

By this time Dyott’s debtors operating the businesses he leased and transferred were experiencing

continuing losses as was the bank. However, Dyott endeavored to maintain the appearance of prosperity.

Or, more accurately, nothing has been found in newspaper notices suggesting otherwise. Later

advertisements were mostly brief, such as this from the April 5, 1838, issue of the National Gazette,

Philadelphia:

Druggist’s Bottles, &c.

4,000 packages druggist packing bottles and shop furniture from the Dyottville Factories, for which Manual Labor Bank

notes will be received in payment. For sale by J.B. & C.W. Dyott, Nos. 139, 141, and 143 N. 2nd St.

Manual Labor Bank $10 post note,

May 4, 1838, predating the above-

quoted announcement as do some

other post notes. The interest

provision is crossed out.

Manual Labor Bank $20 post note,

July 21, 1838. The interest

provision is crossed out.

Manual Labor Bank $50 post note,

July 21, 1838. The interest

provision is crossed out.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

313

Beginning on July 22, 1838, this notice was published, in the Philadelphia Public Ledger, July 23:

Post Notes

The notes of the Manual Labor Bank dated one year after date (wither with or without interest), of the denominations of 1,

2, 3, 5, and 10 dollars are received at their full par value, the same as those notes payable on demand, at the stores of the

subscribers, in payment for groceries, drugs, medicines, paints, glass ware and every kind of goods in their line of trade, at the

lowest cash prices, either wholesale or retail.

J.B. & C.W. Dyott,

139 and 141 N. Second St.

T.W. Dyott, Jr. & Co.

No. 143 N. Second Street

M.B. Dyott

Dyottville Glass Factories

N.B.—Notes of larger denominations taken by special contract.

The Messrs. Dyotts invite the attention of druggists, merchants, manufacturers, mechanics, storekeepers, farmers, and all

who are favorably disposed to the Manual Labor System, and who may be in possession of any of the Manual Labor Bank notes,

not to part with them below their full par value, but to call at their stores, where every attention will be paid them.

Fair prices in cash or in store goods will be paid for all kinds of country produce and for goods generally of domestic

manufacture.

Slight variations of the above were published into September. A new venture was announced in the

autumn, such as advertised on October 5, 1838 in the Philadelphia Public Ledger:

Rotary Steam Engines

The subscribers have established a factory at Dyottville in the district of Kensington, where they are building and have

constantly on hand for sale Rotary Steam Engines, of an improved construction under the patent of Ethan Baldwin, the simplicity

and durability of which surpass any other steam engine now in use, and they require one third less fuel.

Engines from five to sixty horse power may be seen in operation and examined every day at the factory.

The subscribers will sell their engines on reasonable terms and guarantee any engine they sell not to cost one dollar for

repairs or packing in two years.

Orders for lathes, slide-rests, cutting wheels, boring cylinders and for machinery in general will be punctually attended to

under the superintendence of George W. Henderson, known as a first rate machinist.

Dyott, Baldwin & Hazelton

These advertisements were published into February 1839.

The Fall of the Dyott Empire

Aftermath

Dr. T.W. Dyott was hardly alone in financial

problems, for at the time thousands of businesses

were failing all across the United States, and the

Hard Times era had begun. His Democratic Herald

and Champion of the People folded literally and

figuratively. Finally, in November 1838, Dyott

filed for bankruptcy in the Insolvency Court. Notice

of his status was published in December.

As various banks failed around the United

States, their presidents, cashiers, and stockholders

usually walked away, without further obligation.

Sometimes legal actions were instituted to recover

funds, especially in instances in which shareholders

simply gave IOUs rather than paying for capital

stock, and owed cash. However, assets were few

and far between, and neither stockholders nor the

public received much for the shares or bills of failed

institutions.

However, with Dyott the situation was

different. He was viewed by many as a captain of

industry, a man of great wealth living in regal

circumstances, but with great concern for working

people, including children. Creditors of his

enterprises denounced him as a fraud and called for

his arrest on criminal charges. On February 5, 1839,

his case was scheduled to be reviewed by a jury at

the court. Upon arrival, Dyott was met with an

angry mob. Hurriedly, he dashed into the nearby

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

314

store of Jacob Ridgway and escaped through the

back door. Accounts of the case were published in

newspapers, overlapping advertisements for steam

engines as given above.

The case was held over, and the judge ordered

him bound over for $10,000 on a charge of

fraudulent insolvency. On March 30 the grand jury

returned a true bill against him. Niles’ National

Register, April 6, 1839, had this account:

Dr. Dyott, the Banker. The Philadelphia papers state that the grand jury of that city have found a true bill containing the

following counts: 1. Colluding and contriving with T.B. and C.W. Dyott, to conceal goods, value $100,000.

2. Fraudulently conveying to T.B. and C.W. Dyott, goods, value $50,000.

3. Colluding and contriving with Th. W. Dyott, Jr., to conceal goods, value $50,000.

4. Fraudulently conveying to T.W. Dyott, Jr., goods, value $2,000.

5. Colluding and contriving with M.B. Dyott, to conceal goods, value $30,000.

6. Colluding and contriving with W. Wells to secrete $480 in money.

7. Fraudulently conveying to Julia Dyott furniture, value $1,000.

8. Concealing goods and merchandise, value $50,000.

9. Concealing $300,000 in money.

10. Concealing $100,000 in money.

11. Concealing $10,000 in money.

All with the expectation to receive future benefit to himself, and with the intent to defraud his creditors.

Then followed a long court trial, April 30 to June 1, on 11 indictments, later reduced to seven. Testimony was

contradictory, ranging from presenting Dyott as a benefactor to mankind who had simply suffered the widespread

effects of the panic, to a malicious criminal who sought to defraud his associates and creditors. On June 1st, the jury

returned a verdict against Dyott, guilty as charged on all counts.

The sentence was to be from one to seven years at hard labor, in

solitary confinement, the length being at the discretion of the judge.

On August 31 the judge delivered a sentence of three years of normal

imprisonment. The case was appealed, Dyott lost again, and went to

the Eastern Penitentiary.

Snippets from the Dyott Court Case

The Highly Interesting and Important Trial of Dr. T.W. Dyott, the

Banker, for Fraudulent Insolvency with the Speeches of Counsel, &c.

By the clerk’s office, Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 1839,

contained 28 pages of court proceedings, prefaced by Dyott’s

testimony and that of his counsel, followed by others. James

Campbell and W.L. Hirst, esquires, acted for the State and Z. Phillips,

J.R. Ingersoll, and C.J. Ingersoll were attorneys for Dyott.

Dyott’s words and those of others shed light on certain dates and

details.

The case of Commonwealth Vs. T.W. Dyott opened in Criminal

Court, District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania,

Wednesday, April 29, 1839, before the Hon. R.T. Conrad, with a jury

of citizens empaneled. Attorney Hirst opened for the prosecution and

presented a list of 11 alleged criminal acts that led to the indictment.

Hirst related that the examination of the situation had started on

February 20 and was completed on March 5. This included interviews

with the defendant.

First of 28 pages of the Dyott trial transcript.

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

315

Dyott had commenced banking on February 2,

1836. “His capital was real estate, pills and plasters,

phials and glasses; he considered himself worth, at that

time $600,000 or $700,000, valued his real estate at

$550,000.” After entering banking he bought the house

next above his bank for $16,000. Dyott claimed he was

not a bookkeeper, and thus few specific records were

available. After the petition was filed, a “Mr. Calder

cold not tell whether the account in his ledger was right

or wrong; balance appears to be overdrawn $233,261.”

Cashier Stephen Simpson had desired that his own

accounts be kept and balanced, but that does not seem

to have been done until July 1837. After that time “the

account was balanced every night, and the daily account

was in the books; his discounted notes were all privately

bought, he kept no bill book.” The last refers to Dyott

selling large quantities of bills at deep discounts and

keeping no record.

On Tuesday, May 2, the court reconvened at the

usual hour of ten in the morning. Mr. Hirst continued his

testimony based upon his earlier investigation. “He said

that he asked Dr. Dyott if he could say how many bills

appeared discounted in the books of the bank. He said

he could not say what books they appeared in, or what

the amount was. He said he kept no memorandum,

private or public, of bills discounted.” Dyott related that

the discounted notes were “shaved” (sharply

discounted) to get loans. Upon questioning if the amount

was half a million dollars, or what, Dyott had no

information. Bills were given to lenders such as

Ridgway and also to Dyott’s family, without records

being kept.

Dyott had related that in the summer of 1837 he had

sold his glassware and other stock to his son and nephew

for $150,000 and had been paid in Manual Labor Bank

bills. The glass factories were leased to his brother M.B.

Dyott for $25,000 per year in rent. Dr. Dyott related that

his brother “had stripped it of everything.” [Nothing was

related how the operation was shut down or what

happened to the employees, the farm, and other people

and activities.] Mention was made of the new steam

engine manufactory at Dyottville that was expected to

add profit, but resulted in a loss. This was under the

aegis of his brother until his passing from “mortification

of the throat” on December 31, 1838, seemingly leaving

little in the way of records. [The steam engines did not

operate properly despite Baldwin being on the premises

constantly; details in the Philadelphia Public Ledger,

March 1, 1839.] As to the amount of bank bills that had

been issued, Dr. Dyott said he did not know, but thought

it was about $140,000, not including post notes, and that

at one time there was $108,000 in an iron chest and some

other notes in the glass store.

Hirst then proposed to discuss three items that Dyott

had printed and distributed: “A Reward of $500,” dated

November 6,1837; “Final Arrangement of Business,”

December 5, 1837; and “Regulations for the Business of

the Manual Labor Bank,” December 5, 1837. Attorney

Phillips then arose for the defense, stating that these had

nothing to do with the evidence and could not be

admitted into testimony.

Hirst then resumed his testimony, that regarding the

first, Dyott had said, “It is my real estate. I got 500 or

1,000 copies of that pamphlet printed. None were

circulated with my knowledge or approbation.”

[Perhaps without was intended in the transcript?]

A bond was assigned to creditor Ridgway and was

publicized, as both men thought it would enhance the

apparent credit of the troubled bank. [Further testimony

seemed strange, such as Dyott selling his house furniture

to sister-in-law Julia Dyott because “I wanted money.”]

“I was my own broker in getting a great many

discounts, but I cannot say the amount within

$100,000,” Dyott was quoted as saying. [This would

seem to indicate that hundreds of thousands of dollars in

bills had been issued; at the time it was standard policy

of various bank note printers to issue any quantities

called for, without any concern or investigation.

Numismatically, this reflects that no realistic estimate

can be made of the number of notes printed or issued.]

Dyott had told Hirst that he had acquired the glass

works 20 years earlier, when it was a “mere swamp.” “It

had cost him originally $42,000 and [he] had since spent

less than $300,000. It had 1,000- or 1,200-feet river

front. The house at the corner of Second and Race streets

cost him $15,000. He erected a warehouse on it which

cost $9,000. Bought the lot adjoining for $8.000, and [in

Dyottville] on 40 houses there was a mortgage of

$16,000, on a cost of $9,000, and on Dyottville [a

mortgage] of $20,000 and on the Second Street property

$29,000.”

Attorney Phillips related that when he began

banking, he was looking for a large capital for the glass

business, but had paid off most of it. “Being asked why

he sold out his stock to his relations, he said that he gave

it to them, a as he had enough to attend to, , besides, he

would increase his banking capital by those means. He

was paying thirty per cent a year for money, and

expected to relieve himself by his bank. In a question

about money, he said, ‘I am the Manual Labor Bank.’

Mr. Simpson is trusted by me entirely, he had the power

to manage everything, but much of the discounting was

done by me, and the bank never saw the notes.”

Later in court on the same day, Attorney Phillips

related that $115,000 in post notes was issued. Dyott

told Philipps that “if he could have got out $500,000 of

his bills, and kept them out, he would have done very

well.” [It seems to the present-day reader and must have

seemed to the jury in 1839 that Dyott’s financial empire

was built on debt with an attempt to correct that by

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

316

fraud. This scenario was quite different from the early

accounts of workers happily working and singing, and

Dyottville being a model business and community.

During these procedures Dr. Dyott was brought from jail

to observe the court.

On Friday, May 3, the court opened at the usual

time, with prosecution Attorney Hirst continuing his

narrative, telling of his Dyott interviews: “I examined

him when he stated that $10,800 of post notes were

made in December 1837, that $7,000 of them were put

in circulation, that there were $775 in 50s and 25s [sic]

issued with S. Simpson’s fac simile, that there was an

issue of $90,000 of post notes of large denominations,

that the greater part were issued—perhaps all, that there

were no fresh signatures of post notes after the

$115,000, and that was the whole amount. There was an

issue of $90,000 of cash notes on the day the bond was

reassigned, of which issue Mr. Ridgway has $40,000

and Captain Man had likewise $32,000.”

In other testimony it was related that the first time

Dyott saw Stephen Simpson was that when he was on

board a steamboat in which Simpson was a fellow

passenger. Dyott was seeking a charter for his bank, and

Simpson said he had the political connections to help,

including with President Jackson [who had nothing to

do with state banking]. It was then or shortly afterward

that Simpson suggested the proposed bank take a

political stance, and the Democratic Party was decided

upon, with working men being the base.

Dyott told him that his property was worth

$700,000, and Simpson said this was a fair figure. Going

forward to 1839, Dyott stated that he had no idea of what

his indebtedness was.

On the first day of the bank’s operation, Dr. Dyott

had brought in $150 in specie “and perhaps there also

might have been from $50 to $100 in bank notes.”

Simpson understood that before the bank opened, Dyott

had issued $3,000 to $5,000 in bank notes that he and

Dyott had signed. Deposits rolled in to about $150,000,

all of which was personally turned over to Dyott, who

issued promissory notes in a like amount. The workmen

at the glass works were owned money, Dyott stated [and

it likely that some of the money went to them, but this

was not stated.]

On Monday, May 6, Dr. Dyott, who had been

indisposed and not able to leave prison, came to the

courtroom at the suggestion of prosecutor Hirst.

Stephen Simpson was then brought to the stand to

testify. His comments were wide-ranging. The earliest

issued of fractional bills went mainly to country

people—farmers and average citizens—and took the

place of coins after banks had suspended specie

payments. A copy of the printed “Exposition of the

Manual Labor Bank” was shown, showcasing American

manufactures, particularly glass. In the first run 5,000 to

10,000 were distributed, followed by other editions up

to the fourth and possibly the fifth.

Simpson said that he did not know anything about

the post notes until he first saw them during the trial

depositions. Dyott countered this by saying that he and

Simpson “had signed notes from 8 o’clock A.M. to 3

P.M., from 4 P.M. to 11 P.M., and from 5 A.M. to 7

A.M.” Dyott had wanted Simpson to “sign as late at 12

and 1 at night.”

Going back to early 1837, there were clandestine

and unauthorized issues of paper money. After July

1837, according to Simpson, when citizens brought bills

of other banks to be deposited, Dyott took them

personally and replaced them with Bank of Manual

Labor notes.

In other testimony, seemingly contradictory, it was

stated that as of July 1838, Simpson had signed about

$100,000 in post notes and had delivered them to Dyott.

On Wednesday, May 8, Simpson was first on the

stand. On this and succeeding days, many details were

given of how bills were circulated, how assets were

moved around, and other matters largely beyond the

purview of the present narrative as they added little to

information about the signing of or quantities issued of

the notes.

There was a movement to implicate Jacob Ridgway,

whose name had appeared in advertisement as “trustee”

of the bank. Testimony revealed that this was part of the

fraud, as Ridgway was owed a lot of money by Dyott

and suggested that as is (Ridgway’s) reputation as a

financier and civic leader was excellent, this would draw

more deposits. Ridgway emerged unscathed by the court

case.

Another Account of the Case

The November 1839 issue of The Merchant’s Magazine and Commercial Review included a lengthy

account, here excerpted.

Fraudulent Bankruptcy

The recent trial of Thomas W. Dyott, in Philadelphia, has caused so much excitement there, and is fraught with so much that

is instructive in a mercantile point of view, that we are induced to give an extended account of the case. A few years since, Dr.

Dyott established the famous Manual Labor Bank in Philadelphia, and by means of circulars, advertisements, and false

representations, induced a great many people, principally of the middling interest and poorer classes, to deposit their earnings in

his bank. The institution became insolvent, and the banker applied for a discharge as an insolvent. After a long examination, the

court refused to grant the application, and committed him to jail in accordance with the following provision of the law.…

Paper Money * Sept/Oct 2020 * Whole No. 329

317

There was also much documentary evidence. The jury returned a verdict of guilty. At a subsequent day, the defendant moved

for a new trial; but after a full and elaborate argument, the court overruled the motion, and he was sentenced to confinement in

the Eastern Penitentiary three years. Dr. Dyott is more than seventy years of age.…

“It is impossible,” says the Philadelphia Gazette, “to contemplate the imprisonment of this man, at the age of seventy years,

with his gray hairs, in solitary confinement and at hard labor, without feelings of commiseration for himself, his family, and his

friends.” “We believe,” adds that paper, “Dr. Dyott guilty of fraudulent insolvency. The trial, after a long and most patient

investigation, has so decided.” And “one cannot contemplate the losses of special depositors in the Dyott bank, without

indignation and sorrow; yet pity mingles with a feeling of justice, when the main actor in the fraud, bent with years, goes into

the gloomy recesses of a penitential cell, there, perhaps, to end his days.”…

These were the principal facts in the case, on which the counsel for the government o that there was probable cause for

binding the defendant over to answer the following charges, viz.: 1. Conspiracy to establish an unlawful bank. 2. Conspiracy to

support an unlawful bank with a false capital. 3. Conspiracy to support an unlawful bank with a false capital, knowing the

representation of capital to be false. And each of these with a view to cheat and defraud the citizens of the Commonwealth.…

Beware of Over-Trading: If by depending upon fictitious credit, you extend your business very far beyond your real capital,

the hazard of bankruptcy and ruin will be great. In this case, you risk not only your own property, but that of your creditors,

which is hardly reconcilable with honest principles. When the profits of trade happen to be greater than ordinary, over-trading

becomes general; and, if any sudden change occurs in the state of the commerce or currency of the country, a revulsion must

inevitably ensue, and consign thousands to unexpected ruin.

After serving about a year and a half in prison, T.W.

Dyott was pardoned by Governor David Rittenhouse

Porter and became a free man.

Soon, his creditors caused his re-arrest as a debtor,

and he was sent to the Debtor’s Apartment at the

Moyamensing Prison, where he stayed for just a week

or two after Daniel Man stood as surety for his future

appearances in the Insolvent Court. His assets were

liquidated by sheriff’s sale and auction in 1841. It was

estimated that approximately $250,000 due to

depositors and bill holders of the Manual Labor Bank

might yield about 10 cents on the dollar.

In time, although Dyott never became prominent in

business, he fit back into the community. Products

bearing his name were advertised well into the 1840s,

these including Dyott’s Toothache Drops, Vegetable

Purgative Compound, and Circassian Eye Water, among

others.

Dyott lived among his society and friends until he

died of old age in Philadelphia on January 17, 1861. His

death certificate listed his occupation as druggist. He

was buried in the Union Church graveyard.

The Glass Factories: Epilogue