Please sign up as a member or login to view and search this journal.

Table of Contents

Printing Sequence & a Variant of the 50c Alabama Notes--Charles Derby

Mono-Color Overprinting Created Distinctive Errors--Peter Huntoon, et. al

Unpopular First Issue Bank of Israel Notes--Carlson Chambliss

The Katahdin Iron Works and its Scrip--David Schenkman

Salvaged $10 Silver Certificate Faces 86 & 87--Jamie Yakes

Some Additional Comments re: Mexican 10,000 Peso Note--Carlson Chambliss

E. S. Wells was "Rough on Rats"--Loren Gatch

Legal Tender Series of 1928D $10 FRNs--Jamie Yakes

Mythology & South Carolina Colonial Notes--Benny Bolin

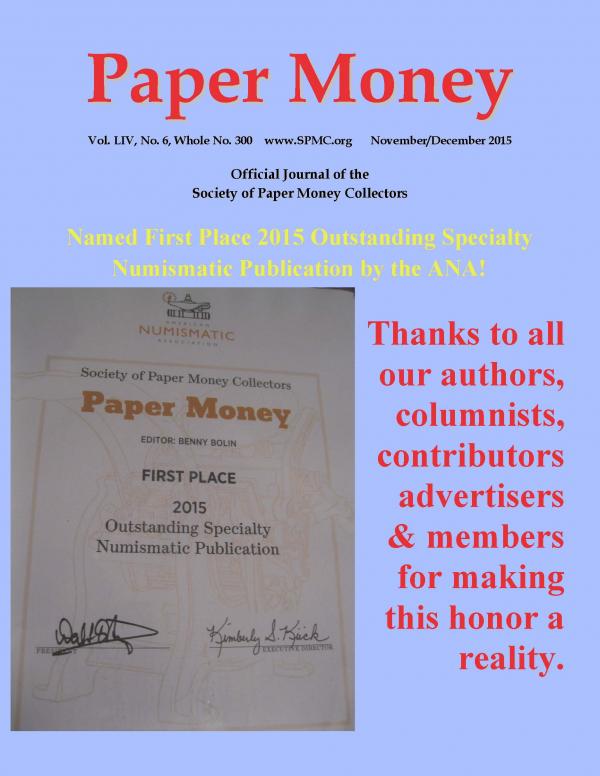

Paper Money

Vol. LIV, No. 6, Whole No. 300 www.SPMC.org November/December 2015

Official Journal of the

Society of Paper Money Collectors

Named First Place 2015 Outstanding Specialty

Numismatic Publication by the ANA!

Thanks to all

our authors,

columnists,

contributors

advertisers

& members

for making

this honor a

reality.

800.458.4646 West Coast Offi ce • 800.566.2580 East Coast Offi ce

1063 McGaw Avenue Ste 100, Irvine, CA 92614 • 949.253.0916

Info@StacksBowers.com • StacksBowers.com

New York • Hong Kong • Irvine • Paris • Wolfeboro

SBG PM ConsNovBalt2015 150811 America’s Oldest and Most Accomplished Rare Coin Auctioneer

Stack’s Bowers Galleries takes tremendous pride in the expertise and competency

of our associates, which include some of the most prominent numismatic

authorities in the world.

Whether you are a seasoned collector or are looking forward to your rst consign-

ment, the experts at Stack’s Bowers are just a phone call away, ready to share our

numismatic knowledge and guidance to help you earn top dollar for your currency.

Stack’s Bowers Galleries is accepting consignments to auctions throughout the year,

including the O

cial Auctions of the Whitman Baltimore Expos.

Peter A. Treglia

PTreglia@StacksBowers.com

John M. Pack

JPack@StacksBowers.com

Brad Ciociola

BCiociola@StacksBowers.com

Professionals You Can Trust

When you are ready to consign, it is imperative that the professionals you

choose to work with are as knowledgeable about your currency as you are.

e Stack’s Bowers Galleries O

cial Auction

of the Whitman Coin and Collectibles Baltimore Expo

November 5-8, 2015 • Baltimore, Maryland

Consign U.S. Lots by September 16, 2015

Call one of our currency consignment specialists to discuss opportunities

for upcoming auctions.

ey will be happy to assist you every step of the way.

800.458.4646 West Coast Offi ce • 800.566.2580 East Coast Offi ce

Peter A. Treglia LM #1195608

John M. Pack LM # 5736

Brad Ciociola

Peter A. Treglia

John M. Pack

Brad Ciociola

Showcase Auctions

Terms and Conditions

PAPER MONEY (USPS 00-3162) is published every

other month beginning in January by the Society of

Paper Money Collectors (SPMC), 711 Signal Mt. Rd

#197, Chattanooga, TN 37405. Periodical postage is

paid at Hanover, PA. Postmaster send address

changes to Secretary Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal

Mtn. Rd, #197, Chattanooga, TN 37405.

©Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc. 2014. All

rights reserved. Reproduction of any article in whole

or part without written approval is prohibited.

Individual copies of this issue of PAPER MONEY are

available from the secretary for $8 postpaid. Send

changes of address, inquiries concerning non-

delivery and requests for additional copies of this

issue to the secretary.

MANUSCRIPTS

Manuscripts not under consideration elsewhere and

publications for review should be sent to the Editor.

Accepted manuscripts will be published as soon as

possible, however publication in a specific issue

cannot be guaranteed. Include an SASE if

acknowledgement is desired. Opinions expressed by

authors do not necessarily reflect those of the SPMC.

Manuscripts should be submitted in WORD format

via email (smcbb@sbcglobal.net) or by sending

memory stick/disk to the editor. Scans should be

grayscale or color JPEGs at 300 dpi. Color

illustrations may be changed to grayscale at the

discretion of the editor. Do not send items of value.

Manuscripts are submitted with copyright release of

the author to the Editor for duplication and printing as

needed.

ADVERTISING

All advertising on space available basis.

Copy/correspondence should be sent to editor.

All advertising is payable in advance.

All ads are accepted on a “good faith” basis.

Terms are “Until Forbid.”

Ads are Run of Press (ROP) unless accepted on a

premium contract basis.

Limited premium space/rates available.

To keep rates to a minimum, all advertising must be

prepaid according to the schedule below. In

exceptional cases where special artwork, or

additional production is required, the advertiser will

be notified and billed accordingly. Rates are not

commissionable; proofs are not supplied. SPMC

does not endorse any company, dealer or auction

house.

Advertising Deadline: Subject to space availability,

copy must b e received by the editor no later than

the first day of the month preceding the cover date of

the issue (i.e. Feb. 1 for the March/April issue).

Camera ready art or electronic ads in pdf format are

required.

ADVERTISING RATES

Space 1 Time 3 Times 6 Times

Full color covers $1500 $2600 $4900

B&W covers 500 1400 2500

Full page color 500 1500 3000

Full page B&W 360 1000 1800

Half page B&W 180 500 900

Quarter page B&W 90 250 450

Eighth page B&W 45 125 225

Required file submission format is composite PDF

v1.3 (Acrobat 4.0 compatible). If possible, submitted

files should conform to ISO 15930-1: 2001 PDF/X-1a

file format standard. Non-standard, application, or

native file formats are not acceptable. Page size:

must conform to specified publication trim size. Page

bleed: must extend minimum 1/8” beyond trim for

page head, foot, front. Safety margin: type and other

non-bleed content must clear trim by minimum 1/2”

Advertising copy shall be restricted to paper

currency, allied numismatic material, publications and

related accessories. The SPMC does not guarantee

advertisements, but accepts copy in good faith,

reserving the right to reject objectionable or

inappropriate material or edit copy.

The SPMC assumes no financial responsibility for

typographical errors in ads, but agrees to reprint that

portion of an ad in which a typographical error occurs

upon prompt notification.

PAPER MONEY

Official Bimonthly Publication of

The Society of Paper Money Collectors, Inc.

Vol.. LIV, No. 6 Whole No. 300 Nov/Dec 2015

ISSN 0031-1162

Benny Bolin, Editor

Editor Email—smcbb@sbcglobal.net

Visit the SPMC website—www.SPMC.org

Printing Sequence & a Variant of the 50c Albama Note

Charles Derby ............................................................... 384

Mono-Colore Overprinting Created Distinctive Errors

Peter Huntoon, et.al ...................................................... 394

Unpopular First Issue Bank of Israel Notes

Carlson Chambliss ....................................................... 403

The Katahdin Iron Works and Its Scrip

David Schenkman ......................................................... 410

Uncoupled—Joe Boling & Fred Schwan .............................. 416

Salvaged $10 Silver Certificate Faces 86 & 87

Jamie Yakes ................................................................. 426

Some Additional Comments re: Mexican 10,000 Peso Note

Carlson Chambliss ....................................................... 431

E. S. Wells was “Rough on Rats”

Loren Gatch .................................................................. 434

Chump Change—Loren Gatch ............................................. 439

Small Notes—“Legal Tender Series of 1928D $10 FRNs

Jamie Yakes ................................................................. 440

Obsolete Corner—Robert Gill .............................................. 442

Mythology & South Carolina Colonial Notes

Benny Bolin .................................................................. 444

President’s Message ............................................................. 446

Editor’s Message ................................................................... 447

New Members ....................................................................... 448

NumisStorica.com ................................................................. 449

Money Mart ............................................................................ 452

Society of Paper Money Collectors

Officers and Appointees

ELECTED OFFICERS:

PRESIDENT--Pierre Fricke, Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776

VICE-PRESIDENT--Shawn Hewitt, P.O. Box 580731,

Minneapolis, MN 55458-0731

SECRETARY—Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mtn., Rd. #197,

Chattanooga, TN 37405

TREASURER --Bob Moon, 104 Chipping Court,

Greenwood, SC 29649

BOARD OF GOVERNORS:

Mark Anderson, 115 Congress St., Brooklyn, NY 11201

Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mtn. Rd #197, Chattanooga, TN

Gary J. Dobbins, 10308 Vistadale Dr., Dallas, TX 75238 Pierre

Fricke, Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776

Loren Gatch 2701 Walnut St., Norman, OK 73072

Shawn Hewitt, P.O. Box 580731, Minneapolis, MN 55458-0731

Kathy Lawrence, 5815 Clendenin Ave., Dallas, TX 75228

Scott Lindquist, Box 2175, Minot, ND 58702

Michael B. Scacci, 216-10th Ave., Fort Dodge, IA 50501-2425

Robert Vandevender, P.O. Box 1505, Jupiter, FL 33468-1505

Wendell A. Wolka, P.O. Box 1211, Greenwood, IN 46142

Vacant

Vacant

APPOINTEES:

PUBLISHER-EDITOR-----Benny Bolin, 5510 Bolin Rd.

Allen, TX 75002

EDITOR EMERITUS--Fred Reed, III

ADVERTISING MANAGER--Wendell A. Wolka, Box 1211

Greenwood, IN 46142

LEGAL COUNSEL--Robert J. Galiette, 3 Teal Ln.,

Essex, CT 06426

LIBRARIAN--Jeff Brueggeman, 711 Signal Mountain Rd. # 197,

Chattanooga, TN 37405

MEMBERSHIP DIRECTOR--Frank Clark, P.O. Box 117060,

Carrollton, TX, 75011-7060

IMMEDIATE PAST PRESIDENT- - M ark Anderson,

115 Congress St., Brooklyn, NY 11201

WISMER BOOK PROJECT COORDINATOR--Pierre Fricke,

Box 1094, Sudbury, MA 01776

REGIONAL MEETING COORDINATOR--Judith Murphy,

Box 24056, Winston-Salem, NC 27114

BUYING AND SELLING

CSA and Obsolete Notes

CSA Bonds, Stocks &

Financial Items

Auction Representation

60-Page Catalog for $5.00

Refundable with Order

ANA-LM

SCNA

PCDA CHARTER MBR

HUGH SHULL

P.O. Box 2522, Lexington, SC 29071

PH: (803) 996-3660 FAX: (803) 996-4885

SPMC LM 6

BRNA

FUN

The Society of Paper Money Collectors was organized in 1961 and

incorporated in 1964 as a non-profit organization under

the laws of the District of Columbia. It is affiliated

with the ANA. The Annual Meeting of the SPMC is

held in June at the

International Paper Money Show in

Memphis, TN. Information about the

SPMC, including the by-laws and

activities can be found at our website, www.spmc.org. .The SPMC

does not does not endorse any dealer, company or auction house.

MEMBERSHIP—REGULAR and LIFE. Applicants must be at

least 18 years of age and of good moral character. Members of the

ANA or other recognized numismatic societies are eligible for

membership. Other applicants should be sponsored by an SPMC

member or provide suitable references.

MEMBERSHIP—JUNIOR. Applicants for Junior membership must

be from 12 to 17 years of age and of good moral character. Their

application must be signed by a parent or guardian.

Junior membership numbers will be preceded by the letter “j” which

will be removed upon notification to the secretary that the member

has reached 18 years of age. Junior members are not eligible to hold

office or vote.

DUES—Annual dues are $39. Dues for members in Canada and

Mexico are $45. Dues for members in all other countries are $60.

Life membership—payable in installments within one year is $800

for U.S.; $900 for Canada and Mexico and $1000 for all other

countries. The Society no longer issues annual membership cards,

but paid up members may request one from the membership director

with an SASE.

Memberships for all members who joined the S o c i e t y

prior to January 2010 are on a calendar year basis with renewals

due each December. Memberships for those who joined since

January 2010 are on an annual basis beginning and ending the

month joined. All renewals are due before the expiration date which

can be found on the label of Paper Money. Renewals may

be done via the Society website www.spmc.org or by check/money

order sent to the secretary.

December 2015 with final dates to be determined -

Day 1 : The Alexander I Pogrebetsky Auction, Part 2 of Chinese, Asian and Russian Banknotes

Day 2 : U.S. & Worldwide Banknotes, Scripophily, Coins and Ephemera

Day 3 : Live Internet & Absentee Bidding Sale of U.S. & Worldwide Banknotes, Scripophily & Coins

Alabama State Fractional Currency:

Printing Sequence and a Variant of the 50 Cent Note

by Charles Derby

The first issue of notes printed by the state of Alabama during the Civil War includes

fractional notes of the denominations $1, 50 cents, 25 cents, 10 cents, and 5 cents, all bearing

the printed date of January 1st 1863. The story of their production is told by Milo Howard,

former director of the Alabama Department of Archives and History and president of the

Alabama Historical Society, in his 1963 paper in Alabama Historical Quarterly. These notes

were authorized by acts of the Alabama legislature on November 8th and December 4th 1862 in

the amount of $3.5 million. Governor John Gill Shorter then contracted with prolific Southern

printer J. T. Paterson & Co. to produce these notes.

The 50 cent notes have two vignettes (Fig. 1). The central vignette is of a tree with a map

of Alabama at its base. In the center of the note, below the tree vignette, is a distinctive blue “50

Cts” protector. At the bottom right of these notes is a portrait of Juliet Opie Hopkins, who was a

member of the husband-and-wife pair in charge of the hospitals in Alabama during the Civil

War (Harper, 2003). Judge Arthur Francis Hopkins oversaw the entire operation, while Juliet

oversaw civilian aid and donations.

These 50 cent notes consist of three types, designated according to their series of

production (Fig. 1). The first type has no series designation on the note; it is called “No Series”

by both Criswell (1992) and Shull (2006) and is identified by them as Cr3. The other two types

of 50 cent notes are designed by “2nd SERIES” printed vertically at the lower right end of the

note, to the left of the image of Juliet Hopkins. These two types differ in the size of the lettering

of 2nd SERIES. In the small-lettered 2nd SERIES, the 2nd SERIES is about 10 mm or 3/8 inch

long, or equivalent to the length of Mrs. Hopkins’ head, from the crown to chin. In the large-

lettered 2nd SERIES, the 2nd SERIES is about 50% longer than in the small-letter series, or 15

mm or 9/16 inch long, which is the length from the crown of Mrs. Hopkins’ head to the bottom

of the shawl below her chin. Criswell (1992) and Shull (2006) designate the small-lettered 2nd

SERIES as Cr4 and the large-lettered 2nd SERIES notes as Cr4B.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

384

Figure 1. Fifty-cent Alabama Treasury notes of 1863. Top, AL-Cr3 No series. Middle, AL-

Cr4B 2nd SERIES in large letters. Bottom, Cr4 2nd SERIES in small letters.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

385

The Sequence of Printing of the 50 Cent Notes

The No series 50 cent notes, which lack a series designation on them, were printed first,

before the 2nd Series. Why were these notes not given a series designation? In fact, of this first

issue, the $1, 10 cent, and 5 cent notes all have representatives with “1st SERIES” printed on

them. But the 50 cent and 25 cent notes do not. Howard (1963) explained why. Governor

Shorter’s first order of fractional notes was for $2.5 million of the authorized $3.5 million.

Shorter received the first notes from Paterson in January 1863, and he noticed that the 50 and

25 cent notes lacked the series designation. Shorter wrote Paterson on March 17th 1863 that

these notes should be considered “1st series” and that plates that Paterson produced from then

on should be numbered as series “No. 2 up.” Thus, when Shorter ordered the remaining $1

million in fractional notes, the 50 and 25 cent notes bore series designations. From this account

by Howard (1963), we know that the No Series 50 and 25 cent notes are actually 1st SERIES.

Howard (1963) did not explain, nor did Criswell (1992) or Shull (2006) or anyone else to

my knowledge, why there are two 2nd SERIES sizes, or what was the order of sequence in

printing of these notes. I offer the following data on ranges of serial numbers, which show that

the large-lettered 2nd SERIES was printed before the small-lettered 2nd SERIES.

The State Auditor’s Record in The Register of Alabama State Treasury Notes, as reported

by Howard (1963), shows the number of sheets of 50 cent notes produced. The No Series/1st

SERIES sheets were numbered 1 to 24478, and the 2nd SERIES 1 to 82191. I have catalogued

large-lettered 2nd SERIES notes numbered from 344 to 17456, and small-lettered 2nd SERIES

notes numbered from 16818 and above. These data, together with Howard’s information, show

that Paterson first produced 24478 sheets of No series/1st SERIES, then about 17 thousand 2nd

SERIES sheets using large lettering, followed by about 66 thousand sheets of small-lettered 2nd

series notes. Thus, an overlap in numbering of the large and small 2nd SERIES of several

hundred notes occurred during issuing.

The 25 cent notes follow a similar pattern. These notes included a “No series,” two types

of “2nd SERIES” (small and large lettered, as in the 50 cent notes), and a “3rd SERIES” (Fig. 2).

Howard (1963) reported that The Register of Alabama State Treasury Notes recorded that the

No Series/1st SERIES had sheets numbers 1 to 26371, the 2nd SERIES had sheets 1 to 84370, and

the 3rd SERIES was 1 to 35927. These are designed by Criswell (1992) and Shull (2006) as Cr 5,

6, 6A, and 7, respectively. My catalogue of the large-lettered 2nd SERIES shows numbers 147 to

15856, and the small-lettered 2nd SERIES runs from 15965 and up. Thus, these data on 25 cent

notes are consistent with a conclusion that J. T. Paterson produced 26371 No series/1st SERIES

sheets, then about 15900 large-lettered 2nd SERIES sheets, followed by about 68 thousand

small-lettered 2nd SERIES sheets. Then, for the 3rd SERIES, Paterson produced nearly 35

thousand of these notes. This is the same pattern as for the 50 cent notes.

There are some minor points of interest with the 25 cent notes. Low numbered No

series/1st SERIES notes are relatively rare. Records of the Alabama Registry show that the

Comptroller had a policy of destroying old and mutilated change bills, and a total of $377,493.05

was burned, including $71,840.50 of 50 cent notes and $180,956.50 of 25 cent notes (Howard,

1963). This could account for why the earliest, low numbered 25 cent notes are rare today.

Another interesting point is that there was an error in production of a short run of the small-

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

386

Figure 2. Twenty-five cent Alabama Treasury notes of 1863. Top left, AL-Cr5 No series. Top right

AL-Cr6A 2nd SERIES in large letters. Middle left, AL-Cr6 2nd SERIES in small letters. Middle right,

AL Cr6B 2nd SERIES in small letters but with 22nd instead of 2nd. Bottom, AL-Cr7 3rd SERIES.

lettered 2nd SERIES notes. In this error, a second “2” was added, making it appear as “22nd

SERIES” (Fig. 2). Criswell (1992) and Shull (2006) identify these as Cr6B. My records show

these to have occurred in a run from 52310 to 52318, and given that Shull lists them as Rarity 8,

or 51 to 100 extant notes, the run must extend outside of the numbers I list above.

In conclusion, the patterns of serial numbers are the same for the series of 50 cent notes

and the series of 25 cent notes, demonstrating that in both denominations, the large-lettered 2nd

SERIES notes were printed before the small-lettered ones.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

387

Figure 3. Green eagle variety of the 50 cent Alabama Treasury note of 1863. Shown are four examples.

The bottom two notes are courtesy of Heritage Auctions.

Figure 4. The eagle vignette, shown from the same note in its regular color form (left) and as a

black-and-white contrast for a better visualization of the vignette (right).

Discovery of a New Type of 50 Cent Note: Cr4 with green eagle

I have seen four examples of an unusual version of 50 cent notes (Fig. 3).

What are the features of these notes?

1. The vignette. By transforming the image from color to high-contrast black-and-white, one

can more clearly see the subject of the vignette (Fig. 4). It is an eagle, sitting on its eyrie, with

two hungry eaglets ready to be fed.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

388

Figure 5. Four other notes bearing the identical eagle vignette.

2. Serial numbers and block letters. The notes are close in serial number: 59146, 59147, 59200,

and 59551. I have not seen any notes between 59000 and 60000 that do not have this

vignette. I have seen notes as high as 58944 and as low as 60170 that do not have the

vignette. Thus, these notes are in the middle of the small-lettered 2nd SERIES run. The four

notes in Figure 3 have different block letters: E, F, G, and O. According to William Gunther

and Howard (1963), these 50 cent notes were printed in sheets of 15 notes, with three

columns and five rows, and with all notes on a sheet having the same serial number. The

block letters were A to O, with A, B, and C in the first row, D, E, and F in the second row, and

so on. Given this, it is reasonable to assume that these notes with green eagles were printed

by J. T. Paterson for the State of Alabama, in a run of at least 405 and as many as nearly

1000 sheets, and with all block letters on each sheet having the vignette.

3. Printed image: The green eagle is printed rather than stamped.

4. Location of the vignette on the note: The eagle vignette is not in the exact same location on

the note, much as the blue “50 Cts” overprint varies in placement. Its location on the 59146

and 59147 notes is almost identical, but the location on the 59200 and 59551 notes is

different from each other and different from 59146 and 59147. The similar position of the

59146 and 59147 notes might be expected given they were on consecutive sheets.

Is this eagle vignette unique to this note? This eagle vignette is rare but has been used before

and after this Alabama note. I have seen other examples of it, seven shown here, counting the

Alabama note: two appeared before the Alabama note; three after it; and one contemporaneous

with it. The vignette in these seven note types appears to be absolutely identical, and not

independently produced copies of the same image, as was often the case in cheaply made notes

during the Civil War era. These notes are shown in Figures 5 and 8.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

389

South-Western Bank of Virginia, $1, Wytheville, VA. This note has two varieties, differing in the

printed date. The May 1st 1861 variety is BW60-05 (Littlefield and Jones) and VA-270-G10

(Haxby), and the July 1st 1861 variety is BW60-06 and VA-270-G10a. The imprint reads “St.

Clair, Printer, Wytheville, VA.” The South-Western Bank was originally named the Bank of

Wytheville, authorized on May 11, 1852, by the Virginia General Assembly. Its name was

changed to South Western Bank of Virginia on February 16, 1853” (Littlefield and Jones, 1992).

D. A. St. Clair, with his St. Clair Press and St. Clair’s Power Press, was a prolific printer,

including of documents, books, and newspapers (including the Wytheville Dispatch). He was a

frequent printer of currency in Virginia, particularly in western and southwestern Virginia, for

banks, cities, counties, and private businesses. These include The County Court of Bland County,

County of Pulaski County, Smyth County, Wise County, Wytheville, The Farmers Bank of

Fincastle, The Hillsville Savings Bank of Hillsville, North Western Bank of Virginia in

Jeffersonville, and South Western Bank of Virginia. The Federal government was well aware of

St. Clair’s production of Southern currency, so much so that when Federal troops raided

Wytheville, his Wytheville Dispatch printing shop and house were specific targets of the raid

(Walker, 1985).

Corporation of Fort Valley, NC, 10 cents. This note is NC FV (X)-10 and is dated July 2, 1861.

This is a spurious note that is part of a series, with representatives from South Carolina, North

Carolina, and Tennessee. The others in the series are from the Corporation of Charleston,

Corporation of Columbia, Corporation of Branchville, and Corporation of Cheraw in South

Carolina, and the Corporation of Chattanooga in Tennessee. Austin Sheheen (1960) wrote that

the South Carolina notes “are believed to be either contemporary with the periods indicated or

very shortly afterwards. There was no authorization for their issue and they were probably

issued for patriotic reasons. They can be classified as bogus." Horner and Roughton (2003)

pointed out that the Fort Valley NC note is part of this series, although it, unlike the others is not

from a real town or city. They also wrote that all these notes are “spurious notes

and…contemporary with the period, namely issued during the Civil War to deceive the

recipient of these bogus notes.” Garland (1992) wrote that the Corporation of Chattanooga notes

“could be a fantasy note.” There is no imprint on any of these notes and thus the printer is

currently unknown.

P. Palmer & Co., Chicago, Illinois, 50 cents. This note (IL-900-25) is dated 186_ and bears the

imprint of “ROUNDS, PRINTER, 46 STATE ST.” A 25 cent note that is otherwise identical to

this 50 cent note also exists. P. Palmer & Co. was a small enterprise when this note was printed,

but it grew into a business that is well known today. Potter Palmer established a dry goods store

in Chicago in 1852. Palmer merged his business with his brother (Milton Palmer) and two

owners of another dry goods store (Marshall Field and Levi Leiter) in 1865, forming Field,

Palmer, Leiter & Co. The Palmers left the business in 1867, but Potter, who since had focused on

real estate, leased a grand building, the Marble Palace on State and Washington streets, to the

business, now named Marshall Field & Company and typically called Marshall Field’s. This

upscale department store grew from its Chicago roots to become a major chain, until it was

acquired in 2005 by another major department store, Macy’s (from Wikipedia). Sterling Parker

Rounds was an active printer in Chicago beginning in the 1850s, in association with James J.

Langdon (Andreas, 1884). He seemed not to have printed an abundance of paper money, but he

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

390

Figure 6. The eagle vignette from different notes. Top, Alabama Cr4D, 50 cents, 1863

(modified to be a black-and-white, high-contrast image so as to see the features of the

eagle). Middle left, South-Western Bank of Virginia, $1. Middle right, Corporation of

Fort Valley, NC, 10 cents. Bottom left, P. Palmer & Co., 50 cents. Bottom right, The

Findlay Belt Railway Company, $100 stock certificate.

is known to have printed at least one other: Geo. Glick, Marshalltown, Marshall County, PA,

Oakes 39-1, 5 cents, Nov 1862. Imprint: Rounds Printer, 42 State St., Chicago.

$100 stock certificate of The Findlay Belt Railway Company, Ohio. This stock certificate has a

printed date of 189_ on the back and signed date of 29th of March 1924 on the front. The

company was incorporated in Ohio on April 1, 1887, to build a railroad in and around Findlay,

Ohio (from Wikipedia). Financial documents in the form of a cash book and minutes of

meetings of the board of directors and stockholders exist for 1887 to 1913, and a map of The

Findlay Belt Railway route in 1915 exists.

N.Y. Central Academy Bank, $1. A new example of this vignette was listed in the Jan./Feb. 2015

issue of Paper Money (Gill, 2015). This college currency bank note from McGrawville, NY, was

printed by L. C. Childs of Utica, NY, and dated August 1864.

What are the features of these notes with this eagle vignette?

The eagle image is identical in form and size in these notes, as is apparent from Figure 6.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

391

Figure 7. A later variant on the eagle vignette.

Figure 8. Georgia 50 cent treasury note, contemporaneous with the Alabama 50-cent

treasury note with the identical green eagle vignette (courtesy of Mack Martin).

A variant of this eagle-on-nest vignette also exists. It is found on two notes, both printed by

Hatch & Co. These are: Baltimore National College Bank, $100, Baltimore, MD-175; and

Buckeye Business College Bank, $10, Sandusky, OH OH-1000-100. This Hatch is not the famous

one who partnered with others to form the big bank note companies. Hatch & Co. was a smaller

operation in New York City that printed money in the 1870s from the Trinity Building.

Georgia Fifty Cent Treasury Note with the Identical Green Eagle Stamp

A recent discovery provides new insight into the Alabama note. This is a contemporaneous 50

cent Georgia treasury note (GA-Cr14, or ML-12), shown in Figure 8. This note has the identical

date as the Alabama note: January 1st 1863. However, it was not produced by J. T. Paterson, but

rather by the Georgia state printer and engraver Richard H. Howell of Savannah (Martin and

Latimer, 2005).

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

392

What is the origin of the green eagle vignette of the Alabama notes?

Was this note a counterfeit? Everything else about this Alabama note indicates that it is

authentic. The handwritten serial numbers are very similar in style to those on authentic notes.

Their serial numbers fall perfectly in sequence with the other notes. The same is true for the

Georgia 50 cent note. An argument against them being counterfeits is that by mid-1862,

inflation was already high and there would have been little incentive to counterfeit change notes

like this 50 cent note. Furthermore, adding this green eagle vignette would have drawn

unnecessary attention to the notes.

The presence of this green vignette on both the Alabama and Georgia notes argues that they

were not placed on the note by the printers, Paterson for the Alabama note and Howell for the

Georgia note. This argues that someone other than the printers added the vignette after their

production. Why that would have been done is unclear. Is this note in some way connected to

the other three note types with this same vignette that were produced during the Civil War? The

vignette is clearly identical in all of these note types. But the production of the different note

types seems unconnected, by either their printer or location of production. They were printed by

at least five printers (J. T. Paterson, R. H. Howell, S. P. Rounds, D. A. St. Clair, and L. C. Childs,

with the printer of the Corporation of Fort Valley note currently unidentified) and in at least six

states (Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, New York, North Carolina, and Virginia). At least two of the

notes (South-Western Bank and Corporation of Fort Valley) and possibly a third (P. Palmer &

Co.) preceded the Alabama note. So, at present, the origin of and reason for this green eagle

vignette remains a mystery.

References

Andreas, Alfred Theodore. 1884. History of Chicago. A.T. Andreas, Publisher: Chicago, IL.

Criswell, Grover C., Jr. 1992. Confederate and Southern States Currency: A Descriptive Listing, Including Rarity

and Values. BNR Press: Port Clinton, OH.

Gill, Robert. 2015. A rare college currency bank. Paper Money Jan./Feb. 2015, No. 295: 42-43.

Harper, Judith E. 2003. Women during the Civil War: An Encyclopedia. Routledge: New York.

Horner, Paul and Roughton, Jerry R. 2003. North Carolina Numismatic Scrapbook, Vol. 1, No. 9: p. 9.

Howard, Milo B., Jr. 1963. Alabama State Currency, 1861-1865. Alabama Historical Quarterly 25: 70-98.

Littlefield, Richard and Jones, Keith. 1992. Virginia Obsolete Paper Money. Virginia Numismatic Association:

Annandale, VA.

Martin, W. Mack and Latimer, Kenneth S. 2005. State of Georgia Treasury Notes, Treasury Certificates, and Bonds.

A Comprehensive Collector’s Guide. Printed by the authors.

Sheheen, Austin M., Jr. 1960. South Carolina Obsolete Notes. The First Comprehensive Listing of State, Broken

Bank, Town, City, Railroad and Miscellaneous Other Notes. A. M. Sheheen Jr.: Camden, SC.

Shull, Hugh. 2006. Guide Book of Southern States Currency. History, Rarity, and Values. Whitman Publishing:

Atlanta, GA.

Walker, Gary C. 1985. The War in Southwest Virginia 1861-65. A&W Enterprise: Roanoke, VA.

Acknowledgment.

I thank Bill Gunther for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript, and Mack Martin for providing the

image of the Georgia note in Figure 8.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

393

The Paper

Column

Mono-Color 18-Subject Overprinting Operations

Created Distinctive Errors on

$1 Series of 1935D and E Silver Certificates

by

James Martin

Peter Huntoon

Bob Liddell

Jamie Yakes

Derek Moffitt

Doug Murray

The purpose of this article is to examine a group of unusual $1 silver certificate overprinting errors

that were produced between July 1952 and April 1954. They were made during a brief period when Series

of 1935D and E notes were overprinted on two separate presses, one for the black Treasury signatures and

series and the other for the blue seals and serial numbers. The result was creation of a suite of dramatic errors

that simply aren’t possible on more modern notes.

Similar errors were possible on Series of 1929 national and Federal Reserve bank notes and World

War II brown and yellow seals because those notes also required passes through two different overprinting

presses. Consequently if you want to collect these varieties, you have to reach back into the past for

specimens. The $1 Series of 1935D and E offer the most fertile ground.

This is a tale of machinery; specifically, 18-subject flatbed presses purchased by the BEP for use on

an interim basis to overprint notes when the sheet size was increased from 12- to 18-subjects. The use of this

equipment provided breathing room for BEP personnel to design and have built 18-subject bicolor rotary

overprinting presses that ultimately took over the job.

The overprinting presses that created the errors described here consisted of flatbed mono-color

presses purchased in July 1952. Pairs of these presses were used in tandem to overprint first the black series

and Treasury signatures, and second the blue seals and serial numbers. Information available to us in the form

of errors that are peculiar to this equipment reveals that the tandem mono-color presses were used exclusively

for the production of 18-subject $1 Series of 1935D and E silver certificates.

Additional 18-subject bicolor flatbed presses were purchased later in 1952 that affixed both

overprints in one pass. They were used to overprint all the other classes and denominations of notes that were

then current. They could have been used to supplement $1 silver certificate production but we have found

no records that demonstrate such use. The bicolor presses could not produce the errors that are the subject

of this article.

Both the mono- and bicolor presses were used until April 1954, when newly designed 18-subject

bicolor rotary overprinting presses replaced them.

Signing Currency

The hand signing of U. S. currency by Treasury officials went out of favor early in the large note

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

394

era. The volumes of currency that required signatures precluded it.

The signatures on most large size notes were printed facsimiles that were incorporated directly into

the engravings on the intaglio printing plates. Signature samples were provided to the engravers, who in turn

reproduced them on dies. Next, rolls were made from those dies and used to transfer the signatures to the

necessary printing plates as many times as needed.

The practice of putting the signatures on the plates was passed down to small size production in

1928. However, in the case of small size notes, the signatures were rolled into the master dies rather than

being rolled in separately on the plates.

There was a downside to placing the signatures on the face plates, and that was the problem caused

when one or both Treasury officials left office. New signatures were required, but the old were part of the

plates so they couldn’t be changed without altering the plates.

There were three ways plates with obsolete signatures were handled during the large note era. Most

continued to be used until they wore out. Others were scrapped. The signatures were changed on some, a

practice that usually was reserved for low-production plates, especially those for the high denominations.

Signatures never were changed on the plates used to print small size notes.

The idea of overprinting signatures and series was not new. The concept already had passed the test

on Series of 1929 national and Federal Reserve bank notes because the bank information and signatures were

overprinted on them. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing began an 18-year program to convert all their

currency production to overprinted signatures beginning in 1935.

Initially the overprinting of the Treasury signatures and series was restricted to 12-subject $1 Series

of 1935 sheets. They were earmarked for the innovation because they were produced in such large volumes.

Eventually the technology spread to other classes and denominations, first to the 12-subject Series of 1950

Federal Reserve sheets, and later to the 18-subject Series of 1953 legal tender and higher denomination silver

certificate sheets.

Practices evolve, so once again the BEP incorporated the treasury signatures on the intaglio face

plates beginning in 1968 with the $100 Series of 1966 legal tender notes, a situation that prevails to the

present. The modern generation of rotary overprinting presses are still bi-color because the black district

seals and identifiers continue to be overprinted on Federal Reserve notes.

Overprinting Presses

The Bureau went through successive generations of overprinting presses to apply the series, treasury

signatures, seals and serial numbers. Beginning in 1935, they used newly configured bicolor rotary presses

that allowed all of these elements to be printed in one pass through the press.

The presses handled 12-subject sheets, wherein the notes were numbered consecutively down the

half sheets using different groups of consecutive numbers on each side. A knife in the press slit the sheets

in half after the overprints were applied. Next knives in the machine separated the notes from the respective

halves and the notes were mechanically collated in correct numerical order (Hall, 1929, p. 112-113).

Exceptions were made to the one-pass printing of overprints on the World War II yellow and brown

seals owing to the limitations of the bicolor presses. The yellow seals required an extra printing to apply the

yellow seals. Similarly the Hawaii notes required additional printings to apply the HAWAII’s to their faces

and backs.

The transition to 18-subject plates was announced by the BEP in April 1952 (Hall, 1952, p. 1) and

the first notes affected were $1 Series of 1935D silver certificates. Experimental 18-subject $1 plates were

certified in May 1952 (BEP, various dates) and sent to press on June 16th (Hall, 1952, p. 58).

The changeover from 12- to 18-subject production was not abrupt. Instead 18-subject production was

ramped up on $1 silver certificates while 12-subject production was gradually wound down. The first $1

silver certificate18-subject face and back production plates were certified respectively on July 11 and 10,

1952, whereas the last 12-subject face and back plates were certified September 10 and October 14, 1952

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

395

(BEP, various dates). Use of the 12-subject plates in all classes and denominations continued to September

1953.

The Bureau did not possess 18-subject bicolor overprinting presses at the beginning of July 1952,

so a pair of mono-color typographic cylinder flatbed presses was purchased to accommodate overprinting

of the $1 silver certificates on an interim basis (Hall, 1952, p. 1). They were operated in tandem, one for each

overprinted color. The cylinder on each press was an impression roller that pressed the sheet against the flat

bed of the press, which contained the inked elements. Five of these presses were in operation by July 1953

(Hall, 1953, p. 42-43).

One implication of this is that 36 serial numbering registers were mounted in or on the flat bed of

the blue press along with the 18 seals. A press of similar design had been used to seal and number 4-subject

national bank note sheets between 1926 and 1929 (Hall, 1926, p. 6-7).

The first recorded use for the tandem flatbed presses available to us involved the overprinting of $1

Series of 1935D star notes on July 29, 1952 when the *00000001D note was printed (BEP, undated). The

GG serial number block was assigned to the first 18-subject regular production with first deliveries to the

Treasury on November 20, 1952 (Hall, 1953, p. 65) followed by the NG block.

The BEP purchased five bicolor flatbed cylinder presses during the latter part of 1952 to handle

additional 18-subject production as other denominations and classes of currency were converted to 18-subject

format (Hall, 1953, p. 42-43). Of course, the appeal of the bicolor presses was that both colors could be

applied simultaneously on the same press. The first delivery from the bicolor presses occurred on April 3,

1953 and consisted of $10 Federal Reserve notes (Hall, 1953, p. 65).

All currency regardless of class or denomination was being produced from 18-subject plates by

September 1953 (BEP, 1962, p. 159). Use of the flatbed overprinting presses, both tandem mono-color and

single bicolor, to overprint the 18-subject stock ceased in April 1954, having been supplanted by production

from newly installed 18-subject bicolor rotary presses.

The first of sixteen newly designed 18-subject bicolor rotary overprinting presses came on line in

March 1954. This one-pass overprinting capability, coupled with the greater speed of rotary presses,

materially increased production rates. These machines arrived fairly early during the Series of 1935E $1

silver certificate era so most of the Series of 1935E notes were numbered on them.

The last batch of Series of 1935E star notes printed on the tandem flatbed presses consisted of

4444-8/18 sheets bearing numbers *61120001D-*61200000D, which were numbered on April 1, 1954. That

printing had been preceded by rotary press star printings, the first of which occurred on March 20th, so there

was a transition period lasting at least 10 days when the flatbed and rotary overprinting presses were in use

(BEP, undated). All sixteen of the new 18-subject rotary overprinting presses were in operation by April

1954 (Holtzclaw, 1954, p. 92).

All18-subject sheets, regardless of press, were numbered consecutively through the stack rather than

down the half sheets. Consequently consecutive notes had the same plate position letter rather than cycling

through the letters on a given half sheet as before. The notes generally were numbered in production units

of 8,000 sheets (144,000 notes) so serial numbering advanced by 8,000 between the subjects on a given sheet.

Neither the 18-subject flatbed nor new bicolor rotary presses possessed the capability to cut the notes

from the sheet in contrast to their 12-subject rotary predecessors. The notes had to be cut by guillotine as a

separate operation.

A lone surviving proof exists in the Smithsonian holdings from an experimental 18-subject black

overprinting plate made during the flatbed era. It is labeled as being an experimental high-etched topographic

plate that was certified October 2, 1952, two and a half months into 18-subject tandem flatbed production.

The fact that it was certified reveals that it most likely was used to overprint the Treasury signatures on

issued Series of 1935D notes. Figure 1 illustrates part of that proof.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

396

Figure 1. The overprint for one subject from an 18-subject proof lifted from an experimental high-etched

overprinting plate employed on an 18-subject mono-colored topographic overprinting press used to apply the

black overprint to Series of 1935D silver certificates. The plate was certified November 1, 1952. Plate number

51709 shown in the inset is from a set of numbers used for photo-litho plates.

Mono-Color Press Errors

The overprinting of the 18-subject 1935D and early 1935E silver certificates on tandem pairs of

mono-color presses is of supreme importance to error collectors. Error permutations were produced that had

not been seen since the Series of 1929 and the WW II issues.

The distinguishing characteristic of the unusual errors is that the problem involved only one of the

two overprinted colors, demonstrating that the problem was confined to only one of the two presses. An

excellent example is a note with normally printed black signatures and series but inverted blue serial numbers

and seal. This error is impossible from either a bicolor flatbed press or bicolor overprinting press.

These strange errors occur on $1 SC faces bearing plate serial numbers from 7469 to about 8000.

They were made in the window between July 1952 and April 1954 when tandem mono-color flatbed presses

were used to overprint the notes. All the observed errors have serial numbers with a G suffix, although it

appears that the AH and BH blocks also could have been affected.

There are eight distinctive permutations that are specific to the $1 notes produced during this

interesting period.

1. Mono-color inverted overprints, such as

(a) inverted signatures and series but not seals and serials,

and (b) inverted seals and serials but not signatures and

series.

2. Missing mono-color overprints, such as

(a) no signatures and series but normal seals and serials,

and (b) no seals and serials but normal signatures and

series.

3. Mono-color overprints on the back, such as

(a) signatures and series only on the back, or

(b) seals and serials only on the back.

4. Skewed overprints involving only one color, such as

(a) skewed signatures but not seals and serials, and

(b) skewed seals and serials but not signatures and series.

Not included in this list are very peculiar but innumerable printed creases and foldover oddities that

affected only one of the overprinted colors! An example would be a folded over lower right corner upon

which part of the seal and right serial number ended up on the back of the note, but not the series and

Treasury signatures.

We are illustrating six examples of these errors. Notice how each involves only one color.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

397

Figure 2. This is a

Series of 1935D note

based on its serial

number. The black

o v e r p r i n t w a s

somehow omitted

when the sheet was

fed through the black

overprinting press,

probably by being

covered by another

sheet stuck to the top

of it.

Figure 3. An inverted

blue but normal black

overprint could occur

only if the blue

overprint was applied

on a separate press.

T h i s n o t e w a s

numbered in January

1954.

Figure 4. An inverted

black but normal

blue overprint could

occur only if the

black overprint was

applied on a separate

press.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

398

Figure 5. The fact

that only the blue

items in the overprint

are shifted reveals

that the blue part of

the overprint was

applied on a separate

machine, something

not possible on

bicolor flatbed or

rotary overprinting

presses where both

colors are applied

simultaneously.

Figure 6. A significant

upward shift of the

Treasury signatures

and series reveals that

the black part of the

overprint was applied

o n a s e p a r a t e

overprinting press.

This type of error is

confined to the period

1952-4 when the

different colors were

o v e r p r i n t e d o n

separate presses.

Figure 7. The left shift

of the Treasury

signatures and series

independently of the

blue serial numbers

and seals is a

characteristic of

errors produced

during 1952-4 when

the different colors

were overprinted on

separate presses.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

399

Figure 8. This

spectacular foldover

error sports blue

seals and serials that

ended up on the back

of the note. Later in

the series, when both

the black and blue

overprints were

applied together on

bicolor overprinting

presses, the black

Treasury signatures

and series would

accompany the seals

and serials numbers

on the back of such

foldovers. The fact

that they don’t

reveals that tandem

m o n o - c o l o r

overprinting presses

were used, one for

each color.

Perspective

All error collecting is like this. If you don’t understand the machines and processing, how can you

fathom the errors? Equally important is how can you protect yourself from the fake errors that are being

cranked out to separate you from your money these days?

A disclaimer is in order. We have concluded based on observed errors that the tandem mono-color

flatbed overprinting presses appear to have been used exclusively to print $1 silver certificates and the

bicolor flatbed overprinting presses appear to have been used for all the other denominations and classes.

There is no technological reason why either of these press configurations couldn’t have been used to print

any 18-subject sheet. In time we may discover that some $1 silver certificate press runs were made on the

flatbed bicolor presses or some of the other denominations and classes were overprinted by tandem mono-

color flatbed presses. If the latter occurred, evidence should reveal itself in the form of the peculiar errors

profiled here on notes other than $1 silver certificates.

Credits

This article was a team effort. The special characteristics of the errors described here were first

recognized by James Martin several years ago. Peter Huntoon provided the technical explanations. Bob

Liddell supplied all the illustrations, except Figure 2, which came from Heritage Auction archives. Doug

Murray provided a serial number ledger for $1 Series of 1935D and E star note production. Derek Moffitt

and Jamie Yakes provided crucial documents and insights based on their research into serial numbering

during the startup of the 18-subject era that both fleshed out and constrained the findings provided here.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

400

References Cited

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1962, History of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, 1862-1962: U.

S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 199 p.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, various dates, Certified proofs of intaglio printing plates: National

Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution,

Washington, DC.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing, undated, Ledger showing serial number press runs for $1 Series of 1935D

and E silver certificates: Bureau of Engraving and Printing Historical Resources Center, Washington,

DC.

Hall, Alvin W., 1926, Annual Report of the Director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing: Government

Printing Office, Washington, DC, 22 p. plus appendices.

Hall, Alvin W., 1929, Annual report of the Director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing: U. S.

Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 30 p. plus appendices.

Hall, Alvin W., 1952, Annual Report of the Director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, fiscal year

ended June 30, 1952: Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Washington, DC, 115 p.

Hall, Alvin W., 1953, Annual Report of the Director of the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, fiscal year

ended June 30, 1953: Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Washington, DC, 87 p.

Holtzclaw, Henry J., 1954, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, p. 87-96; in, Annual report of the Secretary

of the Treasury on the state of the finances for the fiscal year ended June 30, 1954, U. S.

Government Printing Office, Washington, DC, 781 p.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

401

THE FIRST ISSUE OF BANK OF ISRAEL NOTES PROVED

UNPOPULAR WITHIN THEIR COUNTRY OF ISSUE

Carlson R. Chambliss

In my opinion the 1955 issue of Israeli banknotes, which was the first of the note issues

of the Bank of Israel, is by far the most attractive of the various issues of Israeli paper money.

This series had been preceded by issues of the private Anglo-Palestine Bank (in 1948) and Bank

Leumi Le Israel (in 1952). Both of these were products of the American Bank Note Co. in New

York, and for designs they made use of a rather unimaginative combination of guilloches that

were taken from stock designs that the ABNCo had on hand. Indeed the 1948 series was

produced under emergency conditions, but the designs proved to be popular with Israelis, and so

the same basic designs were continued with the 1952 series that very closely resemble their

counterparts of 1948.

The Bank of Israel was organized in 1954, and it soon acquired total control over the

production and distribution of all coins and banknotes in the State of Israel. The executives of

this organization turned to the venerable British firm of Thomas de la Rue & Co. for the design

and production of their first issue of banknotes. All of these notes carry a date of 1955 or 5715

in the Jewish religious calendar. They also carry two signatures, those of David Horowitz as

governor of the Bank of Israel and that of Siegfried Hoofien, who was then serving as Chairman

of the Advisory Council to the Bank of Israel. Mr. Hoofien was no stranger to the production of

banknotes for Israel. During the 1940s he was the general manager of the Anglo-Palestine Bank

and had overseen the production of both the 1948 and 1952 issues of banknotes that were still

issued by the private Anglo-Palestine Bank, which was re-named the Bank Leumi Le Israel

(National Bank of Israel) in 1950. His signature had appeared on both of these series of notes

and also on the emergency series of notes that were clandestinely printed in Israel during the

spring of 1948 but were never issued.

The Series 1955 Bank of Israel notes are often referred to as the Landscapes series, since

their faces do indeed depict landscapes or historic scenes from various parts of Israel. All are

printed by high relief intaglio which contrasts rather sharply with the low relief intaglio that was

employed by the ABNCo on the 1948 and 1952 issues. Lithography as also used to produce the

underlying pastel shades on these notes, and the overall effect is most attractive. All of the notes

also display an image of a flower and a menorah watermark in their upper right corners along

with a vertical security thread. So far as I know, these notes were never counterfeited. The

denominations were the same as those used for the 1948 and 1952 issues, viz., a half lira (500

prutah) together with 1, 5, 10, and 50 lirot.

By the mid-1950s the Israeli economy had finally achieved a degree of stability, and the

multiple exchange rates that were characteristic for the Israeli currency during the first few years

of independence were now a thing of the past. During the period in which these notes were in

use the exchange rate stood at about 1.80 to the US dollar, thus making each Israeli lira worth

about 56 cents. Thus the face values of these notes ranged from some 28 cents to about $28 in

US currency at that time. By the 1970s inflation was again to become a serious problem in

Israel, but for the time being in the late 1950s a degree of stability did prevail.

The 500 prutah note is predominantly red in color. There is also an underprint in light

bluish green on its face, and its back also includes a vivid underprint of greenish blue. It depicts

the ruined Bar’am Synagogue in northern Galilee that dates from the third or fourth century AD.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

403

This note measures 130 x 71 mm, and a cyclamen flower is depicted in its upper right along with

a menorah watermark.

The one lira note is somewhat larger, measuring 135 x 74 mm. It depicts a landscape

from upper Galilee with the Jordan River in the foreground. It is predominantly blue in color but

with shading in rose and yellow-orange. The flower depicted is an anemone. The 500 prutah

note was first issued on August 4, 1955, although the one lira note was not released until October

27th of that year.

One might expect that the half lira and one lira notes would have by far the largest

printings for this issue, but my research indicates that only about 18 million of each were printed.

In terms of face value less than 5% of the total value for this series was printed for these two

denominations. Today these notes are scarce when in uncirculated grade, and they are less

common than one might think when in VF condition or better.

The ruined synagogue at Bar’am in

northern Galilee is featured on the 500

prutah value of this issue. In this

specimen set the word “Specimen”

appears in sans serif capital letters, but

specimen notes are also known with

double-lined letters.

The one lira note depicts a settlement in Upper Galilee with the Jordan River in the foreground. The De La

Rue ovals and the word “Specimen” appear on both sides of the specimen notes. The wording “no value”

refers, of course, to the legal tender or face value of these notes. Their numismatic value, of course, is quite

substantial.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

404

The five lirot note measures 140 x 78 mm and is predominantly brown in color. The face

design also includes substantial toning in light blue, and vivid shading in yellow and light blue is

used on the back side. Depicted is a landscape from the mostly desert Negev region which

shows signs of agricultural development. The flower depicted at the upper right is an iris. As is

the case with the two lower values the serial numbers are printed in black, and by my estimate

the total number of notes printed was about 20 million. This note was released at the same time

as the one lira value of this issue.

The ten lirot note depicts an agricultural scene in the Jezreel Valley region of southern

Galilee. Much of this valley lies below sea level, but it is a rich agricultural zone. This note

measures 150 x 82 mm in size and it is predominantly green in color. Subtle shading is done in

light green, orange, and rose. The flower depicted at the upper right is a tulip. This note was

printed in larger quantities than were any of the other denominations, and it remains the most

abundant of the notes of the 1955 issue. Since there are 22 letters in the Hebrew alphabet,

apparently 22 million of these notes were printed with red serial numbers. Then a new sequence

of these notes was printed with black numbers and letters. This sequence was also largely

completed, and my estimate for the total printing of ten lirot notes for the 1955 issue is about 42

million notes. This also makes this denomination the most abundant in today’s market for notes

of the 1955 series. This note was released at the same time as the 500 prutah note of this issue,

but notes with black serial numbers did not appear until June, 1958.

The five lirot note depicts a scene in the Negev region of Israel. Under Israeli management some of this

mostly desert region has been turned into productive agricultural land. The specimen notes of the 1955 issue

always have serial numbers beginning with the Hebrew letter aleph followed by six zeros.

The ten lirot note depicts a settlement in the

fertile Jezreel Valley in southern Galilee. This is

the only denomination of this issue to have the

serial numbers and the word Specimen

overprinted in red rather than black. The notes

with black serial numbers appeared later and

were not produced in specimen form.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

405

The fifty lirot note had a face value of about $28 at the time of its issue, and this was high

enough to restrict its circulation. Only about 1,400,000 of these notes were printed with the first

million having black serial numbers and the last 400,000 having these printed in red. The note

measures 160 x 87 mm in size and is predominantly dark blue-green in color. Much use,

however, is made of underprints in rose and yellow. The flower depicted at the upper right is an

oleander. This note was not issued until September 18, 1957 for notes with black serial numbers,

and notes with red serial numbers did not appear until May, 1960. Thus the issue of some notes

of the 1955 types overlapped to a considerable extent those with the new designs that were

introduced in 1958-60. Notes of the four lower values of the 1958 issue are identical in size

with those of the 1955 series, but for some reason that new 50 lirot note issued in 1960 was made

even larger than its series 1955 counterpart.

Some Israelis criticized the landscapes depicted on the faces of the 1955-type notes as

resembling too much typical picture postcards, but the criticism that the face designs drew was

trivial in comparison with the numerous adverse comments that were made concerning the back

sides of these notes. In her book on modern Israeli money Sylvia Haffner referred to these

designs as resembling an old fashioned gramophone, a sea shell, a snail, a starfish, and a group

of flying saucers for the 500 prutah, and 1, 5, 10, and 50 lirot notes, respectively. Usually they

are just referred to as abstract geometric designs. So far as I know, these designs were prepared

by the technical staff of Thomas de la Rue apparently without too much consultation with

officials of the Bank of Israel. .Admittedly these designs had little to do either with the nation of

Israel or with the traditions of the Jewish people. The new designs for notes that were introduced

between 1958 and 1960 combined the portraits of modern Israelis with vignettes of early Jewish

artifacts, and these proved to be far more popular than the 1955 designs as circulating notes

among most Israeli citizens. Incidentally the 1955 notes along with all other Bank of Israel notes

denominated in pounds or lirot were demonetized on March 31, 1984.

Although these notes can become expensive when in fully uncirculated condition, they

are relatively cheap when in only VF or XF. I see little point in acquiring notes of this series

when they are less than a full VF grade, since almost all serious collectors should be able to

afford attractive notes in VF or better. Naturally the fifty lirot note is the most expensive in all

grades. A note in strictly CU condition will probably sell for more than $500, but decent notes in

The old road to Jerusalem is depicted on the fifty

lirot note. The dominant color is deep blue green,

but this note also features shading in yellow and in

light red that makes the overall impression quite

attractive. The issued notes exist with both red

and black serial numbers, but all of the specimen

notes have black overprints only.

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

406

VF-XF should sell for not much more than $100 to $150. Watch out for edge tears on these large-

format items, and graffiti can also be a problem. The four lower denominations in strictly CU will

probably sell for rather more than $100 for the 500 prutoah, 1 lira, and 10 lirot notes. The five lirot is

the scarcest of this quartet, and a price nearer $200 is to be expected for one of these in CU.

Aattractive examples in VF or XF should cost quite a bit less with typical examples of the four lower

denominations costing in the $20 to $40 range.. Usually the ten lirot note is the cheapest and most

available of the set. An example in VF or somewhat better should probably not cost more than $20

or $25. Since its face value was $5.60 at a time when the note was in active circulation, clearly it

would not have been a very good idea to have held sizeable number of these in average grades from

the time when they were in active circulation given the decline in the value of money, etc.

For a truly extreme case of this we can consider two Israeli items from the 1950s. In 1949

Israel released the so-called Tabul souvenir sheet (a philatelic item), and these proved to be fairly

good as investments. In 1957 at another stamp exhibition Israel sold the so-called Tabil souvenir

sheet for one lira (or 56 cents in 1957 money). These items were way oversold, and today they can

be purchased either unused or as first day covers for about 16 cents each (in 2015 money).

Obviously this has proven to be a truly lousy investment. In 1957, however, one could also have

obtained CU packs of the 500 prutah and one lira notes of the 1955 issue for 28 cents per note for the

former issue and 56 cents for the latter. Today as singles in CU condition these notes would be

priced at about $100-125 each. Clearly either of these items would be worth many hundreds of times

the value of the 1957 souvenir sheet that was then highly touted while the banknotes were ignored.

Since there is an active market in these notes I feel that a short table that summarizes their

values should be of some interest. These prices represent fairly conservative estimates as to the

values of these notes, but they should prove useful to the collector desiring to acquire them from

auctions, at numismatic shows, or by electronic or postal sales.

F-12 VF-35 AU-50 CU-63

500 Prutah 10. 30. 55. 125.

1 Lira 10. 30. 50. 110.

5 Lirot 12. 35. 75. 200.

10 Lirot, red # 10. 25. 45. 110.

10 Lirot, black # 8. 20. 40. 100.

50 Lirot, black # 35. 90. 275. 500.

50 Lirot, red # 40. 100. 300. 600.

These estimates, of course, are in US dollars. I have leaned a bit to the conservative side, but I feel

that these notes would be fairly decent buys at these prices. Incidentally, I do not have these notes

for sale.

In addition to the regularly issued notes the 1955 banknotes are available as specimen notes.

I own a set which is a typical product of the Thomas de la Rue (TDLR) firm. Each note features the

well-known TDLR ovals on two of the corners. The word SPECIMEN also appears in boldface sans

serif capitals on both sides of each note. The notes all have serial numbers of the letter aleph

followed by six zeros. The sets themselves were individually numbered, and the notes in my set are

either no. 41 or 90. Specimen sets also exist that lack the TDLR ovals, have drilled holes, have

hollow letters in the word Specimen, etc. These specimen sets are not for the faint hearted, however,

since a typical set sells for $2000 or so. For Israeli banknote issues, specimen sets exist for the 1948,

1952, 1955, 1958-60, and 1968 issues. Of this very difficult quintet the 1955 specimen set is perhaps

the most readily obtainable. The 1948 set is especially popular, since it contains an example in

specimen form of the ultrarare 50 pound note of the Anglo-Palestine Bank, a note that is all but

impossible to obtain in regularly issued form.

Collecting Israeli banknotes by serial number blocks might become more popular if more

data were available to collectors on what blocks do exist, but the ranges of serial numbers and block

___________________________________________________________Paper Money * November/December 2015 * Whole No. 300_____________________________________________________________

407

letters do shed considerable light on what possibilities exist for these. All notes of this series were

printed in blocks of up to one million notes each, and the serial number of each note was preceded by

an initial letter of the Hebrew alphabet. One might assume that the 500 prutah or one lira notes

would have had the largest productions, in actual fact it was the ten lirot note that had the maximum

usage and that remains the most abundant note of this series today. I do not have actual production

data on the numbers of notes that were issued for each denomination, but these can be estimated by

studying the serial numbers of the rather large numbers of these notes that are currently available on

the market.

For the 500 prutah and one lira notes it appears that serial number blocks with initial letters

of aleph through tsadeh were used. This would involve a total of 18 letters, and so I am assuming

that 18 million of each of these notes were issued. I haven’t seen notes with two of these initial

letters, but I don’t see any reason why they would have been skipped. For the five lirot notes it

appears that the initial letters ran from aleph through resh for a total of 20 initial letters. Thus the

printing total for this denomination was 20 million. For the ten lirot notes the initial printings had red

serial numbers, while the latter ones had black serials. Presumably all 22 possibilities (aleph through

tav) exist for notes with red serials, while the notes with black serials appear to exist with initial

letters of aleph through resh. Thus there should have been a total of 20 million of these. All of these

notes have the block letter following rather than preceding the serial number, and these always

terminate with the notation /1. Notes with black serials appear to be more abundant than those with

red serials, but probably many of the ten lirot notes with black serials were printed to replace earlier

printings of these notes that had worn out. For the 50 lirot notes the total printings were much more

limited. The first million notes all had serial numbers in black, and these were always preceded by

the letter aleph. I haven’t seen any with serial numbers exceeding 900,000, but a total printing of one

million of these would seem logical. In the later printing of these notes the serial number was in red,

and it was preceded by the letter gimmel. Judging from the highest serial number that I have seen, it

seems that the total printing of this block was about 400,000 examples.

Thus in terms both of numbers printed and in terms of face value the ten lirot note was the

largest of this issue with some 68% of the total face value of the 1955 series in that denomination.

The total face value of the entire 1955 issue was about 620 miilion lirot, a value that can be

compared with total face values of about 225 million lirot in the 1952 Bank Leumi issue and about

120 million lirot (denominated as Palestine pounds) for the 1948 Anglo-Palestinian Bank issue.

Although Series 1955 Israeli notes can be expensive when in top condition, they are certainly

not rare when in only VF or XF condition. Very few collectors attempt to collect all of the possible

serial number blocks for this issue, but this would be an interesting project to undertake. For the fifty

lirot notes, there are only two varieties, viz., the black number and the red number varieties, always

with aleph and gimmel, respectively, as their initial block letters. For all four of the lower values I